Eteocreta

Eteokreter ( ancient Greek Ἐτεόκρητες Eteókrētes , 'real, true Cretans') is the name of a historically pre- Greek and possibly non- Indo-European people on the Greek Mediterranean island of Crete . The actual popular name has not been passed down as a self or as a foreign name. The language of the people, which is called Eteocretic and is counted among the Aegean languages as the presumed successor of the Minoan language , cannot be assigned to any language family to this day.

The Eteocreters were the founders or a carrier of the Minoan culture of the Bronze Age , which is why they came into being in the 2nd millennium BC Chr. After their mythical King Minos are called Minoans the Eteocretans apply accordingly as the descendants of the Minoans and. They formed even after the rule by the Mycenaeans ( Achaeans ) on Crete from around 1450 to 1400 BC. Most of the island population. As a result of the colonization of Crete by the Greek Dorians after 1100 BC In the course of the Doric migration , the Eteocretes gradually became a minority, which, however, still inhabited parts of Crete, especially in the east of the island, in the classical period up to the Hellenistic period .

Historical references

The Eteocretes are first mentioned in the late 8th century BC. Chr. In the Odyssey of Homer . You are there as an independent people in Crete in the time around 1200 BC. Listed next to the Achaeans , Kydons , Dorians and Pelasgians . In Canto 19 of the Odyssey, lines 172 to 179, it says:

|

Κρήτη τις γαῖ 'ἔστι μέσῳ ἐνὶ οἴνοπι πόντῳ, |

Crete is a land in the dark billowing seas, |

The German version of the original Greek text given here comes from Johann Heinrich Voss from the year 1781. He translates the term Ἐτεόκρητες as "native Cretans". In the translation of Thassilo von Scheffer's Odyssey from 1938, they are called "original inhabitants". Scheffer translates the passage "ἐν δ 'Ἐτεόκρητες μεγαλήτορες" as "there the prideful inhabitants".

The ancient Greek historian and geographer Strabon (around 63 BC - after 23 AD) refers in his Geôgraphiká (Γεωγραφικά) about Staphylos from Naukratis to Homer and settled the Eteocretes in the south of the island of Crete, which was already historical at his time on. He described them next to the Kydones (Κύδωνες Kýdones ) in the west as "probably indigenous", while the Dorians later immigrated to the east. At the same time, however, Strabo states that the small town of Praisos with the sanctuary of Dictaean Zeus in the east of the island belonged to the Eteocretaries. Likewise, Strabon's settlement information does not agree with the generally accepted theses about the Doric conquest of Crete during the Doric migration, according to which the Dorians settled the island from west to the center, and later also the north, displacing the Eteocretes to the east and into the interior of the island . Restricting the Eteocretes to the south is therefore questionable.

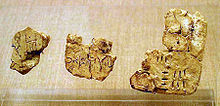

In addition to the mention by Homer and Strabo, archaeological finds provide important references to the peoples of Crete in the 2nd and 1st millennium BC. On frescoes and vases of that time there are different representations of the appearance of the island's population. Three different writing systems are known from inscriptions found before the non-written period of the dark centuries , the Cretan hieroglyphs (around 2000–1700 / 1600 BC), the linear script A (about 2000-1400 BC) and the linear script B ( around 1440–1180 BC). While the linear B script was recognized as Mycenaean Greek , the other two scripts have not yet been deciphered. The probably older Cretan hieroglyphs and the linear script A were used simultaneously for a longer period of time, while the linear script B developed from the linear script A in the Mycenaean period. The simultaneous use of the two writing systems that existed before the linear B script could indicate the existence of two peoples in a certain period of the Minoan culture, but an assignment to the Kydons or Eteocretes has so far failed due to a lack of understanding of the languages.

origin

Of the two "probably indigenous" peoples of Crete, the Kydons and Eteocretaries, the Eteocretes, as "real Cretans", seem to have been the older population of the island, otherwise the delimitation to the Kydons with the ancient authors would make no sense. Since the Eteocretes, unlike the Kydones, were still resident in the interior and east of Crete long after the Dorians had conquered them, they could also have been more populous. On the other hand, a faster assimilation of the Kydons, who are mainly native to the west, by the Dorians or a migration of the Kydons in the course of the so-called sea peoples storm is possible. But also the Eteocreters were eventually assimilated by the Doro-Greek culture.

Most of today's Cretans from Asia Minor are genetically proven. DNA analyzes of 193 islanders were compared in 2008 by Constantinos Triantafyllidis from the Aristotle University in Thessaloniki with samples from Neolithic sites. There was no match of haplotypes in the genetic material for mainland Greece , but with DNA samples from Anatolia . Mainland Greek genetic material was more like that of other areas of the Balkan Peninsula . This means that the majority of the Cretans are of non-Greek origin, neither the majority of the Mycenaeans (Achaeans) nor the Dorians. However, since today's Cretans belong to the Greek culture, an assimilation of the majority indigenous population of the island is the most likely thesis.

The cult of Cretan Zeus also points to the northeast and east, where a weather god was worshiped throughout Asia Minor and Mesopotamia , who operated under different names, but like Zeus was provided with attributes such as lightning and bull, and sometimes a helmet ( Baal ). Both as Teššup the Hurrian , whose son was represented in the form of a bull with the sun goddess Ḫepat , Šarruma , as well as Tarḫunna among the Hittites , he was the supreme god of the pantheon . With the Luwians he was called Tarḫunt and with the pre-Indo-European Hattiern Taru . While little is known about the Hattier, in whose area the Hittites later established their empire, we know about the Luwians, whose traces have been found from the south-east coast of Asia Minor via western Anatolia ( Arzawa ) to Troy , that they were in possession of hieroglyphic writing. the hieroglyphic Luwish . The Minoans also used hieroglyphic writing in the form of the Cretan hieroglyphs. Whether both forms of writing come from a common original or whether they influenced each other has not yet been researched, but they seem distantly related.

The spread of female deities also points to Anatolia as the original home of the Cretans. So there is a goddess among lions who is just as reminiscent of the Asian mother goddess Cybele as of Rhea, the mother of Zeus. The cult of the nymph Adrasteia , a daughter of the Cretan king Melissus, is also connected with her . A shield goddess recalls the archetype of the Greek Athena , whose name is of non-Greek origin. Last but not least, in Asia Minor the weather god still held the labrys , the sacred double ax often depicted in Crete, in his hands, and in Caria on the eastern Aegean coast the supreme god was once known as Zeus Labraundos .

In contrast, in relation to mainland Greece, it can be assumed that the Achaeans there were influenced by the Minoan Crete. The later Mycenaean culture has a lot in common with the Minoan culture, so the mainland Greeks adopted Minoan ceramic shapes and motifs and after a weakening of the Minoans around 1450 BC. The Mycenaean linear script B developed from the older Minoan linear script A. The cult of Diktynna , based on the nymph Britomartis , is originally Cretan and spreads from there to the mainland in the Peloponnese spread. In the opposite direction, the cult of Artemis was only brought to Crete at the time of the Doric migration.

Minoan culture

The hypothesis of the ethnic dichotomy of Crete in Minoan times is based on several indications. First of all, there are the popular names of the ancient authors, such as Homer and Strabo, where three of the five peoples mentioned can be viewed as non-Cretan. The Dorians came only after 1100 BC as a result of the Doric migration. From mainland Greece to the island. The listed Achaeans were carriers of the Mycenaean culture, which started from the Peloponnese after 1450 BC. Rule over the Minoans and probably formed only an upper class on Crete, while the Minoan culture, influenced by Mycenaeans, continued to exist in the late Minoan period. The scattered Pelasgians are also associated with mainland Greece, sometimes with Thessaly , sometimes with other parts of the country. Herodotus thinks that Pelasgia (Greek Πελασγία) is an older name for Greece and is identical to the mythical or poetic name Peloponnese .

In contrast, there are no such references to other regions with regard to Kydonen and Eteocreter. However, the actual folk names of the two population groups related to Crete are not known either. The names refer to the island's name or, in another interpretation of the Kydonen, to the city of Kydonia in the northwest of the island. Only the latter would be imprecise on the part of the ancient authors, because one would have to ask why the inhabitants of the other Cretominoic cities do not also appear as peoples of their cities, but rather were grouped together under Eteocrete. It is more likely that the city of Kydonia was named after the people of the Kydonen or their mythical king Kydon. So one can consider both the Kydones and the Eteocretes as indigenous peoples of Crete, of which the Eteocretes as "real Cretans" were probably resident on the island longer.

A second clue could be the mythical division of the island into two parts. After that, Minos , after Herodotus and Thucydides, the founder of the thalassocracy in Crete, came from the connection between Zeus and Europa . However, the mythical progenitor of the Kydonen, King Kydon, was the son of Apollo or Hermes and Akakallis , daughter of Minos. The Apollo myth of the Kydons was contrasted with the myth of the Cretan Zeus, whose cult was practiced mainly in holy places in the Psiloritis massif and in the Dikti mountains , the Zeus caves of the Idean grotto and the cave of Psychro . According to the presumed origin of Zeus from Asia Minor and based on the fact that his myth and cult was older than that of Apollo, the settlement areas in the interior of Central and Eastern Crete should be regarded as those of the older people of the island, namely the Eteocretes. There were also differences between the individual regions of Crete in the worship of local deities, such as the Kydonian Britomartis Diktynna, later regarded as the sister of Apollo.

The simultaneous use of two fundamentally different writing systems over a longer period of time in the Minoan culture, the Cretan hieroglyphs and the linear script A. Of the Cretan hieroglyphs, 137 pictograms are known can be regarded as an important indication of a two-peoples hypothesis . It is a phonetic transcription of which signs appear on early Minoan seals and which are believed to have been used ornamentally there . In addition to this script, which is possibly related to Anatolian hieroglyphic scripts, the linear script A was used.

In contrast to the Cretan hieroglyphs, which only appear on so-called seal stones, the linear A script was used more widely. Linear A consists of 70 phonetic symbols representing syllables and 100 sematographic (meaning-based) symbols that indicate sounds, concrete objects or abstract concepts. The American Semitist and Orientalist Cyrus Herzl Gordon took the view that the Minoan linear script A reproduces a Northwest Semitic dialect and brought the script into connection with Ugaritic . This corresponds to the derivation of place and name names associated with the Kydones from the Semitic language by Ernst Assmann . And Herodotus describes in his Histories in Book 5, Chapter 58, the Phoenician origin of the script via the Greek Kadmossage.

Whether the Kydons were a Semitic people living on the west and possibly the south coast of Crete, who entered into a mutual relationship with the Eteocretaries who settled in the middle and east of the island, also on the coasts there, which today is known as the “Minoan culture “Is called remains open. Evidence suggests two peoples who inhabited the island in the Bronze Age of the second millennium BC and another two, the Pelasgians and the Achaeans, who immigrated in smaller numbers at different times.

The Dorians seem to have immigrated from 1100 BC onwards. To have met far fewer people than were settled on the island in Minoan times. There are indications, as in the case of Kommos on the southwestern edge of the Messara plain on the south coast of Crete, that around 1200 BC BC coastal cities were abandoned. This is often associated with the "sea peoples storm", although devastation from that time in Crete is not documented. Today, one of the causes of the sea peoples storm is assumed to be climate change , as indicated by pollen analyzes . After defensive battles against the sea peoples in the Nile Delta , the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses III settled. Parts of these peoples in Palestine whose culture suggest an origin from the Mycenaean region, to which Crete also belonged at that time. According to Israelite tradition, the Philistines , namesake for Palestine, came from the island of Kaphtor , which is interpreted as Crete .

The Eteocreters as descendants of the Minoans also appear on Crete in the 1st millennium BC. Chr. Still in appearance and their number seems to have been significantly larger compared to the immigrant Dorians, if one proceeds from the above-mentioned genetic investigation of the origin of today's islanders. Their assimilation seems to be the rule structures after 1100 BC. Owed to BC, a period about which little is known due to the lack of written records. Only between 145 and 140 BC BC the Doric Polis Hierapytna destroyed the city of Praisos, the eteocretic center of Eastern Crete, and finally occupied the entire east of the island. What happened to the population of Praisos is not known. The Eteocretes were no longer mentioned afterwards.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Eduard Meyer : History of antiquity . First volume, 1884, p. 798 ( zeno.org ).

- ↑ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑΣ - Ὀδυσσέως καὶ Πηνελόπης ὁμιλία. τὰ νίπτρα (ancient Greek original of the 19th song of the Odyssey). gottwein.de, accessed on August 11, 2010 .

- ↑ Odyssey - Odysseus bei Penelope, washing the feet (German translation of the 19th song of the Odyssey). gottwein.de, accessed on August 11, 2010 .

- ↑ Homer : Odyssey . In: Dieterich Collection . tape 14 . Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1938, OCLC 54464155 , p. 327 (Original title: ancient Greek ἡ Ὀδύσσεια . Translated by Thassilo von Scheffer ).

- ^ Strabon , Stefan Radt : Geographika . tape 3 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-25952-2 , pp. 245 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Karl Hoeck : Crete: An attempt to illuminate the mythology and history, the religion and constitution of this island, from the oldest times to the Roman rule . First volume. Carl Eduard Rosenbusch, Göttingen 1823, p. 142 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ The Mycenaean script - The pre-alphabetical scripts in Crete and Cyprus, The Minoan scripts of Crete (and mainland Greece): Typology and Chronology. (PDF; 1.1 MB) www.uibk.ac.at, p. 8 , archived from the original on July 10, 2012 ; Retrieved September 26, 2010 .

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: Alphabet fonts. 3 The Greco-Minoan cultural symbiosis and the emergence of the “Greek” alphabet. (No longer available online.) Alpen-Adria University Klagenfurt, archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; Retrieved September 27, 2010 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Dirk Husemann: Paternity test for Pharaoh - How genetic research decodes archaeological riddles . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2143-5 , p. 105 . See also: The Minoans, DNA and all. And Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic. ( Memento of the original from March 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.7 MB).

- ^ Eduard Meyer : History of antiquity . First volume, 1884, p. 762 ( zeno.org ).

- ^ History and geography of languages and scripts - The development of scripts (Greece). www.brainworker.ch, archived from the original on January 11, 2014 ; Retrieved August 19, 2010 .

- ^ A b Ulrich Wilcken : Greek history in the context of antiquity . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-486-47690-4 , p. 41 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Konrad Schwenck , Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker : Etymologische-Mythologische Andeutungen . Büschler'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Elberfeld 1823, p. 304 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Robert Fleischer : Artemis of Ephesus and related cult statues from Anatolia and Syria . EJ Brill, Leiden 1973, ISBN 90-04-03677-6 , pp. 310 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Fritz Gschnitzer : Early Greekism: Historical and Linguistic Contributions . In: Small writings on Greek and Roman antiquity . tape 1 . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07805-3 , pp. 279 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Karl Hoeck : Crete: An attempt to shed light on the mythology and history, the religion and constitution of this island from the earliest times to the Roman rule . Second volume. Carl Eduard Rosenbusch, Göttingen 1828, p. 207 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Ivo Hajnal: The Mycenaean script - The pre-alphabetical scripts in Crete and Cyprus, The Minoan scripts of Crete (and mainland Greece): Typology and chronology. (PDF; 1.1 MB) uibk.ac.at, pp. 3–6 , archived from the original on July 10, 2012 ; Retrieved August 23, 2010 .

- ↑ Cretan hieroglyphs. www.obib.de, accessed on August 23, 2010 .

- ^ Ivo Hajnal: The Mycenaean script - The pre-alphabetical scripts in Crete and Cyprus, The Minoan scripts of Crete (and mainland Greece): Typology and chronology. (PDF; 1.1 MB) uibk.ac.at, p. 4 , archived from the original on July 10, 2012 ; Retrieved August 23, 2010 .

- ↑ Kretisch Linear A. www.obib.de, accessed on August 23, 2010 .

- ^ Gary A. Rendsburg: On Jan Best's "Decipherment" of Minoan Linear A. jewishstudies.rutgers.edu, archived from the original on March 6, 2014 ; Retrieved August 20, 2010 .

- ^ Robert R. Stieglitz: Minoan vessel names . In: Kadmos . tape 10 , issue 2, January 1971, p. 110 .

- ^ Ernst Assmann : On the prehistory of Crete . In: Philologus - Journal for Classical Antiquity . tape 67 . Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1908, p. 168 ff . ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Herodotus: Ἱστοριῶν Ε, LVIII. www.hs-augsburg.de, accessed on August 23, 2010 .

- ^ Hans Zotter: Document theory. (PDF; 446 kB) (No longer available online.) Www.uni-graz.at, p. 9 , formerly in the original ; Retrieved August 23, 2010 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Dafna Langgut, Israel Finkelstein, Thomas Litt: Climate and the Late Bronze Collapse. New Evidence from the Southern Levant. Journal of the Institute of Archeology of Tel Aviv University 40.2, 2013, pp. 149-175. online at Academia.edu

- ^ Eduard Meyer : History of antiquity . First volume, 1884, p. 803 ( zeno.org ).

- ↑ David J. Blackman: Hierapytna, later Hierapetra (Ierapetra) Greece . In: Richard Stillwell et al. a. (Ed.): The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976, ISBN 0-691-03542-3 .

- ↑ Eckart Olshausen : "We were Trojans" - Migrations in the ancient world . Ed .: Holger Sonnabend . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-515-08750-6 , pp. 99 ( books.google.de ).

Web links

- The ethnographic problems. Eteocreters and Kafti. Lycians, Tyrsenians and Philistines (Eduard Meyer: History of Antiquity, first volume )

- The Eteokreter (Kafti) and their religion (Eduard Meyer: Geschichte des Altertums, second volume )

- Praisos - The old city of the Eteocretes (PDF; 519 kB)