Blumenberg (novel)

Blumenberg is a novel by Sibylle Lewitscharoff that was published in Berlin in 2011. Gregor Dotzauer categorizes the work as a novel-like fantasy on theological issues. It also satirizes the intellectual climate of the 1980s.

The author dedicated the novel to Bettina Blumenberg and was encouraged to write by Claudia Schmölders - who also gives a plausible interpretation - and Uwe Wolff , among others .

content

In the vicinity of the Lübeck philosopher Professor Blumenberg , who last taught in Münster , he died in 1982/1983 and later. No one survived - except, of course, the narrator. The non-philosopher among the readers of the novel occasionally ponders one of the "remote allusions". This does not mean Sibylle Lewitscharoff's reflections and anecdotes on Epicurus , Husserl , Nietzsche , Wittgenstein , Heidegger , Ritter , Taubes and Habermas , but rather the references to Blumenberg's work, which are hardly understandable for the philosophical layperson - for example those in the chapter Questionable Engelbescheid .

In the last chapter - Inside the cave - after March 28, 1996, the anniversary of Blumenberg's death, the above-mentioned dead meet “in another world”: Käthe Mehliss, Gerhard Baur, his girlfriend Isa from Heilbronn , Richard, Hansi and der Professor himself. Blumenberg had been found dead in bed by his wife towards the end of the previous chapter ( The Lion V ).

The yellowish animal hair on the deceased's pajamas jacket should not be overlooked, as they point to a construction principle of the crime novelist Sibylle Lewitscharoff - the principle of the enigmatic advance notice of a violent death. There are two ways to distinguish in which the author lets the six protagonists out of life - first, violent death, and second, death, which we perceive as natural. First the more spectacular violence. From the last sentence of the novel follows: The professor is killed by a blow from his royal lion. In fact, Blumenberg's aging pet had shown no aggressiveness at all throughout the novel. The death of Blumenberg's student Isa must also be described with the attributes of advance notice and violence worked out above. The related crime story construct: In the seventh chapter, the identity card number of the young Elisabeth Kurz - called Isa - is communicated. Two chapters later, a truck passenger scolds the dead woman as an asshole because the cyclist near Munster just let his truck run over her. Richard Pettersen from Paderborn , also a student of the professor, has inherited and is murdered by a stab in the heart in a robbery on a long trip to South America in Manaus, Brazil . The remaining three people did not die a violent death; Hansi - actually Hansjörg Caesar Bitzer - not entirely natural. He goes into business for himself in West Berlin . After the opening of the Wall , he wanted to teach his philosophy to passers-by from the East in particular, and as a result of extraordinary excitement, after two guards simply tried to calm him down, he died in October 1991 near the Zoo train station . Gerhard Baur died in 1997 of a stroke in Zurich after successfully applying to become a philosophy professor at the ETH there. So Hansi and Gerhard die after an excessive surge of emotions. Käthe Mehliss, a conventual in Isenhagen , died of natural causes - of old age - in her bed on March 12, 1987. Käthe Mehliss is presented as an extraordinary person and, besides the professor, is the only person who has really seen the lion in the professor's company. The named students and all other people cannot see that lion. Thus irrational ground is treaded; more or less room for speculation. The “ metaphysical skeptic ” Blumenberg and the nun can be understood as elitist beings. The students - especially Isa - are overwhelmed, understand and disoriented with philosophy as practiced by the professor, the world no longer, hate parents like "Bible engineer" Richard, who broke off the writing of his dissertation. The overstrained philosophy and Blumenberg bible exegesis just claimed is not true, at least for the relatively young Gerhard Baur. So another criterion for visibility has to be found: He can see the lion who has at least entered the threshold of old age. That leaves only the professor and the nun. Since Sibylle Lewitscharoff lets the imagination of Leo stand as a miracle, one can only speculate: Because the professor, if he has had a bad day, does not see the lion either, this visibility does not only depend on the wisdom of age. A religious reader might argue that the lion represents the wise man's gaze into the eye of God . According to the latter postulate, Blumenberg's deeper look into that eye was probably fatal. And the moral of the story could be: Greenhorns shouldn't philosophize too much, and intensive philosophy can be life-threatening even for old people.

Quote

The only thing that counts among philosophers is genius: "The person who confuses himself and others is the ordinary person."

Self-testimony

March 2012, Interview with Maximilian Humpert at the Leipzig Book Fair in the review forum at literaturkritik.de : The question addressed is: What does an agnostic do with the secret main character, the lion? Although the trip to the Nile took place and the Münster professorship also existed, the novel naturally thrives on inventions. It's not about Blumenberg's family, but about the appreciation of the philosopher. So far, no Blumenberg connoisseur has accused the author of lack of understanding. (However, Birgit Recki, who herself was a student of Blumenberg, did just that in a review.) The lion is a symbol for the strongest animal and also a symbol for a strong man who remains master of his instincts.

Minor matters

Of course, the text is a more complex structure than sketched above. Below, with that complexity in mind, a few more easily understandable things are touched upon very briefly. While the river trip on the Amazon is part of the business - there are credible preparations for what bad end Richard's trip to Brazil will take - the description of Blumenberg's three-month Nile tourism in 1956 serves more to fill the pages between the two book covers.

The passages - concerning Blumenberg's Jewish mother - could be discussed controversially ; For example in the sense: Isn't Sibylle Lewitscharoff's quiet but unmistakable criticism of Hannah Arendt in a novel that revolves around the singularity of the lion in the irrational actually a little out of place?

To disciple on the marble cliffs is played and on Freud's Moses . For every reader tastes, the report refers - for the formation of citizens - quotes from Samuel Beckett and a Shakespeare - Sonnet original and naming of Thomas Mann's Joseph Roman and the name Grass , Walser and Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway ; for the kitsch lover Albert Cohen's The Beauty of the Lord and for the reader between the two extremes mentioned, Malcolm Lowry's Unter dem Vulkan . Some verses of famous poems by Goethe and Matthias Claudius have been inserted. The naming of celebrities is not sparse at all. Next to Isa's “Blumenbergstuss” there is Lacan . Listening to Goulds - his interpretation of the Goldberg Variations - is recommended for insomnia . In connection with one of the philosophy students who died violently, attention is drawn to Zurbarán's tied lamb.

As in every one of her texts, Sibylle Lewitscharoff uses a word of concern here and there; here strolling, compost colors and scrambling.

Nonchalance shimmers through the narrative tone - also a characteristic of Lewitscharoff - and the omniscient narrator, who refuses to make any further loud comments in the eighth of the 21 chapters, cannot hold back in the 15th. Similar debates finally take place third in Chapter 19.

reception

The reviews often culminate in exuberant praise paid to the linguistically powerful author Sibylle Lewitscharoff.

- September 10, 2011, Gregor Dotzauer in the Tagesspiegel : The lions should give me consolation . The realistic description of the somewhat sprawling journey on the Amazon River falls outside the fantastic, intellectual framework. The narrator, speaking three times aside, descends like a deus ex machina from the novel's sky.

- perlentaucher.de indicates meetings

- Judith von Sternburg in the Frankfurter Rundschau on September 10, 2011

- Lothar Müller in the Süddeutsche Zeitung on September 10, 2011

- Andrea Roedig in the daily newspaper from October 1, 2011

- September 13, 2011, Ijoma Mangold in Time : The Lion's Consolation. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's "Blumenberg" is a bold novel. He does not reveal his secret. The tame lion - Blumenberg's favorite symbol for creating myths and structuring metaphors - watch the professor at his monumental translation of the Bible. The theologically oriented philosopher Blumenberg had given particular thought to the miracle - the believable. So the author put the miracle lion in his office in Altenberg . Professor and student live and act side by side. Blumenberg does not even notice their violent death - just as he overlooked Isa, who loved him and almost adored him, in the first row of lecture rooms.

- September 13, 2011, Uwe Justus Wenzel in the NZZ : The lion is loose . The aftermath, ie the “ platonic ” ( allegory of the cave ) in the last chapter, has “Beckettian and Dantesque features”. It's “weird, funny” and “linguistically witty”.

- September 25, 2011, Marius Fränzel at vigilie.de: Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Blumenberg . The murmuring of the philosophically tinged narrator is considered.

- September 27, 2011, Wolfgang Schneider on Deutschlandradio Kultur : Philosopher with a paw . It is only in the realm of the dead that the two parties of this campus novel, the professor and his audience, who act on their own in this world, are brought together. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's inventions in her homage to Blumenberg are fitting: the professor thinks in metaphors and one appears to him in the study.

- October 5, 2011, Patrick Bahners in the FAZ : Too close can destroy everything. That happens when the constant dealing with thoughts defines the world of life: Sibylle Lewitscharoff's novel "Blumenberg" is a royal reading pleasure . In the history of its origins, humans have survived through the formation of concepts. Blumenberg imagined man's intimate enemy in the savannah , the strongest predator in the world, so intensely that in the end it appeared to him in his nocturnal study. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's merit: In her novel reality, the lion in the study appears credible. The death of the four students as a result of the professor's lectures is taken into account by the reviewer.

- October 8, 2011, Daniel Windheuser on Friday : Additional lion visits philosophers. Metaphor game. A fine bone not only for academics: Sibylle Lewitscharoff and her fantasy about Hans Blumenberg . The professor does not regard his “rationality problem” Leo as a hallucination, but as a belated honor that he takes for granted on a “mischievous meta level”. The initially somewhat surprising presence of the “community of adoring students” in the novel is briefly explained. Richard, Gerhard, Hansi and the “love-mad” Isa are fictional characters in the “humorous ensemble piece” - not only made for humanities scholars. In the punch line ending, the imagery is blown up. Or in Dotzauer's words (see above): The predator does not keep the “allegorical distance”.

- October 10, 2011, Angela Bachmair in the Augsburger Allgemeine : Sibylle Lewitscharoff. Blumenberg . In this book about the “need for consolation of man”, about the real thing in reality and about the last things, Blumenberg's life ends happily.

- October 11, 2011, Atalante: The philosopher's cuddly toy. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's consoling figure with a lion's mane . The “ mystical transformation” of the dead in the last chapter is something for esotericists .

- October 12, 2011, Joe Paul Kroll at culturmag.de: The lion's den . Carl Schmitt and Blumenberg argued about the theologian miracle during their lifetime . The portrayal of the "sense smashers" Blumenberg is missing in the novel. The worlds of the deeply unhappy student Isa - somehow also reminiscent of Patti Smith's mental structure - are haunted . The deaths of the four young Blumenbergians may have been made from an Evelyn Waugh pattern. Richard's death is reminiscent of Waugh's "A Handful of Dust" (1934). In the last chapter, the closeness to Faust is apparently . Wanted part two of the tragedy . This comedic attempt fails. Blumenberg appears as a "half-successful philosophical novel".

- October 13, 2011, Frauke Meyer-Gosau at cicero.de: This is where the lions live . Why is the text so light as a feather? Because Sibylle Lewitscharoff must have had a lion lying next to her while writing.

- October 2011, Georg Patzer at Belletristik-Couch.de . The “antics of the higher kind” is not about reality, but about “Blumenberg's thoughts on lions”. The many side stories in the novel seem pointless. The “inadequate heaviness and effort at depth” are reminiscent of Thomas Mann. However, he wrote much longer sentences. The perplexed reader closes the book (see also November 11, 2011 at literaturkritik.de : Blumenberg und seine Löwe ).

- November 1, 2011, Nadine Hemgesberg at literaturundfeuilleton : Be careful, the lion is on the loose! Much remains diffuse.

- November 4th 2011, number 4 at volltext.net: The divine lion . Presenting the difficult (meaning philosophemes ) easily - Blumenberg could not. Sibylle Lewitscharoff can do it. The numinose appears in animal form.

- November 2011, Milena G. Klipingat at goethe.de : Sibylle Lewitscharoff - true, funny and meaningful language skills . With this “modern legend of saints” Sibylle Lewitscharoff has moved “to the center of the German literary scene”.

- December 7th, 2011, Andre at rostock-heute.de: Lions and Philosophers . Conversation between the author and Lutz Hagestedt .

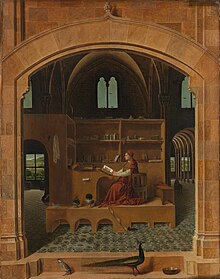

- Ralph 2011 in lesemond.de: Sibylle Lewitscharoff. Blumenberg . Antonello da Messina's painting was one of Blumenberg's favorite pictures. Some romance themes lead to key words that correspond to Blumenberg's works - work on myth (1979), realities in which we live (1981), cave exits (1989) or his concept of the “absolutism of reality”. The students soon seem like foreign bodies in the novel.

- January 26, 2012, reading and discussion with Michael Braun at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung : The Lion and the Philosopher . The lion can be understood as an attacker on realism in contemporary German literature.

- August 31, 2012, Heinz Wittenbrink: Vacation reading: Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Blumenberg . During his lifetime, Blumenberg taught his young listeners to understand something with a view to something else. Sibylle Lewitscharoff tried that too - wanted to understand Blumenberg with a view to his four unhappy students.

- October 4, 2012, Monika Costard: Hieronymus as a scholar in sermons from the Strasbourg Dominican convent of St. Nicholas in undis. With an outlook on Sibylle Lewitscharoff's novel Blumenberg (2011), in: Monika Costard / Jacob Klingner / Carmen Stange (eds.), Mertens read. Exemplary readings for Volker Mertens on his 75th birthday, Göttingen 2012, pp. 47–65.

- October 23, 2011, Denis Scheck on ARD hot off the press: Think better with lions . A Swabian praises a Swabian woman over the green clover.

- November 15, 2012, Nico Schulte-Ebbert at denkkerker.com : Colliding whiteness. Streams of thought to Lewitscharoff and Blumenberg . Isa's story is made.

- September 4, 2013 at buchpost: Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Blumenberg (2011) Blumenberg's children do not appear. There is only one mention of the wife: when she finds her night worker dead.

- March 20, 2014, Bert Rebhandl at Cargo : Blumenberg . "The lion ... ultimately means: nothing ..."

literature

First edition

- Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Blumenberg. Novel . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2011, 221 pages. ISBN 978-3-518-42244-1 (edition used).

See also

- Hans Blumenberg: Lions. With an afterword by Martin Meyer . Library Suhrkamp Vol. 1454, Berlin 2010 (1st edition), 129 pages. ISBN 978-3-518-22454-0 .

Web links

- Reading sample (up to p. 29)

Remarks

- ↑ If the Lion Miracle had been explained, the text would not deserve its subtitle Roman . Since the text of the novel is by no means unambiguous, the lion miracle can of course also be disputed: When the professor saw the animal for the first time in the nocturnal study, he immediately had seven assumptions regarding the origin (edition used, p. 12, section from 8. Zvu). All seven conjectures lead to images or stories of lions. There is absolutely no talk of a zoo or African lion. This theory of images is only thrown overboard in the very last sentence of the novel. In the last chapter, Sibylle Lewitscharoff says exactly about the nature of the subject of the Altenberg study with a mountain of flowers and a lion. The author used the “case picture by Antonello da Messina”, the one with the inconspicuous tame lion at the back right (see image above right in the article) as a template. The picture is exactly right: at heart, Blumenberg, as a world-averse researcher, is a colleague of the Bible translator Hieronymus . The withdrawn research professor knows nothing, or perhaps very little, of the death of his three students. The novel does not reflect reality, but nothing more than something like one or some of the many paintings listed in the text.

- ↑ straddle: kick.

- ↑ Krutschel - scramble: crunch.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Claudia Schmölders: Des Löwen Kern , Faustglosse on faustkultur.de

- ↑ Edition used, p. 7 and p. 219

- ↑ Edition used, p. 84, 1. Zvo and p. 157 above

- ↑ see Dotzauer discussion under Reception

- ↑ Edition used, p. 194, 5th Zvu

- ↑ Maximilian Humpert: Without the lion I would not have written 'Blumenberg'. In: literaturkritik.de. February 22, 2012, accessed January 9, 2017 .

- ↑ "The loyal reader of the philosopher will not be happy with [Lewitscharoff's] sense of mission. ... With the lion's sending, the figure of the› Blumenberg ‹experiences a trivialization which, in addition to its demonization on the motive of the miserable death of all his adepts, results in a solid cliché . A great opportunity for literature has been wasted. " Birgit Recki, "Blumenberg" or the chance of literature, in: Merkur No. 66/2012, pp. 322–328.

- ↑ Edition used, p. 152, 10th Zvu

- ↑ Blessed Longing, 3rd stanza

- ↑ Edition used, p. 216, 1. Zvo and p. 121

- ↑ Edition used, p. 109, 17. Zvo

- ↑ see for example Glenn Gould: Goldberg Variations anno 1964 YouTube (7:38 min) and anno 1955 YouTube (39:19 min)

- ↑ Gregor Dotzauer: The lions should give me consolation In: Der Tagesspiegel . September 11, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Blumenberg In: perlentaucher.de . accessed on January 9, 2017

- ^ Ijoma Mangold: The lion's consolation. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's "Blumenberg" is a bold novel. He does not reveal his secret. In: Die Zeit No. 37/2011 . September 8, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Uwe Justus Wenzel: The lion is loose In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . September 13, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ^ Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Blumenberg In: vigilie.de , September 25, 2011, accessed on January 9, 2017

- ↑ Wolfgang Schneider: Philosopher with Pranke In: Deutschlandradio Kultur . September 27, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Patrick Bahners: Too close can destroy everything. That happens when the constant dealing with thoughts defines the world of life: Sibylle Lewitscharoff's novel "Blumenberg" is a royal reading pleasure. In: FAZ . October 5, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Daniel Windheuser: Additional lion visited philosophers. Metaphor game. A fine bone not only for academics: Sibylle Lewitscharoff and her fantasy about Hans Blumenberg. In: freitag.de . October 8, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Angela Bachmair: Sibylle Lewitscharoff. Blumenberg In: Augsburger Allgemeine . October 10, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ The philosopher's cuddly toy. Sibylle Lewitscharoff's consoling figure with lion's mane In: atalantes.de . October 11, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Joe Paul Kroll: Die Höhle des Löwen In: culturmag.de . October 12, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Frauke Meyer-Gosau: The Lions Live Here In: cicero.de , October 13, 2011, accessed on January 9, 2017

- ^ Georg Patzer: Blumenberg In: belletristik-couch.de . October 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ^ Georg Patzer: Blumenberg and his lion In: literaturkritik.de . Retrieved January 9, 2017

- ↑ Nadine Hemgesberg: Be careful, the lion is loose! In: literaturundfeuilleton . November 1, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ The divine lion ( Memento from May 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: volltext.net . November 4, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Milena G. Klipingat: Sibylle Lewitscharoff - true, witty and meaningful language ability ( Memento from February 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: goethe.de . November 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Andre: Löwen und Philosophen In: Rostock-Heute.de . December 7, 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Ralph: Sibylle Lewitscharoff. Blumenberg In: lesemond.de . 2011, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Maximilian Humpert: The Lion and the philosopher In: kas.de . January 26, 2012, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Heinz Wittenbrink: Vacation reading: Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Blumenberg In: wittenbrink.net , August 31, 2012, accessed on January 9, 2017

- ↑ Denis Scheck: Think better with lions ( Memento from January 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: daserste.de . October 23, 2011, accessed January 9, 2012.

- ^ Nico Schulte-Ebbert: Colliding whiteness. Thoughts on Lewitscharoff and Blumenberg In: denkkerker.com . November 15, 2012, accessed February 15, 2019

- ^ Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Blumenberg (2011) In: buchpost.wordpress.com . September 4, 2013, accessed January 9, 2017

- ↑ Bert Rebhandl: Blumenberg In: cargo-film.de . March 20, 2014, accessed January 9, 2017