Joseph Carlebach

Joseph Zwi Carlebach (born January 30, 1883 in Lübeck ; died March 26, 1942 in the Biķernieki forest near Riga ) was a German rabbi , scientist and writer.

In December 1941, he and his family were deported to the Jungfernhof camp near Riga (Latvia). After its dissolution, he, his wife and three of his daughters were murdered.

Life

family

Carlebach was the eighth child of Esther Carlebach , a daughter of the local rabbi Alexander Sussmann Adler , who was born in Lübeck , and of the rabbi Salomon Carlebach, who was born in Heidelsheim . The family grave of the Carlebach family is still in the Jewish cemetery in Lübeck-Moisling . In 1919 he married his former student Charlotte Preuss (1900–1942), a niece of the photographer Max Halberstadt . The marriage had nine children, many of whom became rabbis or married a rabbi.

Education and international years

Joseph Carlebach became a rabbi, like most of his brothers, including Ephraim Carlebach , the founder of the Higher Israelite School in Leipzig. Joseph Carlebach also completed a comprehensive scientific education. Like his brothers, he attended the Katharineum in Lübeck , which he graduated from high school at Easter 1901. From 1901 he studied natural sciences, mathematics, astronomy, philosophy and art history in Berlin. The quantum physicist Max Planck and the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey ( hermeneutics ) were among his teachers. In 1908 he completed the senior teacher examination in the natural sciences (with summa cum laude ). Carlebach was trained at the local Orthodox rabbinical seminary at the same time . From 1905 he taught for two years in Palestine at the Jerusalem teachers' college , the Lämel School, and interrupted his studies for this time. There he came into contact with authoritative Torah experts .

In 1909 he graduated from the University of Heidelberg in mathematics, physics and Hebrew. In the same year he received his doctorate as a mathematician (a medieval Talmud scholar) at the University of Heidelberg on the subject of Lewi ben Gerson . The publication of the research work on this scholar, also known as Gersonides, as well as a pioneering work on Einstein's theory of relativity (Berlin 1912) also brought Carlebach academic recognition. From 1910 to 1914, immediately after completing his doctorate, Carlebach devoted himself more to rabbinical studies at the Berlin rabbinical seminary of the Israelite synagogue community Adass Jisroel , which was strictly orthodox and was under the direction of rabbi David Hoffmann . In 1914 he was a rabbi ordained .

From 1914 to 1918, during the First World War , he was drafted into the military. At first he served as a telegraph operator in Mainz . In 1915, on the recommendation of his brother-in-law, the field rabbi Leopold Rosenak , Carlebach was sent to German-occupied Lithuania , which at that time was a center of Jewish learning. He completed his military service as a German cultural officer (with the rank of captain ) and rabbi in Lithuania. In Kaunas , together with local Talmudic scholars , he founded the partly German-speaking Jewish secondary school (zusammenימנזיום עברי), which he also directed until 1919.

Rabbi in Germany

In 1920 Carlebach became the reigning rabbi in Lübeck , until David Alexander Winter followed him there in 1921 .

In 1921 he became rector of the Talmud Tora School in Hamburg. Joseph Carlebach was a creative educator. He responded individually to each student and guided him through his interest in the topic to learn and discover independently. The teacher saw himself as an older friend of the student. The basis and starting point of Carlebach's teaching was the Jewish faith, which should permeate all areas of life and knowledge and guarantee the wholeness and unity of soul and spirit. He saw the aim of the school in the creation of a Jewish environment, supported by the highest Jewish value of moral and ethical responsibility, in which Hebrew is spoken as a living language.

In 1925, Joseph Carlebach was elected as the successor to Chief Rabbi Meir Lerner as Chief Rabbi of the High German Israelite Congregation (HIG) in the then still independent Prussian city of Altona . It was the Altona coat of arms, the symbol of the open gates, that corresponded to it so completely, and Altona's proven acceptance-friendliness not only towards persecuted Jews from Eastern Europe. The then Lord Mayor Max Brauer also welcomed him and remained an enthusiastic visitor to Chief Rabbi Carlebach's lectures for many years. How strongly Carlebach's ideas shaped him became clear when, at the invitation of the American Jewish Congress in mid-March 1936, Brauer gave a speech at a banquet of this association in New York at the invitation of the American Jewish Congress , in which he held anti-Semitism as one of the pillars of the Analyzed Nazi ideology . He also demanded that the struggle of the Jews in Germany against their increasing disenfranchisement must be supported internationally, ideally through a World Jewish Congress.

In 1936, the German-Israelite Congregation (DIG, at that time the Ashkenazi Jewish community of Hamburg ) called Carlebach to the Bornplatz Synagogue in Hamburg as the successor to Chief Rabbi Samuel Spitzer . In front of the assembled crowd he promised in his inaugural address, “(...) that my house and heart will be open to everyone (...) and I will carry all the needs of your soul with you, that I will only honor the vocation to this rabbinical seat as an obligation wants to take to simple humanity towards everyone, that is the promise of this hour (...) ”.

After the incorporation under the Greater Hamburg Act on April 1, 1937, the Jewish communities (German-Israelite community in Hamburg, High German Israelite community in Altona, Israelite community in Wandsbek, Jewish synagogue community in Harburg-Wilhelmsburg) also included Contract for their unification on January 1, 1938. The chosen name Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeinde zu Groß-Hamburg was not approved by the Nazi Ministry of Culture, because "German" is forbidden for Jewish organizations, "Israelitisch" is misleading because in the Nazi racial ideology "Jewish" is the clear term and "community" - so the flimsy argument - is reserved for political communities. The community then chose the name of the Jewish Religious Association in Hamburg . Carlebach remained chief rabbi even after the unification of the communities. In 1937 Bruno Italiener was made chief rabbi of the temple association and in 1938 Carlebach renounced the designation chief rabbi of Hamburg , but instead called himself chief rabbi of the synagogue association .

“The central personality in the life of the Jews in Hamburg-Altona was Chief Rabbi Joseph Carlebach [...]. He embodied the spiritual authority revered and recognized in all directions within the community. Carlebach [...] united the Judaism of East and West in the broadest sense of this word. General culture and Jewish knowledge became an artful synthesis in him, and he was Jewish-Orthodox in his faith and in his way of life. I personally see him standing in front of me as my teacher. "

Harassment in the time of National Socialism

Carlebach's "application for a tax clearance certificate" aroused suspicion that the family wanted to emigrate. The foreign exchange office arranged a security order; after that, Carlebach was only allowed to make payments and withdrawals with official approval via a security account. After the Reichspogromnacht , Jews had to pay a Jewish property tax of 25% of the property to the tax office.

Since October 1940, Carlebach has not received a salary. On May 31, 1941, he was fined for failing to put the compulsory first name Israel in the telephone book. From September 19, 1941, a Star of David had to be worn to stigmatize . With the decree of October 18, 1941, Jews were banned from leaving the country. Gestapo people followed his services. From October 25, 1941, the Jews were deported from Hamburg. The property and property of the deported Jews fell to the Reich in accordance with the 11th ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Act ; the properties were sold through an "asset management office" of the tax office.

Work in the time of National Socialism

Miriam Gillis-Carlebach , the surviving daughter of Joseph Carlebach, remembered her father's commitment to the persecuted Jews during the Nazi era.

Deportation and murder

On December 4, 1941, 753 Hamburg Jews received the deportation order . Because the originally intended destination, the ghetto in Minsk , was overcrowded, the departure was delayed. Fanny Englard born Dominitz, a surviving witness, reported:

“The Gestapo had offered Carlebach to stay behind. But he decided to stay with the transport so as not to disappoint the many people who wanted to travel with him. "

On December 3, the Carlebach family wrote to one of Charlotte's uncle, Siegfried Halberstadt:

“We are about to go east. We want to say goodbye to you once again. We have inner confidence and bless the hour when many fellow travelers feel comforted by us. We wish and implore you and your children all the best. May you stay healthy and happy, be delighted by the happiness of your dear children. All the best!"

Carlebach and his family were deported to the Jungfernhof concentration camp near Riga (Latvia) on December 6, 1941 , where the almost sixty-year-old became seriously ill. In the camp, Carlebach secretly organized school lessons, organized a Hanukkah festival and some bar mitzvah celebrations. When a fellow prisoner refused to eat kosher sausage, he convinced her with the argument that the duty to support the body and life ("Schmirat Haguf") was better served by accepting the energizing food.

On March 26, 1942, Joseph Carlebach, his wife Charlotte and his three youngest daughters Ruth, Noemi and Sara were shot in the forest of Biķernieki near Riga. Only on November 30, 2001, on the occasion of the opening of a memorial at this point, did the cantor of the Jewish community in Riga, Vlad Shulman, speak the kaddish . On the sides of the memorial stone is written in Hebrew, Russian, Latvian and German:

"Oh earth, do not cover my blood, and my screaming will find no rest!"

The youngest son Salomon (Shlomo Peter) survived the tyranny in nine different concentration camps. Carlebach and his wife sent the older five children to safety in England in good time.

progeny

His son, Rabbi Shlomo (Salomon Peter) Carlebach (not to be confused with his eponymous cousin, the singing Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach ) first became a student after the war and later became the mashgiach ruchani ("spiritual director" [of the students]) at the Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin (-Institute) in Brooklyn, New York, a training center for rabbis. His daughter Miriam Gillis-Carlebach , an educationalist, was the director of the Joseph Carlebach Institute for Contemporary Jewish Education at the Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan (Israel). She cultivated contacts with Hamburg, especially the cooperation between the universities.

In memory of Carlebach in Hamburg

In the city of Hamburg and its current Jewish community , the memory of the highly respected Joseph Carlebach is very much cherished:

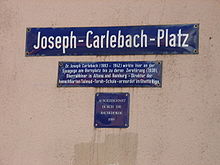

Joseph-Carlebach-Platz

In 1988, the former vaulted ceiling on the former location of the Bornplatz synagogue was recreated in the floor in the original scale using granite stones . Designed according to a design by the artist Margrit Kahl and the architect Bernhard Hirche , the square in Grindel ( Hamburg-Eimsbüttel district ), which is now part of the university campus, was in memory of the last Hamburg chief rabbi before the war in 1990 Renamed Joseph-Carlebach-Platz.

Joseph Carlebach Prize

In 2003, on the 120th birthday of Carlebach, the University of Hamburg founded the Joseph Carlebach Prize, which has been awarded every two years since 2004. The prize is awarded to young academics for outstanding scientific contributions from the Hamburg area to Jewish history, religion and culture. The university wants to make the living Jewish culture and science in Hamburg clearer and better known. The Yiddish language and literature can be studied at the University's Institute for German Studies I.

In 2004, the young researchers Christina Pareigis (Department of Linguistics, Literature and Media Studies) were awarded for their dissertation trogt zikh a gezank - Yiddish song poetry by Kadye Molodovsky, Yitzhak Katzenelson, Mordechaj Gebirtig from the years 1939-1945 and Jorun Poettering (Department of Philosophy and History ) for her master's thesis Hamburg Sefarden in the Atlantic sugar trade of the 17th century .

For the year 2006, at the beginning of 2007, the young scientists Sandra Konrad (Department of Psychology) were invited for their dissertation Everybody has one's own Holocaust. An international study on the effects of the Holocaust on Jewish women of three generations and Christine Müller (Department of Education) for her dissertation on the importance of religion for Jewish youth in Germany .

After two works were awarded at the first two awards, only one work was awarded in 2008/09 and 2010/11:

In 2009 Katharina Kraske received the award for her master's thesis Remember Auschwitz. Representations of the Shoah in Italian literature .

In 2011 Arne Offermanns received an award for his introduction, edition and commentary on The Correspondence Between Ernst Lissauer and Walter A. Berendsohn 1935-1937 .

In 2013 the award was shared again: Dr. Beate Meyer was honored for her monograph Tödliche Gratwanderung - The Reich Association of Jews in Germany between Hope, Coercion, Self-Assertion and Entanglement (1939-1945) , Sebastian Schirrmeister for his master's thesis Das Gastspiel - Friedrich Lobe and the Hebrew Theater 1933-1950 .

In 2015 the award was shared again. The five students Özlem Alagöz-Bakan, Fabian Boehlke, Viktoria Wilke, Nikolas Odinius and Thomas Rost received the prize for their joint seminar paper on the topic of stumbling blocks in the Grindelviertel. From name to biography . The scientist Lea Wohl von Haselberg was also honored for her dissertation And after the Holocaust? Jewish film characters in (West) German film and television after 1945 .

In 2016/17 the award went to Dr. Jutta Braden (Department of History) for her monograph Converts from Judaism in Hamburg 1603 to 1760. Esdras Edzardis Foundation for the Conversion of the Jews from 1667. and to Dr. Inka Le-Huu (also Department of History) for her dissertation The social emancipation of the Jews. Jewish-Christian encounters among the Hamburg bourgeoisie (1830–1871) .

Joseph Carlebach School

For the 2007/08 school year, on August 28, 2007, after 68 years, children again moved into the building of the former Talmud Torah school . School operations begin in the spirit of Joseph Carlebach in the form of a state-approved Jewish all-day elementary school with an attached preschool. The city of Hamburg, the Jewish community and the parents share the financing.

Until then, the college of librarianship was housed in the building. A memorial plaque in the stairwell reminded of the history of the school and the fate of its students and teachers.

The building also houses the kindergarten of the Jewish community with 60 places and the administration of the Jewish community.

In Hamburg-Altona

At the southern end of the Platz der Republik opposite the town hall, the black cube Black Form - Dedicated to the Missing Jews by Sol LeWitt commemorates the Jewish community and its Rabbi Joseph Carlebach with a dedication to the “Jews who are missing from Altona forever”.

In Altona, the Carlebachstrasse , which leads from Gilbertstrasse to Saßstrasse, is a reminder of the Altona chief rabbi.

In Lübeck

The approximately 5.5 hectare Carlebach Park in the new Lübeck university district was named after the Carlebach rabbi family.

Memory of Carlebach in Israel

Joseph Carlebach Institute

The German-speaking academic and educational Joseph Carlebach Institute (JCI), founded in 1992 at the Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan , aims to contribute to German-Jewish and German-Israeli understanding and promotes joint seminars and conferences with German-speaking universities, institutes and student groups. Further goals are the (re) publication of Joseph Carlebach's writings and the maintenance of the memory of the Carlebach family, the Jewish communities and those who perished in the Shoah .

The archive set up by the JCI includes collections on Joseph Carlebach, the Leipzig rabbi Ephraim Carlebach , Jewish life in Schleswig-Holstein and individual documents. The volumes of publications on the Joseph Carlebach Conference, which appear every two to three years, are co-edited by the JCI.

'Rechov Carlebach רחוב קרליבך' in Jerusalem

In the Jerusalem suburb of Talpiot , a street was named after Joseph Carlebach on August 18, 1954 in memory of his work at the Lämel School there.

Works (selection)

- Lewi ben Gerson as a mathematician. A contribution to the history of mathematics among the Jews (dissertation). L. Lamm, Berlin 1910.

- The Song of Songs, translated and interpreted by Joseph Carlebach . Hermon-Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 1924.

- Modern Educational Endeavors and their Relationship to Judaism . Jewish publication series BJA 12 No. 3 (19 pages). Hebrew publishing house “Menorah”, Berlin undated [1924 nor 1925].

-

The three great prophets Isaiah, Jirmiah and Jecheskel; a study (133 pages). Hermon-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1932.

- French translation: Les trois grands prophetes, Isaie, Jeremie, Ezekiel . Traduit de l'allemand par Henri Schilli (141 pp.). Editions A. Michel, Paris 1959.

- The book of Koheleth. An attempt at interpretation . Hermon, Frankfurt am Main 1936.

- Law-abiding Judaism (53 pp.). In Schocken Verlag , Berlin 1936th

- Selected writings , volumes 1 and 2. Edited by Miriam Gillis-Carlebach, with a foreword by Haim H. Cohn. Georg Olms Verlag , Hildesheim, New York 1982.

- Selected Writings , Volume 3. Edited by Miriam Gillis-Carlebach. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2002

- Selected writings , Volume 4: Selected letters from five decades . Edited by Miriam Gillis-Carlebach with the assistance of Gillian Goldmann. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2007

- Mikhtavim mi-Yerushalayim (1905–1906): Erets Yi'sra'el be-reshit ha-me'ah be-`ene moreh tsa`ir, ma'skil-dati mi-Germanyah . Edited and translated by Miryam Gilis-Karlibakh (141 pp., Ill.). Ramat-Gan: Orah, mi-pirsume Mekhon Yosef Karlibakh ; Yerushalayim: Ariel, 1996.

See also

literature

- Biographical lexicon for Schleswig-Holstein and Lübeck . Volume 7, p. 41 ff.

- Sybille Baumbach et al .: "Where roots were ..." Jews in Hamburg-Eimsbüttel 1933 to 1945. Ed. By the Morgenland Gallery, Dölling and Galitz Verlag , Hamburg 1993.

- Andreas Brämer : Joseph Carlebach. Series “Hamburger Köpfe”, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8319-0293-4 .

- Shlomo (Peter) Carlebach: Ish Yehudi - The Life and Legacy of a Torah Great. Joseph Tzvi Carlebach. Shearith Joseph Publications, New York 2008 (English).

- Jens-Peter Finkhäuser, Evelyn Iwersen: The Jews in Altona have long been forgotten. In: Stadtteilarchiv Ottensen eV (ed.): Without us they would not have been able to do that. Nazi era and post-war in Altona and Ottensen. Hamburg 1985.

- Miriam Gillis-Carlebach (ed.): Jewish everyday life as humane resistance. Documents of the Hamburg chief rabbi Dr. Joseph Carlebach from the years 1939–1942. Verlag Verein für Hamburgische Geschichte, Hamburg 1990.

- Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: "Light in the Dark". Jewish lifestyle in the Jungfernhof concentration camp. In: Gerhard Paul and Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: Menorah and swastika. Neumünster 1988, ISBN 3-529-06149-2 , pp. 549-563.

- Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: Every child is my only one. Lotte Carlebach-Preuss. Face of a mother and a rabbi woman. Dölling and Galitz, Hamburg modified new edition 2000, ISBN 3-930802-70-8 .

- Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: “Don't touch my messiahs, they are my school children”. Joseph Carlebach's Jewish education. 2004, ISBN 3-935549-94-6 .

- Carlebach, Joseph. In: Lexicon of German-Jewish Authors . Volume 4: Brech-Carle. Edited by the Bibliographia Judaica archive. Saur, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-598-22684-5 , pp. 436-448.

- Esriel Hildesheimer, Mordechai Eliav: The Berlin Rabbinical Seminar 1873-1938. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-938485460 , pp. 89-90.

- Ulla Hinnenberg / Stadtteilarchiv Ottensen eV: The Jewish cemetery in Ottensen 1582–1992. Hamburg-Altona 1992.

- Ulla Hinnenberg / Stadtteilarchiv Ottensen eV: The Kehille. History and stories of the Altona Jewish community. Hamburg-Altona 1996.

- Alissa Lange: The Jewish retirement home on Grindel. The Jewish history of today's Catholic student residence Franziskus-Kolleg in Hamburg in the 19th century. Hamburg Historical Research, Volume 3, Hamburg University Press, Hamburg 2008.

- Ina Lorenz : The life of Hamburg's Jews under the sign of the “Final Solution” (1942–1945). In: Arno Herzig , Ina Lorenz (Hrsg.): Displacement and extermination of the Jews under National Socialism. Hamburg 1992.

- Ina Lorenz: Go or stay. New beginning of the Jewish community in Hamburg after 1945. Hamburg 2002.

- Ina Lorenz, Jörg Berkemann : Dispute in the Jewish cemetery Ottensen 1663–1993. Two volumes. Hamburg 1995.

- Anthony McElligott: Contested City. Municipal Politics and the Rise of Nazism in Altona 1917–1937. Ann Arbor 1998.

- Beate Meyer: The persecution and murder of Hamburg's Jews 1933–1945. Published by the State Center for Political Education, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-929728-85-0 .

- Jens Michelsen: Jewish life on Wohlers Allee. Hamburg 1995.

- Christine Müller: On the importance of religion for young Jewish people in Germany. Series "Youth - Religion - Classes", Volume 11, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-8309-1763-2 .

- Sabine Niemann (editor): The Carlebachs. A rabbi family from Germany. Ephraim Carlebach Foundation (ed.), Dölling and Galitz, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-926174-99-4 .

- Gerhard Paul , Miriam Gillis-Carlebach (ed.): Menorah and swastika. On the history of the Jews in and from Schleswig-Holstein, Lübeck and Altona (1918–1998). Wacholtz, Neumünster 1998, ISBN 3-529-06149-2 .

- Ursula Randt : The Talmud Tora School in Hamburg 1805-1942. ISBN 3-937904-07-7 .

- Association for research into the history of the Jews in Blankenese eV: Four times life. Jewish fate in Blankenese 1901 to 1943. Hamburg 2003.

- Ursula Wamser, Wilfried Weinke, Ulrich Bauche (eds.): A vanished world: Jewish life on the Grindel. Revised new edition Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-934920-98-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Joseph Carlebach in the catalog of the German National Library

- Joseph Carlebach Institute at the Bar Ilan University in Ramat Gan (Israel)

- Website of the Carlebach Family Archive of the Joseph Carlebach Institute at the Bar Ilan University in Ramat Gan

- Sources about Joseph Carlebach in English

- Dr. Joseph Carlebach * 1883 on the pages of Stolpersteine Hamburg (Author: Andreas Brämer, as of September 2016, accessed on August 8, 2019)

- Joseph Carlebach-Platz and Synagogue Monument ( Memento from September 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- School operations in the Joseph Carlebach School will be resumed , report on abendblatt.de

- Official website of the Joseph Carlebach School

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Genzken: The Abitur graduates of the Katharineum zu Lübeck (grammar school and secondary school) from Easter 1807 to 1907. Borchers, Lübeck 1907. (Supplement to the school program 1907) Digitized No. 1133

- ^ Joseph Carlebach, 'Letter to Leopold Rosenak from May 1917', In: Joseph Carlebach: Selected writings. Part 4: Selected letters from five decades, ed. by Miriam Gillis-Carlebach. Olms, Hildesheim 2007, ISBN 978-3-487-13345-4 , p. 111.

- ↑ On this speech see Axel Schildt: Max Brauer , pp. 63–65 and Christa Fladhammer, Michael Wildt: Introduction , pp. 57–59.

- ^ Biography of Rabbi Carlebach on the website of the Joseph Carlebach Institute

- ^ 'Letter from the Reich and Prussian Minister for Church Affairs to the Hamburg State Office of January 15, 1937' Berlin, Hamburg State Archives, inventory 113-5, EIV B1 file, reproduced from: Four hundred years of Jews in Hamburg: an exhibition by the museum for Hamburg History from November 8, 1991 to March 29, 1992 , Ulrich Bauche (Ed.), Dölling and Galitz, Hamburg 1991, (The History of the Jews in Hamburg; Vol. 1), p. 444, ISBN 3-926174- 31-5

- ^ Andreas Brämer: Judaism and religious reform. The Hamburg Israelitische Tempel 1817-1938. Dölling and Galitz Verlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-933374-78-2 , p. 89

- ↑ Baruch Z. Ophir: On the history of Hamburg's Jews 1919-1939 . In: Peter Freimark (ed.): Jews in Prussia - Jews in Hamburg . Hamburg Contributions to the History of German Jews , Vol. 10. Institute for the History of German Jews / Hans Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1983 ( PDF, 54 MB ), p. 94

- ↑ Hans-Juergen Fink: The acts of evil. In: Hamburger Abendblatt dated June 11, 2011, p. 12 , (Sources for Fink's article: Summary of an interview with Miriam Gillis-Carlebach and files on criminal proceedings and financial investigations from the State Archives of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg )

- ↑ Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: "Light in the Dark". Jewish lifestyle in the Jungfernhof concentration camp. In: Gerhard Paul and Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: Menorah and swastika. Neumünster 1988, ISBN 3-529-06149-2 , p. 551

- ↑ according to Gillis-Carlebach, Jewish everyday life as human resistance, p. 109

- ↑ Miriam Gillis-Carlebach: "Light in the Darkness" ... ISBN 3-529-06149-2 , p. 560.

- ^ Joseph Carlebach Prize on the website of the University of Hamburg

- ↑ Joseph Carlebach Prize this time awarded to two researchers , Kieler Nachrichten online , April 22, 2013

- ^ Tenth International Joseph Carlebach Conference and Joseph Carlebach Prize 2015 , press release of the University of Hamburg , April 20, 2015, accessed on March 6, 2018

- ↑ Carlebachstrasse ( Memento from March 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), in: eins A. District newspaper for the Altona-Altstadt development quarter , May 2012, p. 3

- ↑ Via the Joseph Carlebach Institute on the website of the German Jewish Cultural Heritage (GJCH) project at the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies e. V. at the University of Potsdam

- ↑ Announcement Volume 3 on the website of Georg Olms Verlag

- ↑ Announcement Volume 4 on the website of Georg Olms Verlag

- ↑ Information on the publication on the website of the University of Hamburg publishing house

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Carlebach, Joseph |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Carlebach, Joseph Zwi |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German rabbi, victim of the Holocaust |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 30, 1883 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lübeck |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 26, 1942 |

| Place of death | near Riga |