Onagawa (Miyagi)

| Onagawa-chō 女 川 町 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Geographical location in Japan | ||

| Region : | Tōhoku | |

| Prefecture : | Miyagi | |

| Coordinates : | 38 ° 27 ' N , 141 ° 27' E | |

| Basic data | ||

| Surface: | 65.79 km² | |

| Residents : | 5822 (October 1, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 88 inhabitants per km² | |

| Community key : | 04581-1 | |

| Symbols | ||

| Flag / coat of arms: | ||

| Tree : | Crescent fir | |

| Flower : | Cherry Blossom | |

| Fish : | Real bonito | |

| Bird : | Japanese gull | |

| town hall | ||

| Address : |

Onagawa Town Hall 136 Aza Onagawa, Onagawahama Onagawa- chō , Oshika-gun Miyagi 986-2292 |

|

| Website URL: | www.town.onagawa.miyagi.jp | |

| Location Onagawas in Miyagi Prefecture | ||

Onagawa ( Jap. 女川町 , - chō ) is a small town in the district of Oshika the Japanese prefecture of Miyagi .

The city is known for the Onagawa nuclear power plant , some of which is also located in the neighboring Ishinomaki .

geography

Onagawa is located at the northern end of the Oshika Peninsula eastwards along the Sanriku-Ria coast on Onagawa Bay ( 女 川 湾 , -wan ).

In the heart of Onagawa Bay is the port of Onagawa, while the rest of the coastline is home to numerous small fishing villages. The bay opens to the east to the Pacific coast, has a 2.5 km wide bay entrance and a total area of 12.1 km².

Upstream are the two inhabited islands Enoshima ( 江 島 ; 0.36 km²) and Izushima ( 出 島 ; 2.68 km²). There are other uninhabited islands near Enoshima. The entire coast is part of the Minamisanriku Kinkazan Quasi National Park . The inhabited areas are limited to smaller stretches of coast and the valleys of the Kitakami mountainous area , so that most of the municipality is forested. East of the city is the 7.2 km² Mangokuura Lake ( 万 石浦 ). The eponymous Onagawa ("women's river") flows through the city.

With the exception of the coast, Onagawa is surrounded by the city of Ishinomaki, which was created in 2005 from the union of the surrounding communities. Since then, Onagawa has also been the only parish in Oshika County.

The multitude of V-shaped bays on the Sanriku Coast makes it particularly prone to tsunamis by causing the tsunami energy to converge and amplify. Onagawa Bay is a typical example of a V-shaped bay that is wide and deep at the mouth of the bay, but narrower and shallower at the end of the bay, and can possibly increase the wave height of tsunamis, as in Tōhoku -Earthquake 2011.

history

Onagawa was appointed to the village parish ( mura ) on April 1, 1889 . On April 1, 1926, it was upgraded to a small town (chō) .

The town of Onagawa, which is surrounded by mountains and sea, was the main industry of fishing , and many fishermen settled in the town. When the Japanese fishing industry began to shrink in the 1970s, the city made the decision to offer itself as a location for a nuclear power plant . Employees in the construction and utility industries joined the city as residents. The city used the subsidies for housing the nuclear power plant as well as the tax revenues from companies connected with the nuclear power plant to set up a self-sustaining cycle: it built sports and tourist facilities and attracted foreign visitors, who in turn spent their money in Onagawa. When the neighboring city of Ishinomaki merged with six surrounding cities in 2005 and became the second largest city in Miyagi Prefecture, the city of Onagawa decided to remain independent and refused to join the city of Ishonomaki. As a result of this decision, Onagawa remained like an enclave in the middle of Ishinomaki city.

Onagawa - like many other rural Japanese cities - had to contend with problems such as the decline and rapid aging of the population . For further education, young people attended high schools and then college in the nearby city of Ishinomaki, but never returned to the city of Onagawa. The population of Onagawa city halved from 20,000 in 1965 and 16,000 in 1980 to 10,000 in 2010 and 2011. The proportion of the elderly (over 65 years old) was around a third. The tsunami catastrophe triggered by the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011 further exacerbated this pronounced population decline. By 2019, the population had dropped to around 6,500, making Onagawa one of the communities in Japan with the steepest population decline.

Earthquake and tsunami disasters

| Disaster event | Completely destroyed houses | Death toll | source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meiji 1896 (earthquake and tsunami) | 10 | 1 | |

| Shōwa 1933 (earthquake and tsunami) | 56 | 1 | |

| Chile 1960 (earthquake and tsunami) | 192 | 0 | |

| Tōhoku 2011 (earthquake and tsunami) | 2939 | 850 | |

| Note: The death toll for the 2011 Tōhoku disaster is calculated from the total number of dead and missing in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016, minus the figures for catastrophe-related deaths determined by the Reconstruction Agency (RA). | |||

Historical tsunami experiences and countermeasures

Before the Tōhoku tsunami of 2011, the city of Onagawa had two breakwaters that were built after the Chile tsunami of 1960 and were located about 1.5 km east of the port at the entrance to the bay, each 300 m in length and in a maximum depth of 28 m. A gap of 150 m had been left between the two breakwaters.

Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami 2011

Extent of flooding and damage

The Tōhoku earthquake of March 11, 2011 triggered a tsunami that hit Onagawa about 34 minutes later, at 3:20 p.m. The tsunami reached a flood height of 14.8 m in Onagawa. According to other information, the maximum flood height in the city exceeded 16 m, favored by the east current of the tsunami with simultaneous east exposure of Onagawa Bay. The tsunami flooded three square kilometers and 48 percent of the area in the residential areas of Onagawa. A large part of the urban area was destroyed, including 12 of the 25 tsunami emergency shelters (all in locations over 6 m high). The number of completely destroyed residential buildings is put at 2924. Of the 4,607 tsunami-exposed buildings in the flooded area of Onagawa City, 3,459 were destroyed and washed away, representing a rate of 75.1%, the second highest rate in Miyagi Prefecture after Minamisanriku City .

The two breakwaters, which were built at the entrance to Onagawa Bay to protect the port of Onagawa from high wind waves, were completely destroyed by the tsunami, with the exception of a few caissons located close to land on each side of the bay . Although the breakwater was not designed to withstand tsunamis, it was not expected to fail completely.

In the northeastern part of Onagawa Bay, the village of Takenoura, which is mainly a small fishing village, the entire area was flooded by the tsunami, despite the breakwater at the entrance to the bay and one that rises 1.75 m above ground level Seawalls in front of the village. In the village, on the landward side of the seawall, flood heights of 11.05 m and 8.73 m and on the seaward side of 11.91 m were measured. The breakwater suffered partial damage, with the upper part of the breakwater destroyed in many places.

At the time of the earthquake, a two-car train on the Ishinomaki Line was ready to depart from JR East Onagawa Station . The tsunami tore this train along with him, just as another train, which for some hot springs - equipment was used. Of the two trains from the two-day formation, one drifted about 200 m away and was completely destroyed, while the other drifted 100 m further inland and came to a cemetery on a hill. In addition, the station building and the railway line were badly damaged.

The tsunami tracks found along the coastline of Onagawa Bay corresponded to a tsunami height of over 10 m. At the innermost part of Onagawa Bay, the tsunami advanced over a kilometer inland, following the narrow valleys that cut into the coastal hills that surround the city of Onagawa. The tsunami wave rose to almost 18 m and towered over almost all buildings in the area with the exception of those on a centrally located hillside. Although the city of Onagawa also had a higher part that was less affected by the tsunami, the main area of the city was located around the port. Around the port of Onagawa, many buildings, including the reinforced concrete structures, were partially or completely destroyed. In the urban developed area, all wooden buildings collapsed up to 400 m inland, and most steel frame buildings suffered moderate to severe damage and collapsed. Many reinforced concrete buildings suffered moderate damage, and some were badly damaged by tipping over.

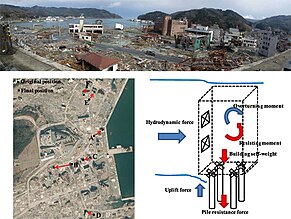

- Overturning and drifting of multi-storey reinforced concrete or steel frame buildings

Below left: Map with the original (dots) and the position of the 6 buildings (A – F), which was moved by the tsunami (crosses).

Below right: Free body image of the overturn

(Photos: March 29 and July 9, 2011)

The city of Onagawa experienced some of the most surprising findings of building damage during the Tōhoku disaster. At least eight reinforced concrete or steel structures were found in the cities of Onagawa and Miyako that had been overturned and torn away by the tsunami. In addition to Onagawa and Miyako, a similar overturning of a reinforced concrete building also occurred in Ōtsuchi in at least one case.

Six of these cases occurred in Onagawa alone. Five reinforced concrete shear wall buildings and one steel frame building, all two to three storeys high, were overturned and moved from their original positions during the tsunami. This type of construction failure had not been observed for reinforced concrete shear wall buildings or steel frame buildings exposed to tsunamis until then. Over half a dozen buildings were overturned and moved, but structurally they were still complete from the foundation to the roof. These buildings had been swept up and carried away by hydrostatic buoyancy , or they had been overturned by hydrodynamic forces from the inflow or return of the tsunami, or a combination of both. These buildings may have had a larger width-to-height ratio than other buildings nearby, and they all had a small footprint. Some had pile foundations , others had foundation plates . According to witnesses, the first incoming tsunami wave knocked these buildings down.

- One of these buildings (building "B" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017, "C" in the sense of Fraser & al. 2013), a three-story reinforced concrete shear wall building with an additional fourth floor , which was used as a shelter, was moved 70 m from its original place until it reached the steeply rising and fortified hill. on which the hospital lies, came to a standstill.

- A two-story reinforced concrete cold store (building "D" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017, "E" in the sense of Fraser & al. 2013), which with the exception of doors and a few windows on the second floor Consisting of a closed concrete shell, was lifted by hydrostatic buoyancy from its pile foundation, which had no tensile strength , and carried over a low wall before it was lowered about 15 m inland from its original position on the side.

Other overturned concrete and steel buildings were built so openly that the hydrostatic buoyancy could be relieved, but were overturned by hydrodynamic forces in the incoming or returning tsunami current.

- A four-storey office building (building "C" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017, "D" in the sense of Fraser & al. 2013) with a moment-bearing steel frame had numerous window openings and lost many of its lightweight precast concrete parts, but despite the open structure, its spun concrete hollow piles were sheared off or pulled out of the ground, and the building was overturned and moved about 15 m.

- A two-story reinforced concrete building (Building "E" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017, "A" in the sense of Fraser & al. 2013), the lower story of which was used as a police station, was overturned by the tsunami and washed into its final position by the returning tsunami. According to the damage findings, it was possibly knocked over by the impact of rubble.

Objections from the builders and residents were directed against the city's preservation of all six buildings as memorials. The city of Onagawa decided that of the three reinforced concrete buildings that had collapsed in Onagawa, only the overturned building of the Onagawa Police Box (女 川 交 番) (Building "E" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017) in Onagawahama as a disaster ruin to obtain. The decision to maintain this building was made based on criteria such as maintenance work schedule, building stability and maintenance costs. The other two buildings in Onagawahama, which were initially kept as a research object, were, however, very close to the quay, were considered to be an obstacle to the coastal defense work and were finally released for demolition, whereupon their demolition began in 2014: The four- story Onagawa Supplement with one built in 1967 Pharmacy on the first floor where the tsunami had washed a vehicle. And the four-storey (16.8 m high) steel frame construction with reinforced concrete Eshima Kyosai-Kaikan (building "C" in the sense of Latcharote & al. 2017), which had served as a residential building and was swept away by the tsunami.

Despite the extreme hydrodynamic forces in this area, many buildings survived the tsunami due to the dense urban development that provided a certain level of protection. A 4-storey complex of 2 buildings right on the harbor sustained considerable damage to the glazing, limited damage to the masonry and the loss of an elevated pedestrian crossing that connected the two buildings. With the help of a video that a surviving resident made during the disaster from the roof of this reinforced concrete complex in the port of Onagawa and which was partially uploaded to the website of the Japanese magazine Yomiuri Shimbun , the current speed of the ascending tsunami in the city of Onagawa at the time the tsunami began to wash away houses, estimated at 6.3 m / s, and the flow velocity for the returning tsunami at 7.5 m / s, each with a flow depth of approximately 5 meters. These conditions are considered sufficient for the overturning of the reinforced concrete buildings. Smaller buildings in the lee of this building complex directly at the harbor or other massive structures were protected from the ascending tsunami flow and remained standing, although they suffered severe damage to non-load-bearing elements during the tsunami reflux.

Victim

The fire and disaster control authorities reported 473 dead and 620 missing in their damage report of May 19. The number of deaths increased to 615 in the later damage record, while 258 people were still missing.

The proportion of victims in Onagawa was about 8.7 percent of the population, which had been given as about 10,000 before the disaster. If all the dead and missing persons registered in the 157th FDMA damage report of March 7, 2018 are taken into account, the result is a victim rate due to the disaster of 8.7%. If one takes into account the victims registered in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016 (613 dead and 259 missing) minus the catastrophe-related deaths reported by the Reconstruction Agency (RA), which results in a number of 850 dead and missing, see above the victim rate is 8.46%. With the same data basis, but based solely on the floodplain area of the tsunami in Onagawa, which covered an area of 3 km 2 , the casualty rate was 10.56%, according to other calculations, 11.9%. The surprisingly high casualty rate can be seen as an indication that it was difficult to survive in the city of Onagawa in the event of a nearly 20 m high tsunami.

In the entire greater Ishinomaki area, which also includes Onagawa along with Ishinomaki and its neighboring city Higashimatsushima , almost 220,000 people were living at the time of the disaster, of whom 5,300 were killed and around 700 were missing.

| Area in Onagawa | Fatalities | Residents | Tsunami | Distance to the next evacuation site [m] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate [%] | number | Max. Flooding height [m] | Arrival time [min.] | |||

| Onagawahama | 9.84 | 175 | 1,778 | 4.41 | 39 | 757 |

| Washinokamihama | 6.39 | 112 | 1,753 | 19.07 | 39 | 485 |

| Onmaehama | 8.72 | 41 | 467 | 13.03 | 40 | 525 |

| Takeura | 6.59 | 12 | 182 | 11.91 | 40 | 452 |

| Oura | 5.19 | 12 | 231 | 11.31 | 40 | 377 |

| Konorihama | 4.84 | 9 | 186 | 16.56 | 39 | 266 |

| Takashirohama | 1.35 | 1 | 74 | 15.93 | 39 | 131 |

| Yokoura | 9.43 | 10 | 106 | 14.90 | 42 | 626 |

| Nonohama | 3.95 | 3 | 76 | 17.19 | 40 | 326 |

| Igohama | 6.00 | 6th | 100 | 15.59 | 42 | 526 |

| Tsukahama | 3.40 | 10 | 294 | 12.59 | 42 | 348 |

| Source: Total population according to Statistics Bureau (統計局) and Director-General for Policy Planning (政策 統 括 官), 2010 census; Fatalities according to fire and disaster management agency (消防 庁 = Fire and Disaster Management Agency, FDMA); Maximum flood height and arrival time of the tsunami according to The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami Joint Survey Group ; Distance to the nearest evacuation site from the place of residence according to the evacuation site data from the Cabinet Secretariat Civil Protection Portal Site ( http://www.kokuminhogo.go.jp/en/pc-index_e.html ) of the Cabinet Secretariat (内閣 官 房) and the aerial photographs and maps from Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI) from the Tsunami Damage Mapping Team, Association of Japanese Geographers. | ||||||

evacuation

The fact that the high mortality rate in the flood zone of the city of Onagawa was higher than that of the city of Minamisanriku , the flooded area of which was similarly populated and had a similar flood level, suggests significant differences in evacuation behavior between these two cities.

In the main area of the city were the City Hall, a hospital and Onagawa Station , all of which suffered severe damage. At the town hall, the tsunami rose to the third floor, which corresponds to a flood height of 13.52 m.

The ground floor and up to a height of 2 m also the first floor of the city hospital, which is located 145 m inland from the port and designated as an evacuation site, were flooded, although it was located on a hill above the port, 15 to 16 m above sea level . This results in a flooding height of 17.39 m. The flooding was enough to allow vehicles 16 m above the ground to float in the hospital parking lot.

28 people were rescued in a boiler room of a five-story reinforced concrete building in Onagawa City that was completely flooded by the tsunami.

traffic

The place is connected to the rail network with JR East Ishinomaki Line , which starts from Kogata in Misato and ends in Onagawa. The city has two train stations: Urashuku and Onagawa.

The most important trunk road is the national road 398 to Ishinomaki or Yurihonjō .

Ferries go from the port via Izushima to Enoshima and to the island of Kinkasan, which is administered by Ishinomaki .

education

Onagawa has three elementary schools, two high schools, and one prefectural high school.

Web links

- 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図 , 国土 地理 院 ( Kokudo Chiriin , Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, formerly: Geographical Survey Institute = GSI), www.gsi.go.jp: 地理 院 ホ ー ム> 防災 関 連> 平 成 23 年 (2011年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 に 関 す る 情報 提供> 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図:

- The GSI published here two maps with Onagawa ( 浸水範囲概況図10 , 浸水範囲概況図11 ) on which the 2011 flooded the Tōhoku tsunami areas are drawn on the basis of reports of aerial photographs and satellite imagery, as far as was possible.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Takahito Mikami, Tomoya Shibayama, Miguel Esteban, Ryo Matsumaru: Field survey of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures . In: Coastal Engineering Journal . tape 54 , no. 1 , March 29, 2012, p. 1250011-1-1250011-26 , doi : 10.1142 / S0578563412500118 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Shunichi Koshimura, Satomi Hayashi, Hideomi Gokon: The impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami disaster and implications to the reconstruction . In: Soils and Foundations . tape 54 , no. 4 , August 2014, p. 560-572 , doi : 10.1016 / j.sandf.2014.06.002 . (Published online July 22, 2014).

- ↑ a b c d 東 日本 大 震災 記録 集 ( Memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency) des 総 務 省 (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications), March 2013, here in Chapter 2 (第 2 章 地震 ・ 津 波 の 概要) the subsection 2.2 (2.2 津 波 の 概要 (1)) ( PDF ( Memento of March 28, 2018 on WebCite )), p. 40, Figure 2.2-11 ("V 字型 の典型 的 な 場所 の 例 (女 川 町 ").

- ↑ a b c Mayuka Yamazaki (with the assistance of Fumika Yoshimine and Hiroko Yanagisawa): "Rebuilding the Tsunami-Stricken Onagawa Town", [July 2013?]. ETIC (Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities)> Disaster Recovery Leadership Development Project> Case Studies from Tohoku> Case3 (URL: http://www.etic.or.jp/recoveryleaders/en/wp-content/uploads/Rebuilding-Onagawa. pdf )

- ↑ a b Richard Vize: The town that outlawed sprawl Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. In: The Guardian . 17th April 2019.

- ↑ Mayuka Yamazaki (with the assistance of Fumika Yoshimine and Hiroko Yanagisawa): "Rebuilding the Tsunami-Stricken Onagawa Town", [July 2013?]. ETIC (Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities)> Disaster Recovery Leadership Development Project> Case Studies from Tohoku> Case3 (URL: http://www.etic.or.jp/recoveryleaders/en/wp-content/uploads/Rebuilding-Onagawa. pdf ). With reference to: "Onagawa's Statistics FY 2012", p. 10, "Onagawa's plan on welfare for the elderly - business plan of nursing care", March 2013, p. 10.

- ↑ a b c d e f Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online August 15, 2017). With reference to: Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Forensic investigation of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster: a case study of Rikuzentakata , Disaster Prevention and Management, 26 (3) (2017), pp. 298-313 , doi: 10.1108 / DPM-10-2016-0213 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Stuart Fraser, Alison Raby, Antonios Pomonis, Katsuichiro Goda, Siau Chen Chian, Joshua Macabuag, Mark Offord, Keiko Saito, Peter Sammonds: Tsunami damage to coastal defenses and buildings in the March 11th 2011 Mw9.0 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami . In: Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering . tape 11 , 2013, p. 205-239 , doi : 10.1007 / s10518-012-9348-9 . (Published online March 27, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f Shunichi Koshimura, Nobuo Shuto: Response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster . In: Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society A Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences . tape 373 , no. 2053 , 2015, p. 20140373 , doi : 10.1098 / rsta.2014.0373 (published online on September 21, 2015).

- ↑ a b Nobuo Mimura, Kazuya Yasuhara, Seiki Kawagoe, Hiromune Yokoki, So Kazama: Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami - A quick report . In: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change . tape 16 , no. 7 , 2011, p. 803-818 , doi : 10.1007 / s11027-011-9304-z . (Published online May 21, 2011).

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . (No longer available online.) In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, March 25, 2011, archived from the original on May 1, 2011 ; Retrieved May 3, 2011 (Japanese).

- ^ Number of dead, missing rises to 1,400. (No longer available online.) In: Daily Yomiuri Online. Yomiuri Shimbun- sha, March 13, 2011, archived from the original on October 24, 2016 ; accessed on March 13, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Tsunami hit more than 100 designated evacuation sites. (No longer available online.) In: The Japan Times Online. April 14, 2011, archived from the original on September 8, 2011 ; accessed on May 3, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 157 報) ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 18, 2018 on WebCite )) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 157th report, March 7, 2018.

- ↑ a b c Soichiro Shimamura, Fumihiko Imamura, Ikuo Abe: Damage to the Railway System along the Coast Due to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami . In: Journal of Natural Disaster Science . tape 34 , no. 1 , 2012, p. 105-113 , doi : 10.2328 / jnds.34.105 .

- ↑ a b c d e Ian Nicol Robertson, Gary Chock: The Tohoku, Japan, Tsunami of March 11, 2011: Effects on Structures . In: EERI Special Earthquake Report . September 2011, p. 1-14 . , Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI).

- ↑ P. Latcharote, A. Suppasri, A. Yamashita, B. Adriano, S. Koshimura, Y. Kai, F. Imamura: Possible Failure Mechanism of Buildings Overturned during the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami in the Town of Onagawa . In: Front. Built Environ. tape 3:16 , March 16, 2017, p. 1-18 , doi : 10.3389 / fbuil.2017.00016 . , here: p. 3, Fig. 1. "Six overturned buildings in the town of Onagawa and free-body-diagram of building overturning", License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1006, Figure 18. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ P. Latcharote, A. Suppasri, A. Yamashita, B. Adriano, S. Koshimura, Y. Kai, F. Imamura: Possible Failure Mechanism of Buildings Overturned during the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami in the Town of Onagawa . In: Front. Built Environ. tape 3:16 , March 16, 2017, p. 1-18 , doi : 10.3389 / fbuil.2017.00016 . , here: p. 4f, Fig. 2 (AE) "The characteristics of five overturned buildings in the town of Onagawa", License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1007, Figure 20. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1007, Figure 19. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ a b c d e Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online July 7, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e f P. Latcharote, A. Suppasri, A. Yamashita, B. Adriano, S. Koshimura, Y. Kai, F. Imamura: Possible Failure Mechanism of Buildings Overturned during the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami in the Town of Onagawa . In: Front. Built Environ. tape 3:16 , March 16, 2017, p. 1-18 , doi : 10.3389 / fbuil.2017.00016 .

- ↑ a b Tetsuo Tobita, Susumu Iai: Over-turning of a building with pile foundation - combined effect of liquefaction and tsunami . In: 6th International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering (ICEGE15) - November 1-4, 2015 - Christchurch, New Zealand . November 1, 2015, p. 1-9 . (This is not a peer-reviewed publication, but a lecture at the conference cited).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri: The 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Background, Characteristics, Damage and Reconstruction . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 27-34 .

- ↑ a b c Isao Hayashi: Materializing Memories of Disasters: Individual Experiences in Conflict Concerning Disaster Remains in the Affected Regions of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology [ 国立 民族 学 博物館 研究 報告 ] . tape 41 , no. 4 , March 30, 2017, p. 337-391 , doi : 10.15021 / 00008472 .

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 124 報) ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 124th report, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . (No longer available online.) In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, May 20, 2011, archived from the original on June 19, 2011 ; Retrieved June 19, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

- ↑ a b 東 日本 大 震災 記録 集 ( Memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), March 2013, here in Chapter 3 (第 3 章 災害 の 概要) the subsection 3.1 / 3.2 (3.1 被害 の 概要 /3.2 人 的 被害 の 状況) ( PDF ( Memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite )).

- ↑ a b 平 成 22 年 国 勢 調査 - 人口 等 基本 集 計 結果 - (岩手 県 , 宮城 県 及 び 福島 県) ( Memento from March 24, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF, Japanese), stat.go.jp (Statistics Japan - Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and communication), 2010 Census, Summary of Results for Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, URL: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/index.html .

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online on August 15, 2017), here p. 22, table 2.

- ↑ a b 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 153 報) ( Memento of March 10, 2016 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 153. Report, March 8, 2016.

- ↑ a b Kimiaki Sato, Michio Kobayashi, Satoru Ishibashi, Shinsaku Ueda, Satoshi Suzuki: Chest injuries and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Respiratory Investigation . tape 51 , no. 1 , March 2013, p. 24–27 , doi : 10.1016 / j.resinv.2012.11.002 . (Published online on). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

- ↑ Nam Yi Yun, Masanori Hamada: Evacuation Behavior and Fatality Rate during the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Earthquake Spectra . tape 31 , no. 3 , August 2015, p. 1237-1265 , doi : 10.1193 / 082013EQS234M . , here table 2.