Sesostris II pyramid

| Sesostris II pyramid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

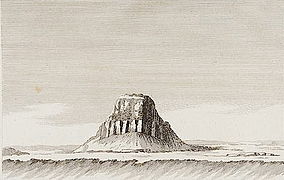

Mud brick core of the Sesostris II pyramid. Parts of the limestone skeleton can be seen on the right.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Sesostris II pyramid of Sesostris II , who was awarded the cultivation of the former swamps of the Fayyum basin in the 12th Dynasty , built his pyramid in Al-Lahun at the entrance of the Bahr Yusuf (Joseph's Canal) in this same area . With a side length of 106 meters and an incline of 42 ° 35 ', it had a height of 48.6 m.

Research history

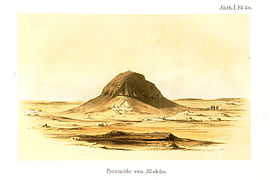

In modern times, the Sesostris II pyramid was first documented by Dominique-Vivant Denon during Napoleon's Egypt expedition 1798-1801. Another documentation of the pyramid was carried out by John Shae Perring in 1839 . The publication took place in 1842 by himself and by Richard William Howard Vyse . Karl Richard Lepsius visited Illahun during his Egypt expedition 1842-1846 and in May 1843 documented the ruins there. He added the Sesostris II pyramid to his list of pyramids under the number LXVI .

The English archaeologist Flinders Petrie carried out the first systematic excavations between 1888 and 1890 . In doing so, he discovered the pyramid city of Kahun, which he excavated over a large area. In the second excavation season, the entrance to the pyramid was discovered and the underground chamber system explored. After turning to other sites for a while, Petrie returned to Illahun in 1914, 1920 and 1921 to carry out further excavations in the vicinity of the pyramid. To this day, Petrie's investigations represent the most important research contribution to the Sesostris II pyramid. Between 1991 and 1997 a team from the Royal Ontario Museum under the direction of Nicholas Millet carried out some small-scale excavations in the pyramid city and on the upper structure of the pyramid.

Surname

A distinctive feature of the 12th Dynasty pyramids is the use of different names for different parts of the pyramid complex. While the facilities of the Old Kingdom only had one name for the entire royal tomb complex, the facilities of the 12th Dynasty had up to four names, which denoted the actual pyramid, the mortuary temple, the cult facilities of the district and the pyramid city. Two names have been recorded for the Sesostris II pyramid. The name of the actual pyramid is unknown. In older literature it was given the name Cha-Senweseret ("Sesostris appears"), which was taken over by Mark Lehner and Miroslav Verner in the 1990s . Dieter Arnold , on the other hand, was able to prove at the end of the 1980s that Cha-Senweseret referred to the pyramid city of the Sesostris I pyramid in Lischt . The district of the Sesostris II pyramid with the mortuary temple and the cult complex was called Sechem-Senweseret ("Sesostris is mighty"). The pyramid city was named Hetep-Senweseret ("Sesostris is at peace").

The pyramid

The superstructure

The core of the pyramid consists of a four-tiered limestone stump , which was provided with a limestone frame, formed from transverse and radial walls. The cavities formed in this limestone skeleton were filled with mud bricks. Mud bricks then also formed the top of the structure.

A surrounding foundation trench carved into the rock formed the basis for the fine limestone cladding of the tomb. In addition, a drainage channel filled with gravel has been installed.

Unfortunately, as with all Egyptian pyramids, the limestone cladding has been removed and burned into fertilizer over the centuries. Without this protective cover, the mud bricks are very susceptible to weathering and so the structure looks crumbling today.

The chamber system

Flinders Petrie spent several months unsuccessfully trying to find the entrance to the pyramid, which should usually be in the north. However, Sesostris II had a different idea for his grave: the entrance was hidden as a 16 m deep shaft outside the pyramid on the southeast corner. This vertical access was much too narrow for the transport of the sarcophagus and the grave goods, so that another construction shaft had to be built, the access of which was later masked by the grave of an unknown princess.

Both shafts are connected by a horizontal corridor that leads to a hall with a vaulted ceiling. At the east end of this hall a vertical shaft leads down and ends in the groundwater.

A rising corridor leads from the hall via another chamber into the southeast area of the interior of the pyramid to an antechamber, which branches off at right angles to the actual burial chamber. The burial chamber is completely lined with granite and has a gable roof. At the west end is the king's sarcophagus made of rose granite, and a small passage leads into an adjoining room. Here Petrie found parts of the burial equipment in the rubble, above all a royal uraeus made of gold, which adorned the ruler's headband and was probably lost by the ancient grave robbers .

Another special feature is a circumferential corridor that branches off between the antechamber and the burial chamber, leads around the burial chamber and flows into it at the head of the sarcophagus. The importance of this passage is still debatable among Egyptologists .

The pyramid district

A thorough inventory of the area around the pyramid has not yet been carried out. So it was only possible to collect a few results from the various excavations. The surrounding wall was decorated with niches in memory of the Djoser pyramid from the 3rd dynasty . The ground plan of the mortuary temple is still unexplored, as is the location of the confluence of the open access road into the pyramid district. The most famous find from the complex is the jewelry of Princess Sithathoriunet , a daughter of the king. The plastered cavity with its five jewelry boxes was overlooked by the ancient grave robbers until Brunton and Petrie examined the grave in 1913.

In addition to these shaft graves for two princesses, eight mastaba graves were located on the north side , each built with mud bricks around a limestone core. In the northeast corner there is a small secondary pyramid with a base dimension of 27.6 m and a former height of about 18 meters. Petrie has searched intensively for a burial chamber here, but unsuccessfully. So it is still unclear whether it was a queen or a cult pyramid .

The pathway has not yet been explored. You know the location of the valley temple , but not its ground plan. However, the discovery of the pyramid city Hetep Senwosret ("Sesostris is satisfied") was of considerable importance . Better known under the name Kahun , an excellent testimony to the ancient Egyptian urban development was discovered here and numerous papyri were found.

See also

literature

General

- Dieter Arnold : The pyramid Sesostris' II. Near El-Lahun. In: Sokar. Volume 32, 2016, pp. 52-65.

- Christian Hölzl : Lahun, pyramid complex of Senusret II. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , p. 429.

- Christian Hölzl (ed.): The pyramids of Egypt. Monuments of Eternity. Brandstätter, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-85498-375-1 , pp. 125–126.

- Mark Lehner : The Secret of the Pyramids in Egypt. Orbis, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-572-01039-X , pp. 175-176.

- Frank Müller-Römer : The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt , Utz 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , p. 216.

- Bertha Porter , Rosalind LB Moss : Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. IV. Lower and Middle Egypt (Delta and Cairo to Asyût). Griffith Institute, Oxford 1968, pp. 107-110 ( PDF; 14.3 MB ).

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 237-241.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 448-454.

Excavation publications

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie : Illahun, Kahun and Gurob. 1889-1890. Nutt, London 1891 ( online version ).

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie, Guy Brunton, Margaret Alice Murray: Lahun II. British School of Archeology in Egypt and Bernard Quaritch, London 1923 ( PDF; 12.9 MB ).

Questions of detail

- Hartwig Altenmüller : The pyramid names of the early 12th dynasty. In: Ulrich Luft (Ed.): The Intellectual Heritage of Egypt. Studies Presented to László Kákosy (= Studia Aegyptiaca. Volume 14). Budapest 1992, ISBN 963-462-542-8 , pp. 33-42 ( online ).

- Felix Arnold : The South Cemeteries of Lisht II. The Control Notes and Team Marks (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 23). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1990, ISBN 978-0-300-09161-8 ( online ).

- Michael Haase : Temples and Gardens. In: Christian Tietze (ed.): Egyptian gardens. Arcus, Weimar 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-034699-6 , pp. 176-201.

- Peter Jánosi : The pyramids of the queens. Investigations into a grave type from the Old and Middle Kingdom. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-7001-2207-1 , pp. 60–62, 120, 176.

- Albert M. Lythgoe : The Treasure of Lahun. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Volume 14, Issue 12/2 1919, pp. 1-28 ( JSTOR 40588558 ).

- Ahmed Bey Kamal : Catalog Général des Antiquités Égyptienne du Musée du Caire. Nos. 23001-23256. Table d'offrandes. Imprimiere de l'Institut Français d'Archeologie Orientale, Cairo 1909 ( online ).

- A. Schwab: The sarcophagi of the Middle Kingdom. A typological study for the 11th to 13th dynasties. Dissertation, Vienna 1989.

- Frank Werner: A world wonder made of Nile mud. Interesting facts about the pyramid Sesostris II. Near Illahun and about the development of the pyramid construction in the Middle Kingdom. In: Sokar. Volume 1, 2000, pp. 20-26.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dominique-Vivant Denon: Voyage dans la basse et la haute Égypte, pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte. Tome I. Peltier, London 1802, pp. 134-136 ( online ).

- ↑ Dominique-Vivant Denon: Voyage dans la basse et la haute Égypte, pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte. Planches. Peltier, London 1802, plate XXVI / 1 ( online ).

- ↑ John Shae Perring, EJ Andrews: The Pyramids of Gizeh. From Actual Survey and Admeasurement. Volume 3, Fraser, London 1843, p. 20, plate 18 ( online ).

- ^ John Shae Perring, Richard William Howard Vyse: Operations carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837: With an Account of a Voyage into Upper Egypt, and Appendix. Volume 3, Fraser, London 1842, pp. 80-82 ( online ).

- ↑ Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. Text. Second volume. Central Egypt with the Faiyum. Edited by Eduard Naville and Ludwig Borchardt, edited by Kurt Sethe. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1904, pp. 7-8 ( online ).

- ^ William Matthew Flinders Petrie: Illahun, Kahun and Gurob. 1891.

- ^ William Matthew Flinders Petrie, Guy Brunton, Margaret Alice Murray: Lahun II. 1923.

- ↑ Royal Ontario Museum ( Memento of the original from April 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Mark Lehner: The secret of the pyramids in Egypt. 1999, p. 17

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. 1999, p. 448.

- ^ Dieter Arnold : The Pyramid of Senwosret I (= Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition. Volume 22). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1988, ISBN 0-87099-506-5 , p. 17 ( online ).

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller: The pyramid names of the early 12th dynasty. 1992, pp. 34-36, 41.

Coordinates: 29 ° 14 ′ 10 ″ N , 30 ° 58 ′ 14 ″ E