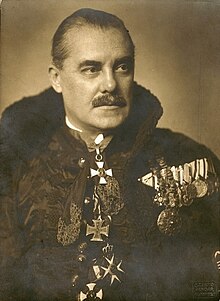

Miklós Kozma

Miklós Kozma von Leveld (born September 5, 1884 in Nagyvárad , Austria-Hungary , † December 8, 1941 in Ungvár , Hungary ) was a Hungarian officer , lawyer , media entrepreneur and politician . In 1919 he was one of the leading counter-revolutionaries around Miklós Horthy . As director of the Hungarian news agency , Hungarian film and radio , he supported the Horthy regime with propaganda . From 1935 to 1937 he was interior minister of the pro- fascist governments of Gyula Gömbös and Kálmán Darányi . After organizing illegal acts of sabotage against Czechoslovakia in 1938 in order to regain the Carpathian Ukraine , in December 1939 he became government commissioner for the area that has since been annexed by Hungary. Here he pursued an aggressive policy of Magyarization and in 1941 initiated the deportation of at least 18,000 people as allegedly stateless Jews to the German territory in eastern Galicia ( district of Galicia ). Most of the deportees were victims of the Kamenets-Podolsk massacre there .

Life

Officer and counter-revolutionary

Kozma was the son of General Ferenc Kozma (1857-1937), who was also a well-known Hungarian poet under the pseudonym Nicolás Bárd . His uncle was the anti-Semitic poet Andor Kozma (1861–1933). Miklós Kozma graduated from the kuk military academy Ludovika Academy and was retired in 1904 as a lieutenant of the 10th Hussar Regiment . In 1911 he passed the Matura . He then studied law and received in 1914, the absolution of Budapest Peter Pázmány University . During the First World War he fought as an officer in the Hungarian Hussars on the Russian and Italian fronts . Most recently he was regiment adjudant with the rank of Rittmeister .

After the revolution in 1918 , Kozma initially worked in the Hungarian Ministry of War . However, because of his counter-revolutionary stance, he was arrested and removed from service in 1919. He went into hiding for a while in Transdanubia and then went to Szeged to join the counter-revolution under Miklós Horthy. Here he took over the management of the propaganda department of the newly established " National Army ". After the fall of the Soviet Republic under Béla Kun and the entry of the National Army in Budapest , Horthy appointed him military policy advisor to the military chancellery and thus head of the military intelligence service . What role Kozma played in the “ White Terror ” in Hungary cannot be said with certainty.

Kozma, Gömbös and Pál Prónay conspired in May 1922 on behalf of Horthy with Gustav Ritter von Kahr , Erich Ludendorff , Max Bauer and Rudolf Kanzler . After the failed Kapp-Lüttwitz putsch , the aim was to found a center for international anti-communist actions in Hungary . German officers and Freikorps members smuggled in , according to the plan of the German counter-revolutionaries, were to be trained in Hungary in order to overthrow the social democratic government and to establish a military dictatorship at a suitable time together with the Austrian Heimwehr in Austria . Hungary was then to invade Slovakia with the army and voluntary corps, while the Home Guard, the Bavarian Resident Army and Bavarian units of the Reichswehr occupied the Sudetenland . Then they wanted to march through Saxony and Prussia to Berlin in order to establish a military dictatorship in the German Empire . The Hungarian officers hoped that this action would revise the Treaty of Trianon and establish Greater Hungary .

Media entrepreneur, propagandist and politician

On August 7, 1920 Kozma accepted the offer to take over the Hungarian Telegraph Correspondence Bureau. This news agency, founded in 1881, became state-owned in 1918. Within a few years, Kozma developed this news agency into the most important Hungarian media company Magyar Telefonhirmondó és Rádió (MTI) by building up an international network of correspondents , the Hungarian Film Office and, in 1925, the Hungarian Radio Corporation, the Hungarian Broadcasting Corporation. In 1930 he also incorporated the Hungarian National Economic Bank into MTI. The MTI had a quasi monopoly in the information sector in Hungary and consistently represented Horthy's Christian-national state idea. In 1934 Kozma was appointed a lifelong member of the Hungarian House of Lords .

Politically, Kozma was primarily characterized by racial anti-Semitism and the will to revise the Hungarian territorial losses through the Treaty of Trianon (1920). On March 4, 1935, he entered the government under Gyula Gömbös, with whom he had been friends since their days together in Szeged, as Minister of the Interior . Kozma had no illusions that Gömbös, who had called himself a National Socialist since 1919 and had founded a "Party of Racial Defense", not only wanted to establish a totalitarian regime, but also wanted to emulate the National Socialist racial policy against Jews. Kozma, on the other hand, had concerns on the one hand about the introduction of a dictatorship based on the German model and on the other hand about the German aspirations for great power, especially since he gave Hungarian revisionism absolute priority. After Gömbös' sudden death in 1936 Kozma remained in office under his successor Kálmán Darányi . He resigned on January 29, 1937 after the leader of the Small Farmers' Party, Tibor Eckhardt , demanded that he be dismissed because the office was not compatible with Kozma's interests as a shareholder in his media group.

Revisionist and government commissioner in Carpathian Ukraine

Kozma returned to the helm of his media company. In 1938 he secretly organized a Hungarian volunteer corps that was supposed to infiltrate the Carpathian Ukraine in order to cause an uproar there with terrorist attacks. Accompanied by appropriate propaganda, the impression should be created that the Carpathian Ukraine actually wanted to join Hungary, but this will was suppressed militarily. Kozma attached so much importance to the annexation of Cape Ukraine to Hungary because geopolitically he absolutely wanted to achieve a common border with befriended Poland . Even the first action by the poorly equipped paramilitary Rongyos Gárda ("Lumpengarde") against Czechoslovakia in October 1938 ended in disaster. The Czechoslovak Army captured most of the Agents Provocateurs and threatened to execute them if the raids did not stop.

In 1939/40 Kozma organized the deployment of 300 Hungarian volunteers on the Finnish side in the winter war against the Soviet Union . “[T] he Hungarian governments,” he noted, “liked to use me to solve the most delicate tasks, guided by the thought that in view of my well-known friendship and relationships with German, I can also take on things that the Germans see if if someone else would do it, it would be a suspicious thing… ”.

In December 1939 Kozma was appointed Reich Administrative Commissioner for the Carpathian Ukraine, where he had spent several years of his childhood. Here he not only tried to implement an anti-Slav Magyarization policy, but also promised to “solve” the “ Jewish question ”. His statement, formulated in an address to government representatives on May 1, 1941: “What should we do? More brutal measures such as placing them in reserves or throwing them into the water are currently impossible. [...] The Jewish question cannot be resolved seriously and definitively at the moment, but it must be kept up to date until it is resolved after the war, ”according to the protocol, ensured“ general amusement ”among those present.

After the Hungarian entry into the war against the Soviet Union on June 27, 1941, Kozma took up the suggestion of two senior staff members of the Hungarian Aliens Police to deport Jews from Hungary who had been designated as "stateless" to German-occupied territory. He won the support of Chief of Staff Henrik Werth (1881–1952), Defense Minister Károly Bartha (1884–1964), Prime Minister László Bárdossy and finally the cabinet with the exception of Interior Minister Ferenc Keresztes-Fischer (1881–1948) for this project . The execution of the relevant decree of July 12, 1941 was entrusted to Kozma. The aim was to get as many Jews of Polish or Russian origin as possible across the border as quickly as possible. Hungarian Jews who did not have the necessary and extremely difficult to obtain identification papers were also recorded. On this occasion Kozma also had the "wandering gypsies from Transcarpathia" deported. By the end of August 1941, at least 18,000 people had been taken across the border to Kőrösmező and handed over to the SS . Most of them fell victim to the Kamenets-Podolsk massacre there .

The Hungarian historian Ágnes Ságvári therefore sees Kozma as part of a system whose policy aimed at the exclusion of certain ethnic groups and which led to the Holocaust . For Mária Ormos (* 1930), however, Kozma is a symbol of ambivalent conservative reformism in Hungary. He always got into irreconcilable contradictions of moral and political obligations and despaired of them towards the end of his life. Kozma died in 1941 after a brief, serious illness.

Fonts

- Az összeomlás , Budapest, Athenaeum, approx. 1933. (German: The collapse 1918–19)

- Mackensen's Hungarian hussars. Diary of a front officer 1914–1918. Transferred by Mirza v. Schüching, Verlag für Kulturpolitik, Berlin, Vienna 1933. (Original: Egy csapattiszt naplòja 1914–1918 . Budapest 1931)

- Beszédek, előadások 1919-1938 . Budapest no year

- Cikkek, nyilatkozatok 1921-1939 . Budapest 1939.

literature

- Mária Ormos: Egy magyar médiavezér - Kozma Miklós. Pokoljárás a Médiában és a Politikában (1919–1941) . [German “A Hungarian media guide - Miklós Kozma”], 2 vols., PolgART, Budapest 2000 (Magyar közélet) ISBN 963-9306-01-0 .

Web links

- Press clippings in the personal archive of the Leibniz Information Center for Economics

- Films about Miklos Kozma in a collection of Hungarian newsreels

- Newspaper article about Miklós Kozma in the press kit 20th Century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas L. Sakmyster: Hungary's admiral on horseback. Miklós Horthy, 1918–1944 . NY 1994, p. 46.

- ^ Lajos Kerekes: From St. Germain to Geneva. Austria and its Neighbors, 1918–1922. Vienna 1979, p. 195.

- ^ Anikó Kovács-Bertrand: The Hungarian revisionism after the First World War: The journalistic struggle against the peace treaty of Trianon (1918–1931) . Munich 1997, p. 112.

- ^ Iván T. Berend : Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe before World War II. Berkeley 1998, p. 310.

- ↑ Mária Ormos: Hungary in the Age of the Two World Wars, 1914-1945 . NY 2007, p. 258

- ^ Magda Ádam: The Munich Crises and Hungary. The Fall of the Versailles Settlement in Central Europe. In: Igor Lukes, Erik Goldstein (eds.): The Munich Crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II. London 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Tibor Frank (Ed.): Discussing Hitler. Advisers of US Diplomacy in Central Europe, 1934–1941 . Budapest 2003, p. 130.

- ↑ Peter George Stercho: Diplomacy of Double Morality. Europe's Crossroads in Carpatho-Ukraine, 1919-1939. NY 1971, p. 288.

- ↑ Donald Cameron Watt: How War Came. The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938-1939. NY 1989, p. 63.

- ↑ Gábor Richly: "Veriheimolaisemme Tonavan lakeuksilta ovat myös kuulleet sotatorvemme kutsun ...". Hungarian volunteers in the winter war . In: Hungarological contributions 7. Jyväskylä University (1996), p. 128. PDF

- ^ Krisztián Ungváry: The "Jewish question" in social and settlement policy. On the genesis of anti-Semitic politics in Hungary. In: Dittmar Dahlmann, Anke Hilbrenner (ed.): Between great expectations and rude awakening. Jews, Politics and Anti-Semitism in Eastern and Southeastern Europe 1918–1945 . Paderborn 2007, p. 300.

- ↑ Randolph L. Braham : The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary. Detroit 2000, pp. 32f .; János Bársony (Ed.): Pharrajimos. The Fate of the Roma during the Holocaust . NY 2008, p. 33.

- ^ The Holocaust in Carpatho-Ruthenia , chapter 2.

- ↑ Balázs Trencsényi u. Péter Apor: Fine-Tuning the Polyphonic Past. Hungarian Historical Writing in the 1990s. In: Sorin Antohi, Balázs Trencsényi, Péter Apor (eds.): Narratives Unbound: Historical Studies in Post-Communist Eastern Europe. Budapest 2007, p. 41f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kozma, Miklós |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Kozma de Leveld, Miklós; Kozma, Nikolaus von; Vitéz leveldi Kozma Miklós |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Hungarian officer, media entrepreneur and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 5, 1884 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nagyvárad , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 8, 1941 |

| Place of death | Ungvár , Hungary |