Gustav Rasch (writer)

Gustav Heinrich Wilhelm Rasch (born November 17, 1825 in Hanover , † February 14, 1878 in Schöneberg near Berlin ) was a German journalist and travel writer who was known for his often polemical texts, but also for his anti-Prussian sentiments and political agitation was.

life and work

Gustav Rasch was born on November 17, 1825 in Hanover as the son of Oberleggemeister Rasch and his wife, b. Koch, born. His father lived in Osnabrück between 1828 and 1839 , where his widow lived in 1848 after his death. It is therefore likely that Gustav grew up in Osnabrück.

According to his own account, he studied law at the University of Göttingen for several years , although it is unknown when he received his doctorate. In any case, he appears in his first book publication The New Bankruptcy Order (1855) as a “Doctor of Both Rights”, which means that he had studied and completed both civil and canon law. In later years he attached great importance to the mention of his doctorate, which was ridiculed by some contemporaries.

As a trainee court trainee, Rasch took part in the revolution in Berlin in 1848 and in particular in the assault on the Berlin armory ; in the latter case he is said to have been "armed with an enormous dragged saber". The action failed on the night of June 14th to 15th due to resistance from the military and vigilante groups, which is why Rasch then had to flee, first to Switzerland and then to Strasbourg and Paris; in the French capital he was to meet Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. After his return in 1849 he was sentenced to imprisonment in Magdeburg.

Early years as a writer

In the first half of the 1850s, Rasch was a legal writer and published several legal handbooks. It can be assumed that due to his political past and criminal record, he had no prospect of government employment, and so he tried to write legal advice that sold well. Be it because he did not have the desired success with it, or be it because his personal inclinations led him in a different direction, he reoriented himself around the mid-1850s and began a career as a travel writer. His horizons expanded from Rügen and the Thuringian Forest to Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland and Northern Italy. His first travel book - Ein Ausflug nach Rügen (1856) - was one of his best-selling books and was advertised and reissued in German magazines for many years. Probably for reasons of sales strategy, however, he designed his following travel books less as travelogues and more as tourist guides with lots of practical information (including hotel reviews and tips for travelers).

His first tourist trips to Austria and Switzerland (1858) marked the beginning of an unsteady life as a traveling journalist, which he led until shortly before his death. In 1875 he was presented in a newspaper as "the nomadic writer". Rasch's travels took him to Italy (1859–1860), London (1865, 1875), France (1863, from 1870), Algeria (1865, then French), Hungary (1866), Romania / Wallachia (1866, 1871), Sweden (1868), Spain (1869), the Netherlands (1869), Greece (1871), Alsace-Lorraine (1873), Tyrol (1874), Transylvania (1877), as well as today's Bulgaria (1871, then "European Turkey") and to Constantinople (1871) and to Serbia (1866, 1871–72) and Montenegro (1871–1872, 1874).

Italy (1859–1861)

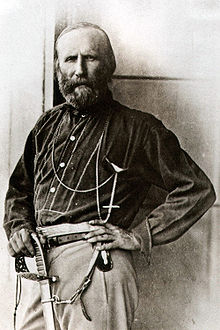

The political events in Italy, with which he undoubtedly came into contact on his first trip to Upper Italy (1858), aroused an enthusiastic nationalism in him, especially when the Italian struggle for independence against Austrian and Bourbon rule entered its hot phase in the spring of 1859 entered. Rasch's whole sympathy and enthusiasm went to the aspirations of the Italian nationalists and in particular to their most important freedom hero and leader, Giuseppe Garibaldi . Rasch himself traveled through Italy from 1859 to 1860, and as a result of his adventures numerous articles appeared as well as his three-volume story of the passion of the Italian people (1860-1862) and an enthusiastic biography of Garibaldi (1863) with the sensational title The Sword of Italy . He dedicated the latter work to the German-English writer Marie Espérance von Schwartz (1818–1899, also known as Elpis Melena), who Rasch had met himself and who played a major role in Garibaldi's life from 1857 and in 1861 published Garibaldi's memoirs in German.

Rasch's strongly anti-Austrian portrayal of the events was received very positively in Italy, especially since he had even sent his books to Garibaldi himself. Marie E. von Schwartz reported the following on this:

"Among several German letters that I had to read to General [= Garibaldi] in order to find out from him how he wanted me to answer them, there was one from Dr. Gustav Rasch from Berlin. This highly praised writer, who is tirelessly trying to promote the cause of freedom in Germany, had accompanied his letter with the third volume of his last book 'Frei bis zur Adria'. - 'Bel titolo, bel titolo, è una bravissima persona quel signor Gustav Rasch' ['A beautiful title, a beautiful title, this Mr. Gustav Rasch is a very great person'] repeated Garibaldi when he picked up the book and the saw the 'mourning queen of the Adriatic' depicted on the title page. "

Outside Italy, sympathy for the Italian nationalists was subdued, at least in semi-official opinion, and Rasch's writings were received with reserve in the German press. A reviewer in the weekly magazine Über Land und Meer wrote that Rasch had “put recent Italian history under the magnifying glass of his party position and told us a story of suffering in these states, which is written in blood instead of ink. We don't count ourselves among the nationality enthusiasts and therefore couldn't find any taste in this book either ”. The Illustrirte Zeitung from Leipzig admitted that Rasch's Garibaldi biography had received “much applause”, although it was written by an “unconditional partisan of the Italian patriot” and gave the overall impression of a “hot-blooded radicalism”.

As expected, the official reaction, especially in Austria, was much harsher. Immediately after publication, in February 1860, the first volume of Rasch's account of recent Italian history was banned "by ministerial order" throughout Austria. A little later the distribution of the work was also prohibited in Prussia and Russia; Rasch and his publisher tried to have the confiscated copies published in Berlin because it was feared that they would be crushed immediately - as happened in Austria. On August 5, 1862, the third volume from Rasch's Frei to the Adriatic Sea was banned “for the entire extent of the Austrian monarchy” by order of the Imperial and Royal Police Ministry; Reasons for the ban included a. "Crimes of high treason", "lese majesty" and "disturbance of public peace". On June 8, 1863, Rasch's Garibaldi biography The Sword of Italy was banned, also for “disturbing the public tranquility”, and on July 26, 1864, the distribution of Rasch's work The New Italy was banned for the same reason.

Schleswig-Holstein (1862–1864)

After his adventures in Italy, during the years 1862 to 1864, the events surrounding the future of Schleswig and Holstein Rasch's full attention. His anti-Prussian sentiments were clearly visible in his writings on the Schleswig-Holstein question and the subsequent Danish-German War (1864), and he also agitated on the ground against Prussia's intervention. Swiftly supported the so-called Augustenburg movement in Schleswig, which called for Schleswig-Holstein to be independent of Prussia; his particular enemy was Count von Scheel-Plessen , around whom those in Schleswig and Holstein who welcomed an intervention by Prussia gathered.

The second volume of Rasch's work Vom Verrathenen Brothererstamme was “seized by the police” in Prussia in May 1864, after having been expelled from the occupied Duchy of Schleswig three months earlier . The official reason was that Rasch had indicated in his book that the aim of the war was “uncertain” and that he had expressed himself “unfavorably” about the Prussian artillery. According to the Prussian public prosecutor's office, this is suitable for inciting “hatred of the Prussian government”. However, the confiscation of Rasch's book could “only be carried out with two copies”, since all the rest were already in private hands.

Jens Owe Petersen rightly judged that Rasch, "although a Prussian citizen himself, embodied in a certain way a kind of fundamental opposition to the government of his home country". Nonetheless, Rasch represented German national interests in a very resolute manner and had also appeared as an anti-Danish agitator since 1862. As early as 1862 there was a controversy about Rasch's contributions in the gazebo (under the title From the Lands of the Abandoned Brother Tribe ) and about his book From the Abandoned Brother Tribe (1862), because in them he spoke of Danish politics in Schleswig in sharp terms had condemned. In February 1863 it was even reported that the Danish government had instructed all police departments to “contact the writer Dr. Gustav Rasch, where he is concerned in the Danish states, to be arrested and taken to Copenhagen under safe cover ”. In addition, the importation of all Rasch's writings into Denmark was prohibited.

Rasch's involvement in the Schleswig crisis had progressed so far in January 1864 that he was generally perceived as an anti-Danish and anti-Prussian agitator at the same time and was presented in German-language newspapers as “the well-known revolutionary”. The following appeal, drafted by Rasch on January 15 in Kiel, was distributed in newspapers and weekly papers, especially in papers from Holstein:

"Call on the German people, describe in your call the need and the danger of the country, demand in this call the immediate convocation of large mass assemblies, as you yourself have just done in Holstein, and be certain: The German people will stand out Raise the Belt to the Adriatic Sea with the battle cry against Denmark: "Forward to Königsau!" At the same time, arm the country. 40,000 rifles can be obtained quickly and easily. Only then will the liberation of the "abandoned fraternal tribe" in Schleswig face all diplomatic intrigues and intrigues as a perfect and compelling fact. "

The reaction to Rasch's appeal was generally frosty, and even supporters of the German-minded Augustenburg movement resisted him. Duke Friedrich VIII of Schleswig-Holstein did not allow Rasch to come to him “as a foreign agitator” and forbade any further interference: “The appeal that this man, who is quite unknown here, addressed to the population (about arming a land army) has passed without a trace , and it has been made sufficiently clear to himself that he should leave as soon as possible. The aforementioned man of letters was well known in individual circles for his acquaintance with Garibaldi ”.

On February 12, 1864, Rasch was arrested by a Prussian officer in Flensburg and taken to the Flensburg city prison because he had allegedly been denounced for "some thoughtless remarks". After 48 hours in detention, however, he was released on the condition "that he had to leave the Duchy of Schleswig by tomorrow at the latest under the prohibition of return", to which Rasch undertook "on his honor". However, he wrote a declaration on February 18 in Kiel, according to which he was merely giving way to “the current violence”, but denying the Prussian government the right to decide whether to enter and leave the Duchy of Schleswig. At the end of February, Rasch went back to Berlin, complained in writing to Bismarck about his deportation and asked for satisfaction. The Prussian civil commissioner for Schleswig, von Zedlitz , immediately refused, with reference to Rasch's proven activity in agitation. This was followed in May by the confiscation of the just published second volume of Rasch's Vom Verrathenen Bruderstamme (see above), but a hearing before the Berlin City Court for Press Offenses ended in September with Rasch's acquittal.

Rasch's partisanship for German national interests in Schleswig-Holstein and his simultaneous rejection of Prussian intervention were closely related to his fundamental, always enthusiastic approval of all national projects in Europe that changed the continent from 1860, beginning with the founding of the Kingdom of Italy and later extended to the national independence movements in Spain and the Balkans (Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria). The major supranational hegemonic powers, primarily the Austrian monarchy and the Ottoman Empire , were the main bogeymen in Rasch's sometimes very polemical writings on the subject.

The traveling journalist (1865–1870)

After the failed attempt to make a name for himself during the Schleswig-Holstein crisis, Rasch stayed away from direct political interference in the years that followed and turned back to writing travel and milieu reports. The beginning of this was his “dark series” (1861 to 1865), a series of articles and books in which he reported from his own perspective about social outsiders and social problems in European metropolises (Berlin, London, Paris). A contemporary reviewer found that Rasch delved into “contemplating the dark side of human life” in these writings “with lust”, which is absolutely true. The boundaries between social criticism, description of the milieu and sensational reports are blurred in Rasch's texts.

A period of intense and restless travel began in Rasch's life in 1865. In February we can still find him in London, where he was a representative of the “democratic party” among the German emigrants there. In the illustrious society of Karl Blind , Ludwig Feuerbach and Ferdinand Freiligrath , it was decided at this meeting in London to publish a separate monthly, which was to appear under the title Der deutsche Eidgenosse and, within a short time, actually - with contributions from Rasch about the executed revolutionary Max Dortu and the revolutionary Gustav Schlöffel who was killed in a battle - appeared.

One month later, in March, Rasch was already in Algeria, then France , and in April traveled to the south of the country (into the Sahara ) via Biskra . A few months after his return from North Africa, from mid-September 1865, a four-week round trip through Schleswig-Holstein followed, about which he wrote a long, much-cited newspaper report. The subsequent book The Prussian Regiment in Schleswig-Holstein , which he published in the spring of 1866, was "confiscated" by the Prussian police shortly after it was published. In this polemical work he supported - as in his earlier writings on the Schleswig question - the anti-Prussian currents in the duchies and also “did not stop at personally discrediting his political opponents in an agitational manner. The sad climax in this sense is a kind of “black list” at the end of his work, in which the name, occupation and place of residence of the “Prussians in Schleswig-Holstein” are recorded “.

In 1866 a trip to Hungary and Wallachia followed. In 1868 he traveled to Sweden before he went to Spain in early 1869 as a “special correspondent” for the Wiener Neue Freie Presse and the Frankfurter Zeitung . There he followed the events of the reorganization of the Spanish state, which after the overthrow of Queen Isabella II led to the constitution of 1869 and a temporary vacancy to the throne. Rasch sympathized with the republican forces.

In January 1870, Rasch moved from Berlin to Paris. In the second half of the 1860s he worked for various German and Austrian newspapers, starting (from 1865) with the Viennese newspaper Die Presse and later with the German-language newspaper Politik in Prague . His almost serial production of books and magazine articles, in which Rasch processed his diverse travel experiences and brought them to the readers, reached a high point in the years 1868–1869. He also tried several times in vain to be elected as a member of parliament (including in Schleswig).

Several lawsuits were brought against Rasch during the 1860s because he was repeatedly charged with insults or defamation, both by private individuals and by the state. In at least one trial, he was sentenced to pay a fine.

Southeast Europe and Alsace (1871–1874)

In 1871 Rasch traveled to Romania , European Turkey (in what is now Bulgaria ), Constantinople and Greece (Athens in particular). In the winter of 1871–1872 he went to Montenegro - often called "The Black Mountain" by him - and then to Serbia (in early summer). At the beginning of July 1872 he was back in Vienna.

In 1871 - after Italy, Schleswig-Holstein and Spain - Rasch discovered the national movements in the Balkans against the rule of the Ottomans as new political and columnist objects of interest. He saw himself (as his friend Friedrich Hackländer attested) as an "eloquent advocate for the peoples between Austria and Turkey". In a letter from Bucharest , dated May 26, 1871, Rasch announced that he had “arrived there on his way to the Orient” and that he “intended to stay in the Orient for a longer period in order to understand the cultural conditions there to study in all parts ”.

Rasch's travel experience in the Balkans served as the occasion for numerous articles and two books, among which the two-volume The Turks in Europe stands out (especially negative; see below). There is no doubt that he was particularly fond of Montenegro, and he dedicated his book The Turks in Europe to Prince Nikola I of Montenegro , with the following lines that are pathetic from today's perspective:

His Highness

the Prince of Montenegro and Brda

Nicola I. Petrović Něgoš

the first knight of the Black Mountain

the illuminator of his tribe

the representative of a five hundred year old, always victorious struggle

against the Asian barbarians in Europe

Nikola I returned the favor in April 1874 by awarding Rasch the Montenegrin Order of Danilo . In October – November 1874, Rasch returned to Montenegro, at which point he had already gained the reputation of a “Montenegrin court journalist” in the Austrian press. A note, which Rasch had undoubtedly launched himself, reports in the magazine Über Land und Meer that Rasch is staying “as a guest of the Prince of Montenegro” in Cetinje : “He lives there in the old palace and has daily dealings with the princes and the Senators ”.

Rasch's main work, which arose from his travels in Southeast Europe, are the two volumes, The Turks in Europe . The first volume covers a. a. his experiences in Belgrade, Romania, Bulgaria and Constantinople, the second his stays in Athens and Montenegro. There are also long digressions on history, culture and political issues. The text is consistently marked by strong hatred of the Turks, especially since Rasch was able to use a much sharper tone towards the Ottoman Empire than in his works, which touched Prussian or Austrian interests. The preface in the first volume of The Turks in Europe begins as follows and leaves no doubt about the author's attitude:

“The Turks have lived on the Balkan Peninsula for almost five centuries, while since their appearance in and against Europe they have fought over a hundred wars, in which the Christians who fell on the battlefield or who fell into Turkish slavery can only be counted by the millions. A nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from Asia (...) has been setting foot on the heads of fifteen million Greek and Slavic Christians (...) for almost five centuries. Nothing is more significant; Nothing characterizes this nearly half-millennium Turkish rule in Europe better and more comprehensively than the well-known saying of a Turkish dervish: 'Where the Turk sets his foot, even the grass withers.' "

These lines set the tone for Rasch's book, and this tenor continues throughout the work. The well-known orientalist Ignaz Goldziher therefore called Rasch's book “hateful” and the author a “fanatical hater of Turks”. A typical feature of vulgar orientalism of the second half of the 19th century can also be made clear in the above quote: Authors and especially journalists who were themselves distant from Christianity or - like Rasch - were strongly anti-clerical, took a verbose approach to Christians Ottoman rule if it served their anti-Turkish rhetoric.

He quickly hoped for a lot from his work The Turks in Europe , but the book turned out to be a boomerang that almost destroyed Rasch's literary career and reputation. It was soon noticed - which, by the way, corresponds to the facts - that Rasch unrestrainedly "written out" older works on the Balkans for many pages without any indication of the source. H. had plagiarized. Two of these older works were The Slavs of Turkey, published as early as 1844 , or the Montenegrins, Serbians, Bosniaks, Albanians and Bulgarians, their forces and means, their striving and their political progress by the French Slavist Cyprien Robert (1807 - approx. 1865) and the book From Orsová to Kiutahia (1851) by Joseph Hutter, where Hutter himself had already made extensive use of Robert. Rasch's plagiarism hit the publisher Jan Stanislav Skrejšovský (1831–1883) particularly hard, whose publishing house not only published Rasch's book but also the newspaper Politik , for which Rasch had regularly written. Skrejšovský had been in custody since August 1872 and was sentenced to one year in prison in May 1873 for evading advertising tax. During his pre-trial detention, Skrejšovskýs Verlag suffered such severe losses that he felt compelled to sell it together with his printing company. Rasch's plagiarism script played a major role, as reported in the Wiener Zeitung Die Presse :

“[At the same time] Gustav Rasch, the longtime loyal employee of 'Politics', gets off very badly. Politics brought a long series of feature articles from the Orient by him, and later had them printed as a separate edition at great expense. When the bulky book was finished, advertisements published its appearance and Serbia, the Moldau and the Black Mountains [Montenegro], even the Bocchese were already made receptive to the reception of the epoch-making national work, the discovery was made that it was nothing more as a copy of the older writings of well-known travelers to the Orient and the maculature is now piled up to the ceiling in the paper magazines of 'Politics' and the damage runs into the thousands. "

The same was true not only for Rasch's The Turks in Europe , but also for his work The Lighthouse of the East: Serbia and the Serbs, also published by Skrejšovskýs in 1873 . In this book Rasch used Serbia unscrupulously and over many pages in the work published in 1868 . Historical-ethnographic travel studies from the years 1859–1868 by the Austro-Hungarian researcher Felix Kanitz (1829–1904). Kanitz - who reacted extremely sensitively to plagiarism, although he sometimes withheld sources himself - complained clearly in a later edition of his work and spoke of Gustav Rasch as the "famous prolific writer (...) who came from my" Serbia "published in 1868 "Lighthouse of the East" made ".

How damaged Rasch's reputation was after these very justified allegations of plagiarism is difficult to say, especially since not everyone who later quoted from Rasch's books was aware of the allegations of plagiarism. But it is significant that after 1873 Rasch did not publish anything related to Southeast Europe. Only his reports from Montenegro still appeared in some magazines and in book form in the spring of 1875 under the title Vom Schwarzen Berge. Montenegrin sketches, pictures and stories . But even when the events in the Balkans in 1876 (uprisings in Serbia and Bulgaria ) and 1877 ( Russian-Ottoman War ) met with great interest from the German-speaking public and all sympathizers of national movements rushed to this issue, Rasch no longer spoke publicly. However, he had already found a new field of activity in the summer of 1873, which also brought him back to his political origins and his old aversion to everything Prussian.

In July 1873 - a few days after the official proclamation of the incorporation of Alsace-Lorraine into the German Empire - Rasch traveled to Alsace-Lorraine, which after the victorious Franco-Prussian War was annexed by the German Empire as an empire and was administered by Prussia. As usual with him, this trip resulted in a book, namely the indictment The Prussians in Alsace and Lorraine , published early next year . In it he castigated the Prussian policy in the newly acquired Reichsland, which in his opinion was nothing but a "bondage of the spirits"; He also spoke of a "Prussian war of annihilation against the French language and education" in Alsace-Lorraine. As expected, the book was confiscated at the beginning of March 1874, shortly after its publication, by order of the police headquarters in Berlin. A later part of the book about Alsace was a trial for lese majesty and other offenses brought against Rasch in Braunschweig in February 1876; Schnell himself did not appear. The Braunschweig district court then did not recognize insult to majesty, but sentenced Rasch - in absentia - to ten months' imprisonment "for mutual irritation of the population classes and dissemination of fabricated and deformed facts". In May the higher court in Wolfenbüttel revised the sentence and now ruled for four months.

The last years (1874–1878)

In the spring of 1874, Rasch published the last of his many tourist guides under the provocative title Tourist Pleasure and Sorrow in Tyrol . He did not skimp on the most violent criticism of Catholic Christianity and enjoyed polemical remarks of all stripes, so that the book soon became the talk of the town in the region concerned and in all of Austria. Rasch's book “really does no less great things in abuse of the strong faithful Tyrolean people and their customs, as in ignorance, distortions and historical lies. Pusterthal and Meran get off particularly badly, of course because Rasch doesn't seem to have been anywhere else, ”said the Salzburg Chronicle. People were particularly appalled in the Pustertal , where the Pusterthaler Bote published in Bruneck printed an angry replica of Gustav Rasch's Tyrol book. The reviewer wrote that even while reading “Rasch's Schmiere” he only felt “disgust and severe nausea”. “So much dirt, so much self-arrogance, so much cheeky lies and deliberate distortion can only be achieved by an individual like Gustav Rasch; but that a decent printing company can publish such a literary manure pile is incomprehensible to me ”. Other Austrian newspapers and journals produced similar replicas, and Rasch had become a persona non grata in Tyrol for the time being.

A visit to England in 1875 brought Rasch back into personal contact with old acquaintances from the revolutionary era, although they were by no means all good on Rasch because they accused him of ignorance of the conditions in England. Rasch began to think back to the revolutionary time as early as 1867, when he and Gustav Struve wrote the work Twelve Warriors of the Revolution , which included the life pictures of foreign (including Camillo Cavour and Michail Bakunin ) and German revolutionaries. This was followed a year later by the autobiographical book From my fortress time , the title page of which shows a portrait of Rasch behind a lattice window; the book had to be published by a Viennese publisher because no German publisher could be found. Both writings, especially the Twelve Streiter , had quickly made a name again among the German emigrants in London; Even Karl Marx was very familiar with this book shortly after it was published, although he wrote in a letter to Ferdinand Freiligrath that he did not read “German junk fiction”. At an unknown point in time in 1872, Rasch also joined the SDAP , which had been founded three years earlier. During his stays in Vienna he corresponded with Friedrich Engels in 1875 and 1876 .

Rasch lived in Paris during 1876. In this way, he also evaded the prison sentence imposed in February / May, which is why the public prosecutor in Braunschweig issued a profile for Rasch in June, which, however, could not be executed either.

In the spring of 1877 he moved to Vienna and made a short trip to Transylvania . Rasch's interest in these years had turned back to the darker sides of modern society, which he had already covered in the books of his “dark series” during the 1860s: prisons, insane asylums, women's shelters and other symptomatic institutions of industrial societies of the 19th century.

In mid-November 1877, Rasch suffered a severe stroke in his home town of Mödling near Vienna, which resulted in partial paralysis. Despite the resulting bedriddenness, he had Mödling bring him to a mental institution in Berlin-Schöneberg in December, which was made possible by a special train that Baron Rothschild had made available to him in Vienna. In Berlin, Rasch died a few weeks later, on February 14, 1878, as a result of the stroke.

Even in the days after his death, Rasch caught up with his political past. Newspapers reported that he would be remembered by Berliners as a “tax refuser” because he “owned assets but refused to pay taxes for political reasons”.

Contemporary reception

In view of the political activities, but also in view of the content and style of his writings, it is hardly surprising that opinions differed on Gustav Rasch.

On the part of political comrades-in-arms who shared his democratic convictions and his commitment to national movements, he earned great approval, and sometimes even admiration. His activities during the Holstein crisis were particularly influential in his later reputation, and as early as 1862 Heinrich Mahler (1839–1874) dedicated his twelve sonnets for the "abandoned brother tribe" (Berlin: A. Vogel) to his "friends and spiritual ones Comrade in arms, Mr. Gustav Rasch ”. As “the well-known, witty and tireless traveler” and “the persistent champion for the rights of the Schleswig-Holsteiners when they were still sighing under Danish rule,” Gustav Rasch appears in the thirteenth chapter of the “contemporary novel” Two Imperial Crowns by Oskar Meding in the magazine Über Land und Meer and was published as a book in Stuttgart in 1875.

Other positive voices saw less of his political stance than of his work as a writer, for example in the judgment of a reviewer from 1870: “ Michael Klapp , Hans Wachenhusen and Gustav Rasch, this is a tourist trifolium, which the reader is on every step and step, and very happy to meet. In the Sahara and on the coasts of Norway, in Spain and in Egypt, in Paris and Rome, these people are at home and delight us with cheerful and lifelike images of life from all areas ”. After his flood of publications in the years 1868–1869, Rasch - "the well-known Weltschmerz traveler" - became a much-cited author in the following years, albeit mainly because of the incessant succession of texts that flowed from his pen. His reports from Southeastern Europe ennobled him for a short time as a “well-known traveler to the Orient”, until the failure of his book The Turks in Europe put an end to it.

The criticism of Rasch's work, however, prevailed. This criticism was ignited both by his journalistic, flippant style, but also by the many inaccuracies and errors that his writings contain. His style was considered by many to be poor in expression and as the result of an author who hastily wrote his texts down with little care or - as one would say today - "slouched". As far as the content of his works was concerned, it even happened that Rasch's embarrassing errors were presented publicly and with great gusto in newspaper articles, for example when he described Emperor Sigismund as "known to be a Jesuit student" in an article , which of course was a stupid mistake. because the founder of the Jesuit order was only born 54 years after Sigismund's death! His writings on Montenegro were also criticized: “Gustav Rasch did not give us a true picture of Montenegro; he probably did not idealize the country, but he Europeanized it in his writings and has thereby here and there not corresponded to the truth ”.

Others took offense at the fact that Rasch presumed to be able to report comprehensively and competently on a place after a stay of a few days. This criticism was entirely justified. For example, one reviewer wrote of Rasch's book The Lighthouse of the East: Serbia and the Serbs (1873):

“But whoever wants to dig up these treasures must know the vernacular, he must be a good observer and psychologist. Gustav Rasch has been there for a long time and has finally published a long book about Serbia. I can assure you that he never spoke a single word to a man from the people because he did not understand a word of Serbian. As a lawyer, he could have had a rich harvest here quickly, but because of ignorance of the vernacular he had to grope around like a blind man and be content with what good-natured people dictated to him in his notebook. "

Such criticism is often formulated in passing, for example in the review of the book Venetian Life (1866) by William Dean Howells , where Gustav Rasch's writings serve as a negative example for the reviewer: “The presentation is all the more unselfconscious as it is penned the North American consul Howells, who has lived in Venice for three years and, thanks to multiple family connections, is probably better able to describe the inner life of the city than those tourists who spend a short time in the inn and then their fancy pen sketches à la Bring Gustav Rasch to the bookselling market. "

Finally, Rasch, who admittedly liked to hand out himself, had to put up with biting ridicule. This was primarily aimed at his political ambitions and his tendency to interfere as a journalist in relatively far-reaching processes, as was the case in Schleswig-Holstein or in some cases in Spain. Paul Lindau made fun of Gustav Rasch's trip to Spain in 1869. He calls Rasch the "columnist liberator of the people" and mockingly throws into the room that Rasch did not actually go to Spain to report from there, but to apply for the Spanish throne himself. Lindau's ridicule then leads to a fictional speech from the throne, as it could have made Rasch in front of the Spaniards:

“Hidalgos (...), you have chosen me to be your ruler. I thank you. I know you. I read Garrido's history of modern Spain and faithfully carried it with me in my suitcase. You know me Because everyone knows me. I'm a doctor of both rights, a friend of Garibaldi’s , Victor Hugo’s , Karl Blind’s and many other important personalities. I suffered for freedom. I had to go for a walk in Magdeburg for a long time. I was in the dungeon. I've said that many times before, but you can never say something like that often enough. I smashed Scheel-Plessen and invented the 'Prussian plague'. I liberated the abandoned brother tribe and Italy as far as the Adriatic. I wandered all over Europe and made most of the German newspapers unsafe with my descriptions from all over the world. I am a cosmopolitan by inclination and profession. Take no offense at my foreignness! Just ask the Germans if my style doesn't seem completely Spanish to them. "

A few years later the Berlin satirical magazine Kladderadatsch began to make fun of Rasch's political ambitions and self-importance in the national affairs of other nations, in regular succession. Between February 1874 and July 1876 a total of five humorous short articles were published that revolved around this topic; they targeted Rasch's previous activities and journalistic forays: Italy, Schleswig (“the abandoned tribal brothers”!), Montenegro and even his trip to the Sahara:

"[1] A storm is gathering in the distance over the head of the Chancellor. The Tunis newspapers, run from the Prussian Reptile Fund, had long been working towards a palace revolution. The plan was to raise the well-known travel agent of the Prussian government, Gustav Rasch, to bey of Tunis (which is known to be the key to the Sahara). This fine plan fails, however, because the population of Tunis is quite satisfied with the current Bey, who only beheads twice a week, and does not want any change. So another hit in the water!

[2] On the other hand, Gustav Rasch slept quietly in a snow-covered alpine hut on the Black Mountains. He dreamed that, following a letter of recommendation from Garibaldi, he had been chosen to be the sultan of the abandoned tribe brothers in Sumatra. When he woke up, he was shuddered to learn that the princess "Stibitzka with the raven hands", who had spent the night at the same alpine hut, had secretly made off with his, Gustav's, white cylinder into the mountains, where freedom lives.

[3] As far as we know, Gustav Rasch is determined not to accept the defunct throne of China.

[4] A prince is being sought for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Where is Gustav Rasch? And would he, out of gratitude for the prince's hat, also take over the task of putting Turkey's finances in order?

[5] Prince Nikita of Montenegro has been appointed Prince of Herzegovina by the insurgents. Mr. Gustav Rasch should already be with him, in the expectation that he too will now either be proclaimed field marshal, finance or culture minister of the abandoned brother tribe. "

Quotes from contemporaries

“In the forefront of these new sensational publicists is the well-known Dr. Gustav Rasch. Everywhere where the events of the present can be used in this sense, where a sudden "catastrophe", a government overthrow, dethronement or the like surprises the world, where accidental or forced revelations promise a rich gain in sensation and scandal, see everywhere we have the mobile Gustav Rasch, who is constantly on the qui-vivo, who is traveling forever, at hand to serve the audience the spicy fruits of his perceptions, impressions and encounters. "

"Gustav Rasch, who writes a lot, is known as a writer who is not concerned with the careful formal implementation of a subject, but only with arousing an objective interest in an outwardly extremely casual [ǃ] form"

“That was the well-known, grim republican, author of 'Schleswig-Holstein, meerumschlungen', the inventor of the 'Prussian plague', who on paper dealt with the most devastating tirades and most radical things, and was as soft as a cow in life . "

Critical appraisal

The writer Rasch and his work were more or less forgotten soon after his death. This applies both to his political writings (which had long since lost their daily relevance) and to his travel reports and travel guides. Unlike many of his contemporaries and colleagues in the German feuilleton, he did not make an entry in Franz Brümmer's influential lexicon of German poets and prose writers from the beginning of the 19th century to the present (1913). In 1917, an author remembered Rasch and introduced him to his readers as “a German travel writer who is not widely read”.

Nevertheless, Rasch was a very typical phenomenon in the German-speaking media landscape and journalism after the middle of the 19th century and must be placed in line with Friedrich Hackländer , Hans Wachenhusen , Julius von Wickede , Moritz Hartmann and many others. As professional journalists, they all lived off their texts and therefore always had to keep an eye on what could be best sold and produced the fastest, and what impressed the public most on their names. For this purpose, it made sense to write travel reports, which experience has shown to sell well in this mobile age in which modern tourism was invented. It was just as obvious to provide coverage of political crises and wars or sensational reports, the content of which could be sure to attract the readers' attention. A flippant and disrespectful style also promoted sales, which worked all the better when peppered with sarcasm and malicious polemics. Schnell pursued all of these strategies in exemplary form, and his “dark series” justifies seeing him as a “sensational writer”. The fact that Rasch is still not considered a German Mark Twain today, but has essentially fallen into oblivion, has to do with the fact that his often malicious talkativeness is not remotely reminiscent of the witty (albeit equally malicious) texts of the US journalist reaches.

What set Rasch apart from many of his fellow columnists was his active participation in the revolution of 1848 and his urge to deliberately provoke state power in Prussia and Austria, which continued to break out in later years. It is not clear whether it was always about defending liberal or democratic ideals, as he pretended. It seems to have been a question of character for him, because actually almost all of his writings are brushed on provocation, in the case of Swiss inns or Tyrolean Catholicism as well as in the case of his disdain for Turkish culture or when he faces the intrigue of a Berlin theater director assumed. In addition, the rapid development of the press after 1850 and the multiplication of print media gave Rasch and his colleagues the feeling of omnipotence that their literary series production was the tip of the balance in a modern society, and that their own activities were therefore of the greatest relevance in all questions that are currently were on the agenda. Rasch himself said: In response to the reproach of the Prussian civil commissioner (who in March 1864 had declared Rasch's expulsion from Schleswig to be legal) that Rasch behaved as if he were “the representative of a great power”, he replied: “Of course I am Representatives of a great power, namely the most powerful and influential, namely the press ”.

The part of Rasch's work that is perhaps most likely to win a today's reader in for him are his numerous reports about the socially excluded and disadvantaged, which he traced in Paris, Berlin, London and Vienna. It is also no coincidence that these are the only texts by Rasch that were "rediscovered" and reissued in the 20th century. His striking fascination with prisons and madhouses may stem from - as a contemporary noted - that he himself was "imprisoned as a political criminal, so he deals a lot with those who have to atone for the loss of freedom".

After all, it was thanks to Rasch that he brought three winged expressions into circulation which, even after his death, were remembered longer than his countless writings:

- Free to the Adriatic . Quickly popularized this slogan, which soon became generally related to the Italian national movement. He originally came from Napoleon III . War manifesto of May 3, 1859, but it was not until Gustav Rasch's book of the same title that it became a household word in German-speaking countries.

- The abandoned brother tribe . Rasch invented - in connection with the Schleswig-Holstein crisis - the image of the "abandoned brother tribe". However, Rasch was to follow this image in the German press while he was still alive, because it was mainly used against him by those who ridiculed his political stance and enthusiastic nationalism.

- The Prussian plague . Rasch is considered to be the originator of the term “Prussian disease”. He said of himself that he was "the discoverer of this new peoples epidemic", and what he meant by that emerges from a section that hededicated to the German emigrants in Barcelonain his book Vom Spanisch Revolutionsschauplatze (1869):

“All the more disgusting (…) was the impression my Prussian compatriots made on me in Barcellona. I have not been able to discover a single one of them who was not afflicted by the Prussian epidemic. Well puffed up by the glory of the battles fought in Bohemia and the victories they had won, they strutted about Barcellona, imagining that they had become something among the peoples of Europe through the deaths of hundreds of thousands, the bullets and the diseases of people who had been slain. In their opinion, the unity of the German nation could only emerge from the continuation of such a bloody policy of conquest, which would have to spread over all of Germany. "

In fact, the term “Prussian epidemic” soon became an integral part of the political vocabulary of the German feature pages and is in frequent use. Especially after 1870 it was often used in the Rasch sense, namely to designate a “megalomania that swarmed in Bismark”.

Private life

Gustav Rasch was married to the Hungarian opera singer and soprano Rosa de Ruda (own Róza Bogya de Ruda, 1835-1919). She made her debut at the Budapest Opera in March 1854 and then worked as a celebrated opera singer for over two decades. She outlived her husband by more than four decades and died in Berlin. She gave singing lessons in Berlin for over three decades, and well-known opera singers received their training from her.

It is possible that she met Rasch when she performed with the opera company of the Italian impresario Achille Lorini at the Victoria Theater in Berlin, which opened in 1859, between January 1860 and the end of March 1861 . During the first half of the 1860s she was engaged mainly in Italy, Romania and England (spring 1863), in later years mainly in Germany, namely at the Berlin Court Opera .

There is no information about the exact time of their marriage. In June 1862 it was announced that “the popular singer Fr. Rosa de Ruda” was visiting her family in Baden near Vienna. In newspaper reports from 1862 onwards, she was generally no longer presented as a "Miss", but as a "Frau" or "Signora", which could indicate that she was married. This is contradicted by the fact that “Signora” may only have been part of her artist name (“Signora de Ruda”), which she had been using since 1857 and under which she also appeared in Berlin from 1860–1861. The news over the next few years remained contradictory, and in several newspaper articles from 1863 and 1866 she was again called "Mademoiselle" or "Fräulein". The name of a possible husband is nowhere mentioned.

Honors

- Awarded the Montenegrin Order of Merit Danilos I by Prince Nikola I. Petrović Njegoš (April 1874)

Works

Travel writings

Books

- 1856: A trip to Rügen. Nature, people and history of the island . Leipzig: JJ Weber. Second edition udT A trip to Rügen. Illustrated travel guide (1860)

- 1858: The Thuringian Country and the Thuringian Forest. A travel book through Thuringia in sketches and pictures . Leipzig: CA Haendel

- 1858: no money, no Swiss! Travel calendar for Switzerland to the year 1858. For protection for German travelers . Berlin: Otto Janke

- 1858: Southern Bavaria, Salzburg, Salzkammergut, Tyrol, Upper Italy. New guide for travelers . Berlin: Otto Janke

- 1861: Highland trips . Berlin: Otto Janke

- 1861: Italian hiking book: The Alpine Roads - The Lakes - The Venetian and Lombard Cities. With an appendix: Red and Black Book of Inns . Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp.

- 1861: To Ischl, Salzburg and Gastein . Berlin: Otto Janke

- 1866: To the oases of Siban in the great Sahara desert. A travel book through Algeria . Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp. Second, revised edition in 2 volumes udT To Algiers and the oases of Siban , Dresden: W. Baensch 1875

- 1867: The peoples of the lower Danube and the oriental question . Breslau: Joh. Urban Kern

- 1868: From the North Sea to the Sahara . Berlin: Berlin: House Friends Expedition

- 1869: From a free country. A travel book through Sweden . Pest - Vienna - Leipzig: A. Hartleben

- 1869: From the Spanish revolution scene . Spanish conditions, characteristics and history . Pest - Vienna - Leipzig: A. Hartleben

- 1873: The lighthouse of the east: Serbia and the Serbs . Prague: JS Skrejšovský

- 1873: The Turks in Europe . 2 volumes. Prague: JS Skrejšovský

- Modern Turkish edition: 19. yüzyıl sonlarında Avrupa'da Türkler . Ub. Hüseyin Salihoğlu. Istanbul: Yeditepe 2004

- 1874: Tourist pleasure and suffering in Tyrol. Tyrolean travel book . Stuttgart: CF Simon

- 1874: From days gone by. Historical pictures and sketches. First row: Dresden's famous houses and palaces . Dresden: GA Kaufmann

- 1875: From the Black Mountains. Montenegrin sketches, pictures and stories . Dresden: Wilhelm Baensch (Collection of German and Foreign Fiction 34)

- Modern Serbo-Croatian edition: Crna Gora u pričama . Ov. Tomislav Bekić . Podgorica: Cid 2001 ISBN 86-495-0202-4

Articles, essays (selection)

- One day in Milan . In: The Gazebo . Volume 5, 1859, pp. 69–72 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Italian sketches. No. 1: Como . In: The Gazebo . Issue 9, 1859, pp. 125–128 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- The penitentiary's house . In: The Gazebo . Volume 6, 1860, pp. 87-90 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- A dentist in Florence . In: The Gazebo . Issue 39, 1860, pp. 624 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1865: An African pleasure garden . In: Die Presse (Vienna), No. 78 (March 19, 1865), p. 2 f. (not paged)

- 1865: The festival of Mahomed’s students . In: Die Presse (Vienna), No. 98 (April 9, 1865), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1865: A walk through Algiers . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 28 (April 1865), pp. 435–438; No. 29, p. 459

- 1865: In the bagno of the galley convicts in Toulon. A travel report . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 34 (May 1865), p. 534 f.

- 1865: From the sea to the desert . In: Die Presse (Vienna), No. 203 (July 25, 1865), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1865: Arab women and girls in Africa . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 46 (August 1865), p. 726 f .; No. 47, p. 747; still reprinted in the supplement of the New Foreign Gazette , No. 217 (December 17, 1865), p. 1 f. (not pag.).

- 1865: A visit to the Sheik of Lischana in the Sahara desert . In: Die Gartenlaube , Heft 20 (1865), pp. 313-315

- 1865: A ride through the Sahara desert . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 50 (September 1865), pp. 787–790

- 1865: A trip to Lauenburg . In: Morgen-Post (Vienna), No. 297 (October 27, 1865), p. 1 f. (not paged). Taken from the Schleswig newspaper .

- 1867: The Place of Festivals in Paris . In: Die Illustrirte Welt (Stuttgart), No. 28 (1867), p. 326 f.

- 1866: One day in Bucharest . In: The Gazebo . Issue 26, 1866, pp. 409-411 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1867: From my time as a refugee. Reminder sheets . In: Die Illustrirte Welt (Stuttgart), No. 29 (1867), p. 342 f .; No. 30, pp. 354-356; No. 37, pp. 436-438; No. 49, pp. 582 f .; No. 51, pp. 603-606; No. 52, p. 618 f. [mainly reports on Rasch's stays in Strasbourg, Paris and London]

- 1867: Wallachian contrasts . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 21 (February 1867), pp. 328–330

- 1867: An island of the floating sea city. Murano and its glass workshops . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 23 (March 1867), pp. 368–370

- 1867: A visit to Hanover . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1077 (August 31, 1867), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1867: Frankfurt walks . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1125 (October 18, 1867), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1868: a madhouse . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1311 (April 24, 1868), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1868: The oldest cemeteries in Europe . In: II. Supplement to the New Foreign Gazette (Vienna), No. 259 (September 20, 1868), p. 1 f. (not paged); Constitutionelle Bozner Zeitung , No. 224 (September 30, 1868), p. 1 f. (not paginated), no. 225 (October 1, 1868), pp. 1–3 (not pag.)

- 1868: A visit to Upsala . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1463 (September 26, 1868), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1868: A visit to the Friedländer House in Prague . In: The Bazaar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung , No. 40 (October 23, 1868), p. 319 f.

- 1869: Bohemian hunger towers . In: Der Hausfreund (ed. H. Wachenhusen ), 12th year (1869), issue 1–4

- 1869: a Spanish adventurer . In: Der Hausfreund (ed. H. Wachenhusen ), 12th year (1869), issue 13-16; Bozner Wochenblatt , No. 164 (July 23, 1869), p. 1 f.

- 1869: European cell prisons . In: Abendblatt der Tagespost (Graz), No. 21 (January 23, 1869), p. 1 f. (not pag.); No. 24, p. 1 f. (not paged)

- 1869: Skjuts trip to Arcadia . In: The Bazaar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung , No. 8 (February 23, 1869), pp. 63 f .; No. 10 (March 8, 1869), p. 79

- 1869: From the Spanish revolution scene . In: New Free Press. Morgenblatt , No. 1633 (March 16, 1869), p. 1 f. (not paged); No. 1648 (April 1, 1869), pp. 1 f. (not pag.)

- 1869: The Berlin Aquarium . In: Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig), No. 1349 (May 8, 1869), p. 351

- 1869: Europe's most famous waterfall . In: New Free Press. Morgenblatt , No. 1712 (June 5, 1869), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1869: Two royal dungeons in Gripsholm Castle . In: The Debate. Morning Edition , No. 164 (June 15, 1869), pp. 1–3 (unpaginated)

- 1869: The Regent of Spain . In: New Free Press. Morgenblatt , No. 1732 (June 25, 1869), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1869: A train journey in Sweden . In: Der Welthandel (Stuttgart), No. 1, Issue 5 (1869), pp. 275–280

- 1869: From the singer of the Frithiofssage . In: The Bazaar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung , No. 32 (23 August 1869), p. 259 f.

- 1869: Holland's most beautiful city . In: Die Illustrirte Welt (Stuttgart), No. 21 (1869), p. 251 f .; No. 22, p. 263 f.

- 1869: Holland's oldest city . In: Die Illustrirte Welt (Stuttgart), No. 25 (1869), pp. 292–295

- 1872: A visit to a Serbian monastery . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 8 (1872), p. 157 f.

- 1872: A Roman imperial palace in Dalmatia . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 12 (1872), p. 226 f.

- 1872: A Turkish fortress in Serbia . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 13 (1872), p. 247; Community newspaper. Independent, political journal (Vienna), No. 68 (March 21, 1873), p. 11; No. 70, p. 17 (supplement); No. 73, p. 11

- 1873: A visit to the Zwornik area . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 19 (1873), p. 373; No. 21, p. 413 f.

- 1873: From Rustschuk to Varna . In: Europe. Chronicle of the Educated World (Leipzig), No. 33 (1873), Col. 1046-1054.

- 1874: The new Russian church in Dresden . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 4 (1874), pp. 71–74

- 1874: The high valley of Lienz . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 11 (1874), p. 215 f.

- 1874: A Berlin madhouse [!] . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 49 (1874), pp. 977 f .; No. 50, pp. 997-999

- 1875: Pictures from Montenegro . In: Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig), No. 1659 (April 17, 1875), pp. 291–293; No. 391-393; No. 1670 (July 3, 1875), p. 9.

- 1875: My second ride up the black mountain . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 22 (1875), p. 437 f .; No. 1664 (May 22, 1875), 26, p. 514 f.

- 1875: An English remand prison . In: Morgen-Post (Vienna), No. 240 (August 30, 1875), pp. 1–3 (not paginated)

- 1875: A madhouse in London . In: Morgen-Post (Vienna), No. 289 (October 18, 1875), p. 5 (not paginated); No. 296 (October 25, 1875), p. 5 (not pag.)

- 1876: Paris misery and crime . In: Omnibus. Illustrirtes Familienblatt (Hamburg), No. 24 (1876), pp. 405–407

- 1876: From a convent of the Sisters of Charity in Paris . In: Supplement to No. 235 of the "Grazer Wochenblatt" of October 13, 1876 , p. 2 (not paginated)

- 1876: A Paris refuge . In: Supplement to No. 241 of the "Grazer Wochenblatt" of October 20, 1876 , p. 1 (not paginated)

- 1877: A trip to Hunyad over the Giant Iron Mountain. A Transylvanian travel sketch . In: The home. Illustrirtes Familienblatt , No. 25 (1877), p. 405 f.

- 1882 ( posthumously ): Pictures from Transylvania . In: The Salon for Literature, Art and Society . Volume 1 (1882), pp. 445-451, pp. 571-579

- 1883 ( posthumously ): A pirate town in Africa . In: Marburger Zeitung , No. 38 (March 30, 1883), p. 2 f .; No. 39 (April 1, 1883), p. 1 f.

Contemporary history and biographical issues

Books

- 1860–1862: Free to the Adriatic Sea: History of suffering of the Italian people under Austrian rule since the Peace of Villafranca . 3 volumes.

- Volume I: Austrian government history in Italy . Berlin: Gustav Bosselmann 1860

- Volume II: History of the suffering of Italy under Austrian, papal and Bourbon rule: Veneto. Modena. Rome. Naples. Sicily. Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp. 1861

- Volume III: The Mourning Queen of the Adriatic . Berlin: Reinhold Schlingmann 1862

- 1862: The new Italy . Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp.

- 1862: From the abandoned brother tribe. The Danish regiment in Schleswig-Holstein . 2 volumes. Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp. A second edition appeared in the same year.

- 1863: The Sword of Italy. Life sketch of General Josef Garibaldi . 2 volumes. Berlin: Nelte, Böltje & Comp.

- Italian (part) edition: Garibaldi e Napoli nel 1860: Note di un viaggiatore prussiano . Ex. Luigi Emery. Bari: Laterza 1938

- 1864: From the betrayed brother tribe. The war in Schleswig-Holstein in 1864 . 2 volumes. Leipzig: Otto Wigand

- Volume I: The Federal Execution in Holstein

- Volume II: The War in Schleswig

- 1866: The Prussian regiment in Schleswig-Holstein . Kiel: Carl Schröder & Comp.

- 1867 (together with Gustav Struve ): Twelve fighters of the revolution . Berlin: R. Wegener

- 1868: Baron Carl Scheel-Plessen. Who he was and who he is? . Hamburg - Berlin

- 1868: From my time as a fortress. A contribution to the history of the Prussian reaction . Pest - Vienna - Leipzig: A. Hartleben

- 1870: Today's Spain . Stuttgart: A. Kröner. Second edition. Stuttgart: JG Kötzle 1871

- 1871: From Louis Bonaparte’s debt register . 3 volumes. Stuttgart: A. Kröner

- 1874: The Prussians in Alsace and Lorraine . Braunschweig: W. Bracke jr. A second edition appeared in the same year.

- French edition: Les Prussiens en Alsace-Lorraine, par un prussien . Ex. Louis Leger. Paris: E. Plon & Cie. 1876

Articles, essays (selection)

- 1861: Garibaldi's soldiers in Genoa . In: The Gazebo . Issue 37, 1860, pp. 590 f . ( Full text [ Wikisource ] - dated Livorno, August 26th).

- 1861: From the Italian theater of war . In: The Gazebo . Issue 46, 1860, pp. 735 f . ( Full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1861: The use of torture in the prisons of Naples and Sicily. No. 1 . In: The Gazebo . Volume 5, 1861, pp. 69–72 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1861: The use of torture in the prisons of Naples and Sicily. No. 2 . In: The Gazebo . Issue 8, 1861, pp. 118–121 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1861: The current situation in Schleswig-Holstein. I. A Danish Sunday in Fishing . In: Deutsches Magazin , Volume I (1861), pp. 294–298

- 1861: The current situation in Schleswig-Holstein. II. A Danish reader for German elementary schools and higher schools in Schleswig . In: Deutsches Magazin , Volume I (1861), pp. 347–352

- 1864: In the dungeon of the hopeless . In: The Gazebo . Issue 1, 1864, pp. 8–10 ( full text [ Wikisource ] - from Paris).

- 1864: From the lands of the abandoned brother tribe. 1. A visit to Rendsburg . In: The Gazebo . Volume 5, 1864, pp. 75–76, 78 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1864: From the lands of the abandoned brother tribe. 2. From Rendsburg to Schleswig . In: The Gazebo . Issue 9, 1864, pp. 142 f . ( Full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1864: From the lands of the abandoned brother tribe. 3. From Schleswig to Rendsburg and my capture by the Prussians . In: The Gazebo . Issue 10, 1864, pp. 157–159 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1864: From the lands of the abandoned brother tribe. 4. From Schleswig to Missunde . In: The Gazebo . Issue 12, 1864, pp. 187–190 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1865: In Monte-Christo's dungeon and the iron mask . In: The Gazebo . Issue 12, 1865, pp. 185–188 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1865: Returned from exile . In: The Gazebo . Issue 29, 1865, pp. 453–455 ( full text [ Wikisource ] - via Gustav Struve ).

- 1865: The "first worker in France" . In: The Gazebo . Issue 37, 1865, pp. 588-590 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1865: A wreath of immortelles on the grave of a martyr (Max Dortu) . In: Der deutsche Eidgenosse (London), 1865, pp. 18–24 (about Maximilian Dortu )

- 1865: a champion of the revolution . In: Der deutsche Eidgenosse (London), 1865, pp. 82–88 (about Gustav Adolph Schlöffel )

- 1865: From the home of the abandoned brother tribe . In: Der deutsche Eidgenosse (London), 1865, pp. 162–166

- 1867: The singer of the Orient and freedom: Ferdinand Freiligrath . In: Die Illustrirte Welt (Stuttgart), No. 38 (1867), p. 450 f.

- 1868: From the death room of an executioner . In: Morgen-Post (Vienna), No. 154 (June 5, 1868), p. 1 (not paginated); Znaimer Wochenblatt , No. 23 (June 7, 1873), p. 247 f.

- 1868: A dispute over a dead man . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1388 (July 12, 1868), pp. 2-4

- 1869: Spanish court stories . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 27 (April 1869), p. 438; No. 28, pp. 460-462; No. 29, p. 468 f.

- 1869: The Prince of Romania . In: Tagespost (Abendblatt) , No. 340 (December 21, 1869), pp. 1–3 (not paginated); No. 341, pp. 1-3 (not pag.); No. 342, p. 1 f.

- 1870: Alexander Hertzen . In: New Free Press. Morgenblatt (Vienna), No. 1944 (January 27, 1870), p. 1 f. (not paged)

- 1870: From Louis Bonaparte's debt book. The devil island . In: Die Gartenlaube , Heft 14 (1870), pp. 218-220

- 1870: A visit to Henri Rochefort . In: The Gazebo . Issue 18, 1870, pp. 280–282 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- 1870: The kidnapping from the Dominican convent . In: Book of the World .

- 1872: Prince and reign of Serbia . In: Über Land und Meer , No. 2 (1872), pp. 23–26

- 1876: A pupil of Cagliostro’s . In: Morgen-Post (Vienna), No. 69 (March 10, 1876), p. 1 f.

- 1876: German refugees in London . In: The People's State of July 30, 1876, p. 1 f.

The "dark series"

- 1861: The dark houses of Berlin . Berlin: A. Vogel & Comp. / 2nd increased and completely revised edition. Wittenberg: R. Herrosé 1863

- New edition 1986 udT Berlin at night. The dark side of a big city. Crime reports . Ed. Paul Thiel. The new Berlin, Berlin (East).

- 1863: Dark houses and streets in London . 2 volumes. Wittenberg: R. Herrosé

- 1865: Dark houses in Paris . Coburg: F. Streit

- 1871: Berlin by night. Cultural images . Berlin: House Friends Expedition

- Individual chapters had already appeared in newspapers years earlier, see, for example, Berlin at night . In: Die Presse (Vienna), No. 250 (September 10, 1865), pp. 1–3 (not paginated); No. 283 (September 23, 1865), pp. 1-3 (not pag.); No. 274 (October 4, 1865), pp. 1-3 (not pag.) - Two dark houses . In: Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), No. 1353 (June 6, 1868), pp. 1–3.

- 1877: Viennese dark houses. A house for the homeless . In: Neue Illustrirte Zeitung (Vienna), V. vol. No. 26 (June 24, 1877), p. 413 f.

- 1877: Viennese dark houses. A rescue house for young girls . In: Neue Illustrirte Zeitung (Vienna), V. vol. No. 27 (July 1, 1877), p. 426 f.

Controversy

- 1860: The Victoria Theater and the intrigues of the theater entrepreneur Cerf . Gustav Bosselmann, Berlin. In addition the counter-writ by Rudolf Cerf : Dispatch of Gustav Rasch . Carl Nöhring, Berlin 1860. New edition of Rasch's brochure in the appendix of: Berlin at night. A selection from the writings of Gustav Rasch with an appendix about the Victoriatheater and the intrigues of the theater entrepreneur Cerf . The new Berlin, Berlin (East) 1986.

- 1863: My answer to the diatribe of the Royal Danish Government "Mr. Gustav Rasch and his brother tribe" . Otto Janke, Berlin. This writing was Rasch's reply to Mr. Gustav Rasch and his brother tribe. From the author of the acts-like contributions to the history of the suffering of the Schleswig clergyman Gustav Schumacher, who was horrified by his office . F. Heinicke, Berlin 1862. The Danish invective was written by Baron Ripperda, a former Prussian officer , at the instigation of ministers Carl Christian Hall and Friedrich Hermann Wolfhagen .

Legal writings

- 1855: The new bankruptcy order together with the law on the introduction of the same, the law on the authority of creditors to contest the legal acts of insolvent debtors outside of bankruptcy and the ordinance of June 4, 1855, on the bankruptcy and inheritance liquidation processes court costs to be levied . A. Sacco, Berlin

- 1856: The house owner and tenant. A practical manual for every landlord and tenant. Berlin

- 1857: The trade legislation of the Prussian state with all related amendments and additional provisions that have been issued to this day . A practical handbook for merchants, manufacturers and traders of all classes presented in a popular and systematic way . Berlin: Hugo Bieler & Co.

- 1861: The lawyer for town and country. Detailed advice for everyone in civil and business dealings, as well as in dealings with administrative and judicial authorities . 3 volumes. A. Dominé

literature

- Anonymous ( Paul Lindau ): Harmless letters from a German small town dweller . First volume. Leipzig: AH Payne 1870 ( Google )

- Friedrich Brockmeyer: The history of the court and the Brockmeyer family to Glane-Visbeck . Obermeyer, Osnabrück 1938 (text as pdf (PDF))

- Bernt Engelmann : Despite all that. German radicals 1777–1977 . C. Bertelsmann, Munich 1977, p. 358 f.

- Florian Greßhake: Germany as a problem for Denmark. The material cultural heritage of the border region Sønderjylland - Schleswig since 1864 . V&R unipress, Göttingen 2013

- J. Günther: "Gustav Rasch and his Tyrolean book". In: Local-Anzeiger der "Presse" (Vienna), supplement to no. 214 (August 6, 1874), p. 7

- Jiří Kořalka : "Two faces of Berlin in modern Czech national consciousness". In: Berlin in modern Europe. A conference report (Ed. W. Ribbe, J. Schmädeke). de Gruyter, Berlin – New York, pp. 275–295, especially p. 278 (on Rasch's Berlin reports for the Prager Zeitung Politik 1870–1871)

- Wojciech Kunicki : Gustav Rasch - without Karl May he would be forgotten . In: Mitteilungen der Karl-May-Gesellschaft 61 (August 1984), pp. 17–24

- Elpis Melena (Marie E. von Schwartz): Garibaldi in Varignano 1862 and on Caprera in October 1863 . Leipzig: Otto Wigand 1864 ( Google )

- Jens Owe Petersen: Schleswig-Holstein 1864–1867. Prussia as the bearer of hope and “grave digger” of the dream of an independent Schleswig-Holstein . Dissertation Kiel 2000 ( pdf (PDF))

- Brigitte von Schönfels: "What you experience is always what you experience yourself". The travel section in German newspapers between the revolution of 1848 and the unification of the empire . Bremen: Edition Lumière 2005, esp.p. 141, 151

- Veit Valentin : History of the German Revolution from 1848–49 , Volume II, Ullstein, Berlin 1931, p. 71.

Web links

- Archives about Gustav Rasch in the Secret State Archive of Prussian Cultural Heritage (1863–1864)

- Karl May Wiki

Individual evidence

- ↑ Date and place of birth as shown in the Rasch profile, which the Braunschweig public prosecutor issued on June 11, 1876.

- ↑ Communications from the trade association for the Kingdom of Hanover . tape 1838–1839 , no. 15-20 . Hanover 1839, p. 71–72 note .

- ↑ a b Brockmeyer 1938, p. 40

- ^ Rasch, A trip to Rügen (1856), p. 4.

- ↑ Valentin 1931, p. 71.

- ^ Wilhelm Blos: The German Revolution. History of the German Movement from 1848 and 1849 . JHW Dietz, Stuttgart 1893, p. 326 note .

- ↑ Colonel Baker's Prison . In: Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt . No. 250 , September 9, 1875, p. 2 .

- ↑ Garibaldi's Memories, based on handwritten records of the same, and based on authentic sources . I-II. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1861.

- ↑ In 1862, Rasch was still in contact with Marie von Schwartz, who reported to him by letter about Garibaldi's health. See the note in the Wiener Morgen-Post , No. 300 of October 31, 1862, p. 2 (not paginated).

- ↑ Melena 1864, p. 310.

- ↑ Melena 1864, p. 142.

- ^ Note sheets: German literature . In: Over land and sea . No. 30 . Stuttgart April 21, 1861, p. 466 .

- ^ The latest German fiction III. In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 1074 . Leipzig January 30, 1864, p. 78 .

- ↑ Press and book trade . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . tape 34 , no. 877 . Leipzig April 21, 1860, p. 290 .

- ↑ (dispatch from Berlin) . In: Tagespost (Morgenblatt) . No. 171 . Graz July 18, 1861, p. 4 (not pag.) .

- ^ Wiener Nachrichten . In: The press . No. 226 . Vienna August 17, 1862, p. 4 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Prohibitions No. XXXIV . In: Austrian bookseller correspondence . No. 26 . Vienna September 10, 1862, p. 221 .

- ↑ Quoted in: Nachrichten aus Wien . In: Strangers Leaf . No. 160 . Vienna June 12, 1863, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ^ Announcements: Bans on printed matter . In: Official Journal of the Wiener Zeitung . No. 133 , June 13, 1863, pp. 767 .

- ↑ Prohibitions . In: Austrian bookseller correspondence . No. 18 . Vienna June 20, 1863, p. 172 .

- ↑ Announcements . In: Official Journal of the Wiener Zeitung . No. 186 , July 29, 1864, p. 167 .

- ↑ Little Chronicle . In: The press. Evening paper . No. 148 , May 30, 1864, pp. 1 (not pag.) .

- ↑ a b A seizure . In: The press. Evening paper . No. 158 , June 9, 1864, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ a b Petersen 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Dispatch from Berlin . In: Strangers Leaf . No. 44 . Vienna February 14, 1863, p. 4 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Features . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 7 & 8 . Berlin February 15, 1863, p. 26 .

- ↑ Quoted in: Denmark: The Revolutionary Army for Schleswig-Holstein . In: The Fatherland. Newspaper for the Austrian monarchy . No. 14 , January 19, 1864, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Denmark. News from Holstein, January 20th . In: The Fatherland. Newspaper for the Austrian monarchy . No. 18 , January 23, 1864, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ^ Dispatch from Flensburg of January 13th . In: The press. Evening paper . tape 47 . Vienna February 16, 1864, p. 1 (not pag.) .

- ^ Correspondence from Flensburg of January 13th . In: Strangers Leaf . No. 48 . Vienna February 17, 1864, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ To the history of the war . In: The press. Evening paper . No. 49 . Vienna February 18, 1864, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ To the history of the war . In: The press. Evening paper . No. 53 . Vienna February 22, 1864, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ The well-known Gustav Rasch . In: The Fatherland. Newspaper for the Austrian monarchy . No. 52 , March 4, 1864, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ From Schleswig-Holstein . In: Wiener Abendpost. Supplement to the Wiener Zeitung . No. 52 , March 4, 1864, p. 210 .

- ↑ Berlin. Process quickly . In: New Free Press. Morning paper . No. 26 . Vienna September 26, 1864, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ a b c Critical indications . In: New Free Press. Evening paper . No. 93 . Vienna December 2, 1864, p. 4 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Little Chronicle . In: New Free Press. Evening paper . No. 162 . Vienna February 10, 1865, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ^ Karl Blind: An Early Aspirant to the German Imperial Crown (With Personal Recollections) . In: The Contemporary Review . 64 (July to December 1893). London 1893, p. 477-491, here p. 489 .

- ↑ Altona. The mood . In: The press . No. 292 . Vienna October 22, 1865, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ^ Opinion reports from Schleswig . In: New stranger sheet. Evening paper . No. 164 . Vienna October 25, 1865, p. 1 .

- ↑ Seizure . In: New Free Press. Morning paper . No. 629 , June 1, 1866, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ See also: History of the Frankfurter Zeitung 1856 to 1906 . Ed .: Verlag der Frankfurter Zeitung. Frankfurt a. M. 1906, p. 296 .

- ↑ Theater, Art and Literature . In: II. Supplement of the new foreign sheet . No. 8 . Vienna January 9, 1870, p. 1 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Little Chronicle . In: The press . No. 106 , April 18, 1865, p. 1 (not pag.) .

- ↑ The newspaper Politik , founded in September 1862 by Jan Stanislav Skrejšovský, had the goal of defending national-Czech interests against the Viennese centralists; Quickly had to feel in good hands there. The newspaper was banned between 1867 and 1869.

- ^ Message about Gustav Rasch . In: Over land and sea . tape XXXI , no. 6 . Stuttgart 1873, p. 106 .

- ↑ Little Chronicle . In: The East. Organ for politics and economics, for science, art and literature . No. 24 . Vienna June 11, 1871, p. 4 .

- ↑ Mixed daily news . In: daily mail. Morning paper . No. 23 . Graz January 29, 1875, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ^ Message about Gustav Rasch . In: Over land and sea . tape XXXIII , no. 9 . Stuttgart 1874, p. 167 .

- ↑ The following proverb has been circulating in German-language publications since at least the 1840s, although it has never been ascribed to a Turkish dervish. In the version "Where the Turk puts his foot, there no more blade of grass grows" it was already in 1846 in the historical-political papers for Catholic Germany (ed. V. Görres & Phillips, Volume 18, p. 67) as a modern Greek proverb quoted. It then appears in this or a similar formulation as a “Greek” or “Oriental” proverb in other writings, see for example Die Moscheen von Saloniki , Illustrirtes Haus- und Familienbuch (Vienna), Jg. 1861, p. 51; H. Wedemer: A trip to the Orient . Regensburg 1877, p. 192; A. Weber: Lectures and speeches . Regensburg 1913, p. 90. Almost identically it was ascribed to an Arabic writer in 1878 in the "German family paper" Die Abendschule (edited by L. Lange, No. 7, October 18, p. 109) in the USA . Sometimes the proverb appeared in a more martial version, for example in a report Peaceful Pictures from the theater of war in Asia Minor . In: The Gazebo . Volume 41, 1855, pp. 548 ( full text [ Wikisource ]). "Where the Turk sets foot there is desert and a breath of death," a man recently called to me who had been traveling for years through European and Asian Turkey ". Unfortunately without a source - but probably from an oriental source - the statement “Wherever the Turk sets foot on the ground, the grass stops growing” is attributed to a Tripolitan, referring to the poor treatment of the Maghrebians by the Turks , see S. Louhichi: The relationship between the Ottoman central power and the province of Tunisia during the 16th and 17th centuries . Diss. Tübingen 2007, p. 154.

- ^ Rasch: The Turks in Europe . tape I , 1873, p. VII .

- ↑ Ignaz Goldziher: Muslim law and its position in the present . In: Pester Lloyd. Morning paper . No. 303 . Budapest October 31, 1916, p. 5–8, here: p. 5 .

- ↑ A Catholic newspaper wrote as early as 1864 that Rasch was “at least not a friend of the Catholic. Church ”, which is why one cannot suspect him of positive bias in matters concerning the Church. See Salzburger Kirchenblatt . No. 47 (November 24, 1864), p. 391.

- ↑ The inhabitants of 'Bocche di Cattaro': the Bay of Kotor on the Montenegrin Adriatic coast.

- ^ Original correspondence from Prague . In: The press . No. 143 . Vienna May 25, 1873, p. 3 .

- ↑ Felix Kanitz: The Kingdom of Serbia and the Serbian People from Roman Times to the Present . Ed .: Bogoljub Jovanović. III: State and society. Bernhard Meyer, Leipzig 1914, p. 357 note 1 .

- ↑ Press and book trade . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 1601 . Leipzig March 7, 1874, p. 175 .

- ^ Correspondence from Braunschweig . In: The press . No. 49 . Vienna February 19, 1876, p. 4 .

- ↑ From the Bavarian border . In: Salzburger Chronik . No. 42 , April 10, 1875, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ^ Correspondence from Lienz . In: Pusterthaler Bote . No. 21 . Bruneck May 22, 1874, p. 82 .

- ^ Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Works . 31 (correspondence October 1864 to December 1867). Dietz, Berlin (East) 1965, p. 318 .

- ^ Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Works . 31 (correspondence October 1864 to December 1867). Dietz, Berlin (East) 1965, p. 554 .

- ↑ Manfred Klim, Richard Sperl (Ed.): Marx Engels Directory . II: letters, postcards, telegrams. Dietz, Berlin 1971, p. 360, 664, 764 .

- ↑ Profile against Dr. Gustav Rasch . In: The press . No. 167 . Vienna June 19, 1876, p. 4 .

- ↑ Profile against Dr. Quickly . In: Fremd-Blatt (morning sheet) . No. 170 . Vienna June 22, 1876, p. 3 f .

- ↑ Daily news . In: Community newspaper . No. 274 . Vienna November 30, 1877, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Daily news . In: Morning Post . No. 47 . Vienna February 17, 1878, p. 3 (not pag.) .

- ↑ From the late Gustav Rasch . In: Morning Post . No. 48 . Vienna February 18, 1878, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ See also: Press and book trade . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . tape 38 , no. 975 . Leipzig March 8, 1862, p. 162 .

- ^ A b Gregor Samarow (= Oscar Meding): Two imperial crowns. Third section of “About sceptres and crowns” . tape 1 . Eduard Hallberger, Stuttgart 1875, p. 66 .

- ↑ The chapter concerning Gustav Rasch in No. 21 (1874), p. 410.

- ↑ Review: From the City of Concils . In: New foreign sheet (Morgenblatt) . No. 50 , February 20, 1870, p. 5 .

- ^ Correspondence from Petersburg . In: The press . No. 40 . Vienna February 10, 1874, p. 5 .

- ↑ To the story of the day . In: Laibacher Tagblatt . No. 288 , December 17, 1874, pp. 2 (not pag.) .

- ^ "As is well known" . In: I. Supplement to the foreigner sheet . No. 71 . Vienna March 12, 1869, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Features. For freedom . In: epoch . No. 126 . Prague May 8, 1879, p. 1 .

- ↑ S. Bor .: "Gorostas which Hajduke" . In: The press . No. 47 . Vienna February 17, 1878, p. 1–3, here p. 1 f .

- ^ A household in Venice . In: East German Post . No. 187 . Vienna July 10, 1866, p. 2 (not pag.) .

- ↑ Anonymous (P. Lindau) 1870, p. 6.

- ↑ Namely the work L'Espagne contemporaine, ses progrès moraux et matériels au XIXe siècle (1862) by Fernando Garrido Tortosa (1821-1883), which the following year in German udT Today's Spain, its intellectual and external development in the 19th century appeared in Leipzig.

- ↑ Anonymous: Harmless letters from a German small town dweller . In: The Salon for Literature, Art and Society . tape IV . Leipzig 1869, p. 111–115, here p. 113 f .

- ↑ Anonymous (P. Lindau) 1870, p. 7 f.

- ↑ The latest failures of the German Reich policy . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 7/8 . Berlin February 15, 1874, p. 26 .

- ↑ New Years Eve and New Years Mornings . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 1 . Berlin January 3, 1875, p. 2 .

- ↑ Technological-philosophical-theological question box . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 6 . Berlin February 7, 1875, p. 23 .

- ↑ On the oriental question . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 41 . Berlin September 5, 1875, p. 162 .

- ↑ (untitled) . In: Kladderadatsch . No. 33 . Berlin July 16, 1876, p. 131 .

- ^ Romania's stories of robbers . In: Garde-Feld-Post 1917 . No. 6 . Berlin February 3, 1917, p. 44 f., here p. 44 .

- ↑ Gerhard Holtz-Baumert: Nothing is sacred here: writers in Berlin, Berlin in literature . The New Berlin, Berlin 2004, p. 229 .

- ↑ A literary interlude . In: The Fatherland. Newspaper for the Austrian monarchy . No. 57 , March 10, 1864, p. 1 (not pag.) .