Ishinomaki

| Ishinomaki-shi 石 巻 市 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Geographical location in Japan | ||

|

|

||

| Region : | Tōhoku | |

| Prefecture : | Miyagi | |

| Coordinates : | 38 ° 26 ' N , 141 ° 18' E | |

| Basic data | ||

| Surface: | 555.78 km² | |

| Residents : | 141,293 (October 1, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 254 inhabitants per km² | |

| Community key : | 04202-1 | |

| Symbols | ||

| Flag / coat of arms: | ||

| Tree : | Japanese black pine | |

| Flower : | azalea | |

| town hall | ||

| Address : |

Ishinomaki City Hall 1 - 1 - 1 , Hiyorigaoka Ishinomaki -shi Miyagi 986-8501 |

|

| Website URL: | http://www.city.ishinomaki.lg.jp/ | |

| Location Ishinomakis in Miyagi Prefecture | ||

Ishinomaki ( Japanese 石 巻 市 , -shi ) is a city in Miyagi Prefecture on Honshū , the main island of Japan .

geography

Ishinomaki is located south of Kesennuma on the Pacific Ocean . The city is also located around 50 km northeast of Sendai , one of the largest metropolises in the Tōhoku region .

The coast in front of the city of Ishinomaki marks the northern end of the Pacific flat coast in the Tōhoku region, which extends south to Minamisōma , but also includes part of the Ria coast as a typical landform for the Sanriku coast that adjoins to the north .

The coastal zone at Ishinomaki Bay is politically divided between the municipalities of Ishinomaki and Higashimatsushima and combines a variety of land use zones including urban and industrial areas, residential areas and rural areas. In addition to the Matsushima military airport (松 島 基地) in Higashimatsushima, there is a commercial port and a fishing port. The local economy is primarily based on fishing, the fishery products industry and agriculture.

Ishinomaki is the second largest city in Miyagi, only Sendai has a larger population in the prefecture. Ishinomaki has a 12 km long south-facing coastline, which is largely occupied by storage and industrial sites of the fishing port and the commercial port . The densely built, urban developed area extends up to 4.8 km inland. Within the 400 meters closest to the port there is a commercial and industrial area, which is connected further inland with residential areas and small commercial areas.

The geomorphological nature of Ishinomaki Bay makes the area particularly prone to tsunami events, as it is a flat coastline surrounded by the two bays of Ishinomaki and Matsushima, both of which are flat and characterized by a relatively flat (smooth ) Mark the seabed. The area has an extensive hydrographic network consisting of the Kitakami (北上 川, in Ishinomaki), Jo (定 川, between Ishinomaki and Higashimatsushima), and Naruse (鳴 瀬 川, in Higashimatsushima) rivers connected by canals. Hiyoriyama Hill (日 和 山, in Ishinomaki) and the local coastal forests are the only natural barriers to tsunami waves in the tsunami-prone area of Ishinomaki Bay.

Neighboring cities and communities

history

In the early 17th century, the city center of old Ishinomaki at the mouth of the Kyūkitakami River flourished as the main economic and logistical transshipment point for boat freight. In the late 18th to early 19th century, the place prospered as a town with a neighboring fishing ground off the island of Kinkasan (金華 山). In recent years, the city also developed into an industrial city. Smaller towns on the peninsula, such as old Oshika and old Ogatsu, consist primarily of fishing villages that were closely linked to and shaped by the fishing industry and related industries in the region. The word hama (literally: "beach") is found in their names .

The community Ishinomaki was established on April 1, 1889 during the introduction of modern Japanese community service and was a district town ( chō ) in Oshika County . On April 1, 1993, the city was named an independent city ( shi ).

The current community was created in 2005 from the merger of the old Ishinomaki community with six surrounding communities. The present-day form of the city arose, consisting of both a wide plain, on which the urban district emerged, and a peninsula with a Ria coastal profile, i.e. a complex landscape in which the mountains border the sea. While Ishinomaki became the second largest city in Miyagi Prefecture through the merger in 2005 with the six surrounding cities, the neighboring city of Onagawa decided to remain independent and as a result remained like an enclave in the middle of the city of Ishinomaki. The six communities with which the ancient Ishinomaki merged were the cities of Monou , Kanan , Kahoku , Kitakami , Ogatsu , each in Monou County and Oshika in Oshika County. This led to the dissolution of Monou County, while Oshika County consisted only of Onagawa Township.

Earthquake and tsunami disasters

Historical tsunami experiences and countermeasures

In Ogatsucho-Wakehama (雄 勝 町 分 浜) there was a tsunami height of 2 m for the Sanriku tsunamis triggered by the Meiji-Sanriku earthquake in 1896 and the Shōwa-Sanriku earthquake in 1933 and one for the tsunami triggered by the Chile earthquake in 1960 Height of 3 m has been reported.

Before the Tōhoku disaster of 2011, it was estimated that 164 people would be killed in such a disaster in Ishinomaki using computational flood simulations based on an expected Miyagi-ken-oki earthquake of JMA magnitude 8.0. The maximum flood height of a tsunami triggered by such a predicted event was assumed to be 3 m directly at the port and 1 m at a distance of 500 m inland.

Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami 2011

Extent of flooding and damage

"CBD" (for: central business district ) refers to the central business district of the city of Ishinomaki.

black numbers : flooding or run-up heights [m]

blue : floodplains

bar charts : Population (left) and dead (right) ages 0-15 (below), 16-64 (center) and ≥65 (top)

Above: Photo taken on August 8, 2008 (normal water levels).

Bottom: Photo from March 14, 2011 (city still partially flooded)

Scene of the Ōkawa elementary school incident with the Kitakami bridge (center)

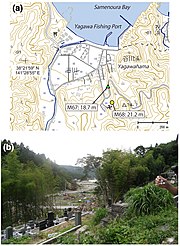

a: Flood height (triangle) and run-up height (circle)

b: View from the survey point at which an run-up height of 21.2 m was measured.

levels (triangles) in Onosaki (M43, M46) and Nagatsura (M44-45, M47-48).

b, c: Tsunami damage and subsidence in Onosaki and Nagatsura

The city was hit on March 11, 2011 by a tsunami triggered by the Tōhoku earthquake , which had a flood height of 15.5 m in Ishinomaki and an area of 73 square kilometers (13 percent of the total city area), including 46 percent of the area in the residential areas, flooded. Although only 13.2 percent of the total urban area was flooded, 76 percent of the houses in the city suffered damage and the city center in particular would be completely flooded. Ishinomaki, from where the tsunami left traces of impact 49 km upstream of the Kitakami, is an example of the places where the tsunami emergence caused significant damage along important rivers in the region in addition to the direct attack from the coast.

Unlike in Rikuzentakata and Natori , for example, almost all of the pines in the regulatory forest in Ishinomaki survived the tsunami. The forests here mitigated the destructive force of the tsunami and captured debris from the floods, such as vehicles, before they could penetrate the city. Possibly the trees were spared because the height of the tsunami in Ishinomaki was lower at around 6 m. The dike, which was later destroyed, could also have helped the trees to protect them.

Investigations at several points over 470 m inland revealed tsunami flood heights of at least 4 m. In the main port facilities in the southwest of the metropolitan area, water heights in the range of 4.5 to 5 meters were found. Warehouses and reinforced concrete buildings suffered some damage but did not collapse.

Ishinomaki was one of the largest cities hit by the tsunami. Around 20,000 residential buildings were completely destroyed and around 13,000 partially destroyed. Almost 17,000 residents were evacuated.

Fishing ports, industrial parks and residential areas along the coast have been completely washed away and destroyed in ruins. The Ishinomaki fishing port was the third largest in the country in terms of total landings at the time of the tsunami. Fishing and seafood processing, the city's main industries, employed thousands of people in hundreds of businesses. Measurements show that the tsunami height in the Ishinomaki fishing port was about 4 times higher than the estimates modeled in advance of the disaster, which had expected a tsunami that would be triggered by a predicted Miyagi-ken-oki earthquake of JMA magnitude 8.0 .

The port of the city of Ishinomaki, one of the largest ports north of Sendai and a center of the rice trade , was almost fully operational again in May 2011.

The rest of the city, however, was largely very badly damaged. The tsunami flooded almost the entire central business district of the city. In addition to the damage to buildings and systems, the earthquake also caused the ground to sink by around 1.4 meters, so that seawater could penetrate the area at high tide. The land subsidence extended over an extensive area. In Ayukawa-hama (鮎 川 浜) on the Oshika peninsula , a subsidence of 1.2 m was registered. Although the waves were not of great amplitude, water penetrated deeply into the urban area and came more than three kilometers inland from the coast, killing many residents who were not evacuated.

Although the majority of the buildings in the flooded area of the city of Ishinomaki remained standing, some areas around the mouth of the Old Kitakami, where there had been considerable subsidence of coseismic subsidence of up to 0.78 m, were almost completely destroyed. Subsequently, at high tide, sunken land was flooded at the river mouth and directly at the port .

Due to the large amount of debris in the water, including the boats, it also damaged some areas above the flood level.

In Ishinomaki-Yagawahama (谷川 浜) the tsunami washed away almost all the houses and covered the agricultural areas with sedimentary deposits such as sand, shell fragments and gravel. Tsunami tracks indicate a flood height of 18.7 m. The maximum incidence height of 21.2 m in Miyagi Prefecture was measured in the cemetery behind the Tofuku-ji Temple (洞 福寺).

In the area around Ishinomaki-Nagazuraura (or: Nagazuraura Bay / 長 面 浦), a brackish lake connected to the Bay of Oppa , the tsunami flooded almost all houses. Japanese black pines and houses were washed away at the mouth of the Kitakama River . Significant subsidence led to the flooding of houses and rice fields. Sand was deposited all over the residential area. In the Onosaki district (Bezirk) east of Nagazuraura, flood heights of 4.2 and 3.9 m were measured. In the Nagatsura (長 面) district to the west of Nagazuraura, the flooding reached heights of 4.1 to 7.1 m. Some residents drowned in the temple where they had been evacuated on the mistaken belief that it was at a safe height.

In Ogatsucho-Wakehama (雄 勝 町 分 浜) the tsunami heights of 2011 exceeded those of the Chile tsunami of 1960 , which in turn was higher than the Sanriku tsunamis of 1896 and 1933 . The 2011 tsunami flooded areas up to a temple 250 m from the coast and washed away almost all houses. Its run-up height was 14 m.

In the Ogatsu and Kitakami districts of Ishinomaki city, around 30,000 old documents were destroyed by the impact of the tsunami, but their image contents were held in more than 70,000 electronic files before the disaster. At the Museum of Culture in Ishinomaki, which was badly damaged by the tsunami, teams of experts carried out fumigation, cleaning, drying or restoration of folklore objects, works of art, handicrafts, excavated human skeleton parts and historical maps, which they then transferred to other museums, universities and private storage facilities in Sendai and Tokyo and kept there.

Victim

Because of the high number of people exposed to the tsunami, Ishinomaki had the most casualties of any community in the Tōhoku region and Japan. The fire and disaster control authority reported in its damage report from May 19, 2964 dead and 2770 missing. The number of deaths increased to 3554 in the later damage record, while 421 people were still missing. This made Ishinomaki the hardest hit community in the 2011 disaster in Japan in terms of absolute casualties.

Measured against the total population of Ishinomaki, which was given as 160,826 in the 2010 census, the casualty rate from the 2011 disaster was 2.5%, if all dead and missing persons registered in the 157th FDMA damage report of March 7, 2018 are taken into account or 2.30% if the victims recorded in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016 (3,547 dead and 428 missing) minus the catastrophe-related deaths reported by the Reconstruction Agency (RA) are taken into account, resulting in a Number of 3,705 dead and missing results. With the same data basis, but based solely on the flood area of the tsunami in Natori, which covered an area of 73 km 2 , the casualty rate was 3.30%, according to other calculations 3.6%. 112,276 people and thus 69% of the total population of the city of Ishinomaki (assuming 162,822 inhabitants in 2010) had their residence in the area flooded by the tsunami on March 11, 2011.

In relation to the population in the flooded areas, this means a relatively low mortality rate for Ishinomaki compared to other places where 70 to 80% of the population in the flooded area also lived (such as in Rikuzentakata , Ōtsuchi , Onagawa and Minamisanriku ).

Members of the Volunteer Fire Brigade (Syobo-dan) died trying to close tsunami flood gates in Ishinomaki city.

In the entire Ishinomaki metropolitan area, which includes Ishinomaki and its neighboring cities Higashimatsushima and Onagawa , almost 220,000 people were living at the time of the disaster, of whom 5,300 were killed and around 700 were missing.

| Ishinomaki area | Fatalities | Residents | Tsunami | Distance to the next evacuation site [m] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate [%] | number | Max. Flooding height [m] | Arrival time [min.] | |||

| Minamihama | 8.28 | 218 | 2,634 | 5.97 | 122 | 686 |

| Harioka | 14.64 | 88 | 601 | 1.10 | 36 | 1,388 |

| Nagaomote | 15.61 | 79 | 506 | 3.88 | 36 | 2,471 |

| Daimon | 8.05 | 77 | 957 | 2.75 | 118 | 821 |

| Kadzumaminato | 9.07 | 66 | 728 | 3.61 | 122 | 1,520 |

| Nakayashiki | 7.56 | 44 | 582 | 2.39 | 60 | 1,758 |

| Kodzumihama | 7.69 | 4th | 52 | 8.79 | 120 | 813 |

| Ise | 5.45 | 21st | 385 | 3.66 | 122 | 2,753 |

| Nakaura | 5.80 | 12 | 207 | 3.80 | 60 | 1,490 |

| Kawaguchi | 6.20 | 37 | 597 | 3.51 | 122 | 894 |

| Yahata | 6.40 | 35 | 547 | 2.01 | 122 | 769 |

| Source: Total population according to Statistics Bureau (統計局) and Director-General for Policy Planning (政策 統 括 官), 2010 census; Fatalities according to fire and disaster management agency (消防 庁 = Fire and Disaster Management Agency, FDMA); Maximum flood height and arrival time of the tsunami according to The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami Joint Survey Group ; Distance to the nearest evacuation site from the place of residence according to the evacuation site data from the Cabinet Secretariat Civil Protection Portal Site ( http://www.kokuminhogo.go.jp/en/pc-index_e.html ) of the Cabinet Secretariat (内閣 官 房) and the aerial photographs and maps from Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI) from the Tsunami Damage Mapping Team, Association of Japanese Geographers. | ||||||

evacuation

In Ishinomaki there was extensive informal, i.e. unplanned, evacuation on March 11, 2011. After the government's vertical evacuation lines were drawn up in 2005, the city of Ishinomaki had agreements with three private companies in the Minato-mnachi district to evacuate three of its buildings, which were occupied by around 500 people on March 11, 2011 . Although all three buildings only had two storeys, they were sufficient for the flood height on March 11, 2011 for evacuation. In addition to these designated evacuation buildings, almost all buildings that were taller than a two-story residential building were used for vertical evacuation on March 11, 2011. In total, around 260 official and unofficial evacuation points were used, providing refuge for around 50,000 people, including in schools, temples, shopping centers and homes. In addition, another 50,000 people were trapped on the upper floors of houses. In light of the experience of this tsunami, a shortage of evacuation buildings has been identified west of the Kitakami.

In some places, it was necessary to move those who had already been evacuated. For example, in the Kadonowaki elementary school with its school building typical of Japan, which was flooded right up to the first floor within an hour after the earthquake and was additionally damaged by fire. The building of the Kadonowaki School then showed considerable external fire damage. The school in Kadonowaki (門 脇) caught fire due to vehicles carried away by the tsunami and their fuel caught on fire. Those evacuated to the school managed to leave the school before the fire broke out and to move further inland to a higher school. After teachers heard of the tsunami warning, they led 275 students (some of whom were already back home) to high-altitude Hiyoriyama Park, where all survived. Overall, all refugees from Kadonowaki primary school were able to get to safety in Hiyoriyama Park. The case of the school is considered a perfect example for future generations, which interacts with the nearby memorial park. The school building with its permanent tsunami-induced fire marks became a valuable disaster ruin, which is to be used as an educational resource to strengthen awareness of disaster control and disaster risk management. On March 26, 2016, the city announced that it would preserve the Kadonowaki Elementary School as one of the disaster ruins.

Despite repeated official announcements over loudspeakers on March 11, 2011 not to use vehicles for the evacuation, there was heavy use of vehicles in Ishinomaki, which on March 11, 2011 led to traffic jams and, as a result, many deaths.

Fatalities were also caused by the fact that those who had already been successfully evacuated uphill left their place of refuge after the arrival time of the tsunami estimated by the JMA had passed without the tsunami becoming visible. Also, some people who had initially remained on higher ground during the floods returned to lower areas around 5 p.m. when the water withdrew, whereupon the fourth and fifth tsunami waves again flooded parts of the city and killed many more people.

Ishinomaki can be used as an example that the evacuation of the low-lying areas during the Tōhoku tsunami did not take place everywhere. While the ground tremors triggered evacuations in Ishinomaki, this appears to have been a reaction to earthquake education rather than tsunami education, and people evacuated to local parks rather than purposefully escaping uphill. The evacuation training and disaster education of the schools in the city of Ishinomaki were geared towards earthquake events without taking tsunamis into account.

- Elementary School Ōkawa Incident

Of the 635 and 221 children, students and teachers, respectively, who were killed or injured by the tsunami in Japan , according to the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (according to other sources, there were 733 dead and missing among students and teachers) , a particularly large number were from the Grundkawa primary school, which was 4 to 5 km from the mouth of the Kitakami on the Pacific coast inland on the Kitakami River in Ishinomaki-Kamaya (釜 谷), a rural area characterized by population decline . The Kamaya area had never been hit by a tsunami before. Many people in the area saw the school as a haven in the event of a disaster. The school was located between a mountain and the river dam, so the advance of the tsunami could not be observed there.

The school evacuated its students to the playground just 5 minutes after the earthquake (at 2:46 p.m.). But in the tsunami the school lost 74 (4 of whom were missing) of its 108 students and 10 (of which one was missing) of its 11 teachers, after they did not follow the steep hill, which climbed to 220 m, directly behind after about 50 minutes They climbed up to the school, but went to a small lookout point on the main street of Kamaya at the level of the Kitakami bridge, only 6 m higher than the school and 200 m away from the school, and on the way there they went from the one at the time of theirs The embankment of the Kitakami tsunami had already been washed away. The tsunami hit the school from the Kitakami River at 3:37 p.m., after a delay of at least 50 minutes after the earthquake, as a stopped clock in a classroom on the second floor recorded. The tsunami flooded the two-story school building from the Kitakami River up to the ceiling of the second floor or also flooded its roof. The school building was badly damaged. A run-up height of 9.3 m was measured on a slope behind the school. Most of the surviving children had fled to the mountain behind the school. Prior to the 2011 disaster, the school had not conducted evacuation drills, nor had it had any tsunami plans. Of all the fatalities in the tsunami of March 11, 2011, with the exception of 74 pupils from Ōkawa elementary school, only one other child was in the care of his teachers when it died in the disaster.

Due to the low number of school leavers from Ōkawa Elementary School, Ōkawa Junior High School was closed in March 2013. It was decided that the elementary school, which opened in 1985, would be closed on the 7th anniversary of the 2011 disaster, that the students would be united with those of the Futamata elementary school and that the old school name of Ōkawa elementary school would no longer exist. The old school building, devastated by the tsunami, on the other hand, was intended to be preserved as a memorial after long and controversial discussions by resolution of the Ishinomaki city administration from the end of March 2016. The school building, which has been preserved as a disaster ruin, is given great importance in disaster risk education in order to pass on the tragedy and to convey lessons learned from it for disaster risk management and disaster control. The school building is to be completely preserved and the site is to be developed into a park.

23 months after the tsunami, Ishinomaki City Council announced the establishment of a so-called Examination Board for the Elementary School Ōkawa Incident, which evaluated documents and conducted interviews for a year, and the results of which were published in a 200-page report in February 2014. In March 2014, the families of 23 children who died in Ōkawa Elementary School from the tsunami brought a class action lawsuit against the Ishinomaki city government and Miyagi Prefecture in Sendai District Court, accusing them of negligence for the deaths of the children and sued for 100 million yen in compensation for each lost child. Their argument that the school staff should have evacuated the children more quickly was countered by the local and prefectural governments that the size of the tsunami and its advance so far inland to the school were unpredictable. On October 26, 2016, the Sendai District Court ruled on the case, in which the plaintiff parents of the 23 elementary school children were right and the sum of 1.4 billion yen was awarded as compensation. The lawsuit brought by the parents of the deceased Ōkawa elementary school students was seen as appropriate to give the school building an alternative meaning so that it is no longer the focus of discussions about whether it should be preserved or demolished, but instead the focus of the civilian one The survivors' claim against the city and prefecture governments.

In other, similar disputes, the relatives of five children from Hiyori Kindergarten in Ishinomaki who died in the disaster won their lawsuits against the kindergarten at Sendai District Court, whereupon the two parties were settled at Sendai Higher Court . In 2008, it was announced that the Sendai High Court (仙台 高 裁) ruled on the civil lawsuit on the Elementary School kawa incident, confirming the importance of the school's responsibility to protect the life of their school in the event of a disaster. The ruling explicitly pointed to the systematic lack of precaution among school principals, vice rectors, curriculum coordinators and other school principals. The High Court went further in assigning the blame to the school and local authorities than the lower court ruling, which merely recognized errors of judgment by teachers who, after it became clear that a tsunami was imminent, took students to a location other than the one behind the school where they would have been safe from the tsunami. The judgment of the High Court is considered to be of great importance to Japanese schools across the country. It encourages schools to scrutinize disaster control measures and, taking full account of the local conditions and topography of the schools and surrounding areas, to determine whether schools are adequately prepared to protect the lives of their students.

Relocation and Reconstruction

On the peninsula, deep, elongated harbors caused waves to rise and destroy villages on low, flat land. However, the neighboring mountains made it easy to evacuate to higher areas, so that the loss of human life remained comparatively low. As far as they could access the boats, the residents could go back to work. Despite the material damage, there was a strong desire for reconstruction early on in this region compared to other affected areas.

The disaster-hit population in Ogatsu District decided against the local government's resettlement plan and decided to rebuild the city in its original location.

In order to revitalize Ishinomaki's industry, the increase in the earthquake-sunk floor was seen as a necessary condition. A few years after the disaster, such a large reconstruction project was expected to take several years. A longer period than after the 1995 Kobe earthquake was estimated for the recovery of the job situation in Ishinomaki .

- Gallery: Devastation in Ishinomaki after the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011:

Aerial view of the port of Ishinomaki with stranded ships like the cargo ship CS Victory (Photo: March 20, 2011)

View from Hiyoriyama-kouen-Park (日 和 山 公園) down to the destruction in Minamihama, weeks after the tsunami during the heyday of the Sakura (Photo: April 25, 2011)

The symbol of the Canned Whale Meat Factory Kinoya Seafood Co. Ltd. In the form of an oversized whale meat can, the tsunami washed up about 300 m from the company premises to Prefecture Street 240, where it became a popular photo object until the evacuation started in June 2011.

traffic

- Train:

- Street:

- Sanriku-Jukan Highway

- National road 45,108,398

Town twinning

-

Hitachinaka , Japan

Hitachinaka , Japan -

Kahoku , Japan

Kahoku , Japan -

Civitavecchia , Italy

Civitavecchia , Italy -

Wenzhou , People's Republic of China

Wenzhou , People's Republic of China -

Everett , United States

Everett , United States

sons and daughters of the town

- Jun Azumi (* 1962), politician

- Shiga Naoya (1883–1971), one of the most important Japanese writers of the 20th century

- Hiroki Ōmori (* 1990), football player

- Ryūnosuke Sugawara (* 2000), football player

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Teppei Kobayashi, Yasuaki Onoda, Katsuya Hirano, Michio Ubaura: Practical Efforts for Post-Disaster Reconstruction in the City of Ishinomaki, Miyagi . In: Journal of Disaster Research . tape 11 , no. 3 , 2016, p. 476-485 , doi : 10.20965 / jdr.2016.p0476 . (Published online January 2016).

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online August 15, 2017).

- ↑ a b Katerina-Navsika Katsetsiadou, Emmanuel Andreadakis, Efthimis Lekkas: Tsunami intensity mapping: applying the integrated Tsunami Intensity Scale (ITIS2012) on Ishinomaki Bay Coast after the mega-tsunami of Tohoku, March 11, 2011 . In: Research in Geophysics . tape 5 , no. 1 , 2016, p. 5857 (7-16) , doi : 10.4081 / rg.2016.5857 . , License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). Special issue on Mega Earthquakes and Tsunamis.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Stuart Fraser, Alison Raby, Antonios Pomonis, Katsuichiro Goda, Siau Chen Chian, Joshua Macabuag, Mark Offord, Keiko Saito, Peter Sammonds: Tsunami damage to coastal defenses and buildings in the March 11th 2011 Mw9.0 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami . In: Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering . tape 11 , 2013, p. 205-239 , doi : 10.1007 / s10518-012-9348-9 . (Published online March 27, 2012).

- ↑ Mayuka Yamazaki (with the assistance of Fumika Yoshimine and Hiroko Yanagisawa): "Rebuilding the Tsunami-Stricken Onagawa Town", [July 2013?]. ETIC (Entrepreneurial Training for Innovative Communities)> Disaster Recovery Leadership Development Project> Case Studies from Tohoku> Case3 (URL: http://www.etic.or.jp/recoveryleaders/en/wp-content/uploads/Rebuilding-Onagawa. pdf )

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (Published online March 19, 2014).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 997, Figure 8. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1002, Figure 13. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1004, Figure 15. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ^ Structural Measures Against Tsunamis . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 1, pp. 25–32 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO .; here: p. 29, Map 1.2.

- ↑ M. Ando, M. Ishida, Y. Hayashi, C. Mizuki, Y. Nishikawa, Y. Tu: Interviewing insights regarding the fatalities inflicted by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. tape 13 , September 6, 2017, p. 2173-2187 , doi : 10.5194 / nhess-13-2173-2013 . , License: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0); here: 2179, Fig.2 a) ("Yamada").

- ↑ Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (Published online March 19, 2014). License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3192, Figure 11.

- ↑ Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (Published online March 19, 2014). License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3191, Figure 9.

- Jump up ↑ Nobuo Mimura, Kazuya Yasuhara, Seiki Kawagoe, Hiromune Yokoki, So Kazama: Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami - A quick report . In: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change . tape 16 , no. 7 , 2011, p. 803-818 , doi : 10.1007 / s11027-011-9304-z . (Published online May 21, 2011).

- ^ A b Structural Measures Against Tsunamis . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 1, pp. 25–32 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b c d Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online July 7, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d e Lori Dengler, Megumi Sugimoto: Learning from Earthquakes - The Japan Tohoku Tsunami of March 11, 2011 . In: EERI Special Earthquake Report . November 2011, p. 1-15 . , Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI).

- ↑ a b c d Livelihood and Job Creation . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 24, pp. 211–219 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 157 報) ( Memento of March 18, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento of March 18, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 157th report, March 7, 2018.

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, April 10, 2011, archived from the original on May 1, 2011 ; Retrieved May 3, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

- ^ Cultural Heritage and Preservation . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 35, pp. 323–330 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 124 報) ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 124th report, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, May 20, 2011, archived from the original on June 19, 2011 ; Retrieved June 19, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

-

↑ a b 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 158 報) ( Memento from October 3, 2018 on WebCite )

ホ ー ム> 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) 被害 報> 【過去】 被害 報>平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 被害 報 157 報 ~ (1 月 ~ 12 月) ( Memento from October 3, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 158th damage report , September 7, 2018. - ↑ 平 成 22 年 国 勢 調査 - 人口 等 基本 集 計 結果 - (岩手 県 , 宮城 県 及 び 福島 県) ( Memento from March 24, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF, Japanese), stat.go.jp (Statistics Japan - Statistics Bureau , Ministry of Internal Affairs and communication), 2010 Census, Summary of Results for Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, URL: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/index.html .

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 記録 集 ( Memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), March 2013, here in Chapter 3 (第 3 章 災害 の 概要) the subsection 3.1 / 3.2 (3.1被害 の 概要 /3.2 人 的 被害 の 状況) ( PDF ( memento from March 23, 2018 on WebCite )).

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online on August 15, 2017), here p. 22, table 2.

- ↑ a b 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 153 報) ( Memento of March 10, 2016 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 153. Report, March 8, 2016.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 3.

- ^ Community-Based Disaster Risk Management . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 6, pp. 65–69 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b Kimiaki Sato, Michio Kobayashi, Satoru Ishibashi, Shinsaku Ueda, Satoshi Suzuki: Chest injuries and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake . In: Respiratory Investigation . tape 51 , no. 1 , March 2013, p. 24–27 , doi : 10.1016 / j.resinv.2012.11.002 . (Published online on). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

- ↑ Nam Yi Yun, Masanori Hamada: Evacuation Behavior and Fatality Rate during the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Earthquake Spectra . tape 31 , no. 3 , August 2015, p. 1237-1265 , doi : 10.1193 / 082013EQS234M . , here table 2.

- ↑ a b c d S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 48f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Isao Hayashi: Materializing Memories of Disasters: Individual Experiences in Conflict Concerning Disaster Remains in the Affected Regions of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami . In: Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology [ 国立 民族 学 博物館 研究 報告 ] . tape 41 , no. 4 , March 30, 2017, p. 337-391 , doi : 10.15021 / 00008472 .

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 32.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 35f.

- ^ S. Fraser, GS Leonard, I. Matsuo, H. Murakami: Tsunami Evacuation: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11th 2011 . In: GNS Science Report 2012/17 . Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012, ISBN 978-0-478-19897-3 , ISSN 1177-2425 , 2.0, pp. I-VIII + 1–81 ( massey.ac.nz [PDF; accessed on June 29, 2018]). ; here: p. 26.

- ↑ Yoshinobu Tsuji, Kenji Satake, Takeo Ishibe, Tomoya Harada, Akihito Nishiyama, Satoshi Kusumoto: Tsunami Heights along the Pacific Coast of Northern Honshu Recorded from the 2011 Tohoku . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. 12 , 2014, p. 3183-3215 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0779-x . (Published online March 19, 2014). License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3192, Figure 10.

- ↑ Anawat Suppasri, Nobuo Shuto, Fumihiko Imamura, Shunichi Koshimura, Erick Mas, Ahmet Cevdet Yalciner: Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami: Performance of Tsunami Countermeasures, Coastal Buildings, and Tsunami Evacuation in Japan . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 170 , no. 6-8 , 2013, pp. 993-1018 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-012-0511-7 . (Published online on July 7, 2012), here: p. 1009, Figure 21. License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

- ↑ a b c d Shunichi Koshimura, Nobuo Shuto: Response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster . In: Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society A Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences . tape 373 , no. 2053 , 2015, p. 20140373 , doi : 10.1098 / rsta.2014.0373 . (Published online September 21, 2015).

- ^ A b c The Education Sector . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 8, pp. 77–82 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b c d e f g The school beneath the wave: the unimaginable tragedy of Japan's tsunami ( Memento of 27 March 2018 Webcite ) (English), theguardian.com, August 24, 2017 by Richard Lloyd Parry.

- ↑ a b c d e f Court ruling anticipated on responsibility of school over student tsunami deaths ( Memento of 27 March 2018 Webcite ) , mainichi.jp (English), October 25, 2016th

- ↑ a b Evacuation . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 11, pp. 99-108 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ a b c d e Akemi Ishigaki, Hikari Higashi, Takako Sakamoto, Shigeki Shibahara: The Great East-Japan Earthquake and Devastating Tsunami: An Update and Lessons from the Past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923 . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 229 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 287-299 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.229.287 . (Published online April 13, 2013).

- ↑ a b c Akemi Ishigaki, Hikari Higashi, Takako Sakamoto, Shigeki Shibahara: The Great East-Japan Earthquake and Devastating Tsunami: An Update and Lessons from the Past Great Earthquakes in Japan since 1923 . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 229 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 287-299 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.229.287 . (Published online April 13, 2013). With reference to: 防災 対 策 庁 舎 の 悲劇 ◆ 宮城 ・ 南 三 陸 ( memento from August 15, 2018 on WebCite ) , memory.ever.jp, [undated].

- ↑ a b c Abdul Muhari, Fumihiko Imamura, Anawat Suppasri, Erick Mas: Tsunami arrival time characteristics of the 2011 East Japan Tsunami obtained from eyewitness accounts, evidence and numerical simulation . In: Journal of Natural Disaster Science . tape 34 , no. 1 , 2012, p. 91-104 , doi : 10.2328 / jnds.34.91 .

- ↑ a b Tsunami-hit Okawa Elementary holds ceremony ahead of closure in March , The Japan Times, February 24, 2018.

- ↑ High court ruling on 2011 tsunami deaths a warning to schools nationwide ( Memento from July 2, 2018 on WebCite ) (English), mainichi.jp (Mainichi Japan), Editoral, April 27, 2018. Japanese-language version: 防災 責任 認 めた 大川 小 判決 教育 現場 へ の 重 い 警鐘 だ ( Memento from July 2, 2018 on WebCite ) (English), mainichi.jp, April 27, 2018.

- ^ Relocation in the Tohoku Area . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 33, pp. 307–315 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed on April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ After Japan's earthquake and tsunami - week 5 ( memento from July 9, 2018 on WebCite ) , nbcnews.com, update from April 8, 2011.

- ↑ Japanese PM thanks US troops during visit to devastated region ( July 9, 2018 memento on WebCite ) , stripes.com, April 10, 2011, by Seth Robson.

- ↑ www.wenzhou.gov.cn: City friendships . Retrieved July 11, 2019.

Web links

- 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図 , 国土 地理 院 ( Kokudo Chiriin , Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, formerly: Geographical Survey Institute = GSI), www.gsi.go.jp: 地理 院 ホ ー ム> 防災 関 連> 平 成 23 年 (2011年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 に 関 す る 情報 提供> 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図: