Institute for Classical Archeology and Byzantine Archeology

The Institute for Classical Archeology and Byzantine Archeology at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg (until 2004 Archaeological Institute , 2004–2005 Seminar for Classical Archeology , 2005–2019 Institute for Classical Archeology ) is a university institute for Classical and Byzantine Archeology . After archeology was taught in Heidelberg as early as 1804, initially assigned to the department of Classical Philology , the institute was founded in 1866. Led by numerous well-known researchers, it has since developed various focuses in research and teaching and is devoted to a wide range understood understanding of the subject Classical Archeology, for example, the research of the Aegean Bronze Age and Provincial Roman archeology . It is the seat of the corpus of the Minoan and Mycenaean seals and operates the Antiquities Museum of Heidelberg University . About 300 students are currently enrolled. The institute is housed in the college building at the Marstall in Heidelberg's old town .

history

Beginnings of archeology in Heidelberg

Classical archeology at Heidelberg University goes back to the classical philologist Friedrich Creuzer , who was appointed to the university in 1804 and whose special research interest was in Greek mythology . Based on this, he also dealt with other disciplines of Classical Antiquity . For example, he held archaeological lectures throughout his time in Heidelberg, from 1807 in the "Philological-Pedagogical Seminar", which he co-founded, and after it was split up in 1818 in the philological seminar that emerged from it. From 1810 he offered systematic events on archeology every two years, which at that time essentially consisted of the art-historical analysis of Greek art . Although he rarely left the city of Heidelberg, he also played a significant role in the international development of archeology through his correspondence and publications. In addition, Creuzer also dealt with the local early history, so he wrote a work in 1833 with the title "On the history of ancient Roman culture on the Upper Rhine and Neckar" and five years later described in detail a newly excavated Mithraeum from Heidelberg in Rome His private teaching collection of coins and plaster casts was significantly expanded by foundations in 1834 and, as the “Antiquarium Creuzerianum”, formed the basis of the institute's later collection of antiquities .

Creuzer's successor, Karl Zell , was originally a philologist, but when he was appointed in 1846 he was specifically brought to Heidelberg for a “professorship for archeology”. He made a name for himself more as an education politician than as an archaeologist, and from 1848 to 1853 he belonged to the Second Chamber of the Baden Estates Assembly . On February 18, 1848, the Baden government provided him with funds for the procurement of teaching materials for the first time. Also in 1848 he succeeded in having the university library provide space that could be used for the archaeological collection as well as for his lectures. After Zell's retirement in 1855, Karl Bernhard Stark was his successor. For a long time unsuccessfully, he repeatedly applied for fixed and regular funding for archeology until it was granted to him in 1862. Four years later, it was finally possible to found an independent archaeological institute.

Foundation of the institute and development up to the First World War

The establishment of the new institute was a rather formal affair that was carried out without any major celebrations. The year before, a reform of the Philological Seminary had taken place, since archeology no longer played a role there and thus received less support. Their institutional emancipation was therefore more for financial than practical teaching or scientific reasons. By 1868, however, both the archeology department and the holdings of the university library had grown to such an extent that the newly founded institute had to leave its two previous rooms and instead bought the building at 7 Augustinergasse. Now an "institute servant" has also been hired after archeology in Heidelberg had previously consisted exclusively of the respective professor.

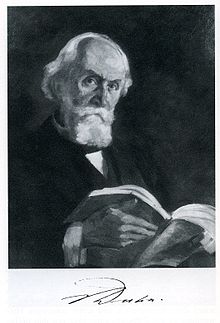

Stark was the last professor who worked intensively beyond today's subject boundaries and, in addition to Roman sites in the Electoral Palatinate, for example, also devoted himself to ancient history and art history in general and took exams in classical philology. His successor Friedrich von Duhn , who worked as a professor in Heidelberg for four decades (1880-1919), on the other hand, no longer had any institutional connection to the neighboring subjects. For these, separate chairs and later institutes were set up (old history 1887 and 1928, modern art history 1893 and 1911).

Von Duhn, like his predecessor, did not lead large excavation projects, as they were often undertaken at the time. Nevertheless, he made long journeys through the Mediterranean, visited excavations of other researchers and dealt with their results. In 1890 he was a participant in the second Troy Conference, at which Heinrich Schliemann presented his successes in finding Troy to the professional world, and supported its localization of the ancient city in today's Hisarlık. At the same time he massively expanded the institute's collection - even while ruthlessly exceeding his (repeatedly increased) budget - in order to keep pace with developments in the subject. Therefore the institute acquired the neighboring houses Schulgasse 2/4 in 1881/1882 and built a skylight hall in the inner courtyard of the building complex for plaster casts of the Parthenon frieze in 1885 on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the university. In addition, von Duhn and his students went on excursions to other collections in Germany and introduced drawing and photography courses in order to impart technical knowledge as a basis for archaeological work. In 1903, in the so-called museum building (which was now called the “Neues Kollegienhaus” and was located on the site of today's New University on Universitätsplatz ), rooms for the Archaeological Institute were vacated, so that the chair moved there and the previous three buildings in Augustiner- and Schulgasse completely could be used for collection. Friedrich von Duhn gained a good international reputation through his work in Heidelberg and built up a large network of former students and other specialist colleagues, which also significantly increased the institute's reputation.

The institute in the time of the world wars

The personnel losses of the Archaeological Institute in the First World War cannot be precisely determined; among other things, three assistants and the institute servant died. Teaching was continued during this time, however, with the general mobilization of the proportion of women among the students rising sharply (after initially increasing only slowly after the admission of women’s studies in 1900). When Friedrich von Duhn retired in 1920, the institute was renowned and well equipped, even if the war had isolated German research internationally. Robert Zahn was chosen as the successor to the chair, and after his rejection the respected archaeologist Ludwig Curtius , who worked in Heidelberg until he was appointed director of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome in 1928. Since the Antikensammlung was meanwhile no longer able to reproduce a representative and contemporary cross-section of the entire archeology, he concentrated more on the establishment of the institute library as well as the photo library and slide collection. In addition, he made a name for himself as the author of popular science books that reached a wide readership for decades.

In 1929, Arnold von Salis was appointed professor at the institute in Curtius' position after Karl Lehmann-Hartleben had represented the chair for a year and Ernst Buschor had preferred an appointment at the University of Munich to Heidelberg. As a neat methodologist who tried to grasp “the inner regularity of [the historical] development” and to take the history of form fully into account, Salis also included artistically simple found objects in research and teaching to a greater extent than his predecessors. However, he had to struggle with various organizational adversities, such as the forced storage of the cast collection in damp basement rooms, which caused the objects to suffer some damage. In 1929 the Kollegienhaus on Universitätsplatz was demolished and the Archaeological Institute moved with other ancient research institutes to the Weinbrennerbau on Marstallhof . In the years after 1933, von Salis, who was Swiss and not a staunch National Socialist, behaved very apolitically in his research. In 1940 he was appointed to the University of Zurich , his position was temporarily replaced by Fritz Schachermeyr in Heidelberg and then by the archaeologist Reinhard Herbig in 1941 .

In some of Herbig's writings, a certain ideological coloring can be demonstrated, as well as in some other institute employees, especially since these were fundamentally checked for system conformity when they were hired. Nevertheless, contrary to the Nazi guidelines, Herbig continued his Etruscan research and in most of the works of the Heidelberg archaeologists and especially in teaching, no direct National Socialist influence can be discerned. In their investigation, Angelos Chaniotis and Ulrich Thaler come to the conclusion that archeology was the only ancient science subject at the university that was “largely spared by National Socialist activists” between 1933 and 1945. The Second World War brought a certain shortage of personnel from 1939 onwards due to the drafting of employees, but until shortly before the end of the war there was no real disruption of research and teaching. When the teaching company reopened in 1946, Herbig was immediately classified as "not burdened".

Development since 1945

After the long-standing caretaker and photographer Anton Heppler was dismissed as a "victim" of the Nazi era in 1946, the institute was able to win over the renowned archeology photographer Hermann Wagner , who remained at the institute until 1961 and also took over caretaker activities until 1953 and also worked as a restorer for metal objects . The first major event after the war was the centenary of the Museum of Antiquities, which opened in 1948 with a special exhibition, a catalog volume (“The World of the Greeks”), a collection of articles on exhibits from the Museum of Antiquities (“Ganymede - Heidelberg Contributions to Ancient Art History”), a series of lectures (published in 1950 under the title “Legacy of Ancient Art”) and a ceremony. Herbig returned the stocks stored during the war to the institute building and created the permanent position of an institute photographer, which was filled with Wagner, who was already employed. In research he was now emphatically apolitical and tried to build on the time before 1933 in teaching, including a large excursion to Italy in 1951. After his appointment as director of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome in 1956, Bernhard Neutsch represented the chair for one and a half years, until Roland Hampe took over the professorship. Under him, the resources were available for a significant expansion of the institute, including the demolition of the wine distillery building and the construction of the new college building in its place, which, in addition to the institute, also housed the cast collection and antique museum from 1971. In 1960, the post of restorer was created for this , and in 1963 that of curator ( Hildegund Gropengiesser until 1992 , Hermann Pflug 1992-2017 ). In 1968 Jörg Schäfer was hired as a lecturer, which gave rise to the institute's second professorship a decade later. Schäfer also dealt with issues that were viewed as marginal, such as ancient ports, and applied new approaches, for example geoarchaeology . In his research, however, Hampe also focused on underdeveloped areas, questions of cultural history and innovative methods. The main focus of his work was the representation of Greek myths (for example, a department of the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae was set up in Heidelberg in 1972 ) and ancient handicrafts, which he intensively investigated in collaboration with the experimental archeologist Adam Winter and other artisans and natural scientists.

After Hampes retired, Tonio Hölscher came to Heidelberg in the 1975 summer semester , where he taught until his retirement in 2010. He took into account very different types of sources from antiquity and used interdisciplinary approaches in order to be able to analyze the political statements and social effects of works of art. This profound examination of ancient objects gave him a high scientific reputation; In 2005 he was awarded the University's Lautenschläger Research Prize. During his tenure, the institute became even more of a (also interdisciplinary) exchange and work location for international researchers. Jörg Schäfer's successor was Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier in 1991 , who continued his focus on the Aegean Bronze Age and was particularly active in the field of excavations. After Niemeier's retirement, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos was appointed to the second chair in 2003, which also focuses on the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. In addition to the professors mentioned, a number of other important researchers worked in Heidelberg, and while Hölscher was absent for research purposes, for example, Luca Giuliani , Alain Schnapp and Barbara Borg took over his duties. In 2002, in the course of the closure of the Archaeological Institute at the University of Mannheim, the professor there, Reinhard Stupperich , was transferred to Heidelberg and a third chair was created for him in Heidelberg, which, however, fell away when Stupperich retired in 2019. In addition to the traditional Greco-Roman focus of classical archeology, he was particularly concerned with the reception of antiquities , the history of archeology and provincial Roman archeology . With him, the editorial staff of Thetis magazine and the Peleus series moved to Heidelberg.

On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the antique collection, a special exhibition in 1998 and an international symposium in 1999 were organized. In 2004 the seminars and institutes for Egyptology , Ancient History and Epigraphy , Christian Archeology , (Classical) Archeology, Papyrology as well as Prehistory and Early History and Near Eastern Archeology merged to form the “Center [until 2005: Institute] for Classical Studies”, whereby the Archaeological Institute changed its name to "Institute [until 2005: Seminar] for Classical Archeology". Since then, the task of managing the institute is no longer the responsibility of the holder of the first chair, but alternates between the professors. As part of the more interdisciplinary orientation, the institute participates in the Cluster of Excellence "Asia and Europe in a Global Context" from 2007 to 2019 , since 2011 in the Collaborative Research Center 933 "Material Text Cultures" and since 2012 in the "Heidelberg Center for Cultural Heritage". Also in 2011 the corpus of the Minoan and Mycenaean seals , which had previously been at the University of Marburg , was transferred to Heidelberg. In the same year the exhibition "The Islands of the Wind" was presented at the institute in collaboration with experimental archaeologists, and has since been shown in several other locations.

After several years in which no successor was found for Tonio Hölscher, who retired in 2010, and the chair was represented by Caterina Maderna , Nikolaus Dietrich was appointed junior professor with tenure track in 2015 . Dietrich's focus is in the field of image science with regard to sculpture from the archaic period and Attic vase painting. In 2015 Maderna, whose fields of work range from ancient sculpture to image and cultural theoretical topics to the reception of antiquities, was also employed as an adjunct professor at the institute.

In 2016, the institute's 150th anniversary was celebrated with a ceremony and honored in an exhibition and an accompanying catalog manual. In 2019 the merger with the Institute for Byzantine Archeology and Art History, the former Christian Archeology, took place to form the new Institute for Classical Archeology and Byzantine Archeology .

Research and Teaching

Thematic focus

The Heidelberg Institute for Classical Archeology has no official specialist focus, but tries to take into account all sub-areas and the various material sources of archeology in the Mediterranean area. Thus, works of art and architecture from antiquity, but also glass objects (through the investigations of Brigitte Borell ) and ancient economic geographic structures (for example in Jörg Schäfer's work) were the subject of research. The archaeological findings and finds should not be examined as an end in themselves, but rather used as a way of illuminating the historical background. In the tradition of Tonio Hölscher, but also of his predecessors, Greek and Roman archeology are not viewed in isolation from one another, but rather in their context.

According to this orientation, the positions at the institute were filled with scientists with very different internal subject orientations: since the creation of a second professorship, the holders of the first chair were archaeologists with a focus on visual and cultural studies with a focus on the classical Greco-Roman period (Tonio Hölscher, Nikolaus Lockpick). The second chair, on the other hand, had already focused on the early Greek period since the appointment of its first holder, Jörg Schäfer, and today it is the only professorship in Germany with a dedicated focus on the Aegean Bronze Age . This epoch had already been intensively researched by Roland Hampe, and Schäfer's successors Niemeier and Panagiotopoulos are also studying the archeology of the Aegean region (which is usually a separate international course). The third chair, which existed for Reinhard Stupperich from 2002 to 2019, had a certain focus on provincial Roman archeology , which, in contrast to many other universities, is not taught as a separate subject at Heidelberg University. The Etruscology as a further addition to discipline of classical archeology since Friedrich von Duhn also in view of the Institute, in addition to Reinhard Herbig especially were associate professors and renowned Etruskologinnen Erika Simon (1958-1964) and Ingrid Krauskopf (2002-2010) working in this field .

Institutional setup and students

The Heidelberg Institute for Classical Archeology aims to work closely with the neighboring subjects, on the one hand with the other archaeological disciplines , on the other hand with the various ancient studies , with which it has formed the "Center for Ancient Studies" since 2004. In detail, for example, there are close contacts with the Institute for Prehistory and Early History and its director Joseph Maran in the field of the Southeast European Bronze Age and with the Seminar for Ancient History and Epigraphy (Director Christian Witschel and previously Géza Alföldy ) on topics including provincial Roman topics. There is also a collaboration with the Institute for Scientific Computing in the field of digital archeology. In addition, the institute is involved in major interdisciplinary research projects such as the Collaborative Research Center 933 “Material Text Cultures” (2011–2019) and the Cluster of Excellence “Asia and Europe in a Global Context” (since 2007).

In addition to the professors, private lecturers and research assistants, there is a restorer position, a conservator position and a photographer position for the specific archaeological work requirements. The number of students in the 2016 summer semester was 211 in the major and 85 in the minor. The library comprises around 63,000 media (as of 2017) and focuses on the Minoan - Mycenaean culture, ancient mythology and religious history, as well as the topography of classical antiquity. There is also a photo library with around 50,000 photo boards and a slide library, which has been reduced to the original photos for reasons of space , since slide projectors have not been used in teaching. In order to support the scientific activities of the institute and to bring it to the public, the circle of friends "Forum Antike" was founded.

Antique museum and cast collection

The antiquities museum and the cast collection, which emerged from the private antiquities collection of the first archeology professor Friedrich Creuzer, were expanded to varying degrees by the various chair holders of the institute, but more or less continuously. After changing rooms several times, they are now housed on the ground floor and on the top floor of the new college building at the Marstall. These rooms are to be significantly enlarged in the course of the renovation of the entire building from 2016.

The collection tries to offer a cross-section of ancient art from the early Mediterranean cultures to the Roman Empire. The antiquities museum mainly shows vases and other clay vessels, but also includes other clay and various bronze objects. The cast collection includes around 15,600 exhibits, making it one of the largest university cast collections in Germany. Around 1,200 casts depict statues, portraits and reliefs, the rest of which are smaller objects such as gems, coins, terra sigillata and seals. There is also a collection of around 5,000 original coins, which is administered by the “Heidelberg Center for Ancient Numismatics”.

Web links

literature

- Friedrich von Duhn : Short list of casts based on ancient sculptures in the archaeological institute of Heidelberg University. 5th edition, J. Hörning, Heidelberg 1907, pp. 1-15 ( online ).

- Roland Hampe : Archaeological Institute. In: Gerhard Hinz (Ed.): 575 years of Ruprecht-Karl University of Heidelberg. From the history of Heidelberg University and its faculties (= Ruperto Carola. Special volume). Brausdruck, Heidelberg 1961, pp. 315-318.

- Hildegund Gropengiesser , Roland Hampe: 125 years of the university's archaeological collections. In: Ruperto Carola. Journal of the Association of Friends of the Student Union of Heidelberg University. Volume 26, Issue 53, August 1974, pp. 31-34.

- Tonio Hölscher : The Archaeological Institute. In: Hans Krabusch (Red.): 600 years of Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. 1386-1986. History, research and teaching. Länderdienst-Verlag, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-87455-044-3 , p. 144 f.

- Angelos Chaniotis , Ulrich Thaler: Classical Studies. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Volker Sellin , Eike Wolgast (Eds.): The University of Heidelberg in National Socialism. Springer Medicine, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 978-3-540-21442-7 , pp. 391-434.

- Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. An exhibition at the University Museum Heidelberg, October 26, 2016 to April 18, 2017. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the following paragraph see Andreas Hensen: Creuzer as a trailblazer in archaeological research. In: Frank Engehausen, Armin Schlechter , Jürgen Paul Schwindt (eds.): Friedrich Creuzer 1771–1858. Philology and Mythology in the Age of Romanticism. Volume accompanying the exhibition in the Heidelberg University Library February 12–8. May 2008 (= Archive and Museum of the University of Heidelberg. Writings. Volume 12). Verlag regionalkultur, Heidelberg et al. 2008, ISBN 978-3-89735-530-9 , pp. 99–111.

- ↑ Friedrich Creuzer: On the history of ancient Roman culture on the Upper Rhine and Neckar. Carl Wilhelm Leske, Leipzig / Darmstadt 1833 ( digitized version ); Friedrich Creuzer: The Mithrēum of Neuenheim near Heidelberg. CF Winter, Heidelberg 1838 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Reinhard Herbig: Foreword. In: The same (ed.): Ganymed. Heidelberg contributions to ancient art history. FH Kerle, Heidelberg 1949, no page number.

- ↑ Gina Frenz: Always tight with cash ...?! The finances of the Institute for Classical Archeology from yesterday to today. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 65–76, here p. 67 f.

- ^ Nicolas Zenzen: The Archaeological Institute in the context of university history. In the S. (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 17–32, here pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Hans Jucker : Arnold von Salis. In: Reinhard Lullies , Wolfgang Schiering (Hrsg.): Archäologenbildnisse . Portraits and short biographies of classical archaeologists in the German language. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-8053-0971-6 , p. 210 f., Here p. 210.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis , Ulrich Thaler: Ancient Studies. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Volker Sellin , Eike Wolgast (Eds.): The University of Heidelberg in National Socialism. Springer Medizin, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 978-3-540-21442-7 , pp. 391-434, here p. 406 and p. 410.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis, Ulrich Thaler: Ancient Studies. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart, Volker Sellin, Eike Wolgast (Eds.): The University of Heidelberg in National Socialism. Springer Medizin, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 978-3-540-21442-7 , pp 391-434, here pp 407 et seq., S. 416, S. 419th

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis, Ulrich Thaler: Ancient Studies. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart, Volker Sellin, Eike Wolgast (Eds.): The University of Heidelberg in National Socialism. Springer Medizin, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 978-3-540-21442-7 , pp. 391-434, here pp. 415 and 420, quotation from p. 406.

- ↑ Bernhard Neutsch (ed.): The world of the Greeks in the picture of the originals of the Heidelberg university collection. Catalog of the anniversary exhibition for the 100th anniversary of the collections of the Archaeological Institute Heidelberg in the summer semester of 1948. FH Kehrle, Heidelberg 1948 ( online ).

- ↑ Reinhard Herbig (Ed.): Ganymed. Heidelberg contributions to ancient art history. FH Kerle, Heidelberg 1949.

- ↑ Reinhard Herbig (ed.): Legacy of ancient art. Guest lectures at the centenary of the Archaeological Collections of Heidelberg University. FH Kehrle, Heidelberg 1950.

- ↑ Not to be confused with the building of the same name on Universitätsplatz, in which the Archaeological Institute was located from 1903 to 1929.

- ↑ Hildegund Gropengiesser , Roland Hampe: 125 years of the university's archaeological collections. In: Ruperto Carola. Journal of the Association of Friends of the Student Union of Heidelberg University. 26th year, issue 53, August 1974, pp. 31–34, here p. 31 f.

- ↑ See also Roland Hampe: From the work of the university institutes: Archäologisches Institut der Universität Heidelberg (activity report from autumn 1957 to spring 1961). In: Heidelberger Jahrbücher. Volume 5, 1961, pp. 143-155, here p. 153.

- ↑ For orientation, a summary of the institute profile on the website of the Institute for Classical Archeology , accessed on November 3, 2016.

- ↑ Verena Müller: 1986–1996: Aegean ceramics and a living institute. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 262–271, here p. 265.

- ↑ Katharina Kroll: 1976–1986: Ancient triumphs and the rejuvenation of classical archeology. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 252–261, here p. 257.

- ↑ Verena Müller: 1986–1996: Aegean ceramics and a living institute. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 262–271, here p. 270.

- ↑ On Etruscology in Heidelberg David Hack: 1946–1956: The Etruscans and a festive rebirth. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 218–228, here pp. 225 f.

- ↑ Nicolas Zenzen: 2016 - and next? Fragments and creative potential. In: Derselbe (Ed.): Objects tell stories (s). 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 294–303, here p. 299.

- ↑ Ourania Stratouli, Nicolas Zenzen: 2006–2016: Seal and the Aegean Sea as an archaeological landscape. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 294–303, here p. 287.

- ↑ On the institute's personal details up to 2016 in detail: Caroline Rödel-Braune: Posten und Personalalien. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 33–64.

- ↑ Nicolas Zenzen: 2016 - and next? Fragments and creative potential. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 294–303, here p. 297.

- ^ Website of the library of the Institute for Classical Archeology , accessed on June 29, 2017.

- ^ Websites of the slide library and the photo library of the Institute for Classical Archeology, accessed on June 29, 2017.

- ^ Website of the Freundeskreis "Forum Antike" , accessed on July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Nicolas Zenzen: 2016 - and next? Fragments and creative potential. In: Nicolas Zenzen (Ed.): Objects tell stories. 150 years of the Institute for Classical Archeology. Institute for Classical Archeology, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-054315-9 , pp. 294–303, here p. 302.