Natori

| Natori-shi 名 取 市 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Geographical location in Japan | ||

|

|

||

| Region : | Tōhoku | |

| Prefecture : | Miyagi | |

| Coordinates : | 38 ° 10 ' N , 140 ° 54' E | |

| Basic data | ||

| Surface: | 100.07 km² | |

| Residents : | 78,796 (October 1, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 787 inhabitants per km² | |

| Community key : | 04207-2 | |

| Symbols | ||

| Flag / coat of arms: | ||

| Tree : | Japanese black pine | |

| Flower : | Peach blossom | |

| town hall | ||

| Address : |

Natori City Hall 80 Aza Yanagida, Masuda Natori -shi Miyagi 981-1292 |

|

| Website URL: | http://www.city.natori.miyagi.jp/ | |

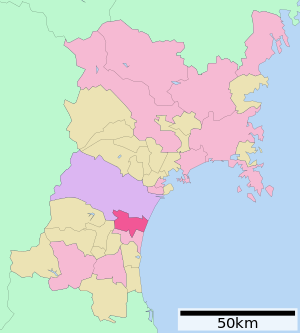

| Location Natoris in Miyagi Prefecture | ||

Natori ( Japanese 名 取 市 , -shi ) is a city in Miyagi Prefecture on Honshū , the main island of Japan .

geography

Natori is located southeast of Sendai and north of Iwanuma in the Sendai plain and consists primarily of low-relief lowlands with agricultural areas ( rice-growing area ) near the Pacific coast. In addition to the rice fields, the flat coastal landscape is characterized by settlements and sandy beaches. The place faces Sendai Bay. Like other cities on the Sendai Plain, it is four kilometers inland from the coastal embankments and breakwaters, just above sea level. The city of Natori has two main population centers: the city center, 5 km from the coast, and the Yuriage district on the coast and adjacent to the mouth of the Natori River.

In the north, the area of Natori is close to the river of the same name, on the right bank of which there is Yuriage with a port and a residential area.

Natori has two coastal regions that include Yuriage. The Yuriage Fishing Port and the Teizan Canal (貞 山 運河 / Teizan-bori ), which runs between the Natori and Abukuma Rivers , are the main topographical features of the city. The Teizan Canal is a transport canal running parallel to the coast from the coast, which Date Masamune (伊達 政 宗), the powerful daimyō from the Tōhoku region, once had excavated.

Also in Natori, in the southern part of the city, at a distance of about one kilometer from the coastline, is Sendai Airport as a connection point to the Tōhoku region.

2011 Tōhoku earthquake

Extent of flooding and damage

On March 11, 2011, 60 minutes after the Tōhoku earthquake , the city was hit by the subsequent tsunami, which also reached places further north 30 minutes after the arrival of the first waves. In Natori, where Sendai Airport is located, a tsunami height of 10-12 m could be measured from the garbage left on trees. The tsunami overturned most of the trees, but the coastal protection forest helped to protect the airport, especially since the tsunami flood depth was only 4 m. After crossing the dams, the tsunami found no restriction in the river valleys and spread over the land surface of the Sendai Plain. The number of completely destroyed residential buildings in Natori is put at 2801.

Although the highest water levels in the Sendai Plain were lower than in the areas further north, a much larger area was flooded. Although a large part of the flood plain was agricultural with a low population density, there were two special exceptions within the city limits with the area of Sendai Airport and with Yuriage, which is located near the Natori River. Yuriage suffered a higher number of casualties than Sendai Airport.

- Yuriage

Yuriage (閖 上, formerly: 閖 上 町) was the most severely damaged district in Natori City. The once economically very lively fishing port with 7,101 inhabitants at the time before the disaster was located directly on and within 800 m of the coast and close to the Natori River. The tsunami rose faster on the river. Its embankments were partially destroyed by the tsunami and in Yuriage suffered breaks at the connections of various structural elements at intervals of around 50 m.

The tsunami reached Yuriage about 65 minutes after the earthquake, flooding the country up to 5.2 km inland, to the vicinity of the embankments of the Tōhoku Expressway ( Tohoku Expressway ) where driving in the tsunami and burning wooden houses, cars, boats and other Debris washed up. The settlement of Yuriage was flooded and hit from different directions by the tsunami, which penetrated from the coast, as well as from the river and the channel that cut off the most exposed area of Yuriage from access to higher ground. In the vicinity of the port, the flood height of the tsunami was 8.81 m. Not only around the harbor, many buildings were destroyed by the tsunami, but also on a small hill, which was the highest country in this area, but was flooded by the tsunami and where the tsunami left a tsunami track at a height of 2.10 m above the highest point of the hill. Thus, no location in the area was high enough for the residents to be evacuated, which is believed to be one of the reasons for the high casualty rate in this area. Few buildings were higher than three stories. Schools were designated as vertical evacuation buildings and often equipped with external stairs to allow easy access.

Over 2902 homes (80 percent of all homes in Yuriage) were partially or completely destroyed. The majority of the buildings on the strip of land between the sea and the Teizan Canal were destroyed by the tsunami. Almost all of the wooden residential buildings in Yuriage collapsed completely. Reinforced and reinforced concrete buildings suffered damage ranging from light to collapse. The reinforced concrete port building and the quay partially collapsed. The tsunami apparently streamed vertically from the east towards the coast and directly into the estuary and over the port of Yuriage, where there were no coastal fortifications worth mentioning.

The Urayasu Nursing Home ( Urayasu Special Elderly Nursing Home , Kozukahara Aza Tohigashi) was largely destroyed by the tsunami. After the tsunami, the area was initially flooded and the nursing home was cut off from the outside world for four days, while most of the houses in the area were washed away. The neighboring rainwater pumping station Yuriage had failed, so that the area could not be drained. 43 of the 163 elderly residents and 4 of the 62 employees died. According to the head of the facility, Keiko Sasaki, the plan to evacuate residents with provisions to a nearby building and wait for help was not implemented after local police instructed staff to bring residents with them shortly before the tsunami Evacuate cars or buses to a local junior high school. The patients were then divided into groups for transportation, but the only route to the destination was crowded and the vehicles got stuck in traffic jams so the tsunami reached them before they got to school. Some patients who survived the tsunami died of hypothermia . On the second day, the staff carried the patients on their backs to another building that had emergency provisions on the higher floors.

Around 752 dead and missing were reported in Yuriage, including the firefighters on duty.

| Area in Yuriage | 1 chome | 2 chome | 3 chome | 4 chome | 5 chome | 6 chome | 7 chome | Kozukahara | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victims (dead and missing) | 49 | 200 | 43 | 84 | 64 | 138 | 89 | 54 | 721 |

| Population (as of 2009) | 667 | 895 | 356 | 755 | 533 | 1062 | 832 | 566 | 5666 |

| Victim rate [%] | 7.3 | 22.3 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 12.7 |

| Share of the population over 75 years of age (as of 2005) [%] | 11.8 | 14.6 | 17.3 | 16.5 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 4.9 | 18.9 | - |

| Share of houses washed away (*) [%] | 21st | 81 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 90 | 91 | - | - |

| (*): The houses washed away were counted using Google maps based on area photos from April 6, 2011 in comparison with the Zenrin house map . | |||||||||

Immediately after the earthquake, the Japanese broadcaster NHK sent a helicopter camera crew to the Sendai coast to broadcast the spread of the tsunami to the coast. The tsunami reached the Sendai coast about an hour after the earthquake and the NHK crew managed to film the moment of the tsunami attack on the coast. The camera team flew along the Natori River and was able to document the advance and emergence of the tsunami along the river. In particular, it filmed the tsunami to the left of the Natori in Sendai-Fujitsuka and to the right of the river in Natori-Yuriage and Natori-Kozukahara. The video has been broadcast worldwide and is included in the NHK video archive. It has been scientifically evaluated and provides important information on the manner in which the tsunami penetrated inland and on its flow characteristics during local flooding.

- Sendai Airport

At Sendai Airport, the tsunami waves broke near the coast and rolled over a 5–10 m high sand dune, whereupon the tsunami flooded rice fields several kilometers inland. The important airport of the Tōhoku region, the Sendai airport located about one kilometer from the coast at an elevation of 4 meters above sea level, was hit by the tsunami. The tsunami hit the airport, flooded the runway, the first floor of the four-story airport terminal building , which was made of steel and reinforced concrete and had a large number of external glazing on all floors, the railway line of the Airport Access Railway . The inner steel frame partition walls of the terminal building were bent by debris. The measured flood heights were 2.82 m inside and 2.98 m outside the airport terminal building. Mud remained in the terminal, but the airport did not damage any structural components. The tsunami flooded the entire area of the airport complex. Many vehicles were destroyed and swept away by the tsunami.

Victim

The fire and disaster control authorities reported 954 dead and 38 missing in Natori.

Measured against the total population of Natori, which was given as 73,134 in the 2010 census, the casualty rate from the 2011 disaster was 1.4% when all dead and missing persons recorded in the 157th FDMA damage report of March 7, 2018 are taken into account or 1.30% if the victims recorded in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016 (954 dead and 39 missing) minus the catastrophe-related deaths reported by the Reconstruction Agency (RA) are taken into account, resulting in a Number of 949 dead and missing results. With the same data base, but based solely on the flood area of the tsunami in Natori, which covered an area of 27 km², the casualty rate was 7.81%. 12,155 people and thus 17% of the total population of the city of Natori (assuming 73,140 inhabitants in 2010) had their residence in the area flooded by the tsunami on March 11, 2011.

The death rate of around 8% was high compared to other areas. As in many other areas of the Tōhoku disaster, most of the victims were older than 65 years.

| Area in Natori | Fatalities | Residents | Tsunami | Distance to the next evacuation site [m] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate [%] | number | Max. Flooding height [m] | Arrival time [min.] | |||

| Yuriage | 13.00 | 705 | 5,424 | 8.81 | 67 | 5,447 |

| Shimomasuda | 5.74 | 71 | 1,238 | 2.98 | 68 | 3,076 |

| Masuda | 0.13 | 10 | 7,759 | 0.24 | 68 | 1,185 |

| Sugigafukuro | 1.45 | 8th | 550 | 2.13 | 68 | 1,242 |

| Source: Total population according to Statistics Bureau (統計局) and Director-General for Policy Planning (政策 統 括 官), 2010 census; Fatalities according to fire and disaster management agency (消防 庁 = Fire and Disaster Management Agency, FDMA); Maximum flood height and arrival time of the tsunami according to The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami Joint Survey Group ; Distance to the nearest evacuation site from the place of residence according to the evacuation site data from the Cabinet Secretariat Civil Protection Portal Site ( http://www.kokuminhogo.go.jp/en/pc-index_e.html ) of the Cabinet Secretariat (内閣 官 房) and the aerial photographs and maps from Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI) from the Tsunami Damage Mapping Team, Association of Japanese Geographers. | ||||||

evacuation

- Designated tsunami evacuation buildings

Four tsunami buildings had been designated as evacuation points by the city council in Natori City: the two-story Yuriage Community Center, the three-story Yuriage Junior High School, the three-story Yuriage Elementary School (名 取 市立 閖 上 小学校) and Sendai Airport in Kitakama. The first three buildings were located outside of the areas previously assessed as a tsunami risk zone and were thus apparently intended more as regular evacuation centers and less specifically for vertical evacuation. Sendai Airport also served as an evacuation site through an existing agreement with the local population for use in the event of a tsunami. These buildings (according to other sources: five buildings in Natori) were the evacuation destination for many people from Yuriage and ultimately served a total of 3,285 evacuees as refuge.

- At the Yuriage Community Center, some water reached the 2nd floor, but 43 people survived in the building.

Yuriage Junior High School and Yuriage Elementary School

- The Yuriage Junior High School (名 取 市立 閖 上 中 学校) building suffered seismic damage to non-load-bearing parts at seismically designed joints, but remained functional as a vertical evacuation building during the tsunami flooding. The school was located 1.5 km from the coast and only 320 m south of the Natori River. The building site on which the school building was located had been raised by 1.8 m to an embankment compared to the surrounding area with rice fields, which reduced the flood height at the eastern end of the school building (facing the ocean) to 1.76 m. The flow velocity was low around the school building. In contrast to other locations, there was only flood damage to the facility, but no rubble blows or damage to the glazing. Around 823 people found refuge in the school during the disaster, who had to stay there for two days after the tsunami. 14 students fell victim to the tsunami. A memorial with the names of all the students killed in the disaster was erected at the entrance to the school. After the school building had initially been placed on the list of candidates for preservation as a disaster ruin, it was finally decided to demolish it.

- The three-story reinforced concrete building of the Yuriage Elementary School, which was only 200 m away from the Yuriage Junior High School, survived the earthquake and was flooded by the tsunami up to the first floor. The school yard was destroyed. Similar to Ishinomaki , where deaths were also caused by the fact that people who had already been successfully vertically evacuated left their place of refuge after the arrival time of the tsunami estimated by the JMA had passed without the tsunami becoming visible, testimonies were also given in the Yuriage primary school According to the parents and children already evacuated the three-storey evacuation building in the direction of the sports hall after the tsunami previously announced by the JMA in Miyagi prefecture at 3 p.m. had not visibly arrived at 3:30 p.m. Meanwhile, the tsunami had reached the northern part of Miyagi Prefecture at the predicted time at 3 p.m. and hit the Yuriage coast by the time over 100 schoolchildren and parents moved from the school building to the gym. After sighting the tsunami, they were able to escape back to the roof of the school building in time. Like many schools, Yuriage Elementary School was equipped with outside stairs to give students, school employees and community members easier access to the designated evacuation site. All those who had fled to the school building were safe after spending a night on the school roof. As in the case of Yuriage Junior High School, Yuriage Elementary School was first placed on the candidate list for preservation as a disaster ruin. Its demolition was later decided and started in early May 2016.

- Similar to the schools in Yuriage, Sendai Airport also served as a vertical evacuation site. Although they warned that a tsunami was expected within 30 minutes and that the airport was within the mapped tsunami flood zone, many did not believe the tsunami warning and the security staff first tried to assign people in the airport to different floors, with such on the first floor was not allowed to move to the floors above. It took two days for helicopters to evacuate passengers and residents stuck in the airport.

| place | Survivors on upper floors | Number of evacuation facilities |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai | 2139 | 4th |

| Natori | 3285 | 5 |

| Ivanuma | 2095 | 5 |

| Watari | 2102 | 5 |

| Yamamoto | 91 | 1 |

| Data source: Iwate Nichi Nichi Shinbun 2011 | ||

In Yuriage, people who were in evacuation buildings left these buildings after the first tsunami waves retreated. The waves that followed later led to the death of many of these people.

- Alternative evacuation sites and escape routes

Other one- or two-story buildings between Yuriage and Sendai Airport, such as a pump house and a university boat club building, were also successfully used for the evacuation. Also on a footbridge in Natori-Yuriage, which is almost 2 kilometers from the sea but less than 500 m from the Natori River and near the Yuriage Bridge (閖 上 大橋), some people survived the tsunami, which caused a flood in this area of about 2 meters by staying on the bridge.

The course of the East Sendai Expressway largely forms the border of the flooded area.

All four buildings designated as evacuation sites in Yuriage were hit by the tsunami. Instead, people fled to the 8-meter high freeway (仙台 東部 道路 / East Sendai Expressway ), which was the only higher-lying terrain in the area. Its embankment served the local residents as an evacuation site and provided safety for 230 people who had fled onto the highway, safe from the tsunami. However, access to the motorway was closed for the inspection of the earthquake damage, which caused traffic jams for those fleeing in their vehicles on the way to the motorway. The East Sendai Expressway , which runs through the Sendai Plain as a 15 mile toll road about 4 km from the coastline on an elevation of 7 to 10 m, acted as a secondary barrier or downstream levee and prevented the tsunami from to advance further inland. In addition, it prevented debris that was washed away from being washed into the urban areas on the landward side.

In the poor relief agricultural plain around Yuriage there is no higher terrain for a distance of several kilometers. Research conducted in Natori found that 65% of residents used a motor vehicle to evacuate them, but this caused traffic jams in Yuriage and put people at risk of being washed away in their vehicles. Many roads led inland via a grid of roads, suggesting a multitude of possible evacuation routes. But all of these roads were single-track, and deep ditches along the roadside prevented one vehicle from being overtaken by another. Therefore, the residents of Yuriage chose the main routes to evacuate with their vehicles.

- Deficiencies in the evacuation system and behavior

Due to blackouts, televisions and telephones failed to transmit tsunami warnings in the city of Natori, while wireless transmission systems were reportedly ineffective there for the same reasons, preventing Natori residents from receiving information that their city was affected by the tsunami. Evacuation impulses were spread via word of mouth, but many people were reluctant to make the decision to evacuate. The evacuation in Natori (as well as in Kesennuma) was apparently impaired by the fact that a major tsunami warning was issued during the earthquake in Chile in 2010 , which then resulted in tsunami heights of 0.5-0.6 m in Kesennuma and 0, 5 m in Natori proved to be wrong. This may have led to the population underestimating the danger and reacted negligently on March 11, 2011, when waves corresponding to a Great Tsunami warning actually reached their city. While young people in Natori are said to have evacuated inland due to the strong ground vibrations, many older residents did not believe that they were in danger from the tsunami, as they had not experienced tsunamis that reached their residential areas (namely: Yuriage) after the previous local earthquake would have.

In the area of Yuriage 2 chome, a little further away from the coast, where 81% of the houses were washed away, the fatality rate of 22% was significantly higher than in areas closer to the fishing port, where 96 to 100% of the houses had fatality rates of 11-12 % were washed away. The cause could be the effect that people who live outside of the areas marked as danger zones on the tsunami risk maps believe they are safe and, compared to people who live in designated danger zones, tend to evacuate late.

According to a study, 57% of the interviewed evacuees were evacuated immediately, but only 57% of the evacuees had decided to evacuate directly because of the natural warning signals. Due to a lack of awareness of the risk of a subsequent tsunami, 30% of residents stayed to clear the earthquake debris and 40% tried to ensure the safety of family members and neighbors instead of evacuating themselves. As a result, 54.5% of those who evacuated with a time delay were evacuated between 20 and 60 minutes after the earthquake. Members of the volunteer fire brigade visited the elderly in their home to convince them to evacuate. While this was successful in some cases, it caused some fire service volunteers to delay their evacuation from the flood zone and were killed by the tsunami. The city of Natori is considered a prime example of a place that suffered damage due to lack of recent tsunami experience and due to underestimation of the tsunami danger through numerical modeling, which on March 11, 2011 led to negligence and delay in evacuation despite existing natural warning signs.

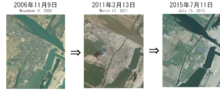

Relocation and Reconstruction

Unlike in other cities such as Iwanuma, resettlement plans for Natori have remained unsettled for a long time due to the conflict between residents who wanted to return to their former neighborhoods and those who did not. Notwithstanding this, Natori planned a new 120-hectare residential area for evacuees after 50 hectares of land were designated as a disaster risk zone on the eastern (sea-facing) and western (land-facing) sides of the Teizan-bori Canal. The plan included a shared resettlement area on 45 hectares of diked land (5 m above sea level) on the western side of the Teizan-bori Canal, although that side of the canal was still part of the area flooded by the March 11 tsunami had been. The homeowners affected by the tsunami on the strip of land between the sea and the Teizan Canal were supposed to move a little further inland to parallel locations, but should not receive any financial support from the state if they wanted to relocate further inland. At the same time, in addition to moving the settlement, there were plans to move the entire settlement, which had been flooded by the Tōhoku tsunami in 2011 at a depth of 3.2 m, by around 3.9 m (residential area) to 4.9 m (protective strip in front of the residential area ) To raise the height and build a higher seawall (6.1 m high) as the first line of protection. The population of Natori preferred to move to higher ground after the disaster, although the local government had recommended that the houses be restored to their original location. Natori City Council failed to reach consensus with parishioners in Yuriage District on a rebuilding program. The majority of the affected people in Yuriage chose not to participate in the program and instead to relocate on their own. The chaotic situation in Natori was due to the minority but politically supported residents who wanted to return to their original residential areas. While 34.1 percent of all residents wanted to “return to their home country” in the summer of 2012, only 25.2 percent expressed their willingness to return in one-on-one discussions that the city held in the spring of 2013.

Reconstruction planning for the Yuriage area was drawn up in November 2013 and elevation work began in autumn 2014.

traffic

The Sendai Airport is located in the cities of Natori and Iwanuma , the south of Sendai are located.

- Street:

- Tōhoku Highway

- National road 4, to Tokyo or Aomori

- National Road 286

- Train:

economy

Neighboring cities and communities

Town twinning

-

Kaminoyama , Japan, since 1978

Kaminoyama , Japan, since 1978 -

Guararapes , Brazil, since 1979

Guararapes , Brazil, since 1979 -

Shingū , Japan, since 2008

Shingū , Japan, since 2008

Personalities

- Riku Danzaki (* 2000), soccer player

- Yūdai Tanaka (born 1995), football player

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dinil Pushpalal: A Journey through the Lands of the Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 14-26 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Stuart Fraser, Alison Raby, Antonios Pomonis, Katsuichiro Goda, Siau Chen Chian, Joshua Macabuag, Mark Offord, Keiko Saito, Peter Sammonds: Tsunami damage to coastal defenses and buildings in the March 11th 2011 Mw9.0 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami . In: Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering . tape 11 , 2013, p. 205-239 , doi : 10.1007 / s10518-012-9348-9 . (Published online March 27, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Lori Dengler, Megumi Sugimoto: Learning from Earthquakes - The Japan Tohoku Tsunami of March 11, 2011 . In: EERI Special Earthquake Report . November 2011, p. 1-15 . Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI).

- ↑ a b c d e Philipp Koch: A Study of the Perceptions of Ecosystems and Ecosystem-Based Services Relating to Disaster Risk Reduction in the Context of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 59-67 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Takahito Mikami, Tomoya Shibayama, Miguel Esteban, Ryo Matsumaru: Field survey of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures . In: Coastal Engineering Journal . tape 54 , no. 1 , 2012, p. 1250011-1-1250011-26 , doi : 10.1142 / S0578563412500118 . (Published March 29, 2012).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1002, Figure 13. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 27.

- ↑ a b Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online July 7, 2012).

- ↑ a b c 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 157 報) ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite )),総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), March 7, 2018.

- ↑ a b Relocation in the Tohoku Area . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 33, pp. 307–315 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b Takashi Seki, Keiko Sasaki, Seiichi Mori, Kenichi Meguro: Use of Traditional East Asian Medicine to Diagnose and Kampo Medicine Kamishoyosan to Treat Survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake 2011: A Retrospective Study . In: Alternative & Integrative Medicine . tape 3 , no. 4 , 2014, p. 172 ff ., doi : 10.4172 / 2327-5162.1000172 . (Published online September 21, 2014).

- ↑ a b c Lessons from Sendai ( Memento August 9, 2018 on WebCite ) , CBC Radio, September 27, 2017.

- ↑ Disaster Information - Pictures taken from Self-Defense Force's helicopter - ( Memento August 10, 2018 on WebCite ) , city.natori.miyagi.jp, March 20, 2011.

- ↑ Disaster Information - Victims found in Natori City - ( Memento from August 10, 2018 on WebCite ) , city.natori.miyagi.jp, September 16, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Isao Hayashi: Materializing Memories of Disasters: Individual Experiences in Conflict Concerning Disaster Remains in the Affected Regions of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology [ 国立 民族 学 博物館 研究 報告 ] . tape 41 , no. 4 , March 30, 2017, p. 337-391 , doi : 10.15021 / 00008472 .

- ↑ a b c H. Murakami, K. Takimoto, A. Pomonis: Tsunami Evacuation Process and Human Loss Distribution in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake - A Case Study of Natori City, Miyagi Prefecture . In: 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering . 2012 ( iitk.ac.in [PDF]).

- ↑ a b Shunichi Koshimura, Satomi Hayashi, Hideomi Gokon: The impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami disaster and implications to the reconstruction . In: Soils and Foundations . tape 54 , no. 4 , August 2014, p. 560-572 , doi : 10.1016 / j.sandf.2014.06.002 . (Published online July 22, 2014).

- ↑ Shunichi Koshimura, Satomi Hayashi, Hideomi Gokon: The impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami disaster and implications to the reconstruction . In: Soils and Foundations . tape 54 , no. 4 , August 2014, p. 560-572 , doi : 10.1016 / j.sandf.2014.06.002 . (Published online July 22, 2014). With reference to the NHK video archive: www9.nhk.or.jp/311shogen/map/#/evidence/detail/D0007030024_00000.

- ↑ 3.11 大 震災, 宮城 県 名 取 市, 3 月 11 日 15 時 54 分 , NHK 東 日本 大 震災 ア ー カ イ ブ ス (NHK Great East Japan Earthquake Archive), program: NHK ニ ュ ー ス (2011 年 3 月 11 日) ( 2011), location: 宮城 県 仙台 市 ・ 名 取 市 名 取 川 上空, video sequences: ニ ュ ー ス 映像, Chapter 1: 3 月 11 日 15 時 54 分, Chapter 2: 3 月 11 日 15 時 58 分, Chapter 3: 3 月11 日 16 時 02 分, Chapter 2: 3 月 11 日 16 時 07 分.

- ↑ a b Mikio Ishiwatari, Junko Sagara: Infrastructure Rehabilitation . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 20, pp. 171–179 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO; here: p. 173, Figure 20.2: "Sendai Airport after the tsunami" ("Source: MLIT").

- ↑ 平 成 22 年 国 勢 調査 - 人口 等 基本 集 計 結果 - (岩手 県 , 宮城 県 及 び 福島 県) ( Memento from March 24, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF, Japanese), stat.go.jp (Statistics Japan - Statistics Bureau , Ministry of Internal Affairs and communication), 2010 Census, Summary of Results for Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, URL: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/index.html .

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online on August 15, 2017), here p. 22, table 2.

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 153 報) ( Memento of March 10, 2016 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 153rd report, March 8, 2016.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 , here: p. 3 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]).

- ↑ Nam Yi Yun, Masanori Hamada: Evacuation Behavior and Fatality Rate during the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Earthquake Spectra . tape 31 , no. 3 , August 2015, p. 1237-1265 , doi : 10.1193 / 082013EQS234M . , here table 2.

- ↑ a b c d e f g S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: pp. 49–51.

- ↑ a b c d Anawat Suppasri: The 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Background, Characteristics, Damage and Reconstruction . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 27-34 .

- ↑ a b c S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 49f, Figure 67.

- ^ A b S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 49f, Figure 66.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 35f.

- ↑ a b c d Surviving the Tsunami - A Film by NHK Japan (approx. 54 minutes), production: NHK, for NOVA / Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), 2011.

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri: The 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Background, Characteristics, Damage and Reconstruction . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 27-34 . Here p. 30f, Fig. 8b

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 36.

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 記録 集 ( Memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), March 2013, here in Chapter 2 (第 2 章 地震 ・ 津 波 の 概要) the subsection 2.2 (2.2津 波 の 概要 (4)) ( PDF ( Memento from March 27, 2018 on WebCite )), p. 63, Fig. 13.

- ↑ Junko Sagara: Multifunctional Infrastructure . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Overview, pp. 49–53 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO; here: p. 50, "Figure 4.1 East Sendai Expressway" "Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT)"

- ↑ a b Junko Sagara: Multifunctional Infrastructure . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Overview, pp. 49–53 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ^ A b S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 33.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: pp. 27, 29.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 28.

- ^ A b S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: pp. 26, 30f.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 31f.

Remarks

- ↑ According to the specifications for tsunami warnings and advisories published by the JMA in 2006, a large tsunami is indicated from an expected tsunami height of three meters for which a message of the category Tsunami Warning: Major tsunami (given here in English) is issued, which contains the shows the predicted tsunami height specifically for each region, namely by means of the five height values 3m, 4m, 6m, 8m or ≥10m. With an expected tsunami height of one or two meters, a tsunami is indicated for which a message of the category Tsunami Warning: Tsunami is issued, which also shows the predicted tsunami height specifically for each region, namely by means of the two height values 1m or 2m. With an expected tsunami height of around half a meter, a tsunami is indicated for which a message of the category Tsunami Advisory with the predicted tsunami height of 0.5 m is issued. Source: S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 8.

Web links

- 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図 , 国土 地理 院 ( Kokudo Chiriin , Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, formerly: Geographical Survey Institute = GSI), www.gsi.go.jp: 地理 院 ホ ー ム> 防災 関 連> 平 成 23 年 (2011年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 に 関 す る 情報 提供> 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図: