Minamisanriku

| Minamisanriku-chō 南 三 陸 町 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Geographical location in Japan | ||

| Region : | Tōhoku | |

| Prefecture : | Miyagi | |

| Coordinates : | 38 ° 41 ' N , 141 ° 27' E | |

| Basic data | ||

| Surface: | 163.74 km² | |

| Residents : | 11,212 (October 1, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 68 inhabitants per km² | |

| Community key : | 04606-0 | |

| Symbols | ||

| Flag / coat of arms: | ||

| Tree : | Machilus thunbergii | |

| Flower : | azalea | |

| Bird : | Golden eagle | |

| Marine animal : | Common octopus | |

| Color : | ██ sky blue | |

| town hall | ||

| Address : |

Minamisanriku Town Hall 77 , Aza Shioiri, Shizugawa Minamisanriku -chō, Motoyoshi-gun Miyagi 986-0792 |

|

| Website URL: | www.town.minamisanriku.miyagi.jp | |

| Location Minamisanrikus in Miyagi Prefecture | ||

Minamisanriku ( Japanese 南 三 陸 町 , - chō ) is a port city in Motoyoshi County , Miyagi Prefecture , Japan .

On March 11, 2011, the city was devastated in large parts by a tsunami as a result of the Tōhoku earthquake .

etymology

The name of the city can be translated as "South Sanriku", where Sanriku is the name of the surrounding region and literally means "three riku ". This riku in turn refers to the former provinces of Rikuō , Rikuchū and Rikuzen , whose former areas spanned the region.

geography

Minamisanriku is located in northeast Miyagi Prefecture along the Pacific Sanriku-Riyal Coast . The area is characterized by its rugged coastline. The emergence and flooding heights of the 2011 tsunami were very high in these rugged coastal areas. The terrain contributed to the intensification of the damage by narrowing the path for the tsunami and directing the tsunami wave for kilometers into the valley.

A large part of the municipality is part of the Kitakami mountainous area , which means that more than 70% of the municipality is forested and the settlement area is mainly only the estuaries. The entire coast is part of the Minamisanriku Kinkazan Quasi National Park for its natural beauty .

The city consists of four districts:

- Utatsu ( 歌 津 ) in the north, where the Isatomae-gawa ( 伊 里 前 川 ) flows into Isatomae Bay ( 伊 里 前 湾 , -wan )

- Shizugawa ( 志 津 川 ) in the east on the northwestern part of Shizugawa Bay ( 志 津 川 湾 , -wan ) in the common estuary of the Mizushiri-gawa ( 水 尻 川 ), Hachiman-gawa ( 八 幡 川 ) and Araita-gawa ( 新 井田 川 )

- Iriya ( 入 谷 ) in a north-western valley of it

- Tokura ( 戸 倉 ) on the southern part of Shizugawa Bay at the mouth of the Oritate-gawa ( 折 立 川 ).

There are also some smaller islands in Shizugawa Bay.

The district of Shizugawa in the Shizugawa Bay opening to the east to the Pacific forms the main part of the city. The shape of Shizugawa Bay is characterized by a 6.6 km wide bay entrance with a total area of the bay of 46.8 km². The actual bay, located within Shizugawa Bay, in which the "city of Minamisanriku" (in the sense of: Shizugawa district) is located and in the 3 river valleys (Mizushiri / 水 尻 川 in the west, Hachiman / 八 幡 川 in the northwest and Araita /新 井田 川 in the northeast) is also broad in shape, opens to the southeast and has a 1.7 km wide bay entrance and a 1.1 km wide harbor entrance. Further inland, the urban developed areas extend up to 1.5 km into the interior.

history

The smaller valleys on the rugged Sanriku Coast were usually home to semi-independent fishing hamlets , whose inhabitants had organized themselves in the past under their own keiyakukai (collective agreements ).

The city was created on October 1, 2005 from the merger of the two communities Shizugawa ( 志 津 川 町 , -chō ) and Utatsu ( 歌 津 町 , -chō ).

Minamisanriku is a thriving fishing town with great aquaculture of silver salmon , scallops, and oysters . Due to their economic importance, damage to these aquaculture facilities caused by tsunamis is a serious problem.

Earthquake and tsunami disasters

| Disaster event | Completely destroyed houses | Death toll | source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meiji 1896 (earthquake and tsunami) | 475 | 1234 | |

| Shōwa 1933 (earthquake and tsunami) | 187 | 85 | |

| Chile 1960 (earthquake and tsunami) | 601 | 38 | |

| Tōhoku 2011 (earthquake and tsunami) | 3167 | 812 | |

| Note: The death toll for the 2011 Tōhoku disaster is calculated from the total number of dead and missing in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016, minus the figures for catastrophe-related deaths determined by the Reconstruction Agency (RA). | |||

Historical tsunami experiences and countermeasures

The Sanriku Coast is an area that has been hit by tsunamis many times in the past. Within one hundred years, three major tsunamis, the Meiji-Sanriku tsunami in 1896 (former community of Shizugawa: 441 dead, 175 houses washed away), the Shōwa-Sanriku tsunami in 1933 (former community of Shizugawa: 22 dead and injured, 7 washed away houses) and the 1960 Chile tsunami (former Shizugawa municipality: 41 dead, 965 houses washed away or destroyed, 5.17 billion yen damage) hit the Tōhoku region, including Minamisanriku. Based on historical experience, the people of Minamisanriku are very much at risk of tsunamis.

After the tsunami triggered by the Chilean earthquake in 1960 , seawalls and tsunami weirs were erected at +4.6 m above mean sea level. Tsunami evacuation exercises were carried out annually. The three rivers traversing the city had been fitted with tsunamis, which could be closed within 15 minutes to prevent tsunamis from penetrating inland upstream via the rivers. In Shizugawa, which suffered severe damage during the Chile tsunami of 1960, memorials were erected to remind residents of the danger of tsunamis. The city showed itself to be completely protected against the tsunami triggered by the Tokachi earthquake in 1968 . On the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the Chile tsunami of 1960, which caused great damage in Minamisanriku, the place received a monument with a bronze sculpture of a condor as the national bird of Chile, from the Chilean government as a gift and a symbol of friendship with Chile, which also had been affected by the disaster. In 1991 a moai statue was completed, which the government of Minamisanriku had asked a Chilean sculptor to make. Both monuments were erected in Matsubara Park in Shizugawa District, where flood markers were also installed. A flood barrier was built near the park and a private residential building was designated as an evacuation site.

In the run-up to the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011, a Miyagi earthquake accompanied by a tsunami was expected in the near future. Thus, in the Shizugawa area, advanced countermeasures in the event of a tsunami had been prepared, such as a tsunami barrier, the maintenance of sanctuaries, careful education of the population about disaster risk reduction, and a voluntary civil protection organization established in 2006 by residents in each neighborhood association. In addition, the residents of Shizugawa only had a tsunami warning as well as a tsunami (with a height of 1) only around a year before the 2011 disaster, the Chile tsunami on February 27, 2010 , in which there were neither victims nor injuries , 30 m in Shizugawa) and experienced the evacuation procedures. A tsunami hazard map for the Shizugawa area was distributed to all households. Both the flood area of the Chile tsunami of 1960 and the slightly smaller expected flood area for the Miyagi tsunami predicted for the near future and 10 evacuation sites were shown. Before the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011, the city of Minamisanriku had earned international recognition for its preparations for a tsunami and was a major excursion destination for tsunami experts.

Tōhoku disaster 2011

Extent of flooding and damage

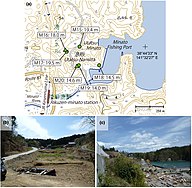

b: Tsunami damage in Utatsu-Namiita (left) and Utatsu-Minato (right)

The tsunami caused by the Tōhoku earthquake on March 11, 2011 hit the population unexpectedly, especially since the first tsunami warning for Miyagi prefecture had predicted a height of three meters. But while the average height of previous tsunamis in Minamisanriku was over 5 m, the maximum height of the 2011 tsunami in the city is stated to be over 10 m for some areas. The height and area of the flood in Minamisanriku far exceeded both the values experienced by the Chiletsunami from 1960 and those based on the predicted Miyagi-ken-oki earthquake (with a magnitude of 7.4 and a repetition interval of less than 40 years ) expected values.

Although the tsunami waves in the bay with downtown Shizugawa were less amplified than in some of the more narrowly shaped rias in other locations, the tsunami height on the coast was estimated at 16 m and at least at Shizugawa Hospital 300 m further inland as at least 11 m captured.

No breakwater had been built at the entrance to Shizugawa Bay, so the tsunami waves could move unhindered towards the city of Shizugawa. The city itself was protected by a large number of protective devices, which mainly consisted of the seawall (or the coastal dikes) and the estuary flood gates (two flood gates that shut off the two rivers concerned). But these were badly damaged or completely destroyed by the tsunami. The concrete pillars of these flood gates remained in place while the steel components attached to them were washed away. Long sections of the tsunami wall collapsed. In fact, the tsunami in Minamisanriku with its flood height of 15.9 m overcame the tsunami weirs and tidal breakwaters unhindered.

Officials had successfully lowered the gates on March 11th, but the floods overcame and undercut the adjacent dykes and could not prevent the city from being flooded. Satellite images of the floodplains showed that the tsunami advanced nearly 3 km up the Hachiman River (八 Fluss 川) and about 2 km into the adjacent river valleys of the Misashirigawa (水 尻 川) in the west and the Niidagawa (新 井田 川) in the east. It flooded an area of 10 square kilometers and 52 percent of the area in the residential areas. Large parts of the city that were less inland were completely destroyed. The number of completely destroyed residential buildings is put at 3,143. An estimated 31 of the 80 designated tsunami evacuation buildings were also damaged, most of them torn away.

Steel skeleton -building suffered heavy damage and it came crashing down several 2- to 3-story reinforced concrete building due to debris impact and / or large-scale washout within 300 meters from the coast. Several large reinforced concrete structures, including vertical evacuation structures, withstood the tsunami but suffered moderate to severe damage. In the area up to 500 m from the shoreline at the port, almost all wood-supported buildings collapsed, and many steel frame and reinforced concrete buildings showed moderate to severe damage.

The Utatsu Ohashi Bridge (or: Utatsu Bridge), a 300 m long and 8.3 m wide prestressed concrete bridge built in 1972 in the Utatsu area , over which National Road 45 ran across Irimae Bay, suffered considerable damage from the tsunami Damage. Most of the bridge's concrete decks were washed away by the tsunami, while none of the supports collapsed. A few years earlier, the bridge had been retrofitted with reinforced concrete cladding for the columns and other protective devices against the collapse of the concrete superstructure deck. A local resident recorded a video on a slope near the end of the bridge leading to Kesennuma on March 11, 2011, which shows the entire rising tsunami progress until the bridge was completely flooded. The tsunami penetrated from two sides. Accordingly, the height of the tsunami at the bridge was 7.2 m. The tsunami flow speed in the middle of the bay was about 6 m / s. The destroyed bridge is a typical example of the type of damage that was seen in many bridges during the Tōhoku disaster. The bridges were designed to withstand earthquake forces , but not for hydrodynamic forces, including lifting forces from tsunamis.

In Utatsu-Namiita and Utatsu-Minato, most of the houses in the lowlands have been torn down or washed away. In the northern settlement a flood height of 18.0 m and two run-up heights of 19.4 and 19.5 m were measured, while in the southern settlement, despite its proximity to the northern one, a lower flood height of 14.6 m and run-up heights of 14.5 m and 14.0 m were measured. In Utatsu-Tanoura, the 2011 tsunami, with heights of 13 to 16 m, was significantly higher than the historical tsunamis (the tsunami heights were 4–11 m in 1896, 5–6 m in 1933, 3 m in 1960 and 1 m in 2010). Almost every home in the low-lying areas was washed away and large amounts of rubble, fishing boats and equipment were carried in the tsunami.

The tsunami memorials in the city of Minamisanriku before the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami for the tsunamis of 1896 ( Meiji-Sanriku tsunami ), 1933 ( Shōwa-Sanriku tsunami ) and 1960 (Chile tsunami) - a 2.6 m high stone monument - were destroyed by the Tōhoku tsunami in 2011. Matsubara Park in Shizugawa was badly damaged. The bronze sculpture of the condor from Chile was lost. The moai statue was also overturned. Her 2 meter head was severed from the statue in the tsunami. but could be found again and taken to the Shizugawa High School grounds . The tsunami signs, which had been installed throughout the city as flood marks to indicate the tsunami height of the Chile tsunami of 1960, were all destroyed by the 2011 tsunami.

The Shizugawa earthquake caused a horizontal displacement of 4.42 m and a subsidence of 0.75 m.

Victim

In the first days of the disaster, mass media reported that 10,000 people (over 50 percent of the population) were missing in the city of Minamisanriku. This news brought the city of Minamisanriku into the focus of public attention, but this information turned out to be misinformation that can be viewed as a result of confusion in the city administration. It was also stated that 95 percent of the city was destroyed by the tsunami.

The Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) reported 514 dead and 664 missing in its 124th damage report on May 19. The number of deaths increased to 620 in the later damage record up to the 157th damage report in 2018, while 211 people were still missing.

Measured against the total population of Minamisanriku, which was given as 17,429 in the 2010 census, the casualty rate from the 2011 disaster was 4.8% if all dead and missing persons recorded in the 157th FDMA damage report of March 7, 2018 are taken into account or 4.66% if the victims recorded in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016 (620 dead and 212 missing) minus the catastrophe-related deaths reported by the Reconstruction Agency (RA) are taken into account, resulting in a Number of 812 dead and missing results. With the same data basis, but based solely on the flood area of the tsunami in Minamisanriku, which covered an area of 10 km 2 , the victim rate was 5.64%, according to other calculations 6.9%. 14,389 people and thus 83% of the total population of the city of Minamisanriku (assuming 17,431 inhabitants in 2010) had their residence in the area flooded by the tsunami on March 11, 2011.

Of the 240 municipal employees in its entire staff, the city lost 39 as dead or missing.

evacuation

In Minamisanriku, the use of vehicles is prohibited both during the tsunami evacuation and during the annual evacuation exercises, which is due to the risk of traffic congestion, the failure of traffic signals during power outages, poor road conditions immediately after an earthquake and the possible rapid consumption of space in evacuation facilities by the Vehicles is justified.

- Evacuation sites

Of the 10 evacuation sites that were recorded in the tsunami hazard map for the Shizugawa area, which had been distributed to all households, 8 were located on a hill, of which only one, located at a slightly lower hill, was covered by the tsunami.

The other two evacuation sites were not on a hill, but in the area flooded by the Chile tsunami in 1960. It was the roof of the Shizugawa Public Hospital and the roof of the Shizugawa Fisheries Cooperative (a four-story building). Both buildings were constructions with a steel frame or made of reinforced concrete. Stable buildings near the coast like these have been designated as "primary refuge" and should, for example, be used as evacuation sites by residents near the coast in the event of an earthquake. However, the tsunami of March 11, 2011 destroyed them all at the same time.

- The 126-bed Public Shizugawa Hospital consisted of two buildings, one with four floors and the other with five floors. The tsunami flooded four floors in both buildings, but did not reach the fifth floor of the five-story building to which many of the hospital's patients and employees had been evacuated. Most of the people who were in the building or who were evacuated into it before the arrival of the tsunami (320) survived on its roof, but 4 employees and 70 patients (according to other data: 71 people in total) died in the building, mostly patients who were unable to escape to the top floor due to illness or weakness. Many patients were saved by being carried up the stairs to the fifth floor by hospital staff before the tsunami hit.

- Despite its low height, the building of the fishing cooperative had only been designated for vertical evacuation with only two floors because it was owned by a public organization that wanted to protect its workers. However, on March 11, 2011, the building was not used for evacuation.

A total of four designated tsunami evacuation buildings were located near the seashore area, which was flooded at a height of 11 m above the ground. In addition to the Shizugawa Hospital and the fishing cooperative, this also included the Takano Kaikan wedding reception building and the Matsubara community apartment block.

- Because the waterfront area was too far from the surrounding hills and there were not enough tall buildings in the area, the city-owned four-story reinforced concrete building of the Matsubara community apartment block near the coastline was specially designed using the guidelines for tsunami evacuation buildings ( Guidelines for Tsunami Evacuation Buildings by the Cabinet Office, Government of Japan = 内閣 府, 2005) was established in 2007 to serve as a tsunami evacuation building for a large number of people from the neighboring sports complex. It had been designated for vertical evacuation. Since the building was constructed after Tusnamie Evacuation Signs were not generally implemented until 2004, the Matsubara Community Apartment Block was the only building with such signs. Initially there were public concerns about its tsunami evacuation function due to its location, but it was agreed that its roof would provide a safe height for evacuation. The backflow of the tsunami of March 11, 2011 destroyed the low seawall that protected the building on the side facing the sea. The building of the Matsubara community apartment block, which was erected lengthways parallel to the harbor line, survived the catastrophe with only minor damage to the load-bearing parts, with the exception of erosion on the sides of the building. However, the tsunami washed over all four floors and also the roof of the building up to a height of around 70 cm, so that a survivor had to take his daughter on the roof to protect her from moisture. A total of 44 people survived on the roof. According to tsunami tracks, the tsunami reached a flood height of at least 14.3 m and according to a witness report 15.4 m.

- On the day of the disaster, the Takano Kaikan wedding reception building in Shizugawa, 160 m inland from the Matsubara community apartment block, around 300 m from Shizugawa Bay and on flat land, offered refuge to around 330 hotel guests and employees who had remained in the building. Most of them were elderly people who had attended a meeting at the time of the earthquake. The quick reaction of the staff saved their lives. Except for its glazing, the building suffered only minor damage, while reinforced concrete structures directly facing the sea collapsed. The Kesennuma-based building owner Abecho Shoten Co. Ltd. intends to keep the building as a disaster ruin. Employees at the Kanyo Hotel in Minamisanriku, one of the Abecho Shoten Co. Ltd. companies, are participating in storytelling activities about the disaster. The building owners had considered making the building available for evacuation purposes as a corporate social responsibility. The high number of survivors made the building next to that of the disaster control center a candidate for a disaster ruin to be preserved.

- Civil Protection Center

In Minamisanriku, a significant part of the transmission of information was done by wireless digital radio systems. For this purpose 105 loudspeakers and wireless radio receivers (type: OKI RV8602) distributed over the whole city were used, which were rented out to all households by the municipal administration. Public offices, schools and factories were also equipped with wireless receivers valued at JPY 50,000 each. The wireless receivers were designed to be in standby mode for most of the time, automatically received Tusnami warnings, and operated from the mains and, in the event of a power failure, from batteries. On March 11, 2011, the tsunami warnings were distributed extremely efficiently through this network.

Due to its age, the government building of the city of Minamisanriku was not considered to be resistant to the expected Miyagi tsunami. Therefore, a temporary government building for disaster control measures had been built, in which the government had set up a specialist unit that had taken over the emergency management department called the "crisis management department". The three-story, 12 m high steel frame building in Shizugawa-Shioirim, which was known as the Government Office for Disaster Prevention , Crisis Management Department (CMD), Municipal building for disaster-prevention or Disaster Management Center , was located in a risk area that was exposed during the Chile- Tsunamis in 1960 was flooded 2.4 m deep. It was built in 1995 as the government building of the former city of Shizugawa and was located about 400 to 500 meters inland from the coast at the port in the event of extensive damage, such as the one in the Chile tsunami of 1960.

This disaster prevention building was destroyed by the tsunami at 3:35 p.m. (according to other sources: 3:25 p.m.), 48 minutes after the earthquake (the time is evidenced by a timestamp photo taken from the roof of the building) and flooded to the roof. The tsunami was 15.5 m high. His arrival interrupted the tsunami warning that was in progress. The staff at this emergency response and tsunami warning center in Minamisanriku broadcast evacuation calls over the radio until the tsunami flooded their building itself. The tsunami flooded the building up to its roof at a height of 10 m above the ground and damaged the building, which however remained standing.

43 people, including residents, visitors from outside the city and 33 staff members were killed in the building. About 30 people sought refuge on the roof. Only ten of the employees (according to other information: 11 people) survived on the roof by clinging to antenna masts on the roof of the building. The remaining 20 (according to other information: about 30) officials or public service employees who had gathered on the roof of the disaster control center during the tsunami were killed. Contrary to what is stated otherwise, the city mayor Jin Sato (佐藤 仁) survived on the roof of the building.

Various stories of the deaths of public employees, officials and volunteer firefighters in the tsunami-struck area were subsequently circulated. City official Miki Endo, who was in charge of the public announcement of emergency information and had stayed at her post on the second floor to continue the announcement, was among the fatalities. She was subsequently credited with saving many people who had heeded her request to take refuge in higher terrain. The voice of this woman, who was reported to have planned her wedding for September 2011, has been described as the "voice of an angel" that, although tinged with fear and concern, has given many people courage.

Only the steel frame of the building survived the tsunami. It has become a memorial to the catastrophe and has subsequently been visited by many people to pray for the victims. City Mayor Sato, who had initially declared his intention to preserve the building, spoke out in favor of demolishing it in September 2013 due to the maintenance costs. However, in December 2013, Miyagi Prefecture added the building to the 14-candidate list for investigation as Miyagi disaster ruins, and the city's decision to demolish it was suspended. A meeting of experts on disaster ruins in December 2014 attributed considerable value to maintaining the building as a disaster ruin. The building will serve as the Miyagi Prefecture building until 2031, which will cover maintenance and operating costs for the city, postponing the decision to keep or demolish the building.

reconstruction

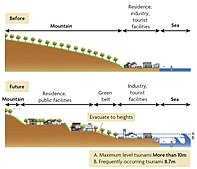

A: Flood level of a tsunami of the highest level (over 10 m height)

B: Flood level of more frequent tsunamis (8.7 m height)

Among the community employees of the community who lost their lives in this building were those who were supposed to lead the reconstruction after a disaster, so that the functionality of the administration was largely paralyzed.

Similar to the prefectural reconstruction planning process, Japanese communities set up reconstruction planning committees after the 2011 disaster that included experts, residents and community officials. These typically used surveys and workshops to incorporate residents' opinions into the plans. In Minamisanriku, a residents' committee played a key role in proposing "symbolic projects" that were then incorporated into the city's reconstruction plan. The Japanese communities tried to reach a consensus for the reconstruction strategy through the zoning plan. The zoning plan was based on tsunami simulations carried out by the prefectural governments for two different levels of tsunamis: On the one hand, for a level 1 tsunami, which will occur with a relatively high statistical probability (once in 100 or fewer years) and cause significant damage . On the other hand, for a tsunami of the highest level (level 2, this also includes the Tōhoku tsunami 2011), which has a lower statistical probability (only about once every 1,000 years), but carries the risk of devastating destruction. The coastal seawalls were usually designed in height for the more frequent tsunamis, while they could be inundated by tsunamis of the highest level and thus the city could be inundated. The zoning plans included measures such as relocation of residential areas, land elevation and multiple protection through forests and / or roads, which were supposed to limit the flood level in the residential areas to less than 2 meters, so that the houses were unlikely to be washed away. Low-lying areas should be reserved for parks, trade and industry, as was the case in the reconstruction concept of the city of Minamisanriku. For a tsunami of the highest level (flooding at the maximum level) the evacuation of the residents was necessary, so that early warning systems and escape routes were of crucial importance. In the coastal areas of the northern part of Miyagi Prefecture with Minamisanriku - as in Iwate Prefecture - there was not enough land available for resettlement, as the coast is lined with soaring mountains. As a result, many coastal fishing villages in the city of Minamisanriku were badly hit by the 2011 tsunami and had to be relocated. However, since the residents wanted to live close to their hometown and the fishing port to secure their livelihoods, a separate resettlement policy was proposed, in which each village moved to a small hillside location near its original location.

About a year after the disaster, the makeshift shopping street Minamisanriku Sun Sun Shopping Village opened near the disaster relief center destroyed by the tsunami. After the Chilean President, Sebastián Piñera , had promised the city of Minsamisanriku a larger and stronger statue during a visit to Minamisanriku in March 2012, he presented a new Moai statue that was five meters high and weighed 6 tons together with its base at Christmas 2012 , to replace the old one that was destroyed in the 2011 tsunami. City Mayor Jin Sato said earlier in the year that people loved the old statue, which was a "symbol of reconstruction." The new statue was carved out of stone specifically for the purpose on Easter Island . It has since been exhibited in Tokyo and later set up in Minamisanriku at the Minamisanriku Sun Sun Shopping Village .

In the Minamisanriku region, most of the people could no longer settle in the coastal plain. The question of how the extensive areas, which were no longer designated as residential areas but as endangered, could be used, posed a decisive problem. Alternative forms of use for such areas remained unclear. Most Japanese local governments planned to use them for parks, tourism (development of facilities such as souvenir shops and restaurants ) and fishing (development of fish processing plants and related facilities) in such cases, while some local governments were considering developing renewable energy projects . to solar and wind energy to produce.

According to government statistics, population movements occurred after the 2011 disaster, with large numbers of people moving out of the affected communities. The gap between emigrants and immigrants in relation to the total population in 2011 was particularly high for coastal communities, with Minamisanriku showing a particularly high gap with 9.4% (before Yamamoto with 8.9% and Ōtsuchi with 8.5%). This gap was also large among young people (younger than 15 years old), again particularly in Minamisanriku with 14.6% (even before Onagawa with 13.2%), which also increased concerns about the aging of the population . In Minamisanriku, some residents gave up reconstruction completely due to a lack of funds and planned either to leave the city or to move into public housing.

traffic

Minamisanriku is connected to the rail network by the JR East Kesennuma Line to Maeyachi in Ishinomaki or to Kesennuma . The main train station is Shizugawa. Highways are the national roads 45 to Sendai or Aomori and 398 to Ishinomaki or Yurihonjō .

education

Minamisanriku has five elementary schools, four middle schools, and the Shizugawa Prefectural High School.

Town twinning

Minamisanriku has had a domestic partnership with Shōnai since May 17, 2006 . This goes back to a friendship between the former Utatsu and Tachikawa , which rose in Shōnai in October 1968 .

Movie

- Minamisanriku - Fate of a City (Germany, 2012, 52 min., Online at arte.tv)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Dinil Pushpalal: A Journey through the Lands of the Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 14-26 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Takahito Mikami, Tomoya Shibayama, Miguel Esteban, Ryo Matsumaru: Field survey of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures . In: Coastal Engineering Journal . tape 54 , no. 1 , 2012, p. 1250011-1-1250011-26 , doi : 10.1142 / S0578563412500118 . (Published March 29, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Stuart Fraser, Alison Raby, Antonios Pomonis, Katsuichiro Goda, Siau Chen Chian, Joshua Macabuag, Mark Offord, Keiko Saito, Peter Sammonds: Tsunami damage to coastal defenses and buildings in the March 11th 2011 Mw9.0 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami . In: Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering . tape 11 , 2013, p. 205-239 , doi : 10.1007 / s10518-012-9348-9 . (Published online March 27, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Anawat Suppasri, Abdul Muhari, Fumihiko Imamura: Minami - Sanriku town field trip (17 March 2013) ( Memento from 6 August 2018 on WebCite ) , Internet presentation of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science, Tohoku Universitay (IRIDeS), Tsunami Engineering Laboratory,> Member> Hazard and Risk Evaluation Research Division - Tsunami Engineering: Anawat SUPPASRI (Associate Professor) ( Suppasri Anawat ( Memento August 6, 2018 on WebCite ))> The 2011 Tohoku tsunami field guide: Minami-Sanriku. [Without a date]. Publication without peer review .

- ↑ a b c d e f Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online August 15, 2017). With reference to: Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Forensic investigation of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster: a case study of Rikuzentakata , Disaster Prevention and Management, 26 (3) (2017), pp. 298-313 , doi: 10.1108 / DPM-10-2016-0213 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sekine, Ryohei: Did the People Practice "Tsunami Tendenko"? -The reality of the 3.11 tsunami which attacked Shizugawa Area, Minamisanriku Town, Miyagi Prefecture- ( Memento April 21, 2018 on WebCite ) , tohokugeo.jp (The 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association), June 13, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online July 7, 2012).

- ↑ 旧志 津 川 町 の 年表 【明治】 (明治 28 年 ~) ("Chronicle of the earlier Shizugawa (from 1895)"). Minamisanriku, February 19, 2010, accessed August 13, 2016 (Japanese).

- ↑ 旧志 津 川 町 の 年表 【昭和】 (~ 昭和 30 年) ("Chronicle of the former Shizugawa (until 1955)"). Minamisanriku, June 24, 2010, accessed August 13, 2016 (Japanese).

- ↑ 旧志 津 川 町 の 年表 【昭和】 (昭和 31 年 ~) ("Chronicle of the former Shizugawa (from 1956)"). Minamisanriku, February 19, 2010, accessed August 13, 2016 (Japanese).

- ↑ 津 波 ハ ザ ー ド マ ッ プ (南 三 陸 (志 津 川)) . (No longer available online.) Miyagi Prefecture, Oct. 1, 2010, archived from the original on Feb. 18, 2013 ; Retrieved August 13, 2016 (Shizugawa flood maps for Valdivia 1960 earthquake (yellow) and hazard (red)).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lori Dengler, Megumi Sugimoto: Learning from Earthquakes - The Japan Tohoku Tsunami of March 11, 2011 . In: EERI Special Earthquake Report . November 2011, p. 1-15 . , Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI).

- ↑ a b c d e f Moai “Living for the future” - “Connect with the bonds of friendship across the distant Pacific Ocean.” ( Memento from August 14, 2018 on WebCite ) , m-kankou.jp, [undated].

- ↑ a b c d New moai statue sent to Japan from Chile a gift of hope ( Memento from August 14, 2018 on WebCite ) , thisischile.cl, April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Nobuhito Mori, Daniel T. Cox, Tomohiro Yasuda, Hajime Mase: Overview of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami Damage and Its Relation to Coastal Protection along the Sanriku Coast . In: Earthquake Spectra . tape 29 , S1, 2013, pp. 127-143 , doi : 10.1193 / 1.4000118 .

- ↑ Alison Raby, Joshua Macabuag, Antonios Pomonis, Sean Wilkinson, Tiziana Rossetto: Implications of the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami on sea defense design . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 14 , no. 4 , December 2015, p. 332-346 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2015.08.009 . (Published online September 14, 2015). Published under a Creative Commons License (CC BY 4.0: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1001, Figure 11. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (Published online March 19, 2014). License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3190, Figure 8.

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1015, Figure 31. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ a b Nobuo Mimura, Kazuya Yasuhara, Seiki Kawagoe, Hiromune Yokoki, So Kazama: Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami - A quick report . In: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change . tape 16 , no. 7 , 2011, p. 803-818 , doi : 10.1007 / s11027-011-9304-z . (Published online May 21, 2011).

- ↑ Earthquake in Japan: The Day After the Tsunami. In: Spiegel Online. March 12, 2011, Retrieved March 17, 2011 (post-image by Shizugawa, Minamisanriku).

- ↑ a b c 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 157 報) ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite )),総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 157th report, March 7, 2018.

- ↑ Tsunami hit more than 100 designated evacuation sites. (No longer available online.) In: The Japan Times Online. April 14, 2011, archived from the original on September 8, 2011 ; accessed on August 13, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Hamed Salem, Suzan Mohssen, Kenji Kosa, Akira Hosoda: Collapse Analysis of Utatsu Ohashi Bridge Damaged by Tohuku Tsunami using Applied Element Method . In: Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology . tape October 12 , 2014, p. 388-402 , doi : 10.3151 / jact.12.388 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Li Fu, Kenji Kosa, Hideki Shimizu, Zhongqi Shi: Damage Judgment of Utatsu Bridge Affected by Tsunami due to Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Journal of Structural Engineering . 58A, March 2012, p. 377-386 , doi : 10.11532 / structcivil.58A.377 .

- ↑ a b c d K. Kawashima, H. Matsuzaki: Damage of Road Bridges by 2011 Great East Japan (Tohoku) Earthquake , Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Paper No. 683, Lisbon / Portugal, 2012 (conference report without peer review ).

- ↑ Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku and Previous Great Earthquakes . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (First published online on March 19, 2014). License: Creative Commons Attribution License.

- ↑ a b c d e Chile replaces Japanese town's headless statue ( memento August 6, 2018 on WebCite ) , taipeitimes.com, December 26, 2012 (AFP).

- ↑ 宮城 ・ 南 三 陸 町 で 75 セ ン チ 地盤 沈下 国土 地理 院 「過去 過去 最大 の 沈下」 . (No longer available online.) In: MSN 産 経 ニ ュ ー ス . Sankei Shimbun, March 14, 2011, archived from the original on November 22, 2013 ; Retrieved August 13, 2016 (Japanese).

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 124 報) ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 124th report, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . (No longer available online.) In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, May 20, 2011, archived from the original on June 19, 2011 ; Retrieved June 19, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . (No longer available online.) In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, April 10, 2011, archived from the original on May 1, 2011 ; Retrieved May 1, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

- ↑ 平 成 22 年 国 勢 調査 - 人口 等 基本 集 計 結果 - (岩手 県 , 宮城 県 及 び 福島 県) ( Memento from March 24, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF, Japanese), stat.go.jp (Statistics Japan - Statistics Bureau , Ministry of Internal Affairs and communication), 2010 Census, Summary of Results for Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, URL: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/index.html .

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online on August 15, 2017), here p. 22, table 2.

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 153 報) ( Memento of March 10, 2016 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 153rd report, March 8, 2016.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 3.

- ↑ Supporting and Rmpowering Municipal Functions and Staff . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 17, pp. 149–153 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Protecting Significant and Sensitive Facilities . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 5, pp. 55–62 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 32.

- ↑ a b c Akemi Ishigaki, Hikari Higashi, Takako Sakamoto, Shigeki Shibahara: The Great East-Japan Earthquake and Devastating Tsunami: An Update and Lessons from the Past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923 . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 229 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 287-299 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.229.287 . Here p. 291, Fig. 4 "Sorrowful remnants of the tsunami attack in Minami-Sanriku".

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 45ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Akemi Ishigaki, Hikari Higashi, Takako Sakamoto, Shigeki Shibahara: The Great East-Japan Earthquake and Devastating Tsunami: An Update and Lessons from the Past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923 . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 229 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 287-299 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.229.287 . (Published online April 13, 2013).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Isao Hayashi: Materializing Memories of Disasters: Individual Experiences in Conflict Concerning Disaster Remains in the Affected Regions of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology [ 国立 民族 学 博物館 研究 報告 ] . tape 41 , no. 4 , March 30, 2017, p. 337-391 , doi : 10.15021 / 00008472 .

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 29f.

- ↑ a b c Stephanie Chang et al .: The March 11, 2011, Great East Japan (Tohoku) Earthquake and Tsunami: Societal Dimensions . In: EERI Special Earthquake Report . August 2011, p. 1-23 . Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI).

- ↑ 安 否 不明 の 町 長生 還 骨 組 み だ け の 庁 舎 で 一夜 宮城 ・ 南 三 陸 . Kahoku Shimpo. March 14, 2011. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Akemi Ishigaki, Hikari Higashi, Takako Sakamoto, Shigeki Shibahara: The Great East-Japan Earthquake and Devastating Tsunami: An Update and Lessons from the Past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923 . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 229 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 287-299 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.229.287 . (Published online April 13, 2013). With reference to: 防災 対 策 庁 舎 の 悲劇 ◆ 宮城 ・ 南 三 陸 ( memento from August 15, 2018 on WebCite ) , memory.ever.jp, [undated].

- ↑ International Recovery Platform, Yasuo Tanaka, Yoshimitsu Shiozaki, Akihiko Hokugo, Sofia Bettencourt: Reconstruction Policy and Planning . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 21, pp. 181–192 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books ). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Here: p. 185, "Figure 21.4 Recovery concept of Minamisanriku Town - Source: Minamisanriku Town.".

- ↑ International Recovery Platform, Yasuo Tanaka, Yoshimitsu Shiozaki, Akihiko Hokugo, Sofia Bettencourt: Reconstruction Policy and Planning . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 21, pp. 181–192 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books ). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Here: p. 188, "Map 21.3 Land-use planning and projects in Minamisanriku - Source: Minamisanriku Town.".

- ↑ a b c d e International Recovery Platform, Yasuo Tanaka, Yoshimitsu Shiozaki, Akihiko Hokugo, Sofia Bettencourt: Reconstruction Policy and Planning . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 21, pp. 181–192 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books ). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ^ A b Maki Norio: Long-Term Recovery from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster . In: V. Santiago-Fandiño, YA Kontar, Y. Kaneda (Ed.): Post-Tsunami Hazard - Reconstruction and Restoration (= Advances in Natural and Technological Hazards Research (NTHR, volume 44) ). Springer, 2015, ISBN 978-3-319-10201-6 , ISSN 1878-9897 , chap. 1 , p. 1-13 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-319-10202-3 . (Published online 23 September 2014).

- ↑ a b Mikio Ishiwatari, Junko Sagara: Structural Measures Against Tsunamis . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 1, pp. 25–32 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Kenzo Hiroki: Strategies for Managing Low-Probability, High-Impact Events . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 32, pp. 109–115 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Tsunami hit Minamisanriku gets Kuma-designed shopping center , japantimes.co.jp, March 3, 2017.

- ↑ The Moai of Minamisanriku - Remembrance, Resilience, Souvenir ( Memento August 14, 2018 on WebCite ) , en.japantravel.com, August 12, 2015, by Justin Velgus.

- ↑ Michio Ubaura, Akihiko Hokugo, Mikio Ishiwatari, International Recovery Platform: Relocation in the Tohoku Area . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 33, pp. 307–315 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books ). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Remarks

- ↑ a b With regard to reports in the mass media and in particular on television about the disaster of 2011 in the Minamisanriku community, it should be noted that although these reports often referred to the "city of Minamisanriku", the majority refer to the central-southern part ( formerly the city of Shizugawa) and not related to the northern one (formerly the city of Utatsu). (Source: Sekine, Ryohei: Did the People Practice "Tsunami Tendenko"? -The reality of the 3.11 tsunami which attacked Shizugawa Area, Minamisanriku Town, Miyagi Prefecture- ( Memento from April 21, 2018 on WebCite ) , tohokugeo.jp (The 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association), June 13, 2011.)

- ↑ These tsunami memorials in Shizugawa, erected after the Chile tsunami of 1960, were then destroyed by the Tōhoku tsunami of March 11, 2011. (Source: Takahito Mikami, Tomoya Shibayama, Miguel Esteban, Ryo Matsumaru: Field survey of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures . In: Coastal Engineering Journal . Volume 54 , no. 1 , 2012, p. 1250011-1-1250011-26 , doi : 10.1142 / S0578563412500118 . )

- ↑ According to the specifications for tsunami warnings and advisories published by the JMA in 2006, a large tsunami is indicated from an expected tsunami height of three meters for which a message of the category Tsunami Warning: Major tsunami (given here in English) is issued, which contains the shows the predicted tsunami height specifically for each region, namely by means of the five height values 3m, 4m, 6m, 8m or ≥10m. With an expected tsunami height of one or two meters, a tsunami is indicated for which a message of the category Tsunami Warning: Tsunami is issued, which also shows the predicted tsunami height specifically for each region, namely by means of the two height values 1m or 2m. With an expected tsunami height of around half a meter, a tsunami is indicated for which a message of the category Tsunami Advisory with the predicted tsunami height of 0.5 m is issued. Source: S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 8.

- ↑ One problem can be seen in the way in which the Japan Meteorological Agency issued the major tsunami warning. The TV broadcaster NHK had broadcast a major tsunami warning on March 11, 2011 at 3:03 p.m., stating that shortly before 3 p.m. in the town of Ishinomaki- Ayukawa (石 巻 鮎 川), just south of Shizugawa, a tsunami height of 50 cm and in the port of the city of Ōfunato (大船 渡 港), just north of Shizugawa, of 20 cm. The announcement was also broadcast over the radio and may have caused people to evacuate late. On the other hand, there was a large-scale power failure immediately after the earthquake, so that many people should not have seen or heard this message. (Source: Sekine, Ryohei: Did the People Practice "Tsunami Tendenko"? -The reality of the 3.11 tsunami which attacked Shizugawa Area, Minamisanriku Town, Miyagi Prefecture- ( Memento from April 21, 2018 on WebCite ) , tohokugeo.jp (The 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association), June 13, 2011.)

Web links

- 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図 , 国土 地理 院 ( Kokudo Chiriin , Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, formerly: Geographical Survey Institute = GSI), www.gsi.go.jp: 地理 院 ホ ー ム> 防災 関 連> 平 成 23 年 (2011年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 に 関 す る 情報 提供> 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図: