Jackdaw

| Jackdaw | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blue crested jay ( Cyanolyca cucullata ) in Costa Rica |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Cyanolyca | ||||||||||||

| Cabanis , 1851 |

The jackdaw ( Cyanolyca ) are a genus of corvids (Corvidae). They include Central and South American species that are all very similar ecologically and morphologically . Jackdaws are small to very small representatives of their family and are characterized by their deep blue body plumage and their black face mask. Their distribution area extends from southern Mexico to the central Andes . There the humid mixed and cloud forest of the tropics and subtropics forms their habitat. The food of the birds consists of arthropods , berries and sometimes eggs and small vertebrates and is looked for and picked up by them alone, in pairs or in small groups. The bowl-shaped nest is built in the branches of trees, the female incubates the clutch alone.

The genus Cyanolyca was in 1851 by Jean Cabanis set . It originated from an early radiation of the corvids in America and is the sister taxon of all other New World jays . You are currently assigned nine species, which are divided into two major lines of development. The jackdaw jays are generally regarded as sparsely researched, especially with regard to nutrition, brood, social behavior and population. The population of several species is dwindling due to the decline in their habitat; the little jay ( C. nanus ) and the white-throated jay ( C. mirabilis ) are considered threatened.

features

Physique and coloring

Jackdaws are very small corvids with a body length of 20–34 cm, a tail length of 11–17 cm, a body weight of 40–210 g and an overall very homogeneous body structure and appearance. With the little jay ( C. nanus ), the smallest living raven bird belongs to this genus. Depending on the species, the beak is stocky and short or elongated and slender. It corresponds to the basic building plan of the corvids and moves with its proportions in the middle of this family. Like all other New World jays , the jackdaw jays have a comparatively weak upper bill with a pronounced choke tooth as well as a special jaw joint that can absorb impacts better and thus supports the chiselling function of the lower bill. The expression of this characteristic varies greatly within the genus, but is overall weaker than in the derived genera of the New World Jay, such as the bush jay ( Aphelocoma ) or the blue raven ( Cyanocorax ). There are no significant differences between males and females.

The plumage of the jackdaw is characterized by a number of characteristic properties. All species have a black face mask that includes forehead, nasal bristles , eyes, cheeks, and ears. In some species it is delimited by a thin white stripe towards the vertex. The throat is colored white, black or variable shades of blue, depending on the species. The parting and the back of the head show a light turquoise to a deep, almost black dark blue. Sometimes this "cap" is clearly delimited from the darker neck and neck, sometimes it encompasses both or merges into them. The body plumage of all jackdaws is kept completely in violet, turquoise or ultramarine tones. The throat and shoulder areas are often darker than the abdominal plumage and lower back. The wing and control feathers are colored on the top in similar shades of blue to the adjacent body plumage, on the underside they have a dark, blue-black shade. The iris is dark brown or reddish brown in all species, legs and beak are always black. In young animals, the inside of the beak is partly colored pink and the colors of the plumage are duller.

Flight image and locomotion

Jackdaws move almost exclusively in the branches of trees and bushes and rarely come down to the ground. In flight, only small distances between branches or individual trees are usually overcome. The flaps of the wings are rapid, and even short phases of shaking flight have been observed in the little jay . Jackdaws usually cover shorter distances by hopping without using their wings. All species show a very lively movement pattern, which is occasionally interrupted by periods of rest to eat, to make contact calls or to look out.

Vocalizations

The jackdaw's calls are usually high-pitched and often nasal. The majority of the calls are monosyllabic, but several types also give off quick, staccato-like series of calls. For a part of the genre, the phonetic syllables wiek! and shout for alarm or communication in small groups. In this respect, the jackdaw jays are similar to the partly sympathetic bush jays, but their voice sounds softer and more melodic overall.

While the acoustic repertoire of the jackdaw - based on the Central American species - was previously considered to be comparatively small and not very complex, later studies painted a more differentiated picture. The main reason for this was a study on the vocalizations of the South American collar jay ( C. armillata ) from 1967, which revealed a multitude of different calls and combinations. Later authors came to the conclusion that the same applies to the blue-throated jay ( C. viridicyanus ).

Spreading and migrations

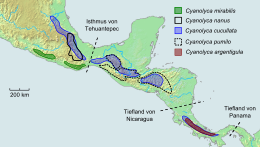

The small-scale species areas of the jackdaw are spread over the mountain ridges of Central and South America. The blue-capped jay ( C. cucullata ) advances furthest north, and its range extends from the northern Sierra Madre de Chiapas to its southeastern end and includes another, disjointed area in the Cordillera de Talamanca . The white-throated jay ( C. mirabilis ) lives in two separate areas along the southwest coast of Mexico , further to the north-west the little jay ( C. nanus ) is partly sympathetic with the blue-capped jay. The black-throated jay ( C. pumilo ) can also be found in the southeastern Sierra Madre de Chiapas together with the blue- capped jay . The same applies to the silver jay ( C. argentigula ) in the Cordillera de Talamanca.

In South America the range of the genus is limited to the Andes. The collar jay ( C. armillata ) inhabits the northern part of the mountains with the Cordillera de Mérida , the Colombian Cordillera Oriental and, separately, the Cordillera Central . The Río Cauca separates this distribution area from that of the ornamental jay ( C. pulchra ) in the Cordillera Occidental . The distribution areas of both species extend into northern Ecuador , where they overlap with that of the turquoise jay ( C. turcosa ). This penetrates south to the upper reaches of the Río Marañón , on the southwest side of which it is replaced by the blue-throated jay ( C. viridicyanus ). The species area of the blue-throated jay extends from there, interrupted by the depressions of the Río Apurímac and Lake Titicaca , southwest to about 17 ° S 67 ° W.

Closely related species live mostly allopatric and are separated from each other by climatic-topographical conditions. In the case of the Central American jackdaw jays, these are mainly the isthmus of Tehuantepec and the lowlands of Nicaragua and Panama . In South America, larger rivers and their relatively dry valleys act as barriers between the ranges of different species and populations. These today comparatively small geographical obstacles were probably decisive for speciation within the genus. Jackdaws are resident birds , but depending on the season, some species may hike at high altitude.

habitat

All species of the genus Cyanolyca are dependent on damp forests of various types. In Central America, the inhabited forests are mainly characterized by oaks ( Quercus spp.) And temperate to subtropical climates. Mixed forests of different composition are preferred here, but the blue-capped jay ( C. cucullata ) also occurs in semi-open oak parkland . In South America, tropical and subtropical deciduous forests provide the habitat .

The decisive factor for the suitability of a forest is its microclimate: dry, leeward habitats are rarely used, whereas forests with high humidity and dense epiphyte growth are preferred . Some species also seek close proximity to fresh water, such as streams, ponds or swamps. Jackdaws usually move on the edge of the forest or in the lighter secondary vegetation , less often in the dense interior of the forest.

Typical species of the forests inhabited by Cyanolyca in Central America are oaks and pines, especially sweetgum trees ( Liquidambar spp.), Tulip trees ( Liriodendron spp.), Linden trees ( Tilia spp.) And stone slabs ( Podocarpus spp.). The main species of bird here, besides the jackdaw, is the Laucharassari ( Aulacorhynchus prasinus ). In South America, typical plant species from the lower habitats include red cinchona bark trees ( Cinchona pubescens ), bamboo (Bambuseae spp.) And tree ferns . In contrast, Polylepis species dominate at higher elevations of the Andes .

Their habitat ties the genus to montane altitudes . Most jackdaws prefer altitudes between 1200 and 3000 m, only blue-capped jays and jays ( C. pulchra ) can also be found in altitudes between 800 and 1200 m. The collar jay ( C. armillata ) advances the furthest vertically at 4000 m . Where different Cyanolyca species occur sympatricly, they often move to different altitudes or occupy different areas of the same ecosystem, such as the interior of the forest and the edge of the forest.

Way of life

nutrition

Jackdaws feed primarily on insects and other invertebrates . Berries also play a role in some species. Observations of bird eggs, frogs, salamanders and lizards in the diet of some species indicate a largely opportunistic eating behavior. While other New World jays often eat nuts, these are not recorded as food for jackdaws. The Zwerghäher ( C. nanus ) feeds according to previous knowledge only of animal food; No fruit or berries were found in his stomach.

Jackdaws look for their food in different levels of the forest. Most species are moving mainly in the crown - and lower crown area of trees, but some prefer lower levels or the undergrowth . According to field observations, sympatric cyanolyca species use different areas of the common habitat when foraging for food. Jackdaws look for their food by searching the epiphyte vegetation of the tree canopy with their beak and inserting it into small openings, in order to then expand them to block the beak. This behavior, known as "circling", is typical of corvids. Plant galls are specifically opened and the eggs or larvae inside are eaten. Swarms of ants are also used as a source of food. Pieces that are too big to swallow are held in place with one foot and processed with the beak. There are differences in foraging in terms of group size. While some species always look for food individually or in pairs, others form small groups or join mixed flocks of birds.

Social and territorial behavior

When compared to other corvids, jackdaws are considered to be moderately social. In field observations, Central American species did not respond to simulated alarm calls. The flocks formed by jackdaws include only a few birds. Only after the end of the breeding season can groups of up to 30 birds come together in some species. These groups then also form sleeping communities in which the individual birds sleep close to each other. Territorial behavior has not yet been observed in any species.

Reproduction and breeding

The breeding biology of the jackdaw jays is only poorly researched. For some species there are no breeding reports at all. It is unclear whether single broods or cooperative broods are the rule in the genus. Observations of more than two adult birds on a clutch suggest the latter, at least in some species. The nests of the genus are relatively simple, hemispherical constructions made of thin twigs, lichens or needles . The nests described so far had an outer diameter of 19–33 cm and are often additionally covered with soft materials. The birds place them a few meters high in tree tops or forks of branches. Both sexes take part in nest building. Observations of three adult Türkishähern who built on the same nest, put the existence of at least for this kind of breeding helpers close. The clutch of all the species examined so far consists of two to three blue-green, dark-speckled eggs, which are incubated by the female alone while the male supplies it with food. The time until the nestlings hatch is 20 days. The nestlings are then fed by both parents.

Systematics and history of development

Research history and taxonomy

The genus of the jackdaw was first described by Jean Louis Cabanis in 1851 . He published the first description in the first volume of the Museum Heineanum , an overview he wrote of the bellows collection of the civil servant Ferdinand Heine from Halberstadt in Prussia . Cabanis cited the contrast to the azure-winged magpie ( Cyanopica ) and Schopfhähern ( cyanocitta ), from whom he separated out her "stronger beak, brush-like forehead springs etc" and put them at the same time near the cyanocorax ( Cyanocorax ). As a Latin generic name he chose Cyanolyca , a combination of the Greek terms κυάνεος kyaneos , German 'blue' , and λίκος likos , German ' jackdaw ' . The German name he gave, also based on the jackdaw, was “Dohlenheher”. Type species of the genus is the collar jay ( C. armillata ). It was not named as such by Cabanis, but was only specified in retrospect by John Edward Gray in 1855 .

The blue-throated jay ( C viridicyanus ) was the first to be described in 1832, the white-throated jay ( C. mirabilis ) the last of the jackdaw species. The so far last subspecies were first described in 1951. The first comprehensive studies of the genus Cyanolyca were first carried out in the early 1960s by John William Hardy , an American ornithologist . While he was initially undecided about the relationship between the Jackdaws and the other American genera, knowledge of their vocal expressions and morphological features led him to treat the Jackdaws as a subgenus of the bush jay ( Aphelocoma ). Hardy also contributed to the knowledge of the social behavior and habitat use of several Central and South American species. Shortly thereafter, Derek Goodwin set up the first hypotheses on internal systematics , referring primarily to plumage characteristics. In 1987 Richard Zusi was able to clearly demonstrate the monophyly of the jackdaw jays and their affiliation to the New World jays on the basis of their jaw joint structure. The exact external and internal relationships of the genus were finally described in 2007 and 2009 by A. Townsend Peterson and Elisa Bonaccorso on the basis of DNA studies. Social and breeding behavior, as well as the population and diet of most species, are still considered insufficiently researched.

External system

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematics of the new world jay according to Bonaccorso and Peterson 2007. The jackdaw jays are the most original of the recent genera of this group. |

Like all purely American corvid species , the jackdaw also belong to the group of New World jays . The common ancestor of these genera probably resembled the blue star ( Cyanopica ) and reached 8-10 million years ago in the late Miocene of Asia from North America, when there was a wooded land bridge with a warm climate between the two continents. The genus Cyanolyca represents a relatively original line of development of the New World Jay and is the sister taxon of a clade that is formed by blue ravens, blue jays , naked jays ( Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus ) and bush jays. The jackdaws split off from the forerunner of this clade in Central America, specialized in high altitudes and later reached South America from there.

Internal system

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematics of the jackdaw according to Bonaccorso 2009, based on the analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. The genus is divided into a middle (dwarf jay) and a South American clade. |

The nine species of the genus Cyanolyca are divided into two major lines of development, whose origins lie in Central and South America. The two clades probably only separated after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama 3.1 million years ago. The further diversification of the two lines of development into the species existing today took place only afterwards.

The four small Central American species - the so-called "little jays" - are in turn divided into two clades: on the one hand the little jay and white-throated jay, on the other hand the black-throated jay and the great white jay. Both lines of development are separated from one another by the isthmus of Tehuantepec , a geographical barrier that was probably decisive for cladogenesis . In South America there was a radiation that resulted in a "highland clade" - collar jays, turquoise jays and blue-throated jays - along the western Andes and two lowland forms - jays and blue-capped jays - in northern South America. The ancestor of the blue-capped jay came back to Central America from South America. The division into the nine recognized species took place through the isolation of individual populations through dry river valleys, lowlands and depressions during the Pleistocene . DNA examinations indicate that the populations of the blue-throated jay ( C. viridicyanus ) separated by the Río Apurímac differ so much that both populations have species status. The population north of the river would be Cyanolyca jolyaea, a tenth species of jackdaw.

Danger

Of the nine Cyanolyca species, the little jay and the white-throated jay are considered endangered ( vulnerable ) in the opinion of BirdLife International , some Mexican ornithologists even call for both of them to be classified as endangered . The populations of both species have suffered from intensive logging in their habitats in the past . As a consequence of this habitat destruction, both the populations and the ranges of both species declined. The situation is similar, albeit less serious, with the South American jay, which is on BirdLife's early warning list ( near threatened ).

literature

- Elisa Bonaccorso, Andrew Townsend Peterson: A Multilocus Phylogeny of New World Jay Genera. In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42, 2007. doi: 10.1016 / j.ympev.2006.06.025 , pp. 467-476.

- Elisa Bonaccorso: Historical biogeography and speciation in the Neotropical highlands: Molecular Phylogenetics of the Jay Genus Cyanolyca. In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50, 2009. doi: 10.1016 / j.ympev.2008.12.012 , pp. 618-632.

- Jean Louis Cabanis: Museum Heineanum: Directory of the ornithological collection of the Oberamtmann Ferdinand Heine, on Gut St. Burchard before Halberstadt. Part I, containing the songbirds. R. Frantz, Halberstadt 1850–1851. ( Full text )

- Derek Goodwin: Crows of the World. 2nd Edition. The British Museum (Natural History) , London 1986. ISBN 0-565-00979-6 .

- John Edward Gray: Catalog of the Genera and Subgenera of Birds Contained in the British Museum. Printed by order of the Trustees, London 1855. doi: 10.5962 / bhl.title.17986 .

- John William Hardy: Studies in Behavior and Phylogeny of Certain New World Jays (Garrulinae). In: The University of Kansas Science Bulletin 42 (2), 1961. pp. 13-149. ( Full text )

- John William Hardy: Behavior, Habitat, and Relationships of Jays of the Genus Cyanolyca. In: Occasional Papers of the CC Adams Center for Ecological Studies 11, 1964. pp. 1-14.

- John William Hardy: The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyana merida. In: The Condor 69, 1967. pp. 513-521.

- John William Hardy: Habits and Habitats of Certain South American Jays. In: Communications in Science 165, 1969. pp. 1-16.

- John William Hardy: A Taxonomic Revision of the New World Jays. In: The Condor 71, 1969. pp. 360-375. ( Full text ; PDF; 1.5 MB)

- Joseph del Hoyo, Andrew Elliot, David Christie (Eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 14: Bush-shrikes To Old World Sparrows. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2009. ISBN 978-84-96553-50-7 .

- Steve Madge , Hilary Burn: Crows & Jays. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1994, ISBN 0-691-08883-7 .

- K. Winnett-Murray, G. Murray: Two Nests of Azure-hooded Jay with Notes on Nest Attendance. In: The Wilson Bulletin 100 (1), 1988. pp. 134-135.

- Alejandro Solano-Ugalde, Rene Lima, Harold F. Greeney: The Nest and Eggs of the Beautiful Jay (Cyanolyca pulchra). In: Ornitología Colombiana 10, 2010. pp. 61–64.

- Andrew C. Vallely: Foraging at Army Ant Swarms by Fifty Bird Species in the Highlandy of Costa Rica. In: Ornithologia Neotropica 12, 2001. pp. 271-275.

- Richard L. Zusi: A Feeding Adaption of the Jaw Articulation in the New World Jays (Corvidae). In: The Auk 104, 1987. pp. 665-680.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Cabanis 1851 , p. 223.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Madge & Burn 1994 , pp. 74-79.

- ↑ Zusi 1987 , pp. 669-671.

- ↑ a b c d e f g del Hoyo et al. 2009 , pp. 570-576.

- ↑ a b Hardy 1961 , p. 129.

- ↑ Hardy 1964 , pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Hardy 1967 , pp. 514-516.

- ↑ Hardy 1964 , p. 13.

- ↑ Hardy 1967 , pp. 520-521.

- ↑ a b Bonaccorso 2009 , p. 619.

- ↑ a b Bonaccorso 2009 , pp. 628-629.

- ↑ del Hoyo et al. 2009 , p. 517.

- ↑ a b Hardy 1964 , p. 9.

- ↑ a b Hardy 1969a , pp. 1-2.

- ↑ Bonaccorso 2009 , p. 629.

- ↑ Vallely 1998 , p. 274.

- ↑ Hardy 1969a , p. 2.

- ↑ Hardy 1964 , p. 11.

- ↑ Winett-Murray 1988 , p. 135.

- ↑ Solano-Ugalde et al. 2010 , p. 63.

- ↑ Gray 1855 , p. 62.

- ↑ Hardy 1969b , pp. 371-372.

- ↑ Hardy 1964 , pp. 1-14.

- ↑ Goodwin 1986 , pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Bonaccorso & Peters 2007 , pp. 467-476.

- ↑ Bonaccorso 2009 , pp. 618-632.

- ↑ Bonaccorso & Peters 2007 , p. 474.

- ↑ Bonaccorso 2009 , pp. 627-629.

- ↑ del Hoyo et al. 2009 , pp. 575-576.

Footnotes directly after a statement confirm this individual statement, footnotes directly after a punctuation mark the entire preceding sentence. Footnotes after a space refer to the entire preceding text.