Valdivia earthquake in 1960

| Valdivia earthquake in 1960 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| date | May 22, 1960 | |

| Time | 3:11 p.m. local time (7:11 p.m. UT ) | |

| intensity | XI - XII on the MM scale | |

| Magnitude | 9.5 M W | |

| depth | 33 km | |

| epicenter | 38 ° 17 ′ 24 ″ S , 73 ° 3 ′ 0 ″ W | |

| country | Chile | |

| Tsunami | Yes | |

| dead | 1655 | |

| Injured | 3000 | |

| damage | US $ 880 million | |

The Valdivia earthquake on May 22, 1960, also known as the Great Chile Earthquake , was a megathrust earthquake with the largest magnitude ever recorded in the world and the heaviest earthquake of the 20th century. At 3:11 p.m. local time (19:11 UT ) the quake reached a value of M w 9.5 on the moment magnitude scale . The topographical shape of large areas of the Little South of Chile was changed, the area around the provincial capital Valdivia was particularly affected .

The earthquake triggered a tsunami that wreaked havoc across the Pacific . An estimate by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) is around 1,655 dead, 3,000 injured and two million homeless.

Tectonic background

Like all of Chile, the area affected by the Great Chile Earthquake is located in the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire , a zone of high seismic and volcanic activity that extends around the Pacific Ocean . Strong earthquakes are therefore not uncommon in the coastal regions of Chile, and the country is even one of the areas most severely affected by earthquakes in the Circumpacific region.

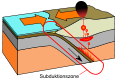

Chile is located on the western edge of the South American Plate , on the converging plate boundary with the oceanic Nazca Plate . The two plates move about 63 millimeters towards each other on average every year, the Nazca plate is subducted under the continental plate . The tensions occurring in the underground discharge in strong earthquakes. Since 1950, 28 earthquakes with a minimum magnitude of 7 have occurred in Chile, the last on September 17, 2015, with a magnitude of 8.3.

The Nazca plate is subducted under the South American plate

course

The Great Chile Earthquake was the culmination of a whole series of earthquakes that shook central southern Chile within a few days. Scientists from the Universidad de Chile spoke of the "worst series of earthquakes that has ever been observed in Chile".

The tremors started on the morning of May 21 at Curanilahue and Concepción . The tremors, each with a strength of M W 7.25, interrupted the traffic and telephone connection from the capital Santiago to the south of the country and triggered numerous fires. President Jorge Alessandri canceled his participation in the traditional celebrations to commemorate the Battle of Iquique in 1879 in order to gain an overview of the damage and relief measures on the spot.

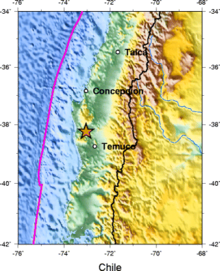

The organization of the relief measures for the area around Concepción had just started when another violent earthquake further south shook the area around Valdivia on the afternoon of the following day. About half an hour later, at 3:11 p.m. local time, the worst earthquake ever recorded followed. It lasted four minutes and rocked Chile between Talca and the island of Chiloé .

In the days after the main quake, hundreds of aftershocks occurred in the region, eleven of them 6 to 7 magnitude alone.

Tectonic interpretation

The earthquake is one of the so-called megathrust earthquakes . The earth's crust broke over a length of around 1000 kilometers between Lebu and Puerto Aisén ; a 200-kilometer-wide block of the earth's crust between the continental margin and the Andes was jerked 20 meters to the west and tilted in the process. The crack speed (the speed at which the front of a crack moves in the earth's crust in an earthquake) was 3.5 km / s.

The exact location of the epicenter is controversial. The USGS refers to the Japanese geophysicist Hiroo Kanamori , who in 1977 determined the coordinates 38.29 ° south latitude and 73.05 ° west longitude, a position northwest of the city of Temuco . The hypocenter of the main quake was at a depth of 33 kilometers.

An energy of over eleven trillion (11.2 × 10 18 ) joules was released - this corresponds to an explosion of 180 gigatons (TNT equivalent) . The shock caused the earth's axis to shift three centimeters.

Direct damage from the earthquake

According to different estimates, one to two million Chileans were left homeless as a result of the quake and tsunami, which corresponds to up to a quarter of the total population of the country at the time. The Chilean government put the number of destroyed buildings at 58,622. The fact that only a few hundred people died as a result of the earthquake itself, and therefore comparatively few people for an earthquake of this magnitude, is attributed, among other things, to the advance warning from the weaker earthquakes immediately preceding.

The severity of the building destruction mainly depended on geological conditions such as the respective subsoil. In Valdivia, buildings in the west of the city suffered far more, as the subsurface here is less stable than in the east and moves more strongly in the event of an earthquake. Buildings erected on artificial fillings were particularly hard to destroy. Soil liquefaction occurred there during the earthquake . Brick buildings were also far more affected by destruction than modern reinforced concrete buildings or traditional wooden houses.

The subjective strength of an earthquake, the intensity, is usually represented by a value on the Mercalli scale . The geographer Wolfgang Weischet , who was working at the Universidad Austral de Chile in Valdivia at the time of the quake, estimated the intensity of the destruction in Valdivia to be X ("destructive"), while in the villages of Corral and Hueyelhue, which are only 20 kilometers away and on more stable ground only the Mercalli level VII ("very strong") was achieved.

Besides Valdivia, the village of Puerto Octay on Lake Llanquihue was the place with the highest earthquake intensity. Here was the center of an area of particularly high intensity that stretched in the Chilean central valley in the form of an ellipse in a north-south direction. The port of the city of Puerto Montt in the south of this area was also badly damaged.

In the Andes , on cliffs and in the lake area of the Little South from Lago Villarica to Lago Todos los Santos , the earthquake caused several landslides .

| May 21 earthquake | ||

|---|---|---|

| place | Mercalli level | Damage |

| Concepción | IX | 125 dead, many buildings destroyed |

| Talcahuano | IX | 65% of all buildings destroyed |

| Coronel | IX | |

| Lota | IX | |

| Lebu | X | |

| May 22nd earthquake | ||

| place | Mercalli level | Damage |

| Valdivia | X | 40% of all buildings destroyed |

| Puerto Montt (Lower Town) | X-XI | 90% of all buildings destroyed |

| Río Negro | IX-X | |

| Temuco | VIII | |

| Osorno | VII-VIII | |

| Puerto Saavedra | VII-VIII | completely destroyed by the tsunami |

| Llanquihue | VII-VIII | |

| Villarrica | VII | |

Triggered natural disasters and consequential damage

The tsunami

| place | Coordinates | A. |

|---|---|---|

| Isla Mocha , Chile | 38.22 ° S 74.00 ° W | 25 m |

| Valdivia , Chile | 39.80 ° S 73.24 ° W | 10 m |

| Ancud , Chile | 41.91 ° S 72.76 ° W | 12 m |

| Puerto Saavedra , Chile | 38.78 ° S 73.40 ° W | 9 m |

| Arica , Chile | 18.47 ° S 70.32 ° W | 2.2 m |

| Easter Island , Chile | 27.15 ° S 109.45 ° W | 6 m |

| Hilo , Hawaii | 19.73 ° N 155.06 ° W | 10.7 m |

| Apia , Samoa | 13.81 ° S 171.75 ° W | 4.9 m |

| Eden , Australia | 37.05 ° S 149.97 ° E | 1.7 m |

| Hong Kong | 22.30 ° N 114.18 ° E | 0.5 m |

| Mutsu , Japan | 41.31 ° N 141.23 ° E | 6.3 m |

| Hokkaidō , Japan | 42.90 ° N 145.00 ° E | 5.0 m |

| Pismo Beach , USA | 35.14 ° N 120.66 ° W. | 2.4 m |

The earthquake temporarily lowered the coastline at Valdivia by up to four meters, causing a tidal wave up to 25 meters high that devastated the Chilean coast and spread as a tsunami across the entire Pacific Ocean.

Numerous ships sank or ran aground in the port of Valdivia and off the Chilean coast. In the bay of Valdivia, the seabed fell dry for almost an hour before the sea burned back in a ten-meter-high wave. Quite a few people were killed who searched the seabed for crabs.

Hilo , Hawaii , 10,000 kilometers away , where the tidal wave still reached an amplitude of eleven meters, and coastal regions of Japan , the Philippines and Kamchatka were devastated. Even California , the Easter Island and Samoa were affected.

The tsunami is responsible for the majority of the earthquake's deaths. Outside Chile, the tsunami killed 138 people in Japan, 61 in Hawaii and 32 in the Philippines.

Temporal spread (line spacing corresponds to 1h) of the tsunami over the Pacific.

Isla Mocha : After the tsunami hit, a ship ran aground. Numerous landslides can be seen on the cliffs.

The almost completely destroyed center of Corral - photo from autumn 1960.

Floods on Lake Riñihue

The earthquake triggered landslides on numerous slopes . Three large landslides on Mount Tralcán spilled the outflow of Lake Riñihue with the Río San Pedro , so that the water level of the lake rose by up to 20 meters as a result.

Already after the earthquake in 1575 a comparable event had occurred at this point. At that time, the natural dam finally broke after several months, and the tidal wave washed away the Mapuche settlements along the Río San Pedro and the Río Calle-Calle and caused severe damage in the Spanish colony of Valdivia.

In order to prevent a repetition of this disaster called Riñihuazo , which would have affected around 100,000 people in the area of influence of the river, a rescue operation was started to remove the dams up to 24 meters high. Within a month, with the help of thousands of soldiers and workers as well as 27 bulldozers, the height of the dams was reduced to 15 meters each, so that the pent-up water could drain away on June 23rd. The following tsunami continued to cause flooding and destruction in numerous towns along the river; But people were not harmed.

volcanic eruptions

The quake triggered a rhyodacic fissure eruption of the Puyehue-Cordón-Caulle volcanic complex two days later. The eruptions from a 300 meter long crevice hurled ash up to six kilometers high into the atmosphere and lasted until July. There was ash rain for days in the central Chilean valley , but the outbreak did not cause any significant damage.

In the months that followed, volcanic activity in Chile was greatly increased; a total of five volcanic eruptions were recorded. For a long time this was thought to be a coincidence; In 2007, however, geologists proved the connection between volcanic eruptions and particularly strong earthquakes. Accordingly, after earthquakes with a magnitude of 9 or more, volcanoes that have been inactive for a long time erupt, in which a particularly large amount of gas-rich magma can accumulate.

International aid

The German federal government promised financial aid amounting to ten million DM , half of which was made available to the Chilean government and half to associations and cultural institutions of the German minority , and at the request of the Chilean government sent a commission of experts to the earthquake area.

Financial support also came from Argentina , Sweden and especially the United States .

Long term consequences

Landscape changes

To the north of a line at 38 ° 30 ′ south latitude on the coast of Lebu , there was a spontaneous geological uplift of up to 1.8 meters. In the areas south of it to the island of Chiloé , however, the land subsided by up to 1.5 meters, which led to a permanent change in the coastline and a land loss of 40,000 hectares. On the other hand , Isla Guafo , located southwest of Chiloé in the Pacific, has been lifted by three meters. All nautical charts of the affected area became obsolete.

At times, large parts of the Little South coast sank by up to four meters. Sea water then penetrated many kilometers into river valleys. In the area of Valdivia alone, 15,000 hectares of agricultural land were permanently lost. The wetlands created there are now under nature protection as the Santuario de la naturaleza Carlos Anwandter and are, among other things, a habitat for a large population of black-necked swans . About half of the area of Isla Teja has been flooded by the rivers surrounding it since the earthquake. Current sedimentological studies silt up the flooded land slowly, and the Río Cruces could be back to its original about a hundred years after the quake bed move.

The earthquake triggered numerous landslides , especially in the Andes . There, wooded mountain slopes in particular slid down along the Liquiñe Ofqui fault zone . Due to the low population density, these landslides hardly caused any damage, but the original vegetation of the Valdivian rainforest in the affected areas has not recovered to this day, mostly Coihue southern beeches - monocultures predominate.

Economic and Political Consequences

The earthquake weakened the economic and political importance of Valdivia. The port of Valdivia lost its importance as almost all industrial plants in the city, including the oldest steel mill and the only brewery in the country, had been destroyed. Capital was subsequently withdrawn from the city. The economic influence of the German-Chilean community, whose members had largely owned the companies, declined after the quake.

With the creation of the Chilean regions in 1974, the city and province of Valdivia were added to the Región de los Lagos with the capital Puerto Montt. It was not until the Región de los Ríos was founded in 2007 that Valdivia became the capital of a first-order administrative unit again.

The 1962 World Cup, which took place in Chile two years after the earthquake, had to be limited to venues in the north and center of the country, as the stadiums and infrastructure in the originally planned venues Concepción and Talca had not yet been adequately repaired. A withdrawal from the world championship was also discussed after the quake.

After the devastating series of earthquakes, the Oficina Nacional de Emergencia del Ministerio del Interior (ONEMI) was established in Chile as the national authority for natural disasters , and disaster plans and tsunami warning systems were introduced. Earthquake drills are held regularly in authorities and companies, and the Chilean earthquake safety regulations for buildings are now among the strictest in the world. The comparatively low number of victims after the severe earthquake in Concepción on February 27, 2010 (M w 8.8) suggests that these protective measures have paid off.

Significance for geophysics

This quake was of particular importance for geophysicists , because it was the first time that natural elastic vibrations of the earth were observed with the help of gravimeters , extensometers and long-period seismographs . The earth was struck like a bell by the breaking process in the earth's interior and swung measurably for another week. The event, together with the Good Friday earthquake of 1964 , therefore marks the beginning of a new research direction in seismology , terrestrial spectroscopy .

The free oscillation of the earth, which Hugo Benioff had already observed, was confirmed by several seismologists after the earthquake of 1960, which supported the thesis of the solid core of the earth .

There are also records of earthquakes of similar magnitude in this area from 1575 , 1737 and 1837. The frequency of these extreme events initially threatened to call into question the current theories of plate tectonics , since according to calculations based on the movements of the affected continental plates , earthquakes of the magnitude measured in 1960 should only occur about every 400 years. However, detailed investigations showed that the earthquakes of 1737 and 1837 did not have the strength of the other two earthquakes of 1575 and 1960, but were much weaker.

The Stuttgart geophysicist Wilhelm Hiller saw in the earthquake a confirmation of his now outdated theory of earthquake coupling , according to which earthquakes occur in series and are therefore theoretically predictable .

Reception in popular culture

The Chilean writer Isabel Allende took the earthquake into the plot of her debut novel The Haunted House .

An episode of the 1969 US television series Hawaii Five-Zero relates to the tsunami that devastated Hilo.

See also

literature

Geophysical literature

- Henning Illies : Rim Pacific tectonics and volcanism in southern Chile. In: Geologische Rundschau. No. 57/1, 1967, pp. 81-101.

- Hiroo Kanamori , John J. Cipar: Focal process of the great Chilean earthquake May 22, 1960 ( Memento from February 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 662 kB). In: Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 9 (1974), pp. 128-136.

- Dietrich Lange: The South Chilean subduction zone between 41 ° and 43.5 ° S: seismicity, structure and state of stress. Dissertation at the Institute for Geosciences at the University of Potsdam, 2008 ( PDF; 8.5 MB ; English)

- Francisco Lorenzo-Martin, Frank Roth, Rongjiang Wang: Inversion for rheological parameters from post-seismic surface deformation associated with the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, Chile. In: Geophysical Journal International. No. 164/1, 2006. pp. 75–87 ( PDF; 1.0 MB ; English)

- George Plafker , JC Savage: Mechanism of the Chilean Earthquakes of May 21 and 22, 1960. In: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. No. 81/4, April 1970, pp. 1001-1030 (English).

Geographical literature

-

Wolfgang Weischet : The geographical effects of the earthquake of May 22nd, 1960 in the small south of Chile. In: Geography. No. 14, 1960, pp. 273-288.

- Prerequisite, process and consequences of thixotropic mass displacement into the valley of the Río San Pedro (Prov. Valdivia, Chile). In: Communications of the Geographical Society Munich. Vol. 45, Munich 1960, pp. 39-50.

- Contribución al estudio de las transformaciones geográficas en la parte septentrional del sur de Chile por efecto del sismo del 22 de mayo de 1960 . Universidad de Chile, Instituto de Geología Publ. 15, Santiago de Chile 1960 (Spanish).

- A landscape changes its face: the natural disaster in Chile. I and II. In: A look around in science and technology. No. 62, 1962, pp. 33-36 and pp. 78-81.

Other literature

- Servicio Hidrográfico y Oceanográfico de la Armada de Chile: Cómo sobrevivir a un maremoto. 11 lecciones del tsunami ocurrido en el sur de Chile el 22 de mayo de 1960. Valparaíso 2000 ( online as PDF ( Memento of February 5, 2004 in the Internet Archive ); Spanish).

- Steven Benedetti: El terremoto más grande de la historia, 9.5 judges. Valdivia-Chile, 22 de mayo 1960 . Origo Ediciones, Santiago de Chile 2011, ISBN 978-956-316-073-4 .

Web links

- Conmemoración 50 años Terremoto Valdivia Mayo 1960/2010 (Spanish)

- Memoria Chilena: Valdivia (Spanish)

- National Geophysical Data Center: Earthquake data and images

- United States Geological Survey : The Largest Earthquake in the World (English)

- Press reports

- Earthquake: cracks in the Pacific . In: Der Spiegel . No. 24 , 1960, pp. 56-58 ( online ).

- Time : Chile: Asking for Calm (July 4, 1960)

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung : The tension build-up for extreme earthquakes. Reconstruction of the prehistory of the 1960 earthquake in Chile. (Simone Ulmer, October 9, 2005)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Jean Pierre Rothe: The seismicity of the earth, 1953-1965 . UNESCO , Paris 1969. ( Summary on the United States Geological Survey page )

- ↑ a b c d e National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration : Significant Earthquake Database

- ^ Munich Reinsurance Company : World map of natural hazards. Munich 1978.

- ↑ a b c d e The Largest Earthquake in the World. (No longer available online.) In: earthquake.usgs.gov. United States Geological Survey , archived from the original on March 26, 2014 ; accessed on December 25, 2018 .

- ↑ Werner Zeil: Geology of Chile . Bornträger, 1964. p. 142.

- ↑ Eric Kendrick et al .: “The Nazca-South America Euler vector and its rate of change”. In: Journal of South American Earth Sciences , June 2003, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 125-131.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration : Data on significant earthquakes in Chile between 1950 and 2010

- ↑ a b Der Spiegel 24/1960: Earthquake: Jumps in the Pacific (June 8, 1960)

- ↑ Wolfgang Weischet: "The geographical effects of the earthquake of May 22nd, 1960 in the small south of Chile." In: Gekunde 14. 1960. S. 275.

- ↑ Henning Illies: "Rim Pacific Tectonics and Volcanism in Southern Chile". In: Geologische Rundschau 57/1, Springer, Berlin 1967. pp. 81–101.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey : Earthquake Glossary: rupture velocity , rupture front

- ↑ Hiroo Kanamori, John J. Cipar: Focal process of the great Chilean earthquake May 22, 1960 ( Memento from February 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 662 kB). In: Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors , 9 (1974). Pp. 128-136.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey : Largest Earthquakes in the World Since 1900

- ↑ United States Geological Survey: Table-top earthquakes

- ^ Cinna Lomnitz: "Casualties and behavior of populations during earthquakes". In: Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America . August 1970, v. 60; no. 4. pp. 1309-1313.

- ↑ Universidad Austral de Chile : Map of the earthquake hazard in Valdivia (PDF; 2.7 MB)

- ^ Wolfgang Weischet, Pierre Saint-Amand: “The distribution of the damage caused by the earthquake in Valdivia in relation to the form of the terrain”. In: Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America . December 1963; v. 53; no. 6. pp. 1259-1262.

- ^ Ernest Dobrovolny, Richard Lemke: Engineering Geology and the Chilean Earthquakes of 1960. In: Synopsis of Geologic and Hydrologic Results - Geologic Survey Research 1961. US Government Printing Office, Washington 1961. pp. C-357.

- ↑ Wolfgang Weischet: “Further Observations of Geologic and Geomorphic Changes Resulting from the Catastrophic Earthquake of May 1960, in Chile”. In: Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America . December 1963; v. 53; no. 6; Pp. 1237-1257. Here: p. 1238.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: May 22, 1960 South Central Chile Tsunami Amplitudes ( Memento from April 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Wolfgang Dachroth: "Fernwellen", in: Handbuch der Baugeologie und Geotechnik . Springer, 2002. ISBN 3-540-41353-7 . P. 207.

- ↑ Luis Hernandez Parker: “La Epopeya del Riñihue”, in: Ercilla No. 1308, June 15, 1960, Sociedad Editora Ercilla Limitada, Santiago de Chile, pp. 16-17 (Spanish) (online as pdf; 580 kB) .

- ^ LE Lara, JA Naranjo, H. Moreno: “Rhyodacitic fissure eruption in Southern Andes (Cordón Caulle; 40.5 ° S) after the 1960 (Mw: 9.5) Chilean earthquake: a structural interpretation”. In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research Vol. 138, November 15, 2004, pp. 127-138.

- ↑ NGDC data on volcanic eruption

- ^ Thomas Walter, Frank Amelung: “Volcanic eruptions following M≥9 megathrust earthquakes: Implications for the Sumatra-Andaman volcanoes”. In: Geology , June 2007, vol. 35; No. 6; Pp. 539-542.

- ^ Federal Archives : Minutes of the 109th Cabinet meeting on June 10, 1960, Item A and Minutes of the 110th Cabinet meeting on June 15, 1960, Item C

- ↑ Time : Chile: Asking for Calm (July 4, 1960)

- ^ Charles Wright, Arnoldo Mella: “Modifications to the soil pattern of South-Central Chile resulting from seismic and associated phenomenona during the period May to August 1960”. In: Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America , December 1963, v. 53, no. 6, pp. 1367-1402.

- ^ EG Reinhardt, RB Nairn, G. Lopez: “Recovery estimates for the Río Cruces after the May 1960 Chilean earthquake”. In: Marine Geology , February 2010, v. 269, no. 1-2, pp. 18-33.

- ^ Thomas Veblen, David Ashton: "Catastrophic influences on the vegetation of the Valdivian Andes, Chile". In: Plant Ecology , March 1978, v. 36, no. 3, pp. 149-167.

- ^ Herbert Wilhelmy: The cities of South America: The urban centers and their regions , Volume 2, Bornträger, 1985. ISBN 3-443-37002-0 . P. 170ff.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Huba: World football history: pictures, data, facts from 1846 to today. Copress, Munich 2007. ISBN 3-7679-0958-8 . P. 181f.

- ↑ the ONEMI Official Website

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel : Crouch and pray. The earthquake protection in Chile has apparently worked. (Alexander Kekulé, March 3, 2010)

- ^ Walter Zürn , Rudolf Widmer-Schnidrig: Global natural oscillations of the earth (online as PDF; 1.8 MB) , 2002. p. 1.

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Schlote: Chronology of the natural sciences: the path of mathematics and natural sciences from the beginning into the 21st century. Harri Deutsch Verlag, 2002. ISBN 3-8171-1610-1 . P. 803.

- ↑ Axel Bojanowski : Geologists predict earthquakes and tsunamis . Spiegel Online Wissenschaft, September 15, 2005.