Maria in the mirror

Maria im Spiegel was a Cistercian convent in Cologne ; it was later popularly called " Monastery of Sion ". It was built in 1246 on the premises that had been taken over from a Franciscan convent and was converted into a Birgitten monastery in 1613 . In the course of secularization , the monastery was closed in 1802.

history

The southern burial ground used by the Romans for the duration of the Roman period along the Severinstraße leading out of town remained undeveloped for centuries, well into the Frankish period. Drawings by the early cartographers Anton Woensam and Arnold Mercator show that in later times they were mainly used for viticulture and agriculture.

In medieval times, this area was predominantly owned by church institutions or in the hands of the patrician upper class of the city. Many female descendants of these families, often related by marriage, founded or joined convents. Due to their social position, their education and, last but not least, the dowries they brought in , these women quickly rose to a leading position within the respective order . As prioresses or abbesses, they skilfully directed their monastic settlements. They used their family ties, which often extended to the top of secular and clerical offices, and increased the prosperity of their communities by receiving endowments and privileges .

Franciscan monastery

Gerhard Quatermar (k) t, a Cologne patrician, gave the Cologne Franciscan Order ( Minorites ) a piece of land in the Severin parish in front of the Katharinengraben for the construction of an oratory in 1229 . Around the year 1245, the friars sold their property to Count Heinrich von Sayn and moved to their new branch in the parish of St. Kolumba in downtown Cologne.

Cistercian convent

At the time when the wine trade of the Rhenish Cistercian monasteries was pushing for new sales markets, the institutions of their city courtyards were also built in Cologne (since the 12th century), and new convents of the order were founded.

The couple left the property of the Minorites acquired by Count Heinrich von Sayn († December 31, 1246) and his wife Mechthild von Sayn , born von Landsberg († November 12, 1285) to a convent of the Cistercians, who named themselves “Maria im Spiegel “(de Speculo S. Mariae) had given. The foundation contained the clause that Mechthild von Landsberg had to continue to dispose of part of the garden and the buildings and the rest should only go to the monastery in the absence of an heir. In the following year, 1247, Pope Innocent placed the monastery under his protection.

Two years after Heinrich's death, in 1248, Pope Innocent commissioned the Cistercian order to build the monastery “S. Mariae in Speculo ”and to place it under the special supervision of the Abbot von Heisterbach .

Monastery and founder names

The name of the convent "Maria im Spiegel" (de Speculo S. Mariae) was possibly the family name of the founder, who came from the Cologne patrician family of the "von Spiegel", whose male representatives owned large courts, and in the sources as officials of the Richerzeche or were listed as aldermen of the city.

Countess Mechthildis von Sayn gave the monastery another consideration in 1283. In this legacy to the nuns she used the passage

- from mine Cloister ze Colne .

The patroness of the monastery, Countess Mechthild, was buried in the Sion monastery under the main altar of the monastery church that she donated. Further donations to the monastery were made in 1280 by Cuno von Horne and in 1331 by Werner Overstolz .

In the vernacular the monastery after the founders Sayn was named in a row. It was called the Monastery of Sion or Seyne, and in Hermann von Weinsberg's time it was called the Jungfernkloster zu Beien. The names of the streets that used to surround the monastery, such as the Seyengasse, the Sionstal, and the streets named after Mechthild (Landsbergstrasse and Mechtildisstrasse) are also reminiscent of this time. Only the then "Bozengasse" changed its name to the present day and became Buschgasse.

Monastery church

The construction of the monastery church coincided with a period of increasing construction activity in the 13th century, when numerous churches and monasteries were built in Cologne. It is not known whether the monastery church grew to its later size during the only few years as a settlement of the Minorites or only under Countess Mechthild. For the building under the Franciscans, the similarity with the church of the monastery Seligenthal near Siegburg , which was also built around this time by the same order, was assumed.

The church building of another Cistercian monastery in Cologne had an even greater resemblance to the one built in Seligenthal. It was the church of St. Maria ad Ortum , completed around 1260 , which was also called "sent Marie garden" and later called Mariagarten. Like this, the Maria im Spiegel church was one of the last sacred buildings in Cologne to be built in the Romanesque style .

For the years 1432 and 1571 there were reports of enormous flood levels in the Rhine, the flooding of which also affected the monastery with its church near the bank. The chronicler "Weinsberg" wrote in a comment on the high water level: the Rhine was on the high water level . He expressed that the water level had flooded the high altar of the monastery church. Documents from these unfortunate years show only little construction activity. The purchase of materials such as wood and ley stones (slate) was only used for repairs and to add to the cloister and farm buildings, but primarily a new roof.

Building description

The church was a five-axis, with cross vaults equipped three-nave pillar basilica . The nave of the church ended on its east side with a round apse . The central nave was 22 feet wide and 107 feet long . The narrow aisles were each 12½ feet wide. The second pillar each had templates of semicircular services and supported the continuous belt arches . The bundled intermediate ribs rested on special half-columns above the gallery base. Triforium-like galleries , the arcades of which were framed by small pillars made of black slate marble , divided the sides. Further decorations were made with gilded leaf capitals and bases. The interior was well illuminated by the side aisles and upper aisles , which were equipped with fan-shaped windows, as well as by the incidence of light from five high, pointed-arched windows in the apse. At the end of the southwest aisle there was an ascending spiral staircase , which led to a corridor at the level of the triforias and a west gallery that may have already existed at the time of the Cistercians . According to a drawing from 1746, the depth of the built-in wooden gallery was two, and according to later information from Sulpiz Boisserée only one yoke .

The exterior of the church was divided by a Romanesque pilaster strip and had a circumferential arched frieze running on pointed consoles . The cornices were pronounced and the windows were embedded in round arches. The roof of the nave carried a typical modest roof turret of the religious churches in the west .

Conversion into a Birgitten monastery

A little monastic behavior of the nuns living in the Maria im Spiegel convent prompted the top church leadership in Cologne to reform the settlement. When at the end of the 16th century the monastery rules were less and less observed by the Cistercian women, there was a change in the way that sisters of the Marienforster San Salvatore order of St. Birgida were relocated to the “Seyen Monastery” in Cologne. Their abbess, Ursula Distelmeyer, took over the management of a branch that subsequently consisted of two convents with the male convent of S. Salvatoris and that of the sisters “S. Mariae ”. In 1614 the archbishop commissioner Johann Weyer ordered another four members of the Marienforster order to come to Cologne. There were three clergymen and one lay brother , to whom, on the instructions of Confessor General Christoph Langen, three more friars from the order in Marienbaum, which was also run as a double monastery according to the rule of St. Birgitta of Sweden , were added.

Monastery complexes

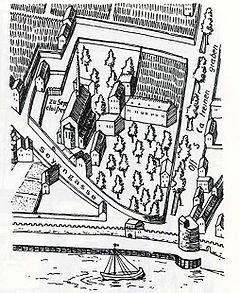

The irregular arrangement of buildings on the monastery grounds shown in Mercator's sketch from 1571 changed after the change of order. As a result, structural adaptations and extensions were made, which corresponded to the order regulations for the coexistence of both sexes in the monastery complex. For this purpose, the female members of the community received a new enclosure, the wings of which surrounded an inner courtyard or cross courtyard about 25 meters square . In addition to the sum of 200 gold guilders , the city council contributed around 25,000 bricks to these expansions . The new buildings erected by the sisters in the middle of the herb garden were connected on the west side via an access to the subsequently built-in nuns' gallery of the church. On the north side was the area of the brothers with a five-sided cross courtyard next to the church. The enclosure there served as an apartment for the prior and the fathers, and an intermediate courtyard led to the tree and vineyards in front of the Katharinengraben. The originally used monastery entrance on Syengasse was preserved.

Well-known abbesses

- Ursula Distelmeyer, came to Cologne with the first Marienforster sisters as abbess

- Catharina de Watzstena, became the first abbess of the Birgittenkloster in Cologne

- Elisabeth Schoels, donated a picture of the Virgin Mary in 1661

- Gudula Clarens is evidenced by an inscription on her tombstone († March 10, 1745)

Repeal

After the secularization of the monastery in 1802, the facility was abandoned for a few years. The domain administration then sold it in 1809 to the businessman Johann Jakob Goedecke, who initially set up the property for residential purposes, but later had a starch factory built on the property . The monastery church stood until 1833; it was demolished because a sugar factory was planned to be built there. Even before the resignation of the church is to Noël , a shamrock bow the west portal of trachyte and slate, into the municipal collection Wallraf have reached (Wallrafianum, Trankgasse 7), and later from there into the Rhenish Museum. A memento mori of the Sion monastery, created around 1800, is now in the city's armory museum .

Foreign possessions

The monastery had large foreign possessions early on.

- The "Berchemshof", in today's Cologne-Longerich

- In “Ahrheim”, today's Ahrem near Lechenich

- In Gleuel , today's district of Hürth

- In Godorf and Wesseling

- The "Neußerhof" in Kenten , a district of Bergheim today

These goods, as far as the monastery still owned them, were also expropriated in 1802.

literature

- Paul Clemen (ed.): The art monuments of the city of Cologne . Supplementary volume: Ludwig Arentz, Heinrich Neu, Hans Vogts : The former churches, monasteries, hospitals and school buildings of the city of Cologne . L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1937, ( Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz 6, 7), (Reprint: ibid 1980, ISBN 3-590-32107-5 ), p. 330ff.

- Hermann Keussen : Topography of the city of Cologne in the Middle Ages . 3 volumes (4 parts). Hanstein, Bonn 1910 ( Prize writings of the Mevissen Foundation 2) (reprint: 2 volumes. Droste, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-7560-9 and ISBN 3-7700-7561-7 ).

- Gerd Steinwascher: The Cistercian town courts in Cologne. Altenberger Dom-Verein e. V., Verlag Heider, Bergisch Gladbach 1981 ( annual edition of the Altenberger Dom-Verein ZDB -ID 219025-4 ), (also: Marburg, Univ., Diss., 1981).

- Winfried Schich : The trade of the Rhenish Cistercian monasteries and the establishment of their city courts in the 12th and 13th centuries . In: Raymund Kottje (Hrsg.): The Lower Rhine Cistercians in the late Middle Ages. Reform efforts, economy and culture . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-7927-1285-7 , pp. 49-73 ( Cistercians in the Rhineland 3).

Web links

- Digitized archive holdings for the Maria im Spiegel monastery in the digital historical archive in Cologne

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Ludwig Arentz, H. Neu and Hans Vogts, in: Paul Clemen (Ed.): Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln , Volume II, p. 278ff

- ↑ Hermann Keussen , Volume II, p. 198, column 1 with reference to: Lacomblet, U.- B. II 160

- ↑ Gerd Steinwascher: The Cistercian Town Courts in Cologne. P. 112

- ↑ Winfried Schich : The trade of the Rhenish Cistercian monasteries and the establishment of their town courts in the 12th and 13th centuries

- ^ Hermann Keussen, Volume II, p. 198, Sp 2

- ^ Book Weinsberg, II, p. 215

- ^ Directory "De Noël" 1820, No. 150/51

Coordinates: 50 ° 55 ′ 40.7 " N , 6 ° 57 ′ 40.7" E