Khanate of Crimea

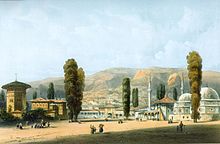

The Khanate of the Crimea ( Crimean Tatar Qırım Hanlığı ) emerged during the power-political disintegration of the Turkic-Mongolian Golden Horde in the 15th century with its center on the Crimean peninsula . Around 1441 the Crimean Tatars, under the leadership of the Giray , a noble family of the Genghisids , founded their own khanate , which comprised the Crimean peninsula, the southern steppe areas of today's Ukraine , and from 1556 the areas of the Nogai horde between Azov and Kuban . The catchment area of the lower Don , which today belongs to Russia for the most part, was added at times . Bakhchysarai , founded in 1454, became the capital of the empire . The Khanate of the Crimean Tatars was the only one of the successor empires of the Golden Horde that existed for a longer period of time, namely until 1783/92. Up until the 18th century, the Crimean Tatars repeatedly undertook campaigns in Ukraine, Moldova and Russia, which at that time belonged to Poland-Lithuania , in which they mainly captured slaves, who were the most important "export goods" of the Crimean Tatar economy. They traded extensively with the Ottoman Empire , whose protection they enjoyed, and became the main promoters and representatives of Islam in Ukraine .

prehistory

From 1280, under the Mongolian Prince Nogai , a great-grandson of Jötschi and great-nephew Batus , the Crimea and southern Ukraine became independent from the Mongol Empire for the first time , but without a khanate of their own. The autonomy ended in 1298 again with the defeat of Nogai against the reigning Khan of the Golden Horde, Tohtu ; Nogai was killed while fleeing in 1299. Favored by internal unrest, Genoa succeeded in establishing trading bases on the south coast of the peninsula from 1266 onwards . The Emir Mamai , who ruled from 1361 to 1380, also used the Crimea as an economic base for his power struggles within the Golden Horde.

The Golden Horde was shaken by internal unrest 120 years later. Acting Khan of the Golden Horde was Dawlat Berdi, also Devlet Berdi, a direct descendant of Berke Khan , a grandson of Genghis Khan . At first he ruled only briefly, from 1419 to 1421. After a defeat by a rival, he retired to the Crimea, where he tried to establish himself. At the same time he led the civil war against Ulug Mehmed , who was now in power. After Vytautas , the Lithuanian ally of Ulug, died, Berdi regained power and ruled the Golden Horde again until 1432.

Foundation of the state and relationship to the Ottoman Empire

The actual founder of the khanate was Hacı Girai , who defeated Berdi's son. His family ties and clan affiliations are unclear, but a blood relationship to Toktamisch , a direct descendant of Genghis Khan , may have existed. Hacı formed an independent khanate in the Crimea in the middle of the 15th century with a few victories and alliances.

The disputes among the ten sons of Haji Girais caused a weakening of the power of Khan Meñli I. Giray (r. 1466, 1469–75 and 1478–1515). An attack by Akhmat Khan (Khan of the Golden Horde 1465–81) forced Meñli to flee to the Ottoman Empire from 1475 to 1478. After he recognized the Ottoman sovereignty while maintaining a high degree of autonomy , the backing of the “ Sublime Porte ” developed from the Crimean Khanate from 1478 onwards into a stable state that was able to assert itself against its neighbors for a long time and pursued a foreign policy largely self-sufficient from the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman sultans always treated the khans more as allies than as subordinates. Several historians describe the Girays as the second most important family of the Ottoman Empire after the House of Osman : "If the Ottomans were ever to become extinct, it was natural that the Girays, descendants of Genghis Khan, would succeed them." Sultan and stood above the Grand Vizier.

The khans continued to mint coins exclusively with their faces and names. They collected taxes independently, passed laws autonomously and had their own tughras . They did not pay tribute to the Ottomans - rather, the Ottomans even paid for the services of Crimean Tatar soldiers. The relationship with the Ottoman Empire is comparable to that of the Polish-Lithuanian Union , both in terms of its importance for the two allies and its duration. The Ottomans used the Crimean Tatars' cavalry in numerous expeditions to Europe and Persia.

Emancipation from the Golden Horde

In June 1502 the Crimean Tatars defeated Shaykh Ahmad , who had ruled since 1481 , the last khan of the Golden Horde, which in the medium term promoted the Russian conquest of other successor states of the Golden Horde, in particular the khanates of Kazan in 1552 and Astrakhan in 1556. Under the khan Mehmed I. Giray , Sahib I. Giray and especially Devlet I. Giray , the Crimean khanate rose to become a major regional power in the 16th century . Polish-Lithuanian and Russian rulers made tribute payments, which were declared as "gifts", to the Crimean khans in order to buy peace for themselves.

Legitimation for the Girays was the appeal to the descent of Genghis Khan. Until 1758 they each provided the khan and represented the khanate in particular towards the Ottomans; However, they ruled together with the Qaraçı and Bey from the most powerful clans of the empire: Şirin (of Persian origin), Barın ( Turkish ), Arğın ( Mongolian ), Qıpçaq ( Kipchak ), and later Mansuroğlu (Turkish) and Sicavut (Persian); Since they were not all of Mongol origin, the Crimean Khanate can only be referred to formally as a Mongolian Khanate.

The Khanate of Crimea entered into alliances with the other important successor states of the Golden Horde, the Khanates of Sibir , Uzbek , Kazakh , Kazan and Astrakhan ; At times the Giray also exerted influence on the domestic politics of the latter two. After the collapse of the Khanate Astra Chan 1556 also were Nogaier (predominantly Mankiten (Mongolian: Mangud) and Mongolian), which were previously allied with the Khanat Astra Chan, an essential factor of power within the Crimean Khanate; In 1758 they even took power in the Crimean khanate and held it until the collapse in 1792.

Campaigns against Poland-Lithuania and Russia

The Crimean Tatars repeatedly undertook campaigns in Central Europe and Russia. Larger expeditions to Central Europe took place e.g. B. 1516, 1537, 1559, 1575, 1576, 1579, 1589, 1593, 1616, 1640, 1666, 1667, 1681 and 1688. These led u. a. to Galicia , Lublin , Podolia and Volhynia .

In the first half of the 16th century, the Russian chronicles counted 43 attacks by the Tatars, and probably also attacks from other successor states of the Golden Horde (here Khanate of Kazan , Astrakhan Khanate ) were counted. As during the Moscow-Kazan wars , the Russian grand dukes had to flee their capital again and again when the Crimean Tatars conquered them. In July 1521 led a campaign against the Muscovite Empire; it ended 15 kilometers from the walls of Moscow, in return, after the conquest of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556), Russian Cossacks also advanced to the Crimea (1559). A Tatar-Ottoman attempt to recapture Astrakhan in the first Russo-Turkish War in 1569 failed, but in the Russian Crimean War from 1570 to 1574 the Crimean Tatars invaded Russia again: After attacks in the Ryazan area, their army broke through the Russian positions on the Oka . From May 24 to May 26, 1571, they burned Moscow almost completely. In July 1571, Crimean Tatar troops crossed the Oka again at Kaschira and marched against Moscow , this time with the support of Ottoman Janissaries . Near Molodi, 40 kilometers south of Moscow, they met a Russian army. The resulting Battle of Molodi on August 2, 1572 ended in a decisive defeat for the Crimean Tatars; this is seen as the beginning of their decline.

Russian incursions

After the fall of the Golden Horde, Russia sought, on the one hand, to finally end the threat posed by the "Tartars" and, on the other hand, to gain access to the Black Sea . In 1559, however, a first attack under Alexei Adaschew on the Crimean Khanate failed. In addition to the Russian attacks, there was an unsuccessful uprising of the Khan against the Ottoman Sultan in 1624; but as early as 1628 he submitted again.

Nevertheless, the khanate remained a power factor in the region throughout the 17th century. In 1648 the Crimean Tatars first concluded an alliance with the Zaporozhian Cossacks of Bogdan Chmielnicki and thus helped the Hetmanate of Ukraine to break away from Poland-Lithuania. During the Second Northern War 1655–1660, however, they allied themselves with the Poles and saved the previous enemy from being divided up by the Russians, Swedes, Transylvanians and Brandenburgers.

Decline and decline

In 1696 the Russians briefly conquered the important port city of Azov on the sea of the same name , but had to cede it to the Ottomans in 1711. Only in the course of the Russo-Austrian Turkish War 1736–1739 did the Russians under Field Marshal Burkhard Christoph von Münnich undertake a punitive expedition to the Crimea, during which most of the Crimean Tatar cities, including the capital Bakhchisarai, were burned to the ground. However, an epidemic in the ranks of the Russian army forced them to withdraw. However, after the victorious war, the Russians were able to keep Azov and the territory of the Zaporozhian Cossacks around Zaporischschja and again had access to the Black Sea.

In 1758 the Nogai rebelled against the Giray and established the Khan until 1787. After the Russo-Turkish War 1770–1774 , the Ottomans had to recognize the “independence” of Crimea in the Peace of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774. In 1783, the Crimea came under indirect Russian rule through annexation : Tsarina Catherine II appointed Khan Şahbaz Giray in 1787 and after him Baht Giray from 1789 to 1792. From then on the khanate was only a “titular empire” or a Russian protectorate . These titular arkhans were initially not recognized by parts of the population or by the Ottoman Empire - there were numerous resistance groups in the Kuban area . Only after the Russo-Austrian Turkish War 1787–1792 did the Ottoman Empire recognize the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Empire with the Treaty of Jassy on January 6, 1792. Many Crimean Tatars then fled to what is now Turkey .

literature

- Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick (ed.): On behalf of the king. An envoy's report from the country of the Crimean Tatars. The "Tatariae descriptio" by Martinus Broniovius 1579 (= monographs of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum. 89). Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz, Mainz 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-2422-0 .

- Alan W. Fisher: The Russian Annexation of the Crimea, 1772-1783. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1970, ISBN 0-521-07681-1 .

- Alan Fisher: The Crimean Tatars (= Hoover Institution Publication. 166). Hoover Institution Press, Stanford CA 1978, ISBN 0-8179-6661-7 .

- Gavin Hambly (Ed.): Central Asia (= Weltbild Weltgeschichte. 16). Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1998.

- Günter Kettermann: Atlas on the history of Islam. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-89678-194-4 .

- Denise Klein (Ed.): The Crimean Khanate between East and West (15th-18th century) (= research on Eastern European history. 78). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-447-06705-8 .

- Kerstin S. Jobst : The Crimean chanat in the early modern times. A historical introduction. In: Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick (ed.): On behalf of the king. An envoy's report from the country of the Crimean Tatars. The "Tatariae descriptio" by Martinus Broniovius 1579 (= monographs of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum. 89). Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, Mainz 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-2422-0 , pp. 17–24.

See also

Web links

- Changing expansion of the khanate (WHKMLA Historical Atlas)

Individual evidence

- ^ Fisher: The Crimean Tatars. 1978, p. 26 f.

- ↑ Sheila Paine: The Golden Horde. From the Himalaya to Karpathos. Penguin Books, London et al. 1998, ISBN 0-14-025396-3 .

- ^ Fisher: The Crimean Tatars. 1978, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ If the Ottoman dynasty is interrupted - a Giray should succeed the throne of Turkey. ( Memento of the original from July 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (engl.).

- ^ Sebag Montefiore . Prince of Princes. The Life of Potemkin. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2000, ISBN 0-297-81902-X .

- ↑ Hakan Kırımlı: Crimean Tatars, Nogays, and Scottish Missionaries: The Story of Kattı Geray and Other Baptized Descendants of the Crimean Khans. In: Cahiers du monde russe. Vol. 45, No. 1, 2004, pp. 61-107.

- ↑ Alexandre Bennigsen , S. Enders Wimbush: Muslims of the Soviet Empire. A guide. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1986, ISBN 0-253-33958-8 .

- ↑ List of Wars of the Crimean Tatars. zum.de (engl.).

- ↑ Michael Zeuske : Handbook History of Slavery. A global history from the beginning to the present. De Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-027880-4 , p. 470 f.

- ↑ Сергей М. Соловьёв : История России с древнейших времен. книга 3 (= Tом. 5-6): 1463–1584. АСТ et al., Москва et al. 2001, ISBN 5-17-002142-9 (Russian).

- ^ Gerhard Thimm: The Riddle Russia. History and present. Scherz & Goverts, Stuttgart et al. 1952, p. 113.

- ^ Nikita Romanov, Robert Payne : Ivan the Terrible. Novel. Habel, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-87179-178-4 .