Buggingen potash salt mine

| Buggingen potash salt mine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

| Ensemble with restored sheave of the headframe of the former “Rudolphe” potash mine in neighboring Ungersheim ( Alsace ), since autumn 2013 at the western entrance to Buggingen. | |||

| Mining technology | Civil engineering | ||

| Funding / total | 17,000,000 t | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | Kali und Salz AG | ||

| Employees | 1200 | ||

| Start of operation | 1922 | ||

| End of operation | April 30, 1973 | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Potash / rock salt | ||

| Potash salt | |||

| Buggingen | |||

| Mightiness | 4.5 m | ||

| Raw material content | 28% | ||

| Greatest depth | 786 m | ||

| overall length | 10,000 m | ||

| Rock salt | |||

| Degradation of | Rock salt | ||

| Buggingen | |||

| Mightiness | 1 m | ||

| Raw material content | 48% | ||

| Greatest depth | 786 m | ||

| overall length | 10,000 m | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 47 ° 51 '22.3 " N , 7 ° 37' 16.1" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | At the potash shaft | ||

| local community | Buggingen | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Breisgau-Upper Black Forest | ||

| country | State of Baden-Württemberg | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

The Buggingen potash salt mine in Buggingen in the Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald district was the largest mine in southern Germany. It existed from 1922 to 1973. With up to 1,200 employees, it was a major employer in the region.

One ton of raw salt extracted contained 28% potash salt and 48% rock salt . The plant produced a total of 17 million tons of crude salt. The potash was processed into fertilizers in its own factory , and bromine and road salt were produced. The last owner was Kali und Salz AG , based in Kassel .

history

Start of potash mining

In 1904 potash was found by deep drilling near Mulhouse . This created the potash district in Alsace on the left bank of the Rhine . In 1910, the Berlin banker Fritz Eltzbacher received the concession to search for salt deposits on the Baden side of the Rhine. In the years 1911 to 1913, holes were drilled in the “Breitlache”, “Hölzleeck” and “Ob dem Mühlengraben” basins near Buggingen. At Hartheim (10 km north of Buggingen) a first deep well that began on March 2, 1911, was canceled at 1143 m. In the Buggingen 1 deep borehole west of the station, which began on January 11, 1912, a 4 m thick potash deposit was drilled at a depth of 712 m . A drilling in the "Kuntel" was unsuccessful. The salts encountered were among the most valuable potash salts known at the time.

After these preliminary investigations, lengthy negotiations for the establishment of the mine followed, as many property owners initially refused to sell their property. When the First World War broke out, negotiations came to a complete standstill. In 1916 Eltzbacher received the concession to extract potash salt. On April 22nd, 1922, the three unions Baden , Markgräfler and Zähringen were founded on the initiative of the Karlsruhe Ministerialrat Erich Naumann . The Republic of Baden acquired 434 shares, the Burbach-Kaliwerke 566 shares.

Under the direction of mine director Theodor Albrecht, the construction of was on August 7, 1922 shaft Baden (Tray 1) started. In 1924, the sinking of the Markgräfler shaft (shaft 2) 60 m south of shaft 1 began. In July 1925, shaft 1 reached the potash store at a depth of 786 m, in October 1926 shaft 2 at 779 m. From 1923 to 1927 the construction of the day-care facilities followed (chlorine-potassium factory, power station, workshops, social and administrative buildings, warehouse, works railway, works apartments, etc.). Individual company residences on Grißheimer Strasse were already occupied in May 1923, and the administration building was completed two years later.

In 1928 the regular extraction of raw salt and the production of potash fertilizer began. In 1930 the annual output was 250,000 t of crude salt. Preussag took over the shares in Burbach AG as early as 1933 .

Potash mining

After completion of the two shafts Bugginger the 793-m was initially the sole North and South propelled, then the 754-m level. In between, the first quarries were made. Large stocks had to be tapped here quickly in order to maintain a high production rate.

In the first few years, the mines on both sides of the 793 m level slowly migrated north until they reached the basalt zone in 1936 . Since a penetration appeared too dangerous, the potash store was initially only oriented to the east and west . On May 7, 1934, a mine fire broke out , killing 86 miners. A falling lump of salt probably caused a short circuit in a high-voltage line. The flying sparks ignited fascines used as a delay . In the cemetery there is a memorial on a burial ground for all the victims of the mine.

After the end of the Second World War , which had led to limited mining and production, the plant came under French administration. In 1948, the Baden Potash Company continued to promote the plant with French participation before the plant was taken over by the Baden trade union in 1953.

In 1951 the basalt zone was broken through. To the east of this was a basin that sank to the east and was up to 1000 m deep, into which the 793 m level continued sloping to the north. In the southern field, which was built between 1944 and 1967, there were complicated storage conditions that made mining difficult.

In order to tap new potash supplies , shaft 3 near Heitersheim started its regular extraction on November 19, 1964 . Before that, the underground connection to Bugginger shafts 1 and 2 had been established by December 7, 1962. A factory railway brought the raw salt extracted and ground in Heitersheim for further processing to Buggingen. To the northwest of shaft 3, in the Diapir- West field, the potash salt was stored steeply, which resulted in completely different mining methods for the mine . Most of the production in the last few years of operation came from this field.

Demolition and traces

In 1962, the highest workforce was reached with 1186 employees (around 700 in the mine), including 203 guest workers from several nations (Buggingen has almost 2000 inhabitants). By changing the mining method and after the commissioning of shaft 3 in 1964, the potash plant achieved the highest annual output of crude salt in its history in 1966 with 744,350 t . Already at the end of the same year the decline of the German potash mines was announced due to the first sales problems. These were caused in particular by the North American competition. In 1965 the Preussag shares came to AG Wintershall . In 1967, the rock salt production, which was discontinued in 1950, and bromine production, which was discontinued in 1929 and 1940, respectively, were resumed. In 1970, Wintershall and the state of Baden-Württemberg surrendered their shares to Kali und Salz AG, which was now the sole owner of the plant.

Despite previous promises by Wintershall AG that it wanted to keep the mine, in 1972 the supervisory board of Kali und Salz AG approved the closure of the potash salt mine with a gradual reduction in production and workforce. In September 1972, the closure of the potash plant in May 1973 was announced. This was justified with the inefficiency caused by the difficult mining situation (30 million marks loss).

Many of the workers and employees had already looked for new jobs before the official announcement of the closure plans. The concentration of operations on shaft 3 had led to a further reduction in the workforce. By April 30, 1973, around 300 employees had to be made redundant (from 1,186 in 1962). Many of them found new jobs in metalworking plants in the area; some had moved to other mines when production stopped on April 13, 1973.

The decommissioning and demolition work initially began with the extensive clearing of the underground facilities . After that, the main Bugging plant from the Heitersheim part of the plant was largely demolished. The shafts were filled and covered with concrete slabs.

In April 1996, the mine gases methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen leaked from shaft 3. The State Mining Authority had the shaft opened by specialists from the technical department of Ruhrkohle AG and Deutsche Montan Technologie to allow the gas to flow out. A Protego hood was then installed in order to be able to discharge any escaping gas in a controlled manner.

While relatively much has been preserved at Heitersheim, with the exception of the imposing headframe , only a few parts of the Bugginger “factory” have been preserved, including the gatehouse, the administration building, the canteen and the Monte Kalino waste dump at the northern end of the former plant, which can be seen from afar .

The Bugging factory site was sold to private investors. The typical miners' settlements and company houses are striking in the village. At the end of Werkstrasse there is a private collection of parts of the former mine train including signals and carts. A dirt road runs along the former route.

Pending rehabilitation of the spoil dump

In November 2012, the Federation for the Environment and Nature Conservation Germany again called for a rehabilitation plan for the spoil dump, from which potassium and sodium chloride had been leached for years. This washout, according to BUND seven grams of salt per liter of effluent, is not toxic, but would corrode pipe systems and could make the drinking water inedible. In 2012, it was decided to convert most of the Heitersheim site into a commercial area.

In 2013 up to 2.58 tons of salt was washed into the groundwater every day . The limit of 250 milligrams of chloride per liter stipulated in the Drinking Water Ordinance was exceeded by far with 400 to 2800 mg / l. A renovation has been negotiated for years.

In November 2017, Kali + Salz AG announced that the dump should be covered in order to “protect the groundwater from further salt entry.” The district of Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald expects a contract for the rehabilitation by the end of 2019, the start of which is not yet in sight.

Special waste storage

In 1973 570 (of 1,000 planned) tons of cyanide-containing hardness salts were stored in almost 2,900 barrels in the disused mine.

Difficulty dismantling

The depth and the construction of the Buggingen potash storage area resulted in special mining problems that could only be overcome with a high level of technical and financial effort:

In the area of the southern Upper Rhine Plain , the geothermal depth is 25 m. In the deepest parts of the pit, therefore, the temperature was above 52 ° C. The actual working time of the miners was allowed to be a maximum of 6 hours, in contrast to the 8-hour shift that is usual elsewhere.

Since the rock layers contained mine gas , the potash stores on the Upper Rhine were the only ones in Germany to be classified as endangered by firedamp . The firedamp protection required more complex electrical equipment, special explosives and constant controls.

The hanging wall of Kalilagers is not completely solidified because of its low geological age and sets the prevailing at that depth tamper head against only a relatively small resistance. All cavities (excavations, conveyor lines , etc.) therefore had to be provided with particularly massive expansion . Initially, timber construction was used, followed by steel construction after the great mine accident .

Nevertheless, the constant slump in the tracks could not be completely avoided. Deformations or even collapses were therefore the order of the day. Those areas of the pit that no longer had to be kept open for mining, storage or transport work were therefore treated with dead rock and production residues from the potassium chlorine factory in order to limit subsidence of the earth's surface. Particularly that relating to the mine leading Rhine Valley stretch of the Federal Railroad had to be protected in this way.

working conditions

Workforce

During the sinking work , operations ran continuously day and night, including Sundays and public holidays. For a long time after that, it was still customary for factory employees to meet on Sunday mornings for voluntary shifts.

Originally there were no local miners in Buggingen , the drilling company E. Meyer from Duisburg brought its own staff. The core workforce was made up of a small shaft construction crew from Central Germany, plus unskilled workers from the surrounding area.

Many of the miners recruited in the following period soon returned to their homeland due to a lack of apartments. Therefore, workers from the Markgräflerland were increasingly hired. In the area between Freiburg and Schliengen there was hardly a place from which not some residents were active “in potash”.

In 1927, the shift wage of a worker was 8.03 Reichsmarks (6-hour shift), a factory worker in processing received 6.32 RM.

Changing work

The working methods of the Bugging miners and the corresponding machines remained almost unchanged for a long time. In some cases, however, they changed fundamentally, especially towards the end of the 1960s. Let us outline the work of the mason and his teacher as an example . This team carried out the drilling and blasting work .

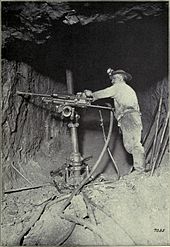

For a long time, the job of a miner in the dismantling process was to first drill a pattern of 5 to 8 m deep blast holes in the potash store with his electrically operated, fire-proof pillar drilling machine. Among other things, the apprentice had to score the drill starting point with his hoe, attach the rod and keep it stable during the first few turns.

The boreholes were then filled with explosive cartridges, provided with detonators and ignition cables (until around 1940 detonating cord ) and sealed. Tin boxes were used for transport, and from 1966 explosive cartons. The tusk finally triggered the detonation by burning the fuse or by operating the blasting machine from a safe distance.

With the relocation of the mining field to the north to the partly steep Heitersheimer Revier towards the end of the operating period, around 1970, the mining process and thus the work of the mining team changed decisively. The storage conditions allowed the use of large devices, which replaced the column drilling machines that had been used for more than 40 years .

The tusker operated a mobile drill carriage with a drill carriage , marking and “hacking” by the teacher was usually no longer necessary. The explosive was no longer pushed into the borehole in the form of a cartridge, but was blown in loose. Special stocking vehicles were available for this purpose.

Equipment: miner's lamps

In Buggingen, carbide lamps were used in the construction of shafts 1 and 2 and in the subsequent drives into the potash store . The lamps were filled with carbide and water and made ready for use by the miners before starting the shift.

Because of the danger of firedamp, only electric miner's lamps were allowed to be used from 1929 . These were robust team lamps (hand lamps) with an alkaline battery and a weight of around 4 kg. These lamps have been converted for special uses and B. equipped with a red light as a tail light for locomotives and a blue light for the transport of explosives. Supervisors and visitors used light, battery-powered "speed cameras" in various designs that could be carried with a leather strap across the chest.

Since the early 1960s, the unwieldy team lamps in Buggingen have been replaced by the much lighter head lamps . The battery was carried on the belt, the headlight attached to the helmet. Petrol safety lamps were used by experienced tusks and weathermen to detect mine gas. A special feature was the compound safety lamp, which could be used both for lighting and for detecting mine gas.

The miner's lamps were kept for days in the lamp room and were maintained by lamp keepers. A lamp burned for one shift . After the introduction of the electric headlamps, lamps were loaded in self-service charging racks. Each miner had his own lamp, which was marked with his lamp number.

Club life

After the closure of the Buggingen potash salt mine, the miners 'association and the miners' chapel have made it their business to maintain and preserve mining customs and traditions for future generations. In the 1930s, the workforce of the potash plant founded the miners 'association "Glückauf" with a marching band and miners' choir. Due to the events of the Second World War, the association dissolved. After the closure, on the initiative of mine director Blomenkamp, the “Bergmannsverein Buggingen e. V. “founded. Hermann Fink was elected the first chairman.

Since 1985 the association with over 500 members has been successfully continued by Ewald Machauer from 1998 by Gerhard Martin. The tasks of the association include participation in anniversaries and funeral ceremonies, the organization of barbara celebrations, miners 'meetings and mineral fairs as well as nationwide participation in miners' days. With the care of the Potash Museum, the miners' association has taken on another particularly important task to preserve the Bugging mining tradition. The miners' band was founded in 1879 as the Buggingen music association. He had to survive severe crises due to the effects of two world wars and periods of inflation.

Under the long-standing chairman Gerhard Winter, the association was renamed "Bergmannskapelle Buggingen e. V. “renamed. In March 1996 Edgar Mond took over the chairmanship. In addition to appearances in the community and in the region, the miners' chapel enriches mining events throughout Germany. It has around 400 members, of which 34 are active and 18 are young musicians.

As a result of the activities of the miners' association and the miners' band, the state association of miners' clubs and music associations of Baden-Württemberg was founded in Buggingen in 1975. The association, chaired by Christian Proß, now has 25 member associations with over 4,000 individual members.

Potash Museum

The Potash Museum at Hauptstrasse 14 in Buggingen was opened on July 6, 1996 and showed the history of potash mining in Buggingen on an area of 29 square meters with display boards and showcases. In 2009 the museum moved to the new building by the visitor gallery ( Am Sportplatz 6a ), which offers around 140 square meters of usable space.

Historical original recordings and exhibits from the operational time of the plant show the path of the mineral fertilizer from the extraction of the crude salt in the mine, through the processing in the "factory", to the dispatch to the customers. Video films provide information about the beginnings, operation and end of the Buggingen potash mine and the German potash industry.

The museum is open on Sundays from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. and admission is free. The visitor tunnel can be visited by appointment.

Visitor gallery

In 2001, the miners' association was able to acquire an old ice cellar at the Buggingen sports field, which was used as an air raid shelter for the population during World War II . In a 3-year construction period, former potash miners dug tunnels in the loess by hand , expanded them, expanded them by mining and equipped them with original mining machines and equipment.

The approx. 110 m long route network of the tunnel is secured with iron and timber construction and equipped with pit lighting, signal systems and pit tracks. Since the opening on May 1, 2005, visitors have been able to get an impression of the workings of the miners and of the mine operation on fully functional machines such as chain conveyors ("tanks"), scrapers and drills. In 2009 the tunnel was expanded.

further activities

In front of the entrance to the former Potash Museum there was a minor bow , which the members of the association installed in 2011 as weather protection at the entrance to the town over the restored Barbara figure (patron saint of miners). At the end of the village in the direction of Grißheim , the association also set up a restored conveyor and tilting lore , which is intended to remind of the mine.

In autumn 2013, members of the association erected a restored pulley as a memorial next to the cart . It comes from the Zeche Groupe Rodolfe from Ungersheim in Alsace , where 23 miners were killed in a gas explosion on July 23, 1940. Miners from Buggingen were present at the funeral as a guard of honor. When the ceremony was repeated in 2007 at a traditional open air event, the Mayor of Ungersheim gave the mining association the rope sheave.

literature

- Otto Geiger: The mine disaster in Buggingen (South Baden) on May 7th, 1934. In: Mining. 65, 4, 2014, pp. 159-164. (Digitized version)

- Lothar Panterodt: The Buggingen potash works - above and below ground . 2013, OCLC 962113002 .

- Thomas Reuter: The shafts of potash mining in Germany (= special houses booklet on the history of the potash industry . Volume 13 ). City administration Sondershausen, Department of Culture, Sondershausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811062-3-7 , p. 26, 93, 128 .

- Friedrich Feßenbecker: The potash salt mine in Buggingen. In: The Markgräflerland. Issue 1/1960, pp. 25-28. (Digitized version of the Freiburg University Library)

Individual evidence

- ↑ In Baden-Württemberg, salts were fundamental raw materials.

- ↑ a b Rainer Ruther: Kali brought prosperity - and death. In: Badische Zeitung. May 7, 2013, accessed November 30, 2013 .

- ↑ Sigrid Umiger: Buggingen: Fear of poison in the potash pit has been around for a long time . In: Badische Zeitung. June 25, 2011, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ↑ Sigrid Umiger: Buggingen: A redevelopment plan is still missing . In: Badische Zeitung. November 23, 2012, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ^ Heike Lemm: Heitersheim: industrial area in the west of the city . In: Badische Zeitung. December 5, 2012, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ↑ Sebastian Wolfrum: Up to 945 tons of salt were washed into the groundwater from the potash contaminated site in Buggingen every year. In: badische-zeitung.de . April 11, 2019, accessed April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Wulf Rüskamp: Contaminated sites from mining pollute the groundwater, but nobody feels responsible. Companies in the Upper Rhine Valley have mined salt for decades. The cost of salinization runs into the millions. There is still no protection and rehabilitation concept. In: Badische Zeitung of September 28, 2019; accessed on October 4, 2019

- ↑ Preference is given to the lesser evil. (PDF) In: Markgräfler Nachrichten. November 7, 1973. Retrieved January 23, 2014 .

- ↑ The regional association. In: lvbergmannsvereine-bw.de. Retrieved January 5, 2018 .

- ^ Buggingen community: Chronicle of potash mining. Retrieved September 24, 2013 .

- ↑ Sigrid Umiger: Buggingen: Museum and memorial: Large mining accident 75 years ago . In: Badische Zeitung. May 3, 2009, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ^ Chronicle - Bergmannsverein Buggingen eV since 1974 "Glück Auf". Retrieved September 24, 2013 .

- ↑ Sigrid Umiger: Buggingen: A bow for Barbara . In: Badische Zeitung. June 10, 2011, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ↑ Sigrid Umiger: Buggingen: Monument for the mining industry . In: Badische Zeitung. October 9, 2013, accessed November 30, 2013.

- ↑ The history of the potash plant. In: Badische Zeitung . January 21, 2014, accessed January 23, 2014.

Web links

- Bergmannsverein Buggingen eV

- The Upper Rhine Graben - Buggingen

- Groundwater salinization in the Upper Rhine Graben

- Mineral Atlas - Buggingen

- private website with additions to the chronology; accessed on November 11, 2016

- State Office for Geology, Raw Materials and Mining in the Freiburg Regional Council (Ed.): Potash salt . January 2016 ( lgrb-bw.de [PDF; 121 kB ; accessed on November 12, 2016]).