History of Ladakh

The history of Ladakh spans around 1100 years since the establishment of an independent kingdom. It is closely linked to the history of Tibet , which gave the region its present-day cultural character. Nevertheless, Ladakh was always exposed to influences from Central Asia and India .

Ladakh is a mountainous country in the far north of the Indian subcontinent . In the broader sense, defined from a geographical and historical point of view, it includes the area around the central upper reaches of the Indus in the western Himalayas with today's Indian districts of Leh and Kargil , the Pakistani Baltistan and the Chinese- occupied Aksai Chin . In the narrower, cultural sense, it only includes the Leh district, including Aksai Chin, which is still part of the Tibetan Buddhist culture , and the Zanskar landscape in Kargil. The following presentation focuses on Ladakh in the narrower sense.

Early history (up to 10th century AD)

Little is known about Ladakh's early history up to the mid-10th century AD. Rock carvings and archaeological finds suggest that parts of the region were inhabited by nomadic ranchers, probably from the Central Asian steppe areas, as early as the Bronze Age . Later, an Indo-European people known as "Mon" who professed Buddhism immigrated from northern India . It was displaced or assimilated by Indo-Iranian Darden in the 4th and 5th centuries AD .

There are hardly any reliable written sources for the early history of Ladakh. In Chinese , Tibetan and Arabic - Muslim chronicles there are only isolated references to the barren, dry mountainous country on the western slopes of the Himalayas . The Ladakhi chronicles only took over the historiography of neighboring states. Only from the 10th century do they offer reliable information about regional development. However, from Tibetan sources it can be seen that Ladakh was conquered by the Tibetans in the 7th century . The rising kingdom of Tibet was embroiled in bitter wars with China. Ladakh played an important strategic role in the dispute over the Chinese-dominated Turkestan , as many passes ran through it between the highlands of Tibet and northwestern Turkestan. At the time of the Tibetan conquest, Buddhism had long since gained a foothold in Ladakh, but was in part pushed back by the shamanistic - animistic Bon belief of the Tibetans.

Additional pressure on China was exerted from the early 8th century onwards by the Arabs who advanced from today's Pakistan to northern India and the then Buddhist Kashmir , which then allied with China. Baltistan in northern Ladakh became the focus of armed conflict between the Chinese, Kashmiri, Tibetans and Arabs. Chinese soldiers were temporarily stationed in the region around Gilgit , but had to surrender in 751 to the Arabs, who now spread to Turkestan. Tibet used the weakness of the Chinese to take possession of Baltistan. Ladakh's importance during this period was limited to its strategic location as a transit country. In times of peace, the sparsely populated area was largely ignored by the empires of the time, above all Tibet.

Ladakh as an independent kingdom (around 930 to 13th century)

In the 9th century, the Tibetan kingdom was in decline due to internal disputes. After the death of King Longdar in 842, it broke up into several states. Around 900 Kyi-de Nyi-ma-gön, a descendant of a branch of the old Tibetan ruling house, fled from central Tibet to the west of the country, from where he quickly expanded his sphere of influence to Ladakh , Zanskar , Lahaul and Spiti . After his death around 930, his three sons divided the empire among themselves. Ladakh, including Rutog , now in western Tibet on the border with India, became an independent kingdom under Kyi-de Nyi-ma-gön's eldest son.

Amazingly, the secession from Tibet, where Buddhism had established itself since the middle of the 8th century , was accompanied by the “Tibetanization” of culture, society and religion. Up until then, Ladakh had been subject to strong influences from the Indo-Aryan culture in northern India, which mixed with Tibetan features. With the establishment of a dynasty that traced its origins directly back to the ancient kingdom of Tibet, however, Tibetan culture prevailed. After 1000, the campaigns of the Muslim Ghaznavids in the Ganges plain caused many Indian Buddhists and Hindus to retreat to the Himalayan region, which revived the cultural exchange between Ladakh and northern India. The downright extinction of Buddhism in India by the Ghurids around 1200 put an end to Indian influence on Ladakh. In the 14th century, Ladakh finally had a completely Tibetan character. Economically, however, it remained closely tied to its main trading partner, Kashmir.

The Ladakhi chronicles give little information about the political developments of that time. They are mostly limited to the names of rulers. Only King Utpala, who ruled between 1080 and 1110, is particularly emphasized. As the first Ladakhi ruler, he significantly expanded the territory of his state. The kingdom of Nun-ti (today Kullu in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh ) had to commit to paying tribute to Utpala. Parts of western Tibet also came under his control.

Political upheavals and changing foreign rule (13th to 16th centuries)

From the middle of the 13th century until 1354, Tibet was administered by the abbots of the Sakya monasteries under Mongolian sovereignty . Nonetheless, the Mongolian influence on Tibet remained limited. From Ladakhi sources it is not clear whether Ladakh also recognized the Mongol rule. However, since the country is unlikely to have had the strength to oppose the Mongolian Great Khan , it is more than likely that it at least nominally submitted to Kublai Khan and his successors.

In the 15th century, Ladakh became the scene of significant religious upheavals. The neighboring Kashmir has been ruled by a Muslim dynasty since 1339, who conquered Baltistan in northern Ladakh in 1405 and forced its population to adopt Islam . Since then, Baltistan is no longer counted as part of the Ladakhi-Tibetan culture and thus Ladakh in the narrower sense. From central Tibet at the beginning of the 15th century the teachings of the Buddhist reformer Tsong-kha-pa , whose followers are known as Gelugpa or “yellow hats”, spread to the surrounding Buddhist empires. In the 1420s it finally reached Ladakh as well. King Trak-bum-de (reign around 1410 and 1440) accepted the rules of the new sect and had old shamanic practices, such as animal sacrifice, forbidden. However, Ladakh faced an increasing threat from its aggressive Muslim neighbor. Under Zain-ul-Abidin (ruled 1420 to 1470) Kashmir undertook at least two campaigns against Ladakh and the western Tibetan state of Guge . After they had submitted to the nominal sovereignty of Kashmir, the troops withdrew.

Around 1470, immediately after Zain-ul-Abidin's death, Lha-chen Bha-gan, a prince from a branch line of the Ladakhi ruling house, deposed the rightful king Lo-trö-chok-den. Lha-chen Bha-gan took advantage of the weakness of Kashmir after the death of its king to overthrow the Ladakhi puppet king and restore the independence of the Buddhist empire. He took the name Nam-gyal ("the victorious"), which was carried over to the dynasty he founded. Another attempt to subjugate Kashmir about ten years later failed.

Towards the end of the 15th century, Turkestan troops under Mongol command advanced from Kashgar in Central Asia to Baltistan. At first there were occasional raids against Ladakh, but in 1517 an army led by Khan Mir Mazid invaded, which was subject to King Tra-shi Nam-gyal. A new invasion under Khan Abu Sayed Mirza in September 1532 was unable to counter Ladakh. Tra-shi Nam-gyal had to bow to Kashgaria . The new masters only succeeded with difficulty in suppressing an uprising in the following year. Tra-shi Nam-gyal was executed and his nephew Tshe-wang Nam-gyal (r. 1533-1575) was elevated to the throne. The Mongol conquerors' undoing was a campaign to Tibet in 1533/34, on which the Khan died. His successor Mirza Haider retired to Badakhshan in what is now Afghanistan . In alliance with the north Indian mogul Babur , however, he soon returned to Kashmir and in 1548 again subjugated Baltistan and Ladakh. Both areas were placed under the administration of Muslim governors. In 1551 Shiite rebels murdered Mirza Haider. The restored but weak Kashmiri kingdom was unable to hold Ladakh.

From the 1550s, Ladakh recovered quickly. After it had withstood the changing foreign rule, it felt strong enough to expand to Baltistan and western Tibet itself, which it succeeded. King Tshe-wang Nam-gyal died in 1575 without leaving a son. The succession dispute between his two younger brothers weakened the empire. His vassals regained their independence. Jam-wang Nam-gyal finally emerged victorious from the controversy for the throne. While trying to restore Ladakh's position of power, he was captured by the troops of Ali Mir Khan, ruler on the throne of Muslim Baltistan. The following invasion brought a wave of sectarian violence against the Buddhist residents of Ladakh. Monasteries were destroyed and religious writings destroyed. Jam-wang Nam-gyal had to marry Ali Mir Khan's daughter, and his Buddhist wife's sons were exiled to central Tibet. Until his death around 1595, his empire was under the control of Baltistan. Nevertheless, the attempted Islamization failed, not least thanks to the efforts of Jam-wang Nam-gyal to rebuild the devastated monasteries.

Threat from the Mughals (17th century)

Under King Sen-ge Nam-gyal (reign from around 1595 to 1645) Ladakh experienced a new heyday, to which two main factors contributed: on the one hand the collapse of Baltistan and on the other hand the weakened central power of Tibet as a result of the dispute between " yellow hats " and " Red hats ”. After a long war against Guge, the eastern neighboring empire was captured. At the same time, Ladakh emerged with the Indian Mughal Empire - in possession of the Kashmir Valley since 1586 - a new enemy. The Mughals viewed the Himalayas as the natural border of their empire and therefore strived to integrate all states on “their” side of the mountain range. In 1637 the Mughal Empire installed a puppet king in Baltistan. Sen-ge Nam-gyal feared that his country could also be incorporated into the new rival. In 1639 he moved with his army to Purig, the area around today's Kargil , and finally to Baltistan, where he was defeated. However, the Mughal Empire refrained from taking possession of Ladakh on condition that it surrendered to Purig. In addition, Ladakh undertook to pay tribute, which it did not meet. Despite the unfavorable outcome for Ladakh, the war stabilized the western border of the empire, so that Sen-ge Nam-gyal could now turn to the east, where Tibet was at war with the Mongols. By 1641 he extended his domain to the Mayum Pass south of Mount Kailash . With Sen-ge Nam-gyal's death around 1645, Ladakh's expansion efforts were ended for the time being.

After Ladakh had promised in 1639 and again in 1663 to pay tributes to the Mughals without ever obeying, Grand Mughal Aurangzeb called on the Ladakhi king in 1664 to recognize the suzerainty of the Mughal empire and to promote the spread of Islam. Ladakh only bowed to this request until Aurangzeb's attention from 1672 onwards turned to the Pashtun uprisings on the north-western border. In the following two years, King De-den Nam-gyal (ruled around 1645 to 1675) conquered Purig and the lower valley of the Shyok River.

In the meantime, the power of the 5th Dalai Lama , who from 1680 claimed Ladakh for his empire, consolidated in Tibet . The chronicles of the two sides give different reasons for the conflict. According to Ladakhi scripts, it can be traced back to Ladakh's support of a red hat lama in Bhutan , whereas Tibet accused Ladakh of persecuting the yellow hats in their own country. In 1681 the war broke out. The Ladakhi capital Leh soon fell, and King De-lek Nam-gyal (reigned around 1675 to 1705) asked the Mughal Empire for help. This immediately agreed, defeated the Tibetans in 1683 and now demanded the price for his assistance, including biennial tribute payments and territorial cedings to allies of the Mughals. De-lek Nam-gyal was forced to accept Islam and from then on called himself Aqabut Mahmud. Above all, however, all Ladakhi coins had to be minted in the name of the Mughal emperor, so Ladakh actually became a vassal of the Mughals. In addition, in the Treaty of Tingmosgang 1684, it had to cede some possessions to Tibet. For Ladakh's economy, on the other hand, the new situation turned out to be quite advantageous, as it received certain trade privileges, especially in the wool trade between Tibet and the Mughals-administered Kashmir. This mediating role certainly contributed to Ladakh being able to maintain its independence at all.

Ladakh until the Dogra conquest (18th century to 1834)

As long as the Mughal Empire dominated North India politically and militarily, maintaining Ladakhi independence was a real balancing act. The decline of the Mughal power after Aurangzeb's death in 1707 meant a considerable relief in foreign policy. On the other hand, Ladakh was unable to strengthen its own position of power in the 18th century due to weak rulers; it owed its independence rather to the weakness of its opponents. However, new adversaries soon emerged from the power vacuum that had developed in India.

In the 18th century, the Mughal Empire came under increasing pressure from attacks by the British East India Company , the Marathas and the Pashtuns . The latter took Kashmir in 1751 under Ahmad Shah Durrani . Ladakh now had to pay its tributes to the rulers of the Durrani family . His religious and trade relations with Tibet, which had been subject to the Chinese Qing emperors since 1720 , were not affected by this, nor was his status as an independent kingdom. A dispute about the succession weakened the Pashtuns from around 1800. Their rule lasted until 1819, when Kashmir was incorporated into the Punjab , which was united by the Sikh Ranjit Singh . In order to defend itself against its expansionist efforts, Ladakh asked the British for support. An envoy from the British East India Company, William Moorcroft , negotiated an agreement in 1820/21, which the company refused to avoid entanglement with the Punjab. This in turn strengthened the Punjab in its plan to conquer Ladakh. However, Ladakh rejected demands for tribute and recognition of Ranjit Singh's sovereignty. At first it was able to hold its own, as its new adversary was involved in several wars.

Above all, the Hindu Dogra in Jammu under Gulab Singh , a subordinate of the Punjab, showed an increasing interest in the strategically important Ladakh. Gulab Singh had voluntarily submitted to the emerging Sikh empire in order to be able to continue the rule of his family. In 1822 Ranjit Singh appointed him Hereditary King ( Raja ) of Jammu. Gulab Singh took advantage of Ladakh's internal disputes by supporting opponents of the king. Neither the Punjab nor the British opposed the rise of the Dogra, the former because it could not do without its strongest subordinate, the latter because they saw the rise of the Dogra as the dawning of an internal conflict in Punjab, their only remaining serious rival in India . The British focus was particularly on the lucrative wool trade with Tibet, which was carried out via Ladakh. Ladakh had become nothing more than a plaything for greater powers.

Under these circumstances, Gulab Singh sent his most capable general, Zorawar Singh , with 4000 soldiers to Ladakh in 1834 , which was unable to defend itself against the overwhelming odds . A request for help to the British went unanswered. Ultimately, King Tshe-pal Nam-gyal had to surrender. He undertook to make reparation of 50,000 rupees and annual dues of 20,000 rupees. The independence of Ladakh ended after around 900 years with the conquest by the Dogra.

Under the Dogra Rajas (1834 to 1947)

During the first years of Dogra's rule in Ladakh , Zorawar Singh faced repeated local uprisings. Several times the Ladakhi king was replaced by a new puppet ruler. Some of the uprisings were fueled by the Punjab governor in Kashmir, who was not satisfied with the decline in wool imports from Tibet due to the invasion. Ranjit Singh, however, fully recognized the conquest. In 1839 Zorawar Singh also took Baltistan. Ranjit Singh died in the same year, but the Punjab still seemed too powerful to attack the Kashmir Valley. Instead, Tibet came into focus. Access to the highlands was made possible by the incorporation of Ladakh.

In order to bring the wool trade completely under his control, Gulab Singh wanted to revive Ladakh's old territorial claims on Western Tibet, the country of origin of the wool exported to Kashmir through Ladakh. In 1841 the conditions for an attack on Tibet seemed favorable given the weakness of the surrounding powers: the Sikh empire was in decline after Ranjit Singh's death, while the British engaged in two wars against Afghanistan ( First Anglo-Afghan War ) and China ( First Opium War ) were involved, plus riots in Burma . Tibet itself was weakened by the power struggle between the 11th Dalai Lama's guardian and his ministers. In the summer of 1841 General Zorawar Singh set out from Ladakh with 4,000 soldiers, many of them Ladakhi, for Tibet. The aim was to regain the territory west of the Mayum Pass, which belonged to Ladakh around 200 years earlier, to the Nepalese north-western border . The campaign caused great annoyance among the British because it ran counter to their strategic and economic interests. They gave the Punjab an ultimatum to withdraw the troops of his Dogra subordinate to Ladakh by December 10, 1841. The Dogra resisted a retreat until their army was defeated on December 14th and lost their leader, Zorawar Singh. By March 1842, the pre-war status had been restored.

Among the prisoners the Tibetans took was the head of the Hemis Monastery in Ladakh, Goen-po. The defeat of the Dogra awakened in him the hope of being able to free his homeland from foreign rule. In a secret letter to Ladakh he reported on the death of Zorawar Singh and called for an uprising against the Dogra. A new king was proclaimed in Leh. At the same time, Gön-po asked the British for help, but without success.

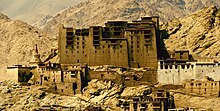

Meanwhile, Tibetan ministers had sent a petition to the Chinese emperor on behalf of Ladakh and Baltistan. Through this intrigue, Tibet hoped to annex Ladakh. In June 1842 around 5,000 Tibetan soldiers made their way to Ladakh. Gulab Singh was warned to evacuate Ladakh. As compensation, he was promised delivery of wool, cloth and tea. Gulab Singh refused. In alliance with the ruler of Baltistan, deposed by the Dogra, the Tibetan troops soon besieged the Ladakhi capital Leh. When they heard of the approaching relief troops, they withdrew into the upper Indus valley until their own reinforcements arrived from Tibet. At Chushul there was a battle with a victorious outcome for the army of Gulab Singh, which shortly afterwards dammed the river, flooded the Tibetan camp and thus forced its opponent to surrender. As a result of the war, Tibet recognized Dogra rule over Ladakh. In return, the Dogra had to forego all further territorial claims. Ladakh's royal family was allowed to stay in Ladakh as long as they did not rebel against the Dogra, but had to move from the royal palace in Leh to the village of Stok. Trade with western Tibet continued, so there was no negative impact on Ladakh's economy.

Ladakh thus finally had to submit to Gulab Singh, the Dogra-Raja of Jammu , who in turn was subordinate to the Punjab. However, after the death of the Punjab ruler Ranjit Singh in 1839, the collapse of his state seemed only a matter of time. In 1845 Gulab Singh refused to continue serving the Punjab as a feudal man. A year later, the Punjab had to recognize the full independence of Jammu, mainly under pressure from the British East India Company . The Kashmir Valley passed into British ownership, but was then sold to Gulab Singh, who was able to realize his long-cherished dream of an independent Dogra kingdom in Kashmir. Relations with the company were formalized in the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846 . Even if Kashmir was able to secure a fairly high degree of internal independence compared to other Indian princely states , from then on it was de facto part of the British sphere of influence.

From the 1860s onwards, Kashmir and Ladakh came again more strongly into the focus of the imperialist great power politics of the British, especially with regard to the dispute with Russia over the supremacy in Central Asia , known as The Great Game . While the British continued to expand into northwest India, the Russian Empire expanded into western Turkestan . When the Chinese Empire lost control of its northwesternmost province, Xinjiang, to the Central Asian warlord Jakub Bek in 1865 , both Russia and British India tried to expand trade relations with Jakub Beck's empire. The British envisaged a road from northern India through Ladakh to East Turkestan. To this end, they signed a treaty with the Maharaja of Kashmir in 1870 . Trade with East Turkestan brought little profit, however, and in 1877 the area again fell to China.

The competition between the British and the Russians came to a head in the 1880s when Russia established contacts with the local ruler of the small state of Hunza , which was subordinate to Kashmir . As the Kashmiri Maharaja was unable to cope with the border conflict, he was ousted in 1889 and only reinstated in 1921. Meanwhile, the British had increased their diplomatic and military activities in the region. They set up a representation in Gilgit (Baltistan), which was supposed to monitor the events in northern Kashmir and to set up a powerful protection force that was always ready for action. In 1890 a Russian delegation visited Hunza again and assured its ruler Safdar Ali support against the increasingly influential British. A year later, Safdar Ali's decision to evict Kashmiri troops from his country led to a brief but bloody war with the British, which the latter won. Neither Russia nor China came to his aid, wanting to avoid open confrontation with Britain at all costs. With the end of the war, the British had finally consolidated their position of power in Kashmir and Ladakh.

Although the Russian position was weakened with the defeat, the territorial dispute soon spread to Ladakh as well. Under pressure from the Russians, Chinese officials claimed the traditional Ladakhi Aksai Chin highlands as part of Tibet from 1896 . The uninhabited, hostile highlands mainly consist of a salt desert, the salt deposits of which were used by Ladakhi and Central Asian traders. However, since the area had no significant economic or strategic use for the British, they offered it to China in exchange for recognition of British sovereignty over Hunza. However, China did not respond to the proposed deal.

No major political or economic changes occurred in Ladakh until the 1940s. The struggle of the imperialist colonial empires and China for power and influence passed Ladakh by, especially since Tibet was able to free itself from its dominance in 1911 with the collapse of the empire in China.

In the First Indo-Pakistani War (1947/48)

In August 1947 India gained independence from Great Britain. The former British India was divided into a predominantly Muslim state called Pakistan and predominantly Hindu India . However, the princely state of Kashmir had not decided to belong to either of the two states by the time of independence. The Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh sought the independence of Kashmir. The majority of the population of his state was Muslim, so that Pakistan claimed the area for itself.

In October 1947, pro-Pakistani irregulars invaded Kashmiri territory, whereupon the Maharaja asked India for assistance. India was ready to comply with the request for help, but only on the condition that Kashmir would join India. After this was done, Indian troops intervened in the conflict, which expanded into the First Indo-Pakistani War . Within a short time, Buddhist Ladakh was occupied by Indian troops. In the spring and summer of 1948, Pakistan succeeded in advancing from Skardu in Baltistan via Kargil to the northwest of Ladakh, which was thus cut off from the Indian-occupied Kashmir Valley. Ladakhi officials who wanted to prevent their country from becoming a part of Pakistan sent a request for help to the headquarters of the Indian army in Kashmir. The Air Force immediately set up an airlift into the Ladakhi capital Leh , via which Gurkha units were flown in. They brought the Pakistani advance to a halt a few kilometers west of Leh. At the same time, an alternative, but extremely impassable, land connection was opened from Manali in what is now the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh over the almost 5000 meter high Bara Lacha Pass to Leh in order to be able to bring supplies. In November, the Indian army broke through the Pakistani defenses at the Zoji La Pass between Srinagar and Kargil. On November 23, Kargil was retaken and the Pakistani forces were pushed back from Ladakh.

The United Nations eventually negotiated a ceasefire between India and Pakistan, which went into effect on January 1, 1949. The armistice line, which to this day is not recognized by any side as an official border, divides the administrative unit of Ladakh in the north. The northern half comprises the Muslim Baltistan and has been subordinate to Pakistan since then. The southern, Buddhist part, Ladakh in the narrower sense, has been under Indian administration since then. Pakistan continues to lay claim to the Indian part of Kashmir including Ladakh.

Under Indian administration (since 1948)

Sino-India border conflict

In the 1950s, as a result of the rise of the Maoists in China , Ladakh again became the focus of power-political disputes. The expansion of Maoist rule to Xinjiang initially only had economic consequences for Ladakh: After the Chinese closed all foreign representations in Xinjiang, including the Indian consulate, in order to prevent any outside influence in the region, trade with Ladakh completely collapsed. However, the occupation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China aroused fears in India that the border issues that had not been resolved in the 19th century could flare up again. In fact, the Chinese People's Liberation Army , unnoticed by Indian authorities, crossed the disputed Aksai Chin area in northeast Ladakh when it invaded western Tibet in 1950 . With the transformation of the Indian mission in Lhasa into a consulate general and finally with an agreement in 1954, India diplomatically recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet. Thanks to the good relations between China and India in the first decade after its independence, the question of demarcation between the two countries was initially left out.

Only when China gradually expanded its sphere of influence to parts of Aksai Chin from 1956 and built a connecting road from Tibet to Xinjiang through the almost deserted highlands in 1957/58 did tensions arise between New Delhi and Beijing. The exchange of goods between Tibet and Ladakh, which had always been important, suffered increasingly from the changed political situation. For example, the Indian government prohibited the export of “strategic goods” via Ladakh to the Tibetan highlands. The bloodily suppressed Tibetan popular uprising of 1959 had further negative consequences for Ladakh. On the one hand, the arrival of Tibetan refugees aggravated the already poor economic situation; on the other hand, the mistreatment of Ladakhi monks in Tibet led to additional tensions between India and China. Border talks in 1960 failed. To counteract the occupation of Aksai Chin, India set up several border posts in the disputed area. The first military incident occurred in July 1962 when Chinese units blocked such a post for several days.

In September, the first skirmishes broke out on the north-eastern border of India, where China also made territorial claims, which escalated into the Indo-Chinese border war. In Ladakh, China occupied all of Aksai Chin as well as the previously Indian-held region around the border village of Demchok about 240 kilometers southeast of Leh during the war . Several thousand people were killed in the fighting. On November 20, China surprisingly announced a ceasefire, but retained Aksai Chin and Demchok. Although India still officially claims those areas as part of Ladakh, there have been no border incidents since 1962. Instead, both sides have since kept the status quo .

The war had a devastating economic impact on Ladakh. An Sino-India trade agreement from 1954 expired in the summer of 1962 and was not extended, so that trade in Tibet finally came to a standstill. In addition, Ladakh remained closed to foreigners as a result of the war. It was not until 1974 that it became freely accessible again, mainly to open up tourism as a new source of income for the impoverished region. In fact, tourism has now developed into an important pillar of the Ladakhi economy.

Internal development since 1948

In 1951, the year after the Indian Constitution came into force, a State Constituent Assembly was constituted in Jammu and Kashmir and the first elections were held. In 1957, India tied Jammu and Kashmir more closely into its federal system by giving it the status of a federal state with special rights. As the largest of the seven districts, Ladakh took up about half of the new state. About half of the population professed the Buddhist and the Islamic faith.

Since the Ladakhi Buddhists only represent a minority of a little more than one percent of the total population of Jammu and Kashmir, there have been fears since the annexation to India that Ladakh could become politically sidelined in the Muslim majority state. In the 1960s, a movement emerged for the first time under the lama and politician Kushak Bakula, which advocated greater autonomy. She also criticized Ladakh's disadvantage in the distribution of financial resources. In 1968 the government of Jammu and Kashmir introduced a reservation system for disadvantaged groups. Two percent of the jobs in public administration have since been reserved for the Ladakhis. A year later, the introduction of panchayats (village councils) in Ladakh was proposed for the first time and implemented that same year. In the course of a reorganization of the administrative units of the state, the Ladakh district was divided in 1979. The larger, predominantly Buddhist (around 80 percent) eastern part has since formed the Leh district , while the smaller, western part is now a separate district called Kargil . Its population is predominantly Muslim, but the Buddhist Zanskar region also belongs to Kargil.

Despite some concessions, concerns about the political and social marginalization of the Ladakhis persisted. It is significant that the government of Jammu and Kashmir did not appoint a Ladakhi minister to its cabinet for the first time until 1988. In 1980, the relocation of a diesel generator from Zanskar to Kargil sparked great resentment. Protests broke out in the neighboring Leh district, which eventually led to a general Ladakhi autonomy movement. Supporters of different political camps founded the Ladakh Action Committee . The main demands were the conversion of the areas with a Buddhist majority into an autonomous region within Jammu and Kashmir and the recognition of the Ladakhis as a Scheduled Tribe with minority rights, which was also granted in 1989. Initially, however, the government in Srinagar did not respond to the demands. Angry at this hesitant attitude, demonstrators in Ladakhis even got into violent clashes with the police in January 1982.

With the outbreak of the violent independence movement in the Muslim Kashmir Valley at the end of the 1980s, the demand put forward in the early 1950s to separate Ladakh from the alliance with Jammu and Kashmir and to place it as a union territory under the direct administration of the Indian central government came back. The Ladakhi Buddhist Association ( Ladakhi Buddhist Association , LBA) criticized the lack of political representation of Ladakh in government and administration, and above all the unjust distribution of development aid within the state as well as the cultural and educational policy of Srinagar, which, for example, made Urdu a compulsory school subject in Ladakh established, but not the native Ladakhi language , which is related to Tibetan . In addition, Kashmiri traders based in Leh, instead of Buddhist residents, benefited from the economic boom from tourism. In 1989 the LBA organized boycotts against Muslim traders and measures of civil disobedience against officials from the Kashmir Valley. In subsequent negotiations between the Indian central government, the government of Jammu and Kashmir and the LBA, the latter renounced the status of Union territory in favor of an autonomous development council based on the model of a similar institution in Darjiling, northeast India . The Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (Ladakh Autonomous Mountain Development Council , LAHDC) was finally established in 1995 as the first step on the way to greater self-determination in the Leh district. It has 30 members, 26 of whom are elected by the people of Leh and four are appointed by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. The aim of the council is to promote economic development on its own and to improve the living conditions of the population - taking into account the traditional way of life and culture. The first chairman was LBA chairman Thupstang Chhewang.

Although it had extensive powers, the LAHDC soon proved to be ineffective. Since 2000 the idea of a union territory of Ladakh has been gaining momentum again. In 2002, supporters of this idea founded the Ladakh Union Territory Front (LUTF) as a political party, which in the same year won both seats in the Leh district in the elections to the parliament of Jammu and Kashmir. In 2005 it won 24 of 26 seats in the LAHDC elections, replacing the Congress Party as the dominant political grouping of the Council. However, the Indian state is skeptical of the establishment of a Buddhist Union Territory of Ladakh, as it considers a division of its territory on a religious basis to be incompatible with its basic secular principle.

Separation of Jammu and Kashmir

On October 31, 2019, Ladakh was separated from Jammu and Kashmir as a separate union territory (without its own legislature) .

literature

- Margaret W. Fisher, Leo E. Rose, Robert A. Huttenback: Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh. Pall Mall Press, London 1963.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Announcement: New UTs of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh come into existence. In: newsonair.com. October 31, 2019, accessed November 1, 2019.

- ↑ The separation of Ladakh from the Lok Sabha was decided on August 5, 2019 , see message: Article 370 revoked Updates: Jammu & Kashmir is now a Union Territory, Lok Sabha passes bifurcation bill. In: businesstoday.in. August 6, 2019, accessed on November 1, 2019 (English, with blog transcript of the day).