Social darwinism

Social Darwinism is a sociological theory toward which a biologistic determinism as the world represents. It was very popular in the second half of the 19th century and up until the First World War . It misinterprets partial aspects of Darwinism in relation to human societies and understands their development as a result of natural selection in the “struggle for existence ”. According to Franz M. Wuketits, the different varieties of Social Darwinism agree in three key statements:

- The theory of selection is fully applicable in social, economic and moral terms and is decisive for human development.

- There is good and bad genetic material .

- Good hereditary traits should be encouraged, bad ones eradicated.

One of the things criticized about social Darwinism is the uncritical and faulty transfer of biological laws to human societies. In addition, several of his basic assumptions are not supported by Darwin's theory and are considered obsolete by modern science. This transfer of Darwin's theories, based among other things on a naturalistic fallacy , cannot necessarily be derived from Darwin's work, nor does it even remotely correspond to Darwin's view of the world and man.

Concept history

An early well-known mention of the term "social Darwinism" can be found in an 1879 article by Eduard Oscar Schmidt in Popular Science . As early as the following year, i.e. 1880, Émile Gautier used the term in an anarchist publication Le darwinisme social published in Paris . In Italy, the term was used in 1882 by Giuseppe Vadalà-Papale in his book Darwinismo naturale e darwinismo sociale . Until the 1930s the term was used only sporadically; not as a self-designation of the people classified today as social Darwinists or the currents assigned to them, but a label normally used polemically by ideological opponents.

Social Darwinism split off from evolutionism , which presupposes an inevitable higher development of human societies from the so-called primitive "indigenous peoples" to the fully developed "civilized peoples" (see also: Comparison of sociocultural models of evolution ) . The classic representatives of this direction - Herbert Spencer , Edward Tylor and Lewis Henry Morgan - assumed that human societies and biological species are subject to a gradual evolution that extends over several stages of development.

The British philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer, from whom the expression survival of the fittest comes, had anticipated natural selection as a factor of evolution and applied it to the human population as early as 1852 in A Theory of Population , but it was Darwin who expanded the principle of natural selection on the whole of biology. Unlike Darwin, for whom diversity through mutation and natural selection are the essential components of evolution, natural selection plays only a subordinate role in Spencer's context in a context characterized by evolutionary progress and Lamarckism . With respect to social Darwinism, there is great agreement with Darwin with Spencer.

The idea of evolutionary higher development can be found in Spencer ("the law of organic progress is the law of all progress") and many other social Darwinists. Darwin said at the end of his main work that “from the struggle of nature” “the creation of ever higher and more perfect beings” emerges, while at the same time selection “causes the extinction of the less improved forms”. In relation to humans, Darwin discusses the characteristics that favor marriage and procreation, and then considers the possible consequences for society:

- “If the ... cited and perhaps as yet unknown other obstacles do not restrain the reckless, vicious and otherwise inferior members of human society from multiplying faster than the better classes, the people will decline, as world history has shown often enough Has. We must remember that progress is not an immutable law. "

Spencer and Darwin borrowed the term struggle for survival from Thomas Robert Malthus . It was Spencer who popularized the term evolution , and he was the first to use the famous Survival of the Fittest . Darwin used it as a synonym for his " natural selection ".

On the positive effects of natural selection on civilized peoples, Darwin wrote in Human Descent and Sexual Selection :

“In savages, those weak in mind and body are soon eliminated, and those who remain alive usually show a state of vigorous health. On the other hand, we civilized men do everything possible to stop the process of this elimination. We build refuge for the feeble-minded, for the cripples and the sick; we pass laws for the poor and our doctors work with the greatest skill to keep everyone's life up to the last moment. (...) Through this it happens that the weaker members of civilized society also breed their species. No one who has devoted his attention to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be in the highest degree harmful to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a lack of care, or an ill-directed care, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but with the exception of the case concerning man himself, hardly any breeder is so ignorant that he allows his worst animals to be bred. "

And he adds:

“The help which we feel compelled to devote to the helpless is chiefly the result of the instinct of sympathy, which was originally acquired as part of the social instinct, but was later made more delicate and more widely spread in the manner described above. Nor could we restrain our sympathy, if it were hard pressed by reason, without degrading the noblest part of our nature. (...) We must therefore endure the undoubtedly bad effect of remaining alive and increasing the weak; but there seems to be at least one obstacle to the constant effectiveness of this moment, in the circumstance that the weaker and inferior members of society do not marry as often as the healthy; and this obstacle could be intensified quite extraordinarily, although one can hope more than expected if the weak in body and mind abstained from marriage. "

The British anthropologist and founder of cultural anthropology Edward Tylor is seen as the founder of actual social Darwinism . Tylor described how cultural change came about through natural selection . The American anthropologist and co-founder of ethnology Lewis Henry Morgan also used the term natural selection in his works .

Ludwig Gumplowicz, as a forerunner of the sociology of conflict , saw the "battle of the races" (later of the social groups) as a natural part of social life and as the driving force of history.

The usage of the term that dominates today was first introduced in the 1930s by the sociologist Talcott Parsons , and Herbert Spencer was first brought into connection with social Darwinism. According to GM Hodgson, Parsons used the term as a means of excluding all biological approaches as the basis of sociology; regardless of whether it was Lamarckism or Darwinism. It was only through Richard Hofstadter 's publication Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 , that the term was popularized and experienced explosive use. Even today, the term is often criticized for its ambiguity and contradiction. It was criticized that social Darwinism is more like Lamarckism than Darwinism, and Spencer's “social Darwinist” main work (Social Statics) appeared a few years before Darwin's “ Origin of Species ”, which is why the name component “Darwinism” is misleading and “Spencerism” is actually better be. Michael Ruse is also of the fundamental opinion that Social Darwinism owes Spencer as much or even more than Darwin. Since social Darwinist views of society have now become unpopular, there is a tendency to exaggerate this and to deny Darwin's influence altogether. Moreover, before the development of Weismann's germplasm theory and the subsequent development of Neolamarckism, the contrast between Lamarck and Darwin was not so strongly emphasized; rather, Lamarck was seen as a legitimate forerunner of Darwin. In fact, Darwin's work reveals contradicting positions on social Darwinism. Therefore Ruse comes to the conclusion that the relationship between biological Darwinism and social Darwinism is by no means clear; This also applies to the relationship between Spencer's teachings and social Darwinism. R. Bannister sees an almost complete separation between social Darwinists and Darwinists. "Real" Darwinists like Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and Thomas Henry Huxley were not social Darwinists and the social Darwinists, regardless of whether they were in the Spencer tradition or were associated with the collectivist form later referred to as reform Darwinism, were usually not real Darwinists, although the latter often saw themselves that way, but in reality ignored important parts of Darwin's theory.

Eric Goldmann coined the term “Reform Darwinism” in 1952 for collective social Darwinism, which emphasized the terms and slogans “Adaptation”, “mutual aid” and “struggle for the life of others” in contrast to “struggle for existence” and emphasized the individualistic social Darwinism H Spencer sharply refused. In contrast to the "original" Social Darwinism, which optimistically assumed a higher development of humanity, the term Reform Darwinism thus also refers to a current that was associated with Darwinism as a threat, since civilizational influences would have switched off natural selection and therefore a degeneration of the Humanity is to be expected, provided that this is not counteracted by measures such as artificial selection. An important publication of this movement was the publication Social Control published in 1901 by the sociologist EA Ross . This reform Darwinism, which is strongly linked to the eugenics movement , gained political importance in state interventionist, progressive political directions at the beginning of the 20th century.

effect

Social Darwinism as a fighting term

Social Darwinists usually associate this with a higher development towards a more valuable way of life, as in the case of Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner . A distinction can be made between social Darwinist approaches according to whether they relate to individual or collective competition. Conventional approaches to social Darwinism are combined with political conservatism, laissez-faire, imperialism and racism. Social Darwinism existed in principle in all political camps. He achieved great influence at times. Most traditional German conservatives, on the other hand, rejected Social Darwinism for religious reasons. Various, but not all, social Darwinists advocated eugenic measures, i.e. the application of human genetic findings to population and health policy with the aim of increasing the proportion of positively assessed hereditary factors and to reduce negative hereditary factors. In connection with the scientifically discredited theory of human races , social Darwinism formed a cornerstone of the ideology of National Socialism and its “ living space ” doctrine. Due to the propagated inequality and the resulting emphasis on the right of the strong, for example, social Darwinism is now a characteristic of right-wing extremism . The core of right-wing extremist ideology is articulated in the “ideology of inequality”, from which ethnic, mental and physical differences are derived from the criterion for the assignment of a lower legal and value status for certain individuals and groups.

Influence on different ideological points of view

The historian Richard Hofstadter, who established the term "social Darwinism" in its current usage with his seminal publication Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 , presented the social Darwinism of H. Spencer and William Graham Sumner as a welcome theoretical basis for laissez-faire capitalism represented by American industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie , John D. Rockefeller et al. a. was represented and was used by representatives of conservative and economically liberal currents to combat undesirable state interference in the economy.

While the individualistic social Darwinism in the tradition of Spencer found expression mainly in a laissez-faire capitalism, there were also collective social Darwinisms which saw the struggle between races and peoples as the basis of evolutionary progress (e.g. BE Haeckel). After the popularity of Spencer's social Darwinism had already declined sharply, the religiously shaped social Darwinisms of Benjamin Kidd and Henry Drummond gained in importance and were received predominantly positively, especially by religious-conservative sides, as a defense of the faith. However, there were earlier receptions by Christian theologians on the basis of Spencer's social Darwinism. For example, the Spencer admirer and theologian Henry Ward Beecher developed a Christianized social Darwinism.

According to R. Hofstadter, Darwinist thinking is said to have influenced the thinking of the early orthodox Marxists; thus K. Marx would have referred to F. Engels on Darwin's Origin of Species as the basis for the class struggle. Socialists like Keir Hardie also took Darwinist positions. There were also socialist social Darwinists like Jack London and others who made direct reference to H. Spencer and E. Haeckel.

Reading the original letters, both Marx and Engels welcome the destruction of teleology as a positive side effect of Darwin's work . Engels wrote to Marx in 1859: “Incidentally, Darwin, whom I am reading right now, is very splendid. Teleology had not yet been broken on one side, it has now happened. ” And in 1861 Marx wrote to Ferdinand Lassalle : “ Darwin's writing is very significant and suits me as a scientific basis for the historical class struggle. Of course, you have to accept the roughly English manner of development. In spite of everything inadequate, 'teleology' in natural science is not only given the fatal blow, but the rational meaning of it is empirically explained. "

Nevertheless, social Darwinism was largely rejected from the perspective of socialism and the validity of Darwinism was restricted to physiology and anatomy. Significantly more well received was the older doctrine of Lamarckism , by the inheritance of acquired characteristics, in extremo as Lysenkoism in the Soviet Union.

Only a minority considered a compatibility to be given. The social democratic social Darwinist Ludwig Woltmann , one of the most influential authors in the field of eugenics, tried to combine Ernst Haeckel's socio-political ideas with Marxism.

Eugenics and Social Darwinism

While social Darwinism was composed of a large number of different political currents in the late 19th century, there was an increasing radicalization and mixing of social Darwinist approaches with eugenics and racial theory at the beginning of the 20th century. In this respect, eugenics is seen as a "transmission belt" that linked Darwinian evolutionary theory with welfare state planning ("social engineering"). More than Darwin, however, a thought first formulated by Francis Galton played a central role, which said that natural selection was switched off under civilization conditions and that degeneration could be expected without countermeasures .

Weingart, Kroll and Bayertz write that there has been a “radical change of direction from a progressive-democratic to a reactionary-'aristocratic' interpretation of the political content of Darwin's theory through a shift in emphasis from the principle of evolution to the mechanism of selection”. This expansion of social Darwinism into a world view and its instrumentalization by the political right was neither corrected nor prevented by developments within the scientific community. On the contrary, the development of human genetics has long been associated with eugenic objectives. Correspondingly, many biologists and physicians working in this area saw the Nazis' seizure of power as an opportunity to realize their eugenic ideas.

But only a part of the eugenicists saw themselves in the tradition of Galton or Darwin. Eugenics has been discussed and applied for thousands of years with different motives, but it only seemed possible with Galton's degeneration theory, which was taken up by his cousin Darwin after some authors with certain restrictions, others deny this, a "scientific" foundation. Precisely because the degeneration as the basis of social Darwinian eugenics could not be empirically proven, "Darwin's principle of selection provided the theoretical key argument for the reinforcement of the degeneration idea". In particular, the founders of German eugenics, Schallmeyer and Ploetz, often referred to Darwin in their writings. A large part of those who preferred the term racial hygiene instead of eugenics and who belonged to the right-wing, racist wing of the eugenics movement, rejected the Darwinist theory of evolution as materialistic and an expression of a liberal age, although they are often labeled "social Darwinist" and as a motivation for racial hygiene measures they referred to pre-Darwinist racial theories , which appear to be "scientific", for example by Arthur de Gobineau , who in his four-volume experiment on the inequality of human races prophesied a degeneration, caused mainly by racial mixing.

Until Hitler came to power in 1933, the German eugenics movement was, according to the historian Sheila Faith Weiss', politically and ideologically more heterogeneous than commonly assumed and was mainly recruited from the educated middle class. Before 1933 it was not possible to identify a politically right-wing dominance, since in the ranks of the eugenicists, for example, Fritz Lenz (National Socialist pioneer), who was classified by the historian as politically conservative , but also SPD members such as Alfred Grotjahn or officials of Christian churches, how the Jesuit Hermann Muckermann , known as the “Pope of positive eugenics”, was represented. The political standpoints spanned the entire political spectrum of the Wilhelmine and Weimar periods. This contradicts the findings of the team of authors Weingart / Kroll / Bayertz, who come to the conclusion that the majority of eugenicists were "nationalistic, if not folkish, racist or National Socialist" . It is true that there would actually have been a centrist and revisionist wing within social democracy that combined Marxism and Darwinism in a simplistic way to form an evolutionist conception of history and society (“Darwino-Marxism”). According to medical historian Manfred Vasold, however, socialist eugenics remained a marginal phenomenon within the SPD.

Within the eugenicists, who were organized in the German Society for Racial Hygiene , the literature differentiates between the radical, racist Munich wing around Friedrich Lenz, Alfred Ploetz and Ernst Rüdin and a more moderate, more "progressive" Berlin wing around Alfred Grothjan, Hermann Muckermann and Hans Harmsen , who was politically closely linked to the Center Party and parts of the Social Democratic Party. The representatives of the Munich wing usually advocated forced sterilization or even euthanasia . In contrast, the focus of the Berlin wing, which often preferred to call themselves “eugenicists” rather than “racial hygienists”, was more on measures to promote the reproduction of the "normal" population and on voluntary sterilization. In the course of the seizure of power, there was an extensive exchange of personnel from the Berlin wing in favor of the Munich wing of racial hygiene.

Social Darwinism and Nazi ideology

Although Darwinism does not inevitably lead to a specific political ideology, eugenicists and racists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries typically referred to findings from the theory of evolution in order to present their claims as scientifically founded. Many biologists of this time contributed to this, who believed that they could transfer knowledge from zoology to politics in an often simplistic way. In the historical debate, according to the historian Edward Ross Dickinson, the consensus seems to be emerging that Darwinism was a “condition of possibility” for National Socialist eugenics. The Social Darwinist interpretation of history as a struggle between different races is seen as a central component of Nazi ideology.

In Germany, the zoologist Ernst Haeckel prepared the ground for social Darwinism. The sociologist Fritz Corner described him in 1975 as the father of German social Darwinism. In addition to Haeckel, the biologists and social Darwinists August Weismann and Ludwig Plate became members of the Society for Racial Hygiene , which, according to various historians, played a central role in the influence of Social Darwinist ideas on National Socialist racial hygiene . It was founded by the physician Alfred Ploetz , who, together with Wilhelm Schallmayer, is considered to be the founder of German eugenics. He spread his ideas a. a. about a breeding utopia, which in his opinion is only a representation of Darwin's theory that has been pursued to the last consequences. By 1933 this society had 1,300 members, including many scientists and doctors and some high officials of the NSDAP . According to Schmuhl, racial hygiene was based on the monistic axiom of social Darwinism, according to which social events can be explained by the Darwinian laws of development. M. Ruse, however, emphasizes that most historians today do not assume any significant contribution of Darwinism to National Socialism. According to Robert Bannister, neo-Darwinists like A. Weismann are not social Darwinists, but on the contrary sharp opponents of social Darwinists like Herbert Spencer . According to Oskar Hertwig, on the other hand, von Weismann's neo-Darwinism and the associated turning away from remnants of Lamarckian ideas and the emphasis on natural selection led to a radicalization of social Darwinism. According to Weismann's influential doctrine of the germ plasm , every individual was determined by his or her genetic material, and any hope for moral or cultural progress through changes in the social environment had to be given up. In the eugenics literature, references to Weismann increased steadily in the 1890s and after the turn of the century.

However, the essential elements of the National Socialist ideology, which also degenerated the eugenics, which was also practiced in other countries, and which violated human rights, especially in Nazi Germany, are not, as the term social Darwinism suggests, to be traced back to sources that referred to Darwinism. The racism of the National Socialists was largely shaped by Arthur de Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain . Gobineau's work on the inequality of human races was published a few years before Darwin's Origin of Species and even after Darwin's publication, Gobineau was not a follower of Darwin, but remained skeptical about Darwinism and evolution in general. HS Chamberlain vehemently rejected Darwinism as "materialistic". In the chapter “Progress and Degeneration” of his major work The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century , he denounces Darwinism as “the development mania and the pseudoscientific dogmatism of our century” and complains that “(e) in a palpably untenable system like that of Darwin ...” of “... intoxicated by his successes, exercising such tyranny that whoever did not unconditionally swear by him was to be regarded as stillborn "; He describes the struggle for existence described by John Fiske as a “summary worldview”. Overall, he uses a rhetoric regarding Darwinism that the philosopher and biologist JP Schloss compares with that of today's intelligent design movement . Chamberlain's attitude towards evolution can also be found in the National Socialist chief ideologist Alfred Rosenberg , who saw in the National Socialist movement the completion of the Lutheran Reformation, which he saw halfway through, towards a Germanic Christianity. The specific form of National Socialist racism that led to the Holocaust against the Jews, anti-Semitism , is believed to have its roots in Christian anti-Judaism , according to some historians .

Occasionally, the anti-Judaism of Martin Luther is cited as the source of the anti-Semitism of the National Socialists, for example his work On the Jews and their Lies (1543): Their demands on the princes for the treatment of the Jews (compulsory work, expropriation, prohibition of religious practice, possibly expulsion, physical and death penalties, burning of synagogues) resembled the National Socialists' program. Reference is also made to Hitler's admiration for Luther: “This includes not only the really great statesmen, but also all other great reformers. Next to Frederick the Great are Martin Luther and Richard Wagner. ”Many historians, however, distinguish traditional Christian anti-Judaism from anti-Semitism based on race theory, which only emerged in the 19th century.

In Hitler's writing Mein Kampf , the central metaphor of social Darwinism appears in the title of the book and is taken up in various places as the "struggle for existence", "struggle for life" or also as the "struggle for existence". Hitler repeatedly advocates the right of the stronger, which he disguises as the “aristocratic principle of nature”. The chapter “People and Race” first reproduces Darwin's principle of the struggle for existence and selection, and then transfers the struggle between species to the struggle between human races. Since Hitler cites no sources on principle, no explicit reference is made to Darwin; however, his knowledge of the racial hygiene and biological literature of the time becomes clear, as Fritz Lenz proudly noted later. Hitler explicitly turned against a religious “pseudo-anti-Semitism” that allowed the Jews to save business and Judaism at the same time with a “pour of water to baptize”; rather, anti-Semitism must be built on a racial basis.

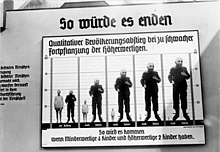

Even the official Nazi ideology was rather suspicious of the idea of human evolution, especially the idea that the Aryan master man should have had a common ancestor with the ape. Evolution was therefore fundamentally in opposition to the National Socialist way of thinking. Even among biologists, Darwin's theory was not generally accepted during the Nazi era; Thus, during the National Socialist period, the journal “Der Biologe” contained both pseudoscientific social Darwinist and anti-Darwinist treatises. The eugenic breeding ideas of National Socialism were essentially inspired by the occultist Lanz von Liebenfels , who was mainly influenced by Arthur de Gobineau. Eugenic breeding ideas do not need any evolutionary theory as a basis either, but only hereditary hypotheses; it existed long before evolution theories were developed, for example in the utopias of Thomas More and Tommaso Campanella in the 16th and 17th centuries. Nevertheless, the National Socialists repeatedly invoked biological knowledge, particularly in their eugenic policy. According to Klaus-Dietmar Henke , the “political, social, economic, psychological, intellectual and artistic processes” of social life took a back seat to “the laws of biology” in “a downright paranoid reductionism and purity mania”. The Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick said in a speech in the summer of 1933 on the basis of the law for the prevention of genetically ill offspring in relation to the welfare state: “What we have developed so far is ... excessive personal hygiene and care for the individual, regardless of the findings the doctrine of inheritance, selection of life and racial hygiene. ” The“ scientifically founded doctrine of inheritance ”would make it possible to“ clearly recognize the connections between inheritance and selection and their significance for the people and the state ”.

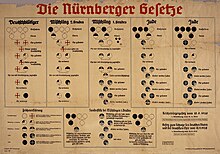

According to D. Gasman, Ernst Haeckel's social Darwinism mixed with influences from Romanticism , elements from the Germanic natural religion and anti-Semitism , which had little in common with Darwinism itself, was an essential formative element for the ideology of National Socialism and its “ living space ” doctrine. Gasman's thesis became widespread; Among other things, it was picked up by the evolutionary researcher Stephen Jay Gould . Since the political writings of the National Socialists have no direct references, Gasman can only support his theses indirectly - i.e. H. by evidence of similarities in the idea buildings of the National Socialists and Haeckels. The thesis has therefore been increasingly disputed in recent years. RJ Richards denies the similarities Gasman cited; B. Haeckel was not, as Gasman claims, an anti-Semite, but rather classified as a philosemite. Social Darwinism was used to justify imperialism and racism and led to efforts in Germany to deny the right to life in order to avoid genetic " degeneration " or " degeneracy " in order to prevent the mentally ill , the mentally handicapped or seriously hereditary . This resulted in the era of National Socialism ultimately systematic forced sterilization, for genocide , the mass " destruction of life life " or "inferior races" as the Jewish population in much of Europe. According to the Bielefeld sociologist Peter Weingart, the Sterilization Act of 1933 and the 'Nuremberg Laws' of the Hitler regime of 1935 contained all essential elements of social Darwinian breeding utopias. The reason, insofar as such a delusional attempt was made, rested on the supremacy of one ethnic group, which was regarded as natural over another, which was interpreted not as a consequence of social circumstances, but as a result of a more fundamental superiority of the more powerful group.

Social Darwinism from the perspective of science

From the perspective of evolutionary theory

In biology the view has prevailed that evolutionary processes are not always accompanied by a higher development. An objective division of all life forms into higher and lower groups is fundamentally impossible, even if this impression arises from the development of the phylogenetic history .

Supporters of social Darwinism usually give the term survival of the fittest a reinterpretation that is not covered by the biological context in which Darwin placed it. According to Darwin, the basis of biological success was not survival per se, but the production of as many viable and reproductive offspring as possible. The term survival of the fittest is often mistranslated in German: It does not mean physical fitness in the sense of physical performance, but reproductive fitness in the sense of the adaptability of a species to the prevailing environmental conditions. It also shows that both the genetic diversity rejected by social Darwinists and the existence of altruistic behaviors are widespread in nature and usually have a positive effect on the evolutionary fitness of a species. An early critic of conventional social Darwinist theories based on a theory of cooperation was the anarchist and geographer Pyotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin with his book Mutual Help in the Animal and Human World, first published in 1902 . Kropotkin already noted that Darwin did not define “the fittest” as the physically strongest or the smartest, but recognized that the stronger could be the ones who cooperate with one another. Lynn Margulis advocates a current theory of symbiotic evolution .

The attempt to explain human relationships by means of a theory based on the animal and plant world is a conclusion by analogy that is not justified without additional assumptions. Biological determinism in particular is widely rejected because social development is characterized by an interaction of genetic and cultural factors. In other words, humans can adapt by changing their genes, their culture, or a combination of both.

On the other hand, the distinction usually assumed by social Darwinists between normal conditions of “natural” selection and an artificially conditioned suppression of the selection mechanism in industrial society cannot be maintained from a scientific-descriptive point of view; Accordingly, humans are also subject to the “general biological laws” in industrial society.

From a genetics point of view

Through the chromosome theory of inheritance it was recognized that there is no fundamentally “good” or “bad” genetic material. Gregor Mendel already discovered that the individual characteristics and properties are inherited independently of one another. Against the thesis of so-called genetic degeneration through the process of civilization, Dobzhansky and Allen put forward a further argument that genetic defects or selection disadvantages are often not absolute values, but can represent either advantages or disadvantages depending on the environment. What is a disadvantage against the background of a normative conception of a “natural environment” can be permanently offset in the actual, culturally shaped environment or even bring advantages. Therefore, the easing of the selection pressure necessarily means that “bad” genes are less problematic than before. In Darwinism, “fitness” cannot be defined as anything other than relative success in reproduction. Theories of the welfare state degeneration through increased reproduction of the socially disadvantaged are in stark contradiction, which want to determine the adaptability in an absolute way and thus independently of the current environment.

Social Darwinism from the point of view of moral philosophy

From a philosophical point of view, equating a biological actual state with a moral target state is fundamentally rejected ( Hume's law , naturalistic fallacy ). In particular, the attempt to derive values for human society from nature, which can be found in the context of biologism , represents an “appeal to nature” logically seen as an irrelevant argument ( Ignoratio elenchi ), see also moralistic fallacy .

literature

- Hedwig Conrad-Martius : utopias of human breeding. Social Darwinism and its consequences. Kösel, Munich 1955, DNB 450820599 .

- Peter Weingart , Jürgen Kroll, Kurt Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes. History of eugenics and racial hygiene in Germany. (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft, 1022). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992 ISBN 3-518-28622-6 .

- Manuela Lenzen: Social Darwinism. In: Manuela Lenzen: Evolution theories in the natural and social sciences. (= Campus introductions). Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2003 ISBN 3-593-37206-1 .

- Stephan SW Müller: Theories of Social Evolution. On the plausibility of Darwinian explanations of social change. transcript-Verlag, Bielefeld 2010 ISBN 978-3-8376-1342-1 ( social theory ), (also: Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 2008).

- Hendrik Wortmann: On the desideratum of a social evolution theory. Darwinist Concepts in the Social Sciences. UVK Verlags-Gesellschaft, Konstanz 2010 ISBN 978-3-86764-264-4 ( theory and method. Social sciences ), (also: Luzern, Univ., Diss., 2009).

- Rainer Brömer: Social Darwinism. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin 2005 ISBN 3-11-015714-4 p. 1343 f.

- Georg Friedrich Nicolai : The biology of war. Considerations of a naturalist brought the Germans to their senses. 2 volumes. Introduction by Wolf W. Zuelzer . Darmstädter Blätter, Darmstadt 1983 (first Orell Füssli, Zurich 1917).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Lenzen 2003, p. 137.

- ^ AJ Mayer: Adelsmacht und Bürgerertum, 1848 to 1914 , 1986

- ↑ Peter Emil Becker: On the history of racial hygiene: ways into the third realm . Thieme Verlag 1988, p. 9.

- ^ Dieter Kreft: Dictionary of social work . Juventa Verlag 2005, p. 759.

- ↑ Franz M. Wuketits: A short cultural history of biology: Myths, Darwinism, genetic engineering. Primus, 1998, p. 115, quoted from Norbert Walz : Critical Ethics of Nature: a pathocentric-existential-philosophical contribution to the normative foundations of critical theory. Königshausen & Neumann, 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ Cf. Heinz Schott: On the biologization of humans. In: Rüdiger Vom Bruch, Brigitte Kaderas (Hrsg.): Sciences and science policy: inventory of formations, breaks and continuities in Germany in the 20th century. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Eve-Marie Engels: Charles Darwin . CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 199 f .; Franz Wuketits : Darwin and Darwinism . CH Beck, Munich 2005, pp. 93-96.

- ↑ DC Bellomy: “Social Darwinism” Revisited. In: Perspectives in American History. Vol. 1, 1984, pp. 1-129.

- ^ GM Hodgson: Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: A Contribution to the History of the Term. In: Journal of Historical Sociology. 17, 2004 (PDF)

- ↑ B. Balasz: Waiting for the new steward. Ecological anthropology and neoevolutionism. In: Acta Ethnologica Danubiana 7 (2005), pp. 23 ff., 26. ( Memento of the original from October 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ “ For as those prematurely carried off must, in the average of cases, be those in whom the power of self-preservation is the least, it unavoidably follows, that those left behind to continue the race are those in whom the power of self Preservation is the greatest - are the select of their generation ”, in: H. Spencer: A Theory of Population, Deduced from the General Law of Animal Fertility. P. 499ff.

- ^ David Weinstein: Herbert Spencer. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (Fall 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/spencer/

- ↑ the meaning that Lamarckism had for Spencer can be found e.g. B. in his essay published in 1886 "The Factors of Organic Evolution" - a defense of Lamarckism - as well as his discussion with August Weismann (David Duncan: The Life and letters of Herbert Spencer. D. Appleton & Co, New York 1908) . Through his research, Weismann had freed Darwinism from the last remaining Lamarckist ideas.

- ^ Gereon Wolters : Social Darwinism. In: Jürgen Mittelstraß (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia Philosophy and Philosophy of Science. Volume 3, 1995, p. 852.

- ^ Herbert Spencer in Progress: Its Law and Cause . 1857.

- ↑ Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species . Reclam, Stuttgart 1976 (translation of the 6th edition from 1872), p. 678 (at the end of chapter 15: summary and conclusion).

- ↑ Charles Darwin: The Descent of Man. translated by Heinrich Schmidt . Alfred Kröner, Leipzig 1908, p. 99.

- ↑ On the role of Malthus cf. G. Claeys: The "Survival of the Fittest" and the Origins of Social Darwinism. In: Journal of the History of Ideas. 61 (2000), pp. 223, 229.

- ↑ a b Catherina Diethelm: Comparison of the classical evolution theories of the 19th century by Spencer, Morgan and Tyler . (PDF; 32 kB)

- ↑ Charles Darwin: The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection . Translation by J. Victor Carus, 3rd edition. Volume 1, 1875, p. 174. online

- ↑ Cf. F. Thieme: Race theories between myth and taboo: The contribution of social science to the emergence and effect of race ideology in Germany . P. Lang, 1988, p. 58.

- ↑ Since the term, before Talcott Parsons picked it up, was mainly used by pacifist currents for their opponents, Hodgson blames the pacifism and internationalism of H. Spencer for the fact that he was never referred to as a social Darwinist until the 1930s. See GM Hodgson: Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals.

- ↑ R. Hofstadter's use of the term has already been criticized by many reviewers of his book, see RC Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 5.

- ↑ Among others, for example J. Loewenber and F. Hankins, see R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 5.

- ↑ M. Ruse: The Evolution-Creation Struggle. P. 107.

- ^ M. Ruse: The Darwinian Revolution. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1979, p. 264.

- ↑ Cf. E. Haeckel: Das Weltbild von Darwin and Lamarck; Speech for the centenary of Charles Darwin's birthday on February 12, 1909, given in the Volkshaus in Jena. [1] .

- ^ M. Ruse: The Darwinian Revolution. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1979, p. 264 f.

- ^ C. Darwin, AR Wallace, and T. Huxley collectively support the theory that nature provides no help for ethics and social policy. R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 9.

- ↑ In “Descent of man” C. Darwin deals with the theory of his cousin Francis Galton, in which he assumes an increasing tendency towards degeneration due to civilizational influences. He agrees with F. Galton that there could be degenerative mechanisms, but points out that there are several other mechanisms that counteract this (“There are, however, some checks to this downward tendency.”). For Darwin, evolution is not generally directed; There is neither a general upward development as for H. Spencer, nor an inevitable general degeneration as for the reform Darwinists in the series of F. Galton. Darwin did not support eugenics. See R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 165f.

- ^ R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 16.

- ^ E. Goldman: Rendezvous with Destiny . 1952.

- ↑ In the literature this position is reflected in the novel "The Time Machine" by the eugenics advocate and socialist HG Wells, where the class struggle flows smoothly into the race struggle. There he describes a future in which the working class and the social elite have diverged into two races, each degenerating in its own way. (See M. Ruse: The Evolution-Creation Struggle. Pp. 177-120, see also Eugenics Rides a Time Machine, HG Wells' outline of genocide by David M. Levy and Sandra J. Peart, 2002 )

- ^ R. Bannister on EA Ross and his Social Control: "Although he made only brief reference to evolution, at the heart of the theory was a perception of neo-Darwinian thas that had haunted Ross for more than a decade." R. Bannister Social Darwinism. P. 164/165.

- ^ R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 164f.

- ^ M. Ruse: Evolutionary Ethics: A Phoenix Arizen . Zygon 21 (1986), pp. 95,96.

- ^ Richard Hofstadter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. P. 85f.

- ^ NA Rupke: Review of Benjamin Kidd. Portrait of a Social Darwinist by DP Crook. In: The English Historical Review. Vol. 102, No. 403 (Apr., 1987), pp. 523-524. [2]

- ↑ Benjamin Kidd's work Social Evolution according to R. Hofstadter ( Social Darwinism in American Thought, p. 99) , published in 1894, was "the rage in the Anglo-American literary world"

- ^ Richard Weikart: The Origins of Social Darwinism in Germany, 1859-1895. In: Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. 54, No. 3 (Jul., 1993), pp. 469, 472.

- ↑ Joachim Fest: Hitler. A biography . Spiegel Verlag 2006, p. 106f.

- ↑ Ulrich Kutschera: The issue of evolution . LIT Verlag 2004, p. 270.

- ↑ Winfried Noack: The Nazi ideology . P. Lang Verlag 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Lower Saxony State Center for Political Education (ed.): Lower Saxony Lexicon . Leske and Budrich VS Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-531-14403-0 , p. 79, keyword right-wing extremism ( “Right-wing extremism can be described as an ideology of inequality, whereby inequality is to be understood in the sense of inequality. This generic term is the following Allocate ideological elements: [...] Emphasis on the right of the strong (social Darwinism) ” ).

- ↑ Werner Weidenfeld, Karl-Rudolf Korte: Handbook on German Unity, 1949–1989–1999 . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1999, p. 358.

- ^ For example, the work "Social Statics" by the social Darwinist Herbert Spencer, published in 1851, was so often cited before the US Supreme Court in order to prevent reform state intervention in the economy that Judge Holmes finally pointed out that Spencer's ideas were not part of the The US constitution is: "the fourteenth amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics" (R. Hofstadter: Socialdarwinism and American Thought. P. 46/47)

- ^ Peter Singer: A Darwinian Left . Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1999.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Gasman The Scientific Origins of National Socialism .

- ^ R. Hofstadter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. P. 99.

- ^ R. Bannister: Social darwinism, Science and Myth . P. 152.

- ^ R. Hofstadter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. Pp. 29-31.

- ↑ MJ coalter: Beecher, Henry Ward (1813-1887) . In DK McKim (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the reformed Faith . Saint Andrew Press, Louisville 1992.

- ^ R. Hofstadter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. P. 115.

- ↑ "Darwin's book is very important and serves me as a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history." from The Correspondence of Marx and Engels (New York, 1935) pp. 125-126; see also Hofstadter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. P. 115-

- ↑ M. Ruse The Evolution-Creation Struggle. P. 111.

- ↑ Joseph Sciambra: THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACK LONDON . ( Memento of the original from May 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ "As Marx had found in the struggle for existence a 'basis' for the class struggle, American socialists found even in the writings of Spencer aid and comfort for their cause" R. Hostaedter: Social Darwinism in American Thought. P 116.

- ↑ Engels to Marx, December 12, 1859, in: Karl Marx - Friedrich Engels: Briefwechsel, Vol. II: 1854-1860 . Dietz Verlag Berlin 1949, p. 548.

- ^ Marx to Lassalle, January 16, 1861, in MEW Volume 30, Dietz Verlag Berlin 1974, p. 578.

- ^ D. Gasman: Scientific Origin of National Socialism. P. 149.

- ^ Edward Ross Dickinson: Biopolitics, Fascism, Democracy: Some Reflections on Our Discourse about 'Modernity'. In: Central European History. Volume 37, No. 1 (2004), pp. 1, 3.

- ↑ R. Bannister: Social darwinsmus. P. 166.

- ↑ Weingart, Kroll and Bayertz 1992, p. 114 ff.

- ^ Weingart / Kroll / Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 20.

- ^ Weingart / Kroll / Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 381 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Walter Schmuhl : The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945 Springer Verlag, 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ Eugenic ideas can already be found, for example, in the writings of the philosophers Plato and Aristotle . In ancient Sparta , eugenics was used in the form of killing disabled newborn babies.

- ↑ z. BR Bannister: in “Descent of Man” C. Darwin deals with the theory of his cousin Francis Galton, in which the latter assumes an increasing tendency towards degeneration due to civilizational influences. He agrees with F. Galton that there could be degenerative mechanisms, but points out that there are several other mechanisms that counteract this (“There are, however, some checks to this downward tendency.”). For Darwin, evolution is not generally directed; There is neither a general upward development as for H. Spencer, nor an inevitable general degeneration as for the reform Darwinists in the series of F. Galton. Darwin did not support eugenics. See R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 165f.

- ^ Weingart / Kroll / Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes. Frankfurt am Main 1992, 75.

- ^ Weingart / Kroll / Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 38 ff.

- ↑ so the conception of the race of the right nationalist wing of the racial hygiene was criticized as pre-Darwinistic because of its static, non-evolutionary conception of race by more moderate eugenicists of the Berlin wing. See also Hans W. Schmuhl: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945. Springer Verlag, 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Sheila Faith Weiss: The Race Hygiene Movement in Germany . OSIRIS, 2nd series, 3, 1987, p. 194. [3]

-

^ Ingrid Richter: Catholicism and eugenics in the Weimar Republic and in the Third Reich: Between morality reform and racial hygiene. ISBN 3-506-79993-2 , see also book

reviews : Review by John Glad [4] , Review in The Catholic Historical Review Archived copy ( Memento of the original from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - ^ Sheila Faith Weiss: The Race Hygiene Movement in Germany . OSIRIS, 2nd series, 3, 1987, p. 194.

- ↑ Peter Weingart, Jürgen Kroll, Kurt Bayertz, “Race, Blood and Genes. History of eugenics and racial hygiene in Germany ”. Suhrkamp 1988, p. 363.

- ↑ Andreas Lüddecke: The Saller case and the racial hygiene . Tectum Verlag 1995, p. 32.

- ↑ Manfred Vasold: Socialist origins of eugenic thinking. Drain the source of madness. In: FAZ. June 7, 1996.

- ^ Hans W. Schmuhl: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945. Springer Verlag, 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Edward Ross Dickinson: Biopolitics, Fascism, Democracy: Some Reflections on Our Discourse about 'Modernity'. In: Central European History. Volume 37, No. 1 (2004), pp. 1, 9.

- ^ Hans W. Schmuhl: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945. Springer Verlag, 2008.

- ^ Edward Ross Dickinson: Biopolitics, Fascism, Democracy: Some Reflections on Our Discourse about 'Modernity'. Central European History. Volume 37, No. 1 (2004), pp. 1, 16.

- ^ Hannah Arendt: Elements and origins of total domination. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich 1991, p. 297 ff.

- ↑ An inevitability of the development is implicitly suggested in the - insofar as controversial - presentation by Richard Weikart, that is: From Darwin to Hitler. Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany . Palgrave MacMillan 2004.

- ^ Hannah Arendt: Elements and origins of total domination. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich 1991, pp. 297 ff, 300 (with further references).

- ^ Edward Ross Dickinson: Biopolitics, Fascism, Democracy: Some Reflections on Our Discourse about 'Modernity'. In: Central European History. Volume 37, No. 1 (2004), pp. 1, 18.

- ^ Geoff Eley: Introduction 1: Is There a History of the Kaiserreich? In: ders .: Society, Culture, and the State in Germany, 1870–1930. Ann Arbor 1996, p. 28.

- ^ David F. Lindenfeld: The Prevalence of Irrational Thinking in the Third Reich: Notes Toward the Reconstruction of Modern Value Rationality: Central European History. (1997), pp. 365, 371.

- ↑ Manuela Lenzen: Theories of Evolution - In the natural and social sciences . Campus, 2003, p. 138.

- ^ Andreas Frewer: Medicine and Morals in the Weimar Republic and National Socialism . Campus Verlag, 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Wolf Michael Iwand: Paradigm Political Culture . Leske and Budrich VS Verlag, 1997, p. 330.

- ↑ Jürgen Peter: The intrusion of racial hygiene in medicine. Impact of racial hygienic thinking on thought collectives and medical fields from 1918 to 1934. Mabuse-Verlag, 2004.

- ↑ Peter Weingart, Jürgen Kroll, Kurt Bayertz: Race, Blood and Genes - History of Eugenics and Racial Hygiene in Germany . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 188, 396 ff.

- ↑ Peter Weingart: Breeding utopias - wild thinking about the improvement of humans. In: Hornschuh, Tillmann et al. (Ed.): Beautiful - healthy - new world? Human genetic knowledge and its application from a philosophical, sociological and historical perspective . IWT paper; Volume / year 28, Bielefeld 2003, p. 7. (PDF)

- ↑ Michael Burleigh , Wolfgang Wippermann : The Racial State: Germany 1933-1945. Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 52.

- ↑ Hans-Walter Schmuhl: Racial hygiene, National Socialism, euthanasia: From prevention to the destruction of "life unworthy of life", 1890-1945. 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1987, p. 49.

- ↑ “How much the totalitarian philosophies of the twentieth century-Nazism, fascism, communism-owed to social Darwinism has been much debated. In the case of Hitler and his gang, historians today dilute any significant role for evolution (Darwinism in particular) and instead put much weight on the influence of cultural factors, such as the apocalyptic anti-semitism of the Volkish movement which centered around the Wagnerians at Bayreuth ”M. Ruse: The Evolution-Creation Struggle . Harvard University Press, 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ see also Friedländer: Nazi Germany and the Jews. The Years of Persecution, 1933-39. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1997.

- ^ Robert Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 1979, p. 51.

- ↑ Oscar Hertwig: To the defense of the ethical, the social, the political Darwinism . Jena 1921. [5]

- ^ Peter Weingart: "Struggle for Existence": Selection and Retention of a Metaphor, in: Sabine Maasen u. a., Biology as Society, Society as Biology: Metaphors: Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook 1994, pp. 127, 141.

- ↑ Peter Weingart: “Struggle for Existence”: Selection and Retention of a Metaphor , in: Sabine Maasen u. a., Biology as Society, Society as Biology: Metaphors: Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook 1994, pp. 127, 142.

- ↑ JP Schloss: 'The Expelled Controversy: Overcoming or Raising Walls of Division? The American Science Affiliation, Science in Christian Perspective

- ^ RJ Evans: The Emergence of Nazi ideology. In: J. Caplan (Editor): Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-927687-5 , pp. 32f.

- ↑ Houson S. Chamberlain: The Basics of the nineteenth century . Bruckmann, Munich 1912, p. 853 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ JP Schloss: 'The Expelled Controversy: Overcoming or Raising Walls of Division?

- ^ RJ Evans The Emergence of Nazi ideology. In: J. Caplan (Editor): Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-927687-5 , pp. 44-45.

- ↑ Hitler's anti-Semitism, a necessary condition for the Holocaust, was essentially shaped by his admiration for the Christian social mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, and his Christian anti-Semitism. There was also an influence of the ethnic anti-Semitism of Georg von Schönerer . See e.g. B. Joachim Fest: Hitler. A biography. Spiegel Verlag 2006.

- ^ RJ Evans: The Emergence of Nazi ideology. In: J. Caplan (Editor): Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-927687-5 , p. 32.

- ↑ see also Hitler's remark: "So I believe to act today in the spirit of the almighty Creator: 'By defending myself against the Jew, I fight for the work of the Lord." In: Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. P. 70.

- ↑ archive.org

- ^ Peter F. Wiener: Martin Luther: Hitler's Spiritual Ancestor New Jersey 1999, ISBN 1-57884-954-3 ; WM McGovern: From Luther to Hitler; the history of fascist-nazi political philosophy. Ams Pr Inc (1995) 1941, ISBN 0-404-56137-3 .

- ^ With further references Brian Vick: The Origins of the German Volk: Cultural Purity and National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Germany. In: German Studies Review. Vol. 26, No. 2 (May, 2003), pp. 241, 252.

- ↑ Felicity Rash: Metaphor in Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf. In: metaphorik.de 9/2005, pp. 74, 77. (online)

- ↑ Christian Hartmann , Thomas Vordermayer, Othmar Plöckinger, Roman Töppel (eds.): Hitler, Mein Kampf. A critical edition . Institute for Contemporary History Munich - Berlin, Munich 2016, vol. 1, p. 398.

- ^ Peter Weingart: 'Struggle for Existence': Selection and Retention of a Metaphor. In: Maasen / Mendelsson / Weingart: Biology as Society, Society as Biology: Metaphors. Kluwer, Dordrecht 1994, pp. 127, 145.

- ↑ Hitler: Mein Kampf. P. 131 .; on this Michael Mayer: NSDAP and anti-Semitism 1919–1933. March 2002, University of Munich.

- ↑ D.Gasman: The Scientific Origins of National Socialism S. 173rd

- ↑ In the occult wing of National Socialism there was z. B. a bizarre view based on the world ice theory , according to which evolution was accepted for the animal world and non-Aryans, but the Aryans had come to earth separately from spores embedded in ice crystals, where they had conquered Atlantis . John Grant, "Corrupted Science." AAPPL, ISBN 978-1-904332-73-2 , p. 258.

- ↑ "... And the monkey origin of Germans as well as everybody else could hardly be concealed. Evolution - as most of the Nazis saw it quite clearly - was fundamentally opposed to National Socialist thinking. "M. Ruse," The Evolution Creation struggle, "114.

- ↑ John Grant, "Corrupted Science." AAPPL, p. 262.

- ^ R. Bannister: Social Darwinism, Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. P. 164f.

- ↑ Alban Knecht: Eugenic Utopias of Fiction (PDF; 467 kB)

- ↑ Klaus-Dietmar Henke: “Ideas of inequality as a pacemaker of Nazi 'euthanasia'”, Scientific Journal of the Technical University of Dresden , 57 (2008), p. 54.

- ^ Wilhelm Frick: Speech at the first meeting of the Advisory Council on Population and Race Policy on June 28, 1933

- ^ D. Gasman: The Scientific Origins of National Socialism . 1971.

- ^ "For all his fame as a zoologist, however, and as a scientific worker, the Darwinism which Haeckel urged was more akin to religion than to science. Although he considered himself to be a close follower of Darwin and, as we have seen, invoked Darwin's name in support of his own ideas and theories, there was, in fact, little similarity between them. Haeckel himself openly thought of evolution and science as the domain of religion and his work was wholly foreign to the spirit of Darwin. " D. Gasman: The Scientific Origins of National Socialism . 1971, pp. 10/11.

- ^ Robert J. Richards: Myth: That Darwin and Haeckel were Complicit in Nazi Biology. In: Ronald L. Numbers (Ed.): Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2009. (PDF)

- ^ Cf. P. Hoff, MM Weber: Social Darwinism and Psychiatry in National Socialism. In: The neurologist. 73 (2002), pp. 1017-1018.

- ↑ Peter Weingart: Breeding utopias - wild thinking about the improvement of humans. In: Hornschuh, Tillmann et al. (Ed.): Beautiful - healthy - new world? Human genetic knowledge and its application from a philosophical, sociological and historical perspective . IWT paper; Volume / year 28, Bielefeld 2003, p. 10. (PDF)

- ^ SJ Gould: Illusion Progress. The many ways of evolution. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1998.

- ↑ Bernd Gräfrath : Evolutionary Ethics ?: Philosophical Programs, Problems and Perspectives of Sociobiology . Walter de Gruyter, 1997, p. 92.

- ^ Arnd Krüger : A Horse Breeder's Perspective. Scientific Racism in Germany. 1870-1933. In: Norbert Finzsch , Dietmar Schirmer (Ed.): Identity and Intolerance. Nationalism, Racism, and Xenophobia in Germany and the United States. University Press Cambridge, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 0-521-59158-9 , pp. 371-396.

- ↑ WM Dugger: Veblen and Kropotkin on Human Evolution. In: Journal of Economic Issues. (18) 1984, p. 971 ff.

- ↑ On the current relevance cf. G. Ortmann: Organization and opening up the world. 2nd Edition. Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 259 f.

- ↑ L. Margulis: The other evolution . Spectrum, Heidelberg 1999.

- ^ M. Speidel: The Parasitic Host: Symbiosis contra Neo-Darwinism . Pli 9 (2000), pp. 119 ff., 120. ( Memento of the original dated December 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 260 kB)

- ↑ P. Winkler: Between culture and genes? Xenophobia from the perspective of evolutionary biology . Analysis & Criticism 1994, pp. 101 ff., 105. ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 2.0 MB)

- ^ Theodosius Dobzhansky, Gordon Allen: Does Natural Selection Continue to Operate in Modern Mankind? In: American Anthropologist. Volume 58, No. 4 (Aug. 1956), p. 591 f.

- ^ Theodosius Dobzhansky, Gordon Allen: Does Natural Selection Continue to Operate in Modern Mankind? In: American Anthropologist. Volume 58, No. 4 (Aug. 1956), pp. 591, 592.

- ^ Theodosius Dobzhansky, Gordon Allen: Does Natural Selection Continue to Operate in Modern Mankind? In: American Anthropologist. Volume 58, No. 4 (Aug. 1956), pp. 591, 597.

- ^ Thomas C. Leonard: Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era. In: The Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 19, No. 4 (Fall 2005), pp. 207, 210.

- ^ T. Schramme: Naturalness as a value. In: Analysis & Criticism. 24 (2002), pp. 249, 252.

- ↑ Another Tradition of Darwinism, Literary Criticism, February 2007.