Judaism in Munster

The Judaism in Münster (Westphalia) looks back on a more than 800-year-old varied history and is one of the oldest north-west Germany.

Already in the 12th century there was a Jewish community with its own prayer house in Münster , which was destroyed by pogroms in 1350 . From 1536 onwards Jews settled again who were under the protection of the bishop , but who could not avoid expulsion after his death in 1553. Until the 19th century there was no Jewish community in Münster. From 1616, however, there was a pass system that precisely regulated the entry requirements for Jews. In 1662 the prince-bishop issued the Münster Jewish code . Since then, a so-called court Jew was active in Münster, who represented the interests of the minority in the monastery of Münster , but - himself an instrument of absolutism - could not enforce a permanent right to stay in the cathedral city.

Only in 1810 did the resettlement of Jewish citizens begin, who fought for their legal emancipation in Prussia during the 19th century . An important spokesman for Reform Judaism , Alexander Haindorf , worked in Münster and founded the Jewish- humanist school of the Marks-Haindorf Foundation there . During the time of the Empire and the Weimar Republic Jewish personalities left the public life of the city with much before in the era of National Socialism first the synagogue in 1938 went up in flames and in the following years the Jewish population cathedral in the Holocaust was persecuted and murdered.

Nevertheless, after the Second World War and the collapse of the Nazi regime, the Jewish community was able to revive and a new synagogue was consecrated as early as 1961. In 2018 the community had 589 members and was once again part of the image of the city. She is a member of the regional association of the Jewish communities of Westphalia-Lippe .

history

Beginnings

The first Jewish traveler to visit Münster was Juda ben David HaLewi from Cologne . In total, he stayed in Munster for twenty weeks while he waited to get back money borrowed from Bishop Egbert (1127–1132). In the course of the 12th century, Jews finally settled in Münster. After the city was expanded in 1173, the growing community was able to build its own synagogue, a mikveh and a sales point for kosher meat ( schochet ). The Jewish institutions were located in preferred locations in the city center, near the town hall , on today's Syndikatsplatz. The settlers who came to Munster came mainly from the Rhineland . At the time of Bishop Everhard von Diest , the first persecution of Jews in the city took place in 1287 for an unknown reason . 90 people fell victim to it. Under Prince-Bishop Ludwig II of Hesse (1310-1358) their influx intensified.

The oldest surviving Jewish tombstone in Westphalia comes from the cathedral from 1324. It comes from a Jewish cemetery that was on the school grounds of today's Paulinum grammar school . This was leveled after the pogrom after the plague wave in 1350. The memorial stone is now in the synagogue of the Jewish community in Münster , after it was in the newer Jewish cemetery .

A rabbi was already active in the city in the 14th century . However, as early as 1350, the first Jewish community was destroyed in the pogroms of the plague , when the Christian urban population associated the minority with the spreading plague and forcibly expelled them from the city. For more than a hundred years, Jewish life in Münster died out.

Under Bishop Franz von Waldeck

After the end of the Anabaptist rule , Bishop Franz von Waldeck gave at least ten Jewish families the right to stay in the cathedral city in 1536. The reasons were economic: The bishop was concerned with the Jews as financiers and taxpayers. This generation of Jewish settlers came from Waldeck , the home of the bishop. However, a fully equipped church did not emerge again. The old Jewish institutions and the area behind the town hall could not be revived, the settlers moved to the outskirts of the city. Their living conditions reflected the changed social position: they belonged to the petty bourgeoisie, the days of the Jewish credit system were over. After the end of the Anabaptist rule, the city, which had been granted full rights by the empire again in 1541, prevented the influx of further Jews. In 1553 the guilds were finally reunified , in which the Jewish population group could not participate and which was thus further isolated. The only protection against pogroms was offered by Bishop Franz von Waldeck, who supported the community until his death in July 1553.

Only six months later, however, the council decided to expel the Jews. Most left the city by the end of 1554 and settled in rural Münsterland . Only Jakob von Korbach , who had medical knowledge, received a right of residence under strict conditions. The Jewish community of Münster ceased to exist from 1554 until the beginning of the 19th century. Jews in Münster were denied permanent right to stay for almost three centuries.

Between expulsion and the Thirty Years' War

In 1560, the assembly of the estates decided to expel all Jews from the bishopric of Münster . Because of different interests among the estates, this edict was not enforced. Many Jewish communities continued to grow in the Münsterland. Although the Reichstag had stipulated in 1551 that Jews could take part in markets, a Jewish broadcast visitor from Hamm was arrested in 1603 . Only Jewish doctors, such as Hertz von Warendorf , who stayed in Münster for over six months at the beginning of the 17th century and treated episcopal officials, were the only things that the council met with less suspicion . Due to the increasing number of Jews seeking admission, the Münster city administration introduced a system of passes in 1616, which was modified in 1620 and 1621. The city secretary was obliged to enter names and length of stay and to collect passport fees. The income from the so-called Jewish escort contributed only to a small extent to the city's finances.

Between Peace of Westphalia and emancipation

After the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 the heyday of absolutism began , which pursued a new policy towards the Jews. In 1662, Prince-Bishop Christoph Bernhard von Galen (1650–1678) issued an ordinance on Jews . It described in great detail the rights and duties of the Jews in the monastery. Since 1551 the Münster Jews were under the protection of the "commander and predecessor" who worked as spokesman for the collegiate Jews for the prince-bishop. This proxy functioned as an episcopal tool and was called a court Jew . For the communities this meant pressure on the internal Jewish order. Many pushed out of traditional occupations, such as money lending , and into the cattle trade. Between 1720 and 1795 the number of Jewish families in the bishopric of Münster multiplied from 75 to 203. This also affected the cathedral city, which still did not grant Jews permanent right to stay. In 1765, Elector Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels said that there were "a considerable number of foreign and local Jews" in Münster.

In 1765 the council allowed Jewish cattle and horse traders to move into hostels in Münster other than the five inns specially designed for Jews. In the middle of the 18th century, more Jews converted to Christianity than before. At the same time, the estates, the main opponent of the Jews, accused the travelers of illegally using the Nagelschen Hof as a Jewish place of worship. In 1768 Maximilian Friedrich even had to intervene against the anti-Semitic riots in the population and strengthen his protection. The already negative image of Jews among Christians was made worse by the participation of Jewish robber gangs in numerous criminal cases. The anti-Jewish guilds, who spoke of a “Jewish danger” in 1770, were faced with enlightened higher officials of the monastery. In 1771 the first land rabbi to reside in the diocese, Michael Meyer Breslauer , took up the service as court Jew. However, a decisive change in the situation of the community did not occur until from 1807, when Munster at the Napoleonic -bestimmten Grand Duchy of Berg was one. As Minister of the Interior, Johann Franz Joseph von Nesselrode-Reichenstein enforced the rights of Jews in the Grand Duchy. On February 13, 1810, Nathan Elias Metz from Warendorf was the first Jew since 1554 to receive a permanent residence permit. Another 80 naturalizations followed by September 1816. In 1811 a new Jewish cemetery was built, which is still in use today.

Struggle for emancipation

In the Peace of Paris in 1814, Münster fell to Prussia . Since April 30, 1815 it was the capital of the new province of Westphalia . Three years earlier, in 1812, Karl August von Hardenberg had enforced the legal emancipation of the Jews in the kingdom with the so-called Jewish edict and made them - under certain restrictions - Prussian citizens. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, however, the government in Berlin declared that the law would not yet be implemented in the new, western provinces. Even the Jewish-friendly first Upper President of Westphalia, Ludwig von Vincke , could not prevent the civil rights setback . At the same time, a fundamental discourse began in German Jewry: there were disputes between orthodoxy and the progressive reform movement . These two main directions had prominent spokesmen in Münster as well: the regional rabbi Abraham Sutro (1784–1869) and the physician and humanist Alexander Haindorf (1782–1862) were ideologically opposed. Haindorf, himself the first Jewish professor at the University of Münster , spoke of an " amalgamation of Christianity and Judaism", an assimilation in mutual benefit and respect for cultures, while emancipation was just a legal matter for Sutro. In Munster, the reformer party around Haindorf proved to be stronger.

With the help of the Oberpräsident von Vincke, Haindorf was able to set up the Marks Haindorf Foundation in 1825 . The foundation ran its own school and promoted handicrafts among the Jewish population. Thanks to the Marks-Haindorf Foundation's teachers' seminar, this establishment radiated from Münster to the whole of Prussia: As the leading educational institution for Reform Judaism in the western provinces, it offered students particularly good opportunities. The Marks-Haindorf-Stiftung was an important pillar of Judaism in Westphalia up to the time of National Socialism. In addition to the high standards of the school, the principles of humanity, practical tolerance and Prussian patriotism also contributed to the institution's good reputation.

In 1846 the district government enforced the final acceptance of family names among Jews. At this point in time, all Jewish citizens of Münster had already unofficially adopted family names. In the Prussian constitution of 1848 the legal equality was accomplished. The conservative politics after the failed revolution of 1848/1849 delayed the full social emancipation again. The number of Jews in Münster rose significantly in the 1850s: in 1858 it reached its highest share of 1% of the total population of Münster (312 of 29,992 inhabitants). Than during the industrialization of liberalism was ascendant, raised in 1869, the law concerning the equality of denominations in civil and political relationship "all existing, derived from the diversity of religious beliefs restrictions" on. This also applied to the Jewish population in Münster, which was now formally equal.

Empire and Weimar Republic

In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, Jewish soldiers also fought on the German side. The economically successful period after the war was won was followed by the Founders' Crash of 1873. When looking for those responsible, it was believed that they had found them in the Jews, which was further encouraged by the envy of their rapid social advancement during the Gründerzeit . It was in this situation that modern anti-Semitism emerged . At the same time, the number of Jewish citizens in Münster grew from 81 to 580 between 1825 and 1925, which is why the prayer house built in 1830 on Loerstraße soon no longer offered sufficient space. Due to the rapid growth of the entire city, however, the proportion of Jews only made up an average of half a percentage point of the Münster population. In any case, Westphalia and Munster were below the Prussian and German averages with their share of Jewish populations. Here, too, their professions changed: more and more Jews were active as doctors, lawyers and merchants. The members of the Flechtheim family, owners of the grain and wool business M. Flechtheim & Comp, made special contributions to the expansion of Münster's economy and infrastructure . and builder of the Flechtheim store .

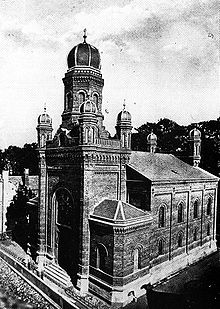

Under the direction of Moritz Meier Spanier , the importance of the Marks Haindorf Foundation reached its peak. He emphasized the deep ties of the Jews with Germany and rejected the emerging Zionism . An expert opinion from 1905 stated: “The seminarians are brought up in and to national and patriotic sentiments.” With the inauguration of the large, representative synagogue on August 27, 1880, the Jewish community came into the focus of the city's public. The building was located directly on the promenade and also reflected the increased prosperity of the Jews. Eli Marcus , who belonged to the Jewish community and had an education at the Marks-Haindorf Foundation, was one of the most popular dialect poets in the Münsterland around 1900 and was a regional celebrity. The Zoological evening party of Hermann Landois ensured a growing interest of Münster.

The anti-Semite August Rohling , who worked as a professor of theology at the university, also caused a stir . With his inflammatory pamphlet Der Talmudjude , which appeared in numerous editions until 1924 and in some cases was even distributed free of charge, he incited the people of Münster against the Jewish minority. When, in 1884, an excerpt from the book Judenspiegel , which came from Rohling's immediate environment, appeared in the Westphalian Merkur , even the Prussian public prosecutor had to intervene for insulting a state-recognized religious community.

The Jews placed great hopes in the civil peace policy at the beginning of the First World War , which tried to bridge the differences between social groups and creeds. A total of 15 Jews from Münster lost their lives in the First World War. During the Weimar Republic , the Jewish community became closer to the Center Party , which had an absolute majority in Münster. In Münsterland, Jewish local politicians ran for elections for the Center Party and in Münster, too, the liberal-conservative Jewish educated middle class opened up to the Center, while this party slowly accepted citizens of other denominations in its ranks. In particular, the common opposition to left or right-wing extremist groups, especially that of the emerging National Socialism , intensified this process.

In 1918 the first Jewish student union, Rheno Bavaria , was established in Münster, to which 51 students belonged a year later. A second connection, the connection between Jewish students, existed from 1920 to 1921. There had already been Jewish students at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität during the German Empire, but only at the beginning of the Weimar Republic did Jewish professors return to Münster - the first since Alexander Haindorf. Among others, the mathematician Leon Lichtenstein , the archaeologist Karl Lehmann-Hartleben and the historian Friedrich Münzer taught in Münster . All Jewish professors lost their posts during the Nazi era.

time of the nationalsocialism

In 1933, at the beginning of the National Socialist era , around 700 Jews lived in Münster. The first major anti-Semitic action by the NSDAP was the so-called Jewish boycott , which also affected numerous shops, law firms and medical practices in Münster. Soon afterwards, the Law on Professional Civil Servants prohibited Jewish professors from entering the university, and Jewish lawyers were no longer allowed to enter the courthouse after the introduction of the Law on Admission to the Bar . In 1935 the Nuremberg Laws stipulated that citizens of the Reich were only those who were "German or related blood". From then on, ancestry decided about life and death; it was precisely defined who was a “ Jewish mixed race ”. This legislation also affected Jewish Münsteraner. For example, the National Socialist propaganda paper Der Stürmer explicitly denounced a Christian-Jewish marriage from Münster as a race disgrace .

The third wave of anti-Semitism after 1933 and 1935 began in 1938 and reached its sad climax with the November pogroms . During the Reichspogromnacht from November 9th to 10th 1938, over 1,400 synagogues, prayer rooms and other meeting rooms burned in Germany. Thousands of shops, homes and Jewish cemeteries were destroyed. The rulers used the attack by the Polish Jew Herschel Grynszpan on the German Legation Councilor Ernst Eduard vom Rath as an occasion and pretext . As everywhere in Germany, this attack was used in Münster for a press campaign against the “anti-German conspiracy of international Jewry”. The processes in Münster were similar to those in the rest of the German Empire: the synagogue was set on fire, Jewish business buildings were devastated and individual Jews were attacked. By this time, 264 Munster Jews had already left their homeland and emigrated abroad.

With the law on tenancy agreements with Jews of April 30, 1939, tenant protection for Jews was abolished. In implementation, this meant that Jewish tenants could be given notice without notice and they were then forcibly moved together in so-called Jewish houses . There were seven such houses in Münster. From September 1, 1941, all Jews over the age of 6 must wear the Star of David in order to publicly brand them. The first deportation of Jews from Münster took place on December 13, 1941 : at least 135 members of the community were deported to the Riga ghetto and murdered there a little later. From February 4, 1942, the Nazi police gathered all Jews who remained in Münster in the building of the Marks-Haindorf Foundation at Kanonengraben 4. A second deportation from Münster took place in July 1942, the third finally in March 1943 to Auschwitz . The school director of the Marks Haindorf Foundation, Julius Voos , also died there. The rabbi of the Münster community, Fritz Leopold Steinthal , emigrated to Argentina in time and thus survived the Shoah .

Of the originally 708 members of the Jewish community in 1933, 275 were murdered in concentration camps. A total of 280 Jewish citizens left Münster and emigrated abroad, seven committed suicide and four survived National Socialism in Münster underground. After deducting the 77 people who died of natural causes during this period, there are 42 people whose fate remains unclear. With the last deportation in March 1943, Münster was declared “ Jew-free ”. The Jewish community had ceased to exist.

New beginning after 1945

After the collapse of the “ Third Reich ”, few Jews returned to the Münsterland, above all Siegfried Goldenberg and Hugo Spiegel . They wanted to make contact with the few survivors of the Holocaust . At the time, nobody believed in a revival of church life in Germany. But the first service with 28 believers after the Holocaust took place in Warendorf on September 7th. The synagogue in Warendorf continued to be used jointly until 1947, before 23 Jews lived in Münster again, who were able to celebrate services in Siegfried Goldenberg's private apartment.

In 1949 the Marks-Haindorf Foundation was rebuilt, which from then on served as the new community center. Around 1960 the number of parishioners was around 130 people. Regular church services, religious instruction and community celebrations could take place again. The community decided to build a new community center on the ancestral site of the destroyed old synagogue. On March 12, 1961, the new synagogue was consecrated and given its function.

Todays situation

The Jewish community in Münster today has around 630 members again. After the Holocaust had significantly reduced the number of members, the influx of large numbers of Jewish people from the former Soviet Union represented a major turnaround. Almost 96% of the community members come from the successor states of the Soviet Union . Many of the new members from the CIS countries came to Münster, among other things, because they had to escape anti-Semitic riots in their homeland, so that for many of them the Münsterland became the destination and place of their refuge. The board of directors of the Jewish community first had to be prepared for the fact that a Jewish religious background and basic knowledge of Jewish traditions were not to be expected for granted, on the one hand, and the new members from the CIS states needed the Jewish community necessary and yet differently than in the traditional sense, on the other hand . They took and still take the Jewish community as a stop and a new home, as a service and cultural institution, as a meeting place where like-minded people, friends and acquaintances can meet, deal with the Jewish religion and also gain a foothold in a completely new system. This situation presented a great challenge, as the new members were supposed to integrate themselves in two ways: on the one hand as Eastern Europeans in Germany and on the other hand as Jews in the Jewish community. In the Soviet Union, the practice of religion was also subject to government restrictions for decades.

The Jewish community helped its new members from the CIS states with the search for housing, for children, for school and training places as well as with the search for a possible job. Thanks to the large increase in members, full services can now be celebrated again for all church services and Jewish holidays. In addition to regular, public schooling, Jewish children and young people also receive Jewish religious instruction from a state-approved religious teacher. The Jewish community life in Münster is very active again today: In addition to the senior citizens' club, the women's association and the choir, there is also the Ha Tikwa youth center , its own library and a functioning social work department. The community has a Chewra Kadisha .

The Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation , founded in 1957, now has around 600 members in Münster. Thanks to numerous events organized by society and the community, such as the annual Jewish Culture Week , Judaism is once again firmly established in public life in the city of Münster. The city partnership with Rishon-Le-Zion in Israel has also contributed to this since 1981 .

On Sunday, October 28, 2012, the Münster Jewish Community was able to inaugurate a successful, barrier-free renovation and extension of the Jewish Community Center after a construction period of almost 6 months. The public was invited. By the evening the Jewish community had well over a thousand visitors. The expansion of the community center was urgently needed after the Jewish community of Münster had grown significantly in recent years, as neither the community leadership nor the city of Münster would have dared to hope after the Hitler fascism of 1933–1945.

Further literature

- Diethard Aschoff: The Jews in Westphalia between the Black Death and the Reformation (1350–1530) , in: Westfälische Forschungen 30 , Münster 1980. P. 78–106.

- Diethard Aschoff: Original story - using the example of the city of Münster 5 - The Jews . Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster 1981.

- Diethard Aschoff: Sources and regesta on the history of the Jews in the city of Münster: 1530–1650 / 1662 (Westfalia Judaica vol. 3,1). Münster 2000, ISBN 3-8258-3440-9 .

- B. Brilling: Judaism in the Province of Westphalia 1815–1945 , in: Publications of the Historical Commission for Westphalia 38, Münster 1918, pp. 105–143.

- Susanne Freund: Jewish educational history between emancipation and exclusion - the example of the Marks-Haindorf Foundation in Münster (1825–1942) . Verlag Schöningh. Münster u. Paderborn 1997, ISBN 3-506-79595-3 .

- A. Herzig: Judaism and emancipation in Westphalia . Munster 1978.

- Gisela Möllenhoff and Rita Schlautmann-Overmeyer: Jewish families in Münster 1918–1945 . Part 2.1: Treatises and documents 1918–1935. Verlag Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster 1998.

- Remembrance and a new beginning / The Jewish community of Münster after 1945 / A self-portrait / Sharon Fehr (Ed.). with the collaboration of Iris Nölle Hornkamp and Julius Voloj / mentis Verlag.

Movies

- Between hope and fear. Jewish fates in the minster during the Nazi era. DVD with booklet, ed. from the LWL media center for Westphalia, Münster 2010 ( PDF version of the booklet )

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jewish community Münster Kdö.R. In: Zentralratderjuden.de. Central Council of Jews in Germany Kdö.R., accessed on November 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Wilhelm Kohl: The dioceses of the church province Cologne . The diocese of Münster 7.3: The diocese. Berlin 2003 (Germania Sacra NF. Vol. 37,3), ISBN 978-3-11-017592-9 , p. 355 Partial digitization

- ^ Andreas Jordan: The Jewish cemetery culture. In: gelsenzentrum.de. October 2007, accessed November 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Westfälische Nachrichten : Graves under the Paulinum: the school grounds once housed the Jewish cemetery - students remember it , Münster, Karin Völker, February 6, 2015

- ^ Marie-Theres Wacker: History of the Jewish cemetery on Einsteinstrasse. In: juedischer-friedhof-muenster.de. Association for the Promotion of the Jewish Cemetery on Einsteinstrasse. Münster e. V., accessed on November 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Thomas Deibert, Birgit Seggewiß: A student project on remembrance culture at the Paulinum grammar school in Münster: memorial stone for the former Jewish cemetery. In: juedischer-friedhof-muenster.de. Association for the Promotion of the Jewish Cemetery on Einsteinstrasse. Münster e. V., accessed on November 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Aschoff, Geschichte Original , p. 6.

- ↑ M. Lahrkamp: Münster in Napoleonic times 1800–1815 , in: Sources and research on the history of the city of Münster, NF 7./8. (1976), pp. 552-553.

- ↑ B. Brilling: Judaism in the Province of Westphalia 1815-1945 , in: Publications of the Historical Commission for Westphalia 38. Münster 1978, p. 117.

- ↑ See Susanne Freund: Jewish educational history between emancipation and exclusion - the example of the Marks-Haindorf Foundation in Münster (1825–1942) . Verlag Schöningh. Münster u. Paderborn 1997, ISBN 3-506-79595-3 .

- ↑ a b c d Aschoff, p. 9.

- ↑ A. Herzig: Judaism and Emancipation in Westphalia . Münster 1973. pp. 63-65.

- ↑ The Jewish fallen soldiers of the German Army, the German Navy and the German Schutztruppen 1914–1918 . Published by the Reich Association of Jewish Front Soldiers , Berlin 1932. p. 294.

- ↑ See K. von Figura and K. Ulrich: Kristallnacht in Münster . Prehistory, events and consequences of November 9, 1938, in: Westfälische Nachrichten and Münsterische Zeitung, November 4 to 16, 1978.

- ^ Martin Kalitschke: 80 years ago: Reichspogromnacht in Münster. The night all hell broke loose. In: Westfälische Nachrichten. November 9, 2018, accessed November 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Aschoff, p. 10.

Coordinates: 51 ° 57 '33.9 " N , 7 ° 37' 54.9" E