Bipolar disorder

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F31 | Bipolar Affective Disorder |

| F31.0 | Bipolar Affective Disorder, currently a hypomanic episode |

| F31.1 | Bipolar affective disorder, currently a manic episode with no psychotic symptoms |

| F31.2 | Bipolar affective disorder, currently a manic episode with psychotic symptoms |

| F31.3 | Bipolar affective disorder, current mild or moderate depressive episode |

| F31.4 | Bipolar affective disorder, currently a major depressive episode with no psychotic symptoms |

| F31.5 | Bipolar affective disorder, currently a major depressive episode with psychotic symptoms |

| F31.6 | Bipolar Affective Disorder, current mixed episode |

| F31.7 | Bipolar Affective Disorder, currently in remission |

| F31.8 | Other bipolar affective disorders |

| F31.9 | Bipolar affective disorder, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Bipolar disorder is the established abbreviation for bipolar affective disorder (BAS) . BAS is a mental illness that belongs to the mood disorders ( affect disorders ).

The disease manifests itself through extreme, bipolar opposing (= bipolar e) fluctuations that affect mood , drive and activity level . These deflections occur in phases and extend far beyond the normal level. Those affected swing back and forth between depression and mania without being able to voluntarily control these changes.

Between these episodes, people with bipolar disorder usually return to a normal, normal state. Drive and emotional life are then subject to normal fluctuations again. BAS occurs in different degrees of severity. Individuals with bipolar disorder easily appear as a charismatic personality in the manic episode . However, the potential negative social consequences of the disorder for those affected can be very serious.

Depending on the course, treatment can stabilize it if the disorder is recognized early. In addition to the use of medication, psychotherapy is recommended as a supplement, but not as an alternative. Bipolar disorder does not suddenly appear in a previously completely healthy person, but develops gradually.

The socio-economic impact of this disease on the economy was $ 45 billion in 1991 in the United States alone. According to the World Health Organization, bipolar disorder is one of the ten diseases that lead to permanent impairment worldwide. The increased risk of suicide should not be underestimated either : around 25% to 50% of all people with bipolar disorder make at least one suicide attempt. About 15% to 30% of those affected kill themselves.

Designations

Until a few years ago, bipolar disorder was mostly called manic-depressive illness , manic-depressive psychosis or manic-depressive insanity ( coined by the psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin at the end of the 19th century). Colloquially it is sometimes referred to as manic depression , which is misleading.

The terms manic-depressive illnesses or manic-depressive illness are also used as synonyms and are generally better understood by the public. However, they suggest that it is a temporary and curable change, which in turn is misleading. An expression for bipolar disorder that is often used by doctors and authorities is bipolar psychosis or affective psychosis .

The word psychosis is used differently in the professional world: some only subsume delusion under it, others use the term for all serious mental disorders (to which bipolar disorders certainly belong).

The term bipolar disorder has its origin in Karl Kleist's distinction - since 1911 - between unipolar and bipolar mood disorders (affect disorders). “Bi-” is a Latin prefix meaning “two”, “Pol” means one of two (extreme) ends. One end is seen as the extreme opposite of the other (see the Research History section ).

description

Bipolar affective disorder is characterized by an episodic course with depressive, manic, hypomanic or mixed episodes:

- Depressive phases are characterized by an above-average depressed mood and reduced drive. In severe depression, thoughts of suicide can occur.

- A manic episode is characterized by increased drive and restlessness, which is often accompanied by an inappropriately exuberant or irritable mood. The ability to examine reality is sometimes severely limited and those affected can get themselves into great difficulty.

- Under a hypomania is defined as a not very pronounced mania, typically without serious social consequences. However, hypomania is already well above a normal activity and / or mood spike.

- A mixed episode is characterized by the simultaneous or rapidly alternating occurrence of symptoms of mania and depression. For example, a stronger drive meets a depressed basic mood.

Most often, bipolar disorder begins in adolescence or early adulthood. It is often only recognized many years after the outbreak, both by those affected and by medical professionals. Often there has already been a long period of suffering before treatment begins.

Since the symptoms have a strong impact on decisions and relationships, at the time of diagnosis the life paths can already be significantly influenced by them, especially since they usually begin at a young age when the personality is not yet established. Often there are problems in training, in work and family life, or sudden changes in the curriculum vitae. If the disorder is recognized, the effects can possibly be mitigated with appropriate treatment by specialists.

Bipolar disorder is often associated with creativity . Many successful people are among those affected. The increased drive in hypomanic phases can inspire unusual and daring projects, and goals are often pursued with great commitment.

Bipolar disorder is a fairly common disorder: if lighter cases are also taken into account, according to some studies in industrialized countries, three to four percent of the population will be affected by it at some point in their life.

Diagnosis

Hypomania is often not noticed by doctors or has no history of it, so that bipolar disorder is not treated appropriately. But depression is also often not recognized. The symptoms of manic-depressive illness are even less well known to the general public. As a result, only a small proportion of all affected cases are currently correctly diagnosed.

The following circumstances make a diagnosis difficult:

- 30% mixed state: Just under half of all manias, contrary to popular belief and representation, are characterized by euphoria (cheering as high as the sky) . Often times, it is accompanied by depressive symptoms, which can ultimately (40%) lead to a mixed state. If these mixed symptoms are not recognized as such, misdiagnosis can quickly occur.

- Widespread descriptions cite financial ruin, fearlessness in the case of breakups and delusion in manias as typical elements, so that manias that do not exhibit these phenomena are not perceived as such.

- In mania, there is often excessive alcohol or drug consumption, so that a bipolar disorder is rashly classified as an alcohol or drug addiction.

- When addictive diseases occur as a comorbidity , there is an increased risk that the underlying disease will be masked.

- Depression: Recurrent unipolar depression is the most common misdiagnosis in bipolar disorder. This is due to the fact that hypomanic phases are usually not recognized, reported or inquired about as such.

- ADHD: In children and adolescents, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish it from attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD ).

- Schizophrenia: Psychotic symptoms that can occur in severe manias at their peak often lead to the misdiagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder .

Today, bipolar diseases are diagnosed according to the requirements of the World Health Organization ( ICD-10 ) or the American Psychiatric Society (DSM-5 ). The ICD-10 and DSM-5 are diagnostic catalogs with precise criteria that describe the symptoms and other conditions (e.g. persistence of symptoms over a defined period of time) that must be met for a diagnosis.

According to ICD-10

In the ICD-10 , the International Classification of Diseases, the various forms of bipolar affective disorder are classified under the key F31.-. A distinction is made between ten different forms.

According to DSM-5

The following criteria are taken from the fourth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (a widely used US classification system, abbreviated as DSM-IV). Significant changes in DSM-5 from 2013 are a separate chapter ( bipolar and related disorders ) and the abolition of the mixed phase category . Instead, mixed features (simultaneous occurrence of hypomanic, depressive or manic symptoms) can now be assigned as additional coding in the context of bipolar and depressive disorders .

Manic episode

A. A marked period of abnormal and persistent elation, exuberance, or irritability that lasts for over a week (or hospitalization).

B. During the mood disorder period, three (or more) of the following symptoms persist to a significant degree:

- excessive self-esteem or megalomania

- decreased need for sleep (e.g. feeling of relaxation after only three hours of sleep)

- more talkative than usual or urge to talk

- Flight of ideas or subjective feeling that thoughts are racing

- Absent-mindedness (attention is drawn too easily to unimportant or insignificant external stimuli)

- Increase in targeted activities (either social, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor restlessness

- Excessive occupation with pleasant activities that are highly likely to have negative consequences (e.g. uninhibited shopping spree, sexual tactlessness, or foolish business investments)

C. Symptoms are not better described by the mixed episode criteria.

D. The mood disorder is severe enough to cause significant impairment in job responsibilities or unusual social activities or relationships with others, or requires hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or has other psychotic characteristics.

E. The symptoms are not caused by the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. drug use , medication or other treatments) or a general medical condition (e.g. overactive thyroid ).

Major depressive episode

A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms are present during a two-week period and represent a change in previous behavior, emotional life or performance, with at least one of the symptoms being a depressive mood or loss of interest and joy:

- depressed mood for most of the day, almost every day, indicated either by subjective reporting (e.g., feeling sad or empty) or by observing others (e.g., appearing tearful). Note: Children and adolescents may have an irritable mood;

- markedly decreased interest or enjoyment in all or almost all activities for most of the day, almost every day (determined either by personal report or by observations of others);

- Significant weight loss without diet or weight gain (e.g. a change in body weight of more than five percent in one month) or increase or decrease in appetite almost every day;

- Insomnia or need for sleep almost every day;

- psychomotor restlessness or slowing down almost every day (observed by others, not just subjective feelings of restlessness or exhaustion);

- Exhaustion or loss of energy almost every day;

- Feeling worthless, or profound and inappropriate guilt (which can also be delusional) almost every day (not just reproach or guilt for being sick);

- decreased ability to think or concentrate, or inability to make decisions almost every day (determined by either subjective reporting or observation of others);

- recurring thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurring suicidal thoughts without a specific plan or attempted suicide or planning to commit suicide.

B. Symptoms do not qualify for a mixed episode.

C. Symptoms cause clinically significant suffering or impairment in social, professional, or other important roles.

D. The symptoms are not based on a direct physiological effect of a substance (e.g. drug use, medication) or a general medical condition (e.g. overactive thyroid).

E. Symptoms are not better explained by grief; B. about the loss of a loved one. Or: The symptoms last longer than two months or are characterized by a pronounced functional impairment, pathological preoccupation with worthlessness, suicidal thoughts, psychotic symptoms or psychomotor slowdown.

Hypomanic episode

A. A marked period of constantly elated, exuberant, or irritable mood, lasting at least four days, that is clearly different from the usual non-depressed mood.

B. During the mood disorder phase, three (or more) of the following symptoms (four if mood is just irritable) are persistent to some degree:

- excessive self-esteem or megalomania

- decreased need for sleep (e.g. feeling of relaxation after only three or fewer hours of sleep)

- more talkative than usual or urge to talk

- Flight of ideas or subjective experience of racing thoughts

- Absent-mindedness (this means focusing on insignificant or insignificant external stimuli)

- Increase in targeted activities (either social, professional, or school, or sexual or psychomotor restlessness)

- excessive engagement in amusements that have highly painful consequences (e.g. unrestrained shopping spree, sexual indiscretions, or reckless business investments)

C. The episode is accompanied by changes in performance or behavior that are uncharacteristic of the person in symptom-free phases.

D. The mood disorder and the change in appearance are observed by others.

E. The episode is not severe enough to cause significant social or professional impairment, or to require hospitalization, and has no psychotic characteristics.

Q. The symptoms are not caused by the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. drug use, medication, or other treatments) or a general medical condition (e.g. overactive thyroid).

Note: Episodes similar to hypomania that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (medication, electroshock therapy, light therapy) should not be assigned to a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder .

Comorbidities (comorbidities)

In adults, alcohol and other drug abuse with 3.2 the most common concomitant disease , followed by panic disorders and personality disorders . Drug abuse occurs mainly in postmanic mixed states and the subsequent severe depression.

Phases of illness

Mania (manic episode)

During a mania, the person concerned often focuses his full capacity on mostly pleasant aspects of his life, with other aspects being neglected or completely ignored. It can happen that the person concerned focuses all his energy on his professional or voluntary commitment, for a new partner or on sexuality, but at the same time important or more important things such as B. completely neglected his household or his job or his family. The increased willingness to perform can initially also lead to success. In this way, the person affected can achieve very respectable achievements during mania, but even more so with hypomania, if the talent is present. The excessive sociability and quick-wittedness can also be well received. However, sleep is extremely reduced and the body is correspondingly overworked.

With stronger manifestations it can lead to a loss of reality and delusion . This is often the case in postmanic mixed states. The overestimation of oneself and the feelings of grandiosity during mania can turn into megalomania ( megalomania or Caesar madness ). A religious delusion, even religious megalomania, can occur. Hallucinations can also be caused because of the sometimes extreme lack of sleep caused by the mania .

Many of those affected find it difficult to see a normal state or normality as desirable. It is therefore not uncommon for the hypomanic state to be preferred, which often leads to compliance problems with phase prophylaxis .

Hypomania

Hypomania is the weakened form of mania. Special features are the elevated basic mood and increased drive, which can be associated with simultaneous changes in thinking in the sense of a more erratic, less concentrated thinking ( flight of ideas ) and a change in psychomotor skills. The livelier mood leads to greater self-confidence, an increased willingness to take risks and breaches of boundaries. The efficiency is highest in this state.

Depression (depressive episode)

Depression reverses all aspects of mania and forces the sufferer to become apathy and listless. In this phase of the disease of extreme suffering, death very often appears to be a better condition. Acts from the manic phase often put people to shame. Depression is felt to be much worse than a depressed mood , which many healthy people occasionally experience. Depressive episodes are more common as people get older.

Gradient forms

Manic or depressive episodes often, but not exclusively, occur after a stressful life event. The first appearance of the disorder can happen at any age. However, the first symptoms usually appear between the ages of 15 and 30. Those affected usually go through four different phases in the first 10 years. The frequency and duration of the individual phases are very different. In general, however, it can be said that manic phases usually last a little shorter than depressive episodes, that the intervals between the phases become shorter over time, and that with increasing age, depressive phases occur more frequently and last longer. After a few phases of the disorder, internal rhythms can develop that also work independently of external events. Occasionally, if after the first or the first episodes no more occur, i.e. if they are not recognized and treated adequately quickly enough, bipolar disorder appears to many as a lifelong, chronic disorder.

There is a feedback link between the experiences and actions of a person on the one hand and his biochemistry and symptoms on the other. Lack of insight (in the manic phases) is a symptom of the disorder, without this element the self-damaging behavior would not be possible. The more time passes before insight is gained, the more brain structures are shaped, which has a negative impact on the prognosis . In addition, there is the influence of disorder-related decisions (problems at work and in relationships, debts) on life options.

According to the latest studies, up to 40% no longer achieve their original functional level after periods of mania or depression. 40% of those affected have a favorable psychosocial course or can maintain their social environment or their position in society. In the case of permanent symptoms such as poor concentration or fatigue , one speaks of residual symptoms. If the disorder lasts longer with several longer hospital stays, there is a risk that the person concerned will often lose social stability, often also the workplace. Sometimes the family breaks up.

Bipolar I - Bipolar II

The bipolar disorders are divided into bipolar I and bipolar II .

As Bipolar I is a 7 to 14 days or even less frequently prolonged manic episode designated (peak phase), followed by at least one major depressive episode. Bipolar I disorder occurs in about one to two percent of the population. Women and men are equally affected.

Bipolar II includes a depressive episode lasting at least 14 days , followed by at least one hypomania (milder form of mania). Bipolar II disorder occurs in around four percent of the population. Bipolar II disorders can be confused with recurrent depressive disorders (depression that recurs after an intermediate state of normality ) if the hypomanic phases are not recognized.

Switching - cyclothymia

Switching (polarity change) is called the seamless change between mania (or hypomania) and depression.

With cyclothymia , those affected are exposed to slight manic and depressive fluctuations for at least two years, which are, however, still well above normal mood fluctuations. According to ICD-10 , cyclothymia is not counted as a bipolar disorder.

Rapid cycling

Rapid cycling is used to describe at least four mood swings per year, ultra rapid cycling describes mood swings within a few days and ultradian rapid cycling (ultra-ultra rapid cycling) the changes within a few hours. Patients with rapid cycling are often treated in a clinic. They need special therapy because the frequent change of episodes can often not be adequately treated with classic medication and therefore mood stabilizers are usually used. The causes have not yet been clarified. The risk of suicide is high with Rapid Cycling and the prognosis is worse.

Mixed states (dysphoric manias)

When depressive and manic symptoms occur in rapid succession during a bipolar episode, or when depressive and manic symptoms mix simultaneously, this is called a mixed manic-depressive state or a mixed episode. The affected patients can e.g. B. Thinking or speaking very quickly, as is typical of a manic episode. At the same time, however, they can be very anxious, have suicidal thoughts, and suffer from depressed mood; Ultra- and Ultradian Rapid Cycling can also be found in these episodes in patients who are otherwise not affected by this type of switching. Mixed states often occur in the postmanic phase and are also due to the fact that those affected in the manic phase are no longer able to sleep properly. They are common and occur at least as often as classic manias. The increased drive can cause depressive thoughts to be put into action, so that the risk of suicide in these states is much higher than in pure depression, in which the drive is paralyzed. As with Rapid Cycling, mood-stabilizing psychotropic drugs are often used here . These are severe episodes that are more difficult to treat than the classic phases of bipolar disorder.

Suicide risk

People suffering from bipolar disorder generally have a much higher risk of suicide . On average, 15 to 30% committed suicide. In some areas - as has been shown for Scotland - the suicide rate of those affected is 23 times higher than the population average, and at some stage of life - for example within two to five years after the first manifestation - suicides occur particularly high.

Depression in which the paralysis of the drive is not yet present or has already improved somewhat so that suicide can be implemented is particularly risky. Mixed phases (mixed states), in which agonizingly manic and depressive symptoms occur at the same time, harbor a risk of suicide due to the dysphoric or desperate mood and the extremely high level of drive. Another reason can persist between the phases even with clear thinking: People who suffer from bipolar disorders with an unfavorable prognosis and many phases they have already lived through know that depression will come again and again and how painful it is.

Psychoactive substances

In addition to stress and lack of sleep, psychoactive substances such as caffeine , alcohol , tobacco smoke and other drugs also have an adverse effect on bipolar affective disorders. In addition, interactions with the prescribed medication can often be expected, which is why it can usually be an advantage not to use them completely.

- Caffeine has a negative effect on the length of sleep and promotes nervousness and restlessness; Affected people can be particularly susceptible to this and could trigger mania as a result.

- In addition to the risk of addiction, alcohol has a negative effect on the depth of sleep and the duration of sleep, contrary to popular belief, and has a disinhibiting effect, which is contrary to anti-manic prophylaxis. On the other hand, alcohol exacerbates depression.

- Cannabis is used by some people as self-medication. Despite the possible positive effects, it should not be forgotten that withdrawal and indolence as depressive characteristics and paranoia as a manic characteristic can be increased many times over by cannabis, which in turn counteracts recovery.

- Cocaine is also suspected of causing manias, and indeed there are behavioral similarities between a manic and a person who uses cocaine as a drug.

- Amphetamine (speed) can trigger both manic symptoms at the height of intoxication and depressive patterns when the euphoria subsides. Amphetamines cause or worsen mood swings, including a. Restlessness, lack of sleep and emerging insecurity can have the most long-term effects on the psyche.

causes

The development of a bipolar disorder is most likely multifactorial ( vulnerability ). Both genetic factors and psychosocial triggers are likely to play a role, that is, the genetic makeup sets a framework for the probability ( predisposition ), and the environmental factors influence the development, course and end of the disorder.

Heredity and Genetics

Based on twin studies , the inheritance of an increased risk of BAS has been estimated to be over 80%. However, whether - and under what conditions - hereditary risk factors actually lead to a disease is an extremely complex and so far largely unanswered question.

A 2015 review showed that a large number of genetic changes had been identified to date, but that - each on their own - only meant a slightly increased risk for the development of BAS. The general theme is that only several common changes ( polygeny ) could lead to an outbreak of the disease. The provisional nature of the current (2015) level of knowledge is made clear, among other things, by the fact that the genetic deviations found so far - despite their large number - can only explain a small percentage of the heredity found in relationship studies. Furthermore, the identified genetic changes are not specific to BAS, but also involve increased risks for other diseases. In addition, their precise functional consequences in the organism are still largely unclear. Therefore, the prerequisites for meaningful genetic tests on patient or risk groups have not yet been met in any way. However, promising results with respect to lie about the signal transduction by calcium ions (Ca 2+ ) in nerve cells before, and it is becoming apparent that the heritable changes to a large extent regulation and expression ( expression ) of genes relate.

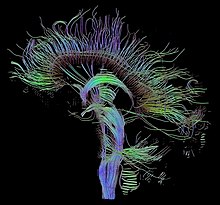

Neuroimaging

A 2014 overview study summarized the results of brain imaging tests as follows. At BAS there are “clear deviations” in the neural networks that are involved in the processing of feelings, the regulation of emotions and the reward system. The functional deviations were assigned to the following anatomical changes: decreased volume of gray matter in the prefrontal and temporal cortex, in the hippocampus (memory functions) and in the amygdala (sensory reactions) as well as decrease in volume and function of the white matter , the prefrontal and subcortical (such as amygdala and Hippocampus) connecting regions. Another overview study from 2014 found that the white matter deviations were also observed in adolescents with BAS or those at risk for BAS. This might this change is apparent the prospect of the future in the early detection and prevention ( prevention ) of BAS to use.

Neurochemistry

Disturbances in neurochemical signal transmission mainly affect four of the most important neurotransmitters : the three monoamines noradrenaline , dopamine and serotonin, and especially glutamate . Additional deviations within the nerve cells in the secondary messenger substances ( second messengers ) play a decisive role and are necessary components of the theories on the origin and course of BAS. While the knowledge about disorders in the neurotransmitter systems is already being used therapeutically, there are currently (as of 2015) no concrete prospects of having a therapeutic influence on the much more important deviations within the nerve cells.

Psychosocial factors

Environmental influences and personality traits also play a decisive role. Critical life events such as trauma or psychosocial stress can trigger phases of illness. Individual mechanisms are known, but no integrating etiopathogenetic model can yet be derived.

The weakness of self-esteem , an irregular day / night rhythm or alcohol and other drug abuse are also discussed as triggering factors . Up to 75% of those affected report in retrospect that they had intense stress immediately before the first noticeable episode of the illness - stress, however, that would not have triggered a manic or depressive episode in people without disposition . Later disruption phases can be explained less and less with stressful events, or they can already trigger minimal stress.

treatment

Due to a lack of insight on the part of those affected, especially in manic episodes or in the event of an acute risk of suicide , treatment in acute phases of mania or severe depression sometimes has to be carried out as compulsory treatment against the will of the patient . In most cases, however, those affected show understanding and allow themselves to be treated voluntarily because of their high level of suffering. However, when manic phases occur for the first time, those affected cannot understand because they have not yet gained any experience of the serious negative consequences. For many, the insight only comes after several phases. It is very helpful for successful treatment if those affected find out about their disorder and read a lot about it so that they can understand for themselves which treatment is best in which phase. This also applies so that they can learn how to counteract them in good time, which is necessary to reduce the stress. A correct diagnosis is a prerequisite for successful treatment.

Depending on the course and severity, stabilization can also be achieved in mild cases with psychotherapy alone. Early detection of the fault is an important factor here. For adolescents, this can usually only be done by an experienced child and adolescent psychotherapist or psychiatrist, as the symptoms are very similar to other disorders and there is therefore a risk of misdiagnosis. In addition, drug treatment can take place, the prescription of which belongs in the hands of a psychiatric specialist. Bipolar disorder does not occur suddenly in a previously completely healthy person, but develops gradually. Due to a lack of knowledge in public and sometimes also among doctors, as well as the reluctance to deal with mental disorders, comparatively mild symptoms are often not intervened for years - possibly also out of fear of medication. The course can be positively influenced by making a diagnosis early and with regular discussions.

Medication

Different medications are used in different episodes. A distinction is also made between acute therapy, maintenance therapy and prophylaxis. Mood stabilization through phase prophylactics is the basic structure of any drug therapy.

mania

In acute and severe mania, neuroleptics are usually administered. Typical neuroleptics (e.g. haloperidol or loxapine ) usually work quite reliably, but have the disadvantage of movement disorders ( extrapyramidal disorders) as a side effect. Atypical neuroleptics such as risperidone , quetiapine , olanzapine , aripiprazole , ziprasidone have a lower risk of extrapyramidal disorders and have also proven themselves in adolescents in acutely manic and mixed phases. The risk of side effects here relates more to metabolic diseases through to diabetes .

Neuroleptics can also be used when a manic episode is looming, which often prevents a full onset.

Mixed states

Mixed conditions are complicated to deal with. Usually several drugs have to be combined. On the one hand, they can be treated with newer atypical neuroleptics, on the other hand, the depressive symptoms must also be treated. It may be the case that long-term use is necessary if psychotic symptoms recur on withdrawal.

depression

Antidepressants are compared to mood stabilizers ( Mood stabilizers ; see prevention) no additional benefit, but rather risks such destabilization increase of mania, phase frequency ( cycling ) and burdensome Miss Gelaunt unit ( dysphoria ).

For the treatment of depressive emergencies ( suicide risk ) with BAS, the rapid action of ketamine , an antagonist of the glutamate - NMDA receptor complex , has proven itself in clinical research since 2010 .

According to preliminary results from 2013, a very low dose of ketamine under the tongue ( sublingual ) in BAS depression can have both a rapid and - with regular use - a lasting positive effect on mood, stability, perception and sleep.

In mid-2015, the pharmacology professors Lutz Hein (University of Freiburg) and Roland Seifert (Hannover Medical School) reported that ketamine was already off-label , i.e. without official approval by the drug authorities (but completely legally), to depressive and suicidal patients for good reasons is prescribed.

Prevention of episodes

A preventive treatment ( prevention ) to reduce the likelihood of disturbance episodes in BAS is done with mood stabilizers ( Mood stabilizers ; phase prophylaxis ), such as lithium or antiepileptics such as valproic acid , lamotrigine or carbamazepine .

About a third of BAS patients treated with lithium respond extremely well ( excellent lithium responders ). In them, it completely prevents further episodes - without other additional measures ( monotherapy ) - for ten years or longer. In BAS, lithium also has protective effects in the brain ( neuroprotection ), including by triggering an increased production of the growth factor BDNF . Both this protective effect and the preventive effect are related to a large number of already identified genetic properties that are being mapped and researched by the Consortium on Lithium Genetics (ConLiGen), including specifically on the effects of BAS.

Among the anti-epileptic drugs, lamotrigine is considered to be very effective against bipolar depression, but has no proven effects against mania. Carbamazepine and valproic acid, on the other hand, work almost exclusively against manias.

Discontinuing successful treatment with phase prophylactic agents should be carefully considered, as the recurrence of depressive and manic phases can have a negative overall effect on the course of the disease and make renewed treatment considerably more difficult.

psychotherapy

General

A cognitive behavioral therapy and / or conversation psychotherapy and / or sociotherapy and / or psychoeducation tailored to the disorder make sense . We also recommend self-help groups , such as those that have come together in the bipolar self-help network .

It makes sense for those affected is to develop their own warning systems in order not to fall back into extreme phases, with stress management , self-monitoring , self-regulation and self-management . The recognition of the personal early warning signs of the depressive, manic or mixed phases and timely countermeasures through appropriate behavior (e.g. antidepressant activities when there is a risk of depression; antimanic behavior such as enough sleep, restriction, stimulus shielding when there is a risk of mania and the right medication for right time) can prevent a new episode from breaking out. A regulated, stress-free, fulfilling life with sufficient sleep, exercise (sport) and meditation or yoga can delay new episodes or, less often, prevent them completely. The prerequisite for this is that those affected have recovered from the consequences of the last episode.

effectiveness

In a comparative review from 2011 of more recent randomized controlled studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapy in BAS, the following results were reported: The majority of the studies showed significant positive results in the form of a reduction in relapse rates, increased quality of life, better coping with everyday life or more favorable development of symptoms. This confirms the trends of two comparable overviews from 2007 and 2008.

Spread and course

The probability of developing a bipolar affective disorder during life ( lifetime risk ) is 1.0 to 1.6% in a wide variety of countries. There is no difference in risk between men and women.

The risk of developing a high phase frequency (rapid change between elevated and depressed mood) increases with the duration of the disease. About 10% of those affected develop forms of disorder with four or more episodes per year. This goes hand in hand with a more serious prognosis. According to initial studies, 80% of the so-called Rapid Cycler appear to be women. About a third of the patients do not achieve full remission as part of their disorder (symptom-free interval).

75% of patients experience their first episode by the age of 25. 10% to 15% of those affected have more than ten episodes in their life. 39% of patients have another psychiatric diagnosis.

BAS in children and adolescents

Up to now the frequency of the occurrence of a manic-depressive episode in childhood and adolescence is estimated to be relatively low with a value of less than 0.1%. However, there are some indications that this value underestimates the actual frequency of occurrence, since some psychiatrists assume that in child psychiatric and psychological practice misinterpretations of the symptoms of hypomania and mania in the direction of ADHD and behavioral disorders occur. Common comorbidities are anxiety disorders and aggressive behavior disorders .

Young male patients in particular show mood-incongruent psychotic features in 30% of cases. When it comes to ADHD, many symptoms overlap. Indications of the bipolar disorder arise mainly from: an episodic course, a significantly higher impairment and - in the case of mania - from ideas of size and overestimation of oneself as well as reckless behavior. A precise anamnesis is therefore essential.

Incorrect treatment with stimulants such as methylphenidate or modafinil can exacerbate the symptoms of hypomania and mania, which can lead to temporarily unfavorable conditions and even physical damage. Compared to purely unipolar depressives, adolescents with bipolar disorder have a higher risk of suicide.

Research history

Antiquity

Bipolar disorder has been known for a long time. The first written documents from antiquity already prove the knowledge of the two conditions, initially as separate diseases by the famous doctor Hippocrates of Kos . Already some centuries later realized Aretaeus of Cappadocia , the togetherness of depression and mania .

Hippocrates of Kos described in the 5th century BC The melancholy (could correspond to today's depression). He assumed that it was caused by an excess of black bile , which was excreted into the blood by the organically diseased spleen , flooding the entire body, penetrating the brain and causing depression. The Greek word Melancholia is closely linked to this idea (Greek: μελαγχολια from μελας: melas : "black", χολη: cholé : " bile "). Hippocrates also used the term mania (mania) to describe a state of ecstasy and frenzy. This term (Greek μανία: manía : frenzy) has remained in science since then. Instead of the Greek word melancholy , the technical term depression is used today for the other extreme pole of this disease, which comes from the Latin language (Latin depressio "to depress").

The Greek doctor Aretaeus of Cappadocia suspected similar physical causes, but recognized as early as the 1st century AD that the two extreme states, which are so far apart as opposing poles, were related, and thus was the first to describe the bipolar disorder: In my opinion, melancholy is without Doubt the beginning or even part of the disease called mania ... The development of a mania represents an increase in the disease rather than a change to another disease.

Modern

The concept of the Aretaeus of Cappadocia, which had been forgotten in the Middle Ages and the early modern period , was taken up again in the 19th century: In 1851 Jean-Pierre Falret described "la folie circulaire" (= circular insanity) as a change of depression , Manias and a healthy interval, Jules Baillarger three years later his concept of “folie à double forme” as different manifestations of the same disease, although there is not necessarily a free interval between these two extreme states.

In 1899, the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin called this disease of "circular insanity" also "manic-depressive insanity", whereby he also recognized mixed states in which manic and depressive symptoms occur simultaneously. For Kraepelin too, mania and depression were expressions of the same illness.

During the National Socialist “ annihilation of life unworthy of life ”, which was supported - in some cases also initiated - by several psychiatrists, manic-depressives (“circularly insane”) were classified as “ hereditary diseases ”, forcibly sterilized or - then with the diagnosis of “schizophrenia” - murdered in the gassing institutes of Operation T4 .

Since 1911, Karl Kleist differentiated between unipolar and bipolar mood disorders (affect disorders), and in 1957 Karl Leonhard used this concept to differentiate between unipolar and bipolar disorder in depression.

Living with Bipolar Affective Disorder

As with other diseases, there are lighter or more severe courses. The earlier the disease is detected, the better. By recognizing the early warning signs and taking countermeasures and medication, one can lead a full life. For a large number of patients, professional and social mobility are not significantly impaired.

Effects of unfavorable courses

Mental chaos can quickly develop during a mania. By being over-excited during this phase, those affected cause damage and are no longer able to do anything sensible. Depression and mixed episodes, which are particularly agonizing in people with bipolar disease, really throw those affected off course and paralyze them. Legal transactions that were carried out by the person concerned in the context of a manic phase to the detriment of the person concerned can be reversed if the person concerned is found to be incapable of doing business (e.g. the conclusion of several rental agreements or the purchase of several vehicles that are not needed).

People with bipolar disorder are exposed to severe impairments and suffering in their everyday lives. But relatives of those affected also suffer greatly from one, but mostly from several of the consequences listed:

- To cheat on

- financial ruin

- Aloof, restless, or conspicuous behavior in the context of a mania

- Occupational disability

- Elimination of cooperative supportive behavior in phases of depression as well as the grueling return of such phases

- Comorbidities such as alcohol abuse

- Stigma and exclusion

If those affected represent an acute threat or danger to themselves and / or others, they can also be admitted to a psychiatric clinic against their will, either in the context of public-law placement in the event of imminent danger or in connection with care-law placement in advance applied for at the guardianship court and must be approved by an independent psychiatric expert commissioned by the court. The responsible judge of the guardianship court has the duty to hear the person concerned personally against the will of the person concerned prior to placement. If the placement took place by way of a temporary injunction , the hearing must be made up for at short notice. Since mania means a high phase of emotions for those affected personally, they often refuse to voluntarily take medication that would combat this high phase. If the strict requirements that the legislator places on a forced placement, which means a massive restriction of freedoms, are not met, relatives often have to "sit out" the phase, which can last for several weeks and be accompanied by serious psychosocial problems. In this case, social psychiatric services , groups of relatives or the general social service of the responsible youth welfare office offer help .

Children and adolescents, for example, suffer from mothers or fathers being completely or partially absent from their upbringing and household tasks in their acute phases. It can be difficult for children to come to terms with the fact that one parent does not correspond to the role model that is usually associated with the role of mother or father during this time . Fears of inheriting the disorder are common and require professional assistance in dealing with the parent's idiosyncrasy and importance in one's own life.

It has proven to be very important that relatives, who often have to be so supportive, do not forget to think about themselves again and again . Psychotherapeutic rooms in which relatives are encouraged to admit negative emotions to the affected family member towards themselves and to express them in the therapeutic situation have proven to be positive and relieving.

Destigmatization and creativity

Those affected not only struggle with the problems that they often lose the support of friends and family members, but that they are marginalized from society. Numerous celebrities who are affected themselves, stand by it and speak about it publicly, fight against the discrimination.

In the meantime there have been attempts to integrate the creativity boosts often associated with bipolarity through modern treatment methods as a positive aspect of this disorder. Various measures such as medication and different types of therapies - e.g. As cognitive behavioral therapy, art therapy , creative studio, sometimes even simple care to compensate for possibly suffered shock experiences in childhood and adolescence - should help to get the creativity.

An official project that tried to strengthen the creative self-confidence of those affected and to achieve greater recognition in society was e.g. B. 2005 the German internet platform BipolArt by Magdalena Maya Ben, which worked under the patronage of the bipolar doctor Kay Redfield Jamison .

However, one should refrain from exaggerated expectations regarding manic creativity. For example, Kay Redfield Jamison's 1994 estimates that the incidence of bipolar disorder in “creative personalities” is 10 times that in the general population should be taken with caution. Her claim that "more than a third of all English and Irish poets born between 1705 and 1805" suffered from bipolar disorder and "more than half from mood disorders" is unprovable and very likely greatly exaggerated.

prevention

The issue of power of attorney is of crucial importance for bipolar people . In a “normal” phase, you should already be clear about what you want in the event of endangering yourself or others. The so-called Bochum declaration of intent can be used as a model for this declaration of intent .

See also

literature

Guidelines

- S3 guideline for diagnosis and therapy of bipolar disorders of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN). In: AWMF online (as of March 2019)

- S3 guideline on psychosocial therapies for severe mental illnesses of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN). In: AWMF online (as of October 2018)

psychiatry

- Hans-Jörg Assion, Wolfgang Vollmoeller: Handbook of bipolar disorders. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-018450-4 .

- Jörg Walden, Heinz Grunze: Bipolar Affective Disorders. Causes and Treatment. Thieme, Stuttgart / New York 2003, ISBN 3-13-104993-6 .

- Michael Bauer (Ed.): White Paper Bipolar Disorders in Germany, State of Knowledge - Deficits - What needs to be done? 2nd Edition. Norderstedt 2006, ISBN 3-8334-4781-8 .

- Frederick K. Goodwin and Kay Refield Jamison: Manic depressive illness. Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-19-503934-3 .

- Kay Redfield Jamison : Touched with fire. Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament . New York 1993, ISBN 0-684-83183-X (English).

- Volker Faust: Mania. A general introduction to the diagnosis, therapy and prophylaxis of pathological high spirits. Enke, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-432-27861-6 .

- Klaus Dörner, Ursula Plog, Christine Teller, Frank Wendt: To err is human. Textbook of psychiatry and psychotherapy. 3. Edition. Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn 2007, ISBN 978-3-88414-440-4 .

- Christian Scharfetter: General Psychopathology. An introduction. Thieme, Stuttgart / New York 2002, ISBN 3-13-531505-3 .

- M. Hatzinger (eds.), JM Aubry, F. Ferrero, Schaad: Pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorders. Hans Huber Verlag, Bern 2006, ISBN 3-456-84326-7 .

psychotherapy

- Thomas D. Meyer, Martin Hautzinger : Manic-depressive disorders . Beltz Psychologie Verlags Union, 2004, ISBN 3-621-27551-7 . Cognitive behavioral therapy tailored to bipolar affective disorder.

- Stavros Mentzos: Depression and Mania. Psychodynamics and Therapy of Affective Disorders . Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-45775-8 . An alternative approach, with which the author tries to explain affective mental disorders psychodynamically, in particular postulates a high value of the type of self-esteem.

- Thomas Bock, Andreas Koesler: Bipolar Disorders. Understand and treat mania and depression . Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-88414-392-1 .

Essays

- Heinz Grunze, Emanuel Severus: Recognizing bipolar disorders. The art of correct diagnosis. In: The Neurologist & Psychiatrist. Special issue 1/2005.

- David J. Miklowitz, Michael W. Otto et al .: Psychosocial Treatments for Bipolar Depression. A 1-Year Randomized Trial From the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. In: Archives of General Psychiatry . Vol. 64, No. 4, April 2007, pp. 419-426 (English); (Full text) .

Web links

- Volker Faust: Mania: Morbid high spirits with consequences. (PDF; 486 kB).

- Information about bipolar disorder on the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) website

- Jochen Paulus: Happiness and Pain of Madness - Bipolar Disorder and its Treatment . SWR2 knowledge; Broadcast with MP3 and download of the manuscript.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b S3 guideline: Diagnosis and therapy of bipolar disorders. Long version 2.0 update from February 2019 (PDF) AWMF, p. 24,85-86 , accessed on June 23, 2019 (see chapter 5.1.2.2.1: Special features of psychotherapy for bipolar disorders).

- ^ Robert MA Hirschfeld, Lana A. Vornik: Bipolar disorder - costs and comorbidity . In: The American Journal of Managed Care . tape 11 , 3 Suppl, June 2005, pp. S85-90 , PMID 16097719 ( ajmc.com ).

- ↑ Österreichische Ärztezeitung 5/2013, p. 31 - PDF, 5.9 MB

- ↑ Heinz Grunze, Emanuel Severus: Recognizing bipolar disorders. The art of correct diagnosis . In: The Neurologist & Psychiatrist. Special issue 1/2005.

- ↑ Classification of bipolar disorder in the ICD-10 (Version 2019)

- ^ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) ( Memento from May 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ E. Severus, M. Bauer: Bipolar disorders in the DSM-5 . In: The neurologist . tape 85 , no. 5 , 2014, p. 543-547 , doi : 10.1007 / s00115-013-3987-1 ( springer.com [accessed March 2, 2019]).

- ↑ Jörg Walden, Heinz Grunze: Bipolar affective disorders. Causes and Treatment. Stuttgart / New York 2003, ISBN 3-13-104993-6 , p. 11.

- ↑ lichtblick-newsletter.de

- ↑ de.brainexplorer.org ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ N. Craddock, P. Sklar: Genetics of bipolar disorder. In: Lancet. Volume 381, number 9878, May 2013, pp. 1654-1662, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (13) 60855-7 . PMID 23663951 (Review).

- ↑ BM Neale, P. Sklar: Genetic analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder reveals polygenicity but also suggests new directions for molecular interrogation. In: Current opinion in neurobiology. Volume 30, February 2015, pp. 131-138, doi: 10.1016 / j.conb.2014.12.001 . PMID 25544106 (Review).

- ↑ B. Kerner: Genetics of bipolar disorder. In: The application of clinical genetics. Volume 7, 2014, pp. 33-42, doi: 10.2147 / TACG.S39297 . PMID 24683306 , PMC 3966627 (free full text) (review).

- ^ PJ Harrison: Molecular neurobiological clues to the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder. In: Current opinion in neurobiology. [electronic publication before printing] July 2015, doi: 10.1016 / j.conb.2015.07.002 . PMID 26210959 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ ML Phillips, HA Swartz: A critical appraisal of neuroimaging studies of bipolar disorder: toward a new conceptualization of underlying neural circuitry and a road map for future research. In: The American journal of psychiatry. Volume 171, number 8, August 2014, pp. 829-843, doi: 10.1176 / appi.ajp.2014.13081008 . PMID 24626773 , PMC 4119497 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ SM de Zwarte, JA Johnston, ET Cox Lippard, HP Blumberg: Frontotemporal White Matter in Adolescents with, and at-Risk for, Bipolar Disorder. In: Journal of clinical medicine. Volume 3, number 1, 2014, pp. 233-254, doi: 10.3390 / jcm3010233 . PMID 26237259 , PMC 4449671 (free full text) (review).

- ^ R. Machado-Vieira, MG Soeiro-De-Souza, EM Richards, AL Teixeira, CA Zarate: Multiple levels of impaired neural plasticity and cellular resilience in bipolar disorder: developing treatments using an integrated translational approach. In: The world journal of biological psychiatry: the official journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. Volume 15, Number 2, February 2014, pp. 84-95, doi: 10.3109 / 15622975.2013.830775 . PMID 23998912 , PMC 4180367 (free full text) (review).

- ^ S. Haack, A. Pfennig, M. Bauer: Bipolar depression - Epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, and course. In: Neurologist . tape 81 , no. 5 , 2010, p. 525 - 530 , doi : 10.1007 / s00115-009-2849-3 .

- ^ S. Derry, RA Moore: Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar disorder: systematic review of randomized trials. In: BMC psychiatry. Volume 7, 2007, p. 40, doi: 10.1186 / 1471-244X-7-40 . PMID 17705840 , PMC 2020469 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ MK Singh, TA Ketter, KD Chang: Atypical antipsychotics for acute manic and mixed episodes in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: efficacy and tolerability. In: Drugs. Volume 70, number 4, March 2010, pp. 433-442, doi: 10.2165 / 11534540-000000000-00000 . PMID 20205485 , PMC 2882025 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ RS El-Mallakh, AZ Elmaadawi, M. Loganathan, K. Lohano, Y. Gao: Bipolar disorder: an update. In: Postgraduate medicine. Volume 122, number 4, July 2010, pp. 24-31, doi: 10.3810 / pgm.2010.07.2172 . PMID 20675968 (Review).

- ↑ AC Nugent, N. Diazgranados, PJ Carlson, L. Ibrahim, DA Luckenbaugh, N. Brutsche, P. Herscovitch, WC Drevets, CA Zarate: Neural correlates of rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in bipolar disorder. In: Bipolar disorders. Volume 16, number 2, March 2014, pp. 119–128, doi: 10.1111 / bdi.12118 . PMID 24103187 , PMC 3949142 (free full text).

- ↑ DR Lara, LW Bisol, LR Munari: Antidepressant, mood stabilizing and procognitive effects of very low dose sublingual ketamine in refractory unipolar and bipolar depression. In: The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. Volume 16, number 9, October 2013, pp. 2111-2117, doi: 10.1017 / S1461145713000485 . PMID 23683309 .

- ↑ Roland Seifert, Lutz Hein : Ketamine for the treatment of depression and suicidality . (PDF). In: BIOspectrum. 4/2015, Volume 21, Springer-Verlag, WISSENSCHAFT AKTUELL, p. 419, accessed on October 19, 2015.

- ↑ JK Rybakowski: Factors associated with lithium efficacy in bipolar disorder. In: Harvard review of psychiatry. Volume 22, number 6, November-December 2014, pp. 353-357, doi: 10.1097 / HRP.0000000000000006 . PMID 25377609 (Review).

- ↑ JK Rybakowski: Response to lithium in bipolar disorder: clinical and genetic findings. In: ACS chemical neuroscience. Volume 5, Number 6, June 2014, pp. 413-421, doi: 10.1021 / cn5000277 . PMID 24625017 , PMC 4063501 (free full text) (review).

- ^ CL Bowden, NU Karren: Anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder. In: The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. Volume 40, number 5, May 2006, pp. 386-393, doi: 10.1111 / j.1440-1614.2006.01815.x . PMID 16683963 (Review).

- ↑ D. Schöttle, CG Huber, T. Bock, TD Meyer: Psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: a review of the most recent studies. In: Current opinion in psychiatry. Volume 24, Number 6, November 2011, pp. 549-555, doi: 10.1097 / YCO.0b013e32834b7c5f . PMID 21918448 (Review).

- ↑ DJ Miklowitz: Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. In: The American journal of psychiatry. Volume 165, number 11, November 2008, pp. 1408-1419, doi: 10.1176 / appi.ajp.2008.08040488 . PMID 18794208 , PMC 2613162 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ M. Hautzinger, TD Meyer: Psychotherapy in bipolar affective disorders: A systematic overview of controlled intervention studies. In: The neurologist. Volume 78, Number 11, November 2007, pp. 1248-1260, doi: 10.1007 / s00115-007-2306-0 . PMID 17604972 (Review) ( extract pp. 1248-1249. ).

- ↑ Eberhard J. Wormer : Bipolar. Life with extreme emotions. Depression and mania. - A manual for those affected and their relatives. Munich 2002, pp. 47-54.

- ↑ Jörg Walden, Heinz Grunze: Bipolar affective disorders. Causes and Treatment. Stuttgart / New York 2003, ISBN 3-13-104993-6 , p. 7 f.

- ^ J. Fear, A. Marneros: Bipolarity from ancient to modern times: conception, birth and rebirth. In: Journal of Affective Disorders. Volume 67, Numbers 1-3, December 2001, pp. 3-19. PMID 11869749 (Review), (PDF)

- ↑ Eberhard J. Wormer : Bipolar. Life with extreme emotions. Depression and mania. - A manual for those affected and their relatives. Munich 2002, pp. 131-138.

- ^ Bochum declaration of intent. (PDF) Retrieved June 23, 2018 .