New Synagogue (Berlin)

| New synagogue | |

|---|---|

| Construction time: | 1859-1866 |

| Architect : | Eduard Knoblauch , Friedrich August Stüler |

| Style elements : | Orientalizing architecture |

| Location: | 52 ° 31 '30 " N , 13 ° 23' 39.6" E |

| Address: | Oranienburger Strasse 28-31 10117 Berlin Berlin , Germany |

| Purpose: | Conservative Judaism / egalitarian synagogue |

| Website: | www.or-synagoge.de |

The New Synagogue on Oranienburger Strasse in the Spandauer Vorstadt in the Mitte district ( Mitte district ) of Berlin is a building of outstanding importance for the history of the Jews in Berlin and an important architectural monument. It was inaugurated in 1866. The remaining part of the structure is a listed building . It was reopened in 1995 after restorations, but not inaugurated again. The architects were Eduard Knoblauch and Friedrich August Stüler .

Planning and construction

In the middle of the 19th century, the Jewish community in Berlin had grown significantly. By 1860 it had about 28,000 members. The time only - later "Old Synagogue" - called Synagogue stood in the Heidereutergasse, near the Hackescher Markt in Berlin-Mitte and not offered more adequate space. After the congregation had acquired a plot of land on Oranienburger Strasse in 1856, in a residential area with a strong Jewish feel, an architectural competition for the new synagogue was announced on April 7, 1857. The chairman of the competition commission was the busy architect Eduard Knoblauch , a member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts since 1845 . The submitted drafts could not convince. Knoblauch was commissioned with the planning himself - he had previously successfully managed the renovation of the old synagogue and the new building of the Jewish hospital. When he became seriously ill in 1859, he was replaced by the Prussian court building officer and "King's architect" Friedrich August Stüler , who was friends with Knoblauch. He took over the construction according to his ideas and designed the interior design. Knoblauch's employee Hermann Hähnel was in charge of construction .

The construction work began after the laying of the foundation stone on May 20, 1859; The topping-out ceremony was celebrated in July 1861 . Then there were delays. The interior was unusually lavish and there were material shortages during the German-Danish War of 1864. After Stüler's death in 1865, Edward's sons Gustav and Edmund completed the building. The finished synagogue could not be inaugurated until the Jewish New Year celebrations on September 5, 1866 - the 25th Elul 5626 according to the Jewish calendar . The then Prussian Prime Minister and later Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was present at the ceremony.

Eduard Knoblauch based his design on elements in an oriental style ; he was particularly inspired by the Alhambra in Granada in southern Spain . This style looked strange in the Prussian surroundings at the time, but was not uncommon in the construction of synagogues in the mid-19th century.

The cost was originally estimated at 125,000 thalers , which increased sixfold by the time it was completed, to a total of 750,000 thalers.

“If you are interested in architectural things, in solving new, difficult tasks within the art of building, we recommend a visit to this rich Jewish house of God, which in terms of splendor and magnificence of proportions far overshadows everything that the Christian churches of our capital city have to offer have to show. "

On September 6, 1866, one day after the inauguration, the National-Zeitung ruled :

“The new church is a pride of Berlin's Jewish community, but more than that, it is an ornament of the city, one of the most remarkable creations of modern architecture in the Moorish style and one of the most distinguished construction companies that has carried out the north German residence in recent years a fairytale-like building, which in the middle of a sober part of our residence introduces us to the fantastic wonders of a modern Alhambra with the graceful light columns, the sweeping round arches, the colorful arabesques, the manifold articulated carvings, with all the thousands of magic of the Moorish style. "

The Vossische Zeitung wrote:

“The light flows through the colorful panes, magically subdued and transfigured. Ceilings, walls, columns, arches and windows are decorated with lavish splendor and with their gilding and decorations form a wonderful arabesque wreath with a fairy-like, unearthly effect, intertwining into a harmonious whole. "

architecture

Layout

The floor plan of the Berlin synagogue is based on the particular shape of the property, which is elongated and angled from Oranienburger Straße backwards in the longitudinal axis to the right by approx. 15 degrees. Behind the front building on Oranienburger Straße there is a polygonal, domed vestibule, the vestibule and the small synagogue on the front or weekday. Until 1958, the building of the main synagogue with a hall for weddings and a rabbi room was attached. The street front is 29 meters wide and the whole property is 97 meters long. The dimensions of the main synagogue until its final destruction were: length 45 meters, width 40 meters, with the large hall of the main synagogue offering 3000 seats (according to another source: divided into 1800 seats for men and 1200 seats for women).

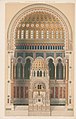

Exterior architecture

The Berlin synagogue on Oranienburger Strasse is the earliest example of the combination of a two-tower facade, dome and three-part portal. The facade facing Oranienburger Straße is richly structured with shaped stones and terracottas , accented by colored glazed bricks. The three-axis central wing is flanked by protruding side projections with domed, octagonal tower attachments. The two kiosk-like and tempietto-like tower attachments are each placed on square side elevations, with the small columns in front of the tower attachments being kept in the Alhambra style. The motif of the three arches characterizes the facade. This motif can be seen both in the three-arcade entrance and in the three arched windows on the upper floor of the middle wing, the scales of which are in turn divided into three arches. The tambour of the dome takes up the same motif, so small, three-part arched windows can be seen in the tambour. The drum dome over the vestibule, covered by gilded ribs , is exactly 50.21 meters high at its highest point and forms the highlight of the building that can be seen from afar. The builder used Indian-Islamic architecture for the shape of the dome, based on the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

Above the entrance there is the inscription in gold-colored letters: פתחו שערים ויבא גוי צדיק שמר אמנים. It is the verse 26.2 EU from the book of Isaiah in Hebrew . His German translation reads: "Open the gates, that the just people will move in, that will keep their loyalty."

Interior design

The interior design of the main synagogue appeared before its final destruction in 1958, like a three-aisled sacred building , which was divided into five bays, with both a glass hanging dome and a barrel vault in the main aisle from one bay to the other.

Two technical facilities were remarkable. One special feature was the abundant use of cast iron as a building material. The side aisles were divided by painted cast-iron pillars, which appeared as ten painted cast-iron arcades in the basement and five arcades on the upper floor. The arch approaches of the lower row of pillars supporting the galleries appeared in both Moorish and Indian architecture. Additional cast iron was invisibly used in the construction of the hall ceiling and the hanging domes. The height to the top of the flat and hanging dome was 24.32 meters.

The second technical peculiarity was the well-thought-out lighting management of the glass hanging domes and the side windows. The glazed round openings of the domes had double glazing, the outer panes consisted of simple light-colored glass and the panes of glass on the inside of the dome were colored. Between these two panes of glass was gas lighting that made the colored inner panes shine brightly from the inside.

Furnishing

The models for the Aron ha-Qodesch were the basic shape of a Christian altar canopy and the pavilion of the Lion Court in Granada. The Aron ha-Qodesch showed circular arcades that were reminiscent of the arcades of the Lion Court of the Alhambra. The upper end of the Aron ha-Qodesch had a ribbed dome on a column wreath, with the ornamentation of the half-dome of the Torah shrine taking up the division of the large outer main dome with ribs and a honeycomb pattern. The ornamentation of the half-dome of the Torah shrine showed a star pattern, which consisted of two nested squares. Rosettes, tendrils and plant ornaments enriched the ornamentation.

Use and destruction

Anti-Semites found the magnificent building with the shiny gold dome as a provocation. But it also sparked heated discussions among the Jewish population. Liberal Jews voiced the objection that the unfamiliar Moorish architectural style emphasized the strangeness of the Jewish religion and thus hindered the desired integration process. Conservative Jews expressed reservations about the various innovations in the worship service and interior decoration. The parish council had appointed the reform-minded Rabbi Joseph Aub to the New Synagogue. The service was held according to the New Rite. This caused tensions in the congregation, in particular a church service with organ music - the instrument was installed in 1868 - many found it unsuitable. In the new building they saw a "nice theater, but not a synagogue [...]". The differences of opinion eventually led to a split. In 1869 Adass Yisroel was formed , a group of dissatisfied conservative members who left the community in 1872 and received official approval as an Israelite synagogue community in 1885.

The majority, however, viewed the building with pride and satisfaction, as a symbol of the importance and self-confidence of the Jewish community in Berlin. The largest, most expensive and most splendid Jewish place of worship in Germany, also an example of the application of the most modern building techniques, became a highly regarded attraction.

During the nationwide pogroms on the night of November 9-10, 1938 , members of the SA began to set fire to the New Synagogue. The district chief of the nearby police station 16, Wilhelm Krützfeld , confronted the arsonists, referred to the monument protection for the building that had existed for decades, alerted the fire brigade, which was able to extinguish the fire inside the building, and thus saved the synagogue from destruction. Krützfeld, who had acted according to the regulations, was then subjected to frequent harassment at work. A plaque commemorates his - for the political situation at the time - unusually courageous intervention. Since 1993 - in commemoration of this act - the training facility of the Schleswig-Holstein State Police has been called "State Police School Wilhelm Krützfeld".

After the consequences of the fire had been eliminated, the New Synagogue could be used again for church services since April 1939. The dome had to be painted over with camouflage paint because of the threat of Allied air raids . After a last service in the small prayer room on January 14, 1943, the Wehrmacht took over the building and set up a uniform warehouse here. At the beginning of the so-called Battle of Berlin by the British Bomber Command , the synagogue suffered severe damage on the night of November 23, 1943. Further damage was caused to the structure when the ruins were used as a supplier of building materials after the war.

After the end of the war, the few surviving Jews in the city founded a new Jewish community based in the synagogue's administration building on Oranienburger Strasse. The first thing was to create suitable conditions for Jewish life in Berlin again and, on the other hand, to prepare emigration for those who did not want to stay. In the summer of 1958, damaged parts of the building were completely removed because of the risk of collapse and on the grounds that reconstruction was not possible. Only the building fabric on the street remained - as a memorial against war and fascism.

There is a “historical” black and white photo of the attempt to destroy the synagogue in 1938, “The New Synagogue in Flames”. Decades later, a closer examination of the photography and historical research led Heinz Knobloch to come to the conclusion that the synagogue in the photo did not correspond to its actual condition in 1938. The photo was apparently heavily retouched in the post-war period .

Racism incident on October 4, 2019

On October 4, 2019, there was another attack on the New Synagogue. A 23-year-old Syrian was " Allahu akbar " (Allah is great ') calling exceeded a barrier and was with a knife on the physical protection running up -Staff. Nobody got hurt. After an investigation, the man was released. Josef Schuster spoke of a “failure” and “negligent” behavior of the Berlin public prosecutor's office.

Centrum Judaicum

history

After there had even been a tendency to demolish the entire building and erect a memorial stone in its place, the " New Synagogue Berlin Foundation - Centrum Judaicum" was only founded in 1988 in connection with commemorative events for the 50th anniversary of the pogrom night Rebuilding the new synagogue and creating a center for the care and preservation of Jewish culture.

Part of the new climate was that the GDR employed the American Rabbi Isaac Neuman from September 1987 to May 1988 to support community life. He was entitled to a company car and apartment as well as a domestic servant who, however, worked for the MfS . A symbolic laying of the foundation stone for the reconstruction of the ruin took place on November 10, 1988. The type of restoration had previously been controversial. A complete restoration to the original state was rejected - it could have been misunderstood as an attempt to suppress the sufferings of the past and possibly to forget. However, the intention was to have a memorial for permanent remembrance at the same time as the building.

So it was decided to make both visible - the once magnificent architecture and the violent destruction. The representative street front with the main dome was reconstructed true to the original. A permanent exhibition provides information about Jewish life in Berlin. Some architectural fragments and rediscovered parts of the interior are also shown. In the open space in the depths of the property, stones mark the extensive floor plan of the former main synagogue. The renovation work was finished in 1993. The restored building, protected against current threats by extensive security measures, was handed over to the foundation on December 16, 1994 and opened on May 7, 1995. It was not consecrated again as a synagogue, but contains a small prayer and devotion room. Jewish community facilities, restaurants, cafés and the Jewish gallery are in the immediate vicinity.

Exhibitions

Since 1995 the permanent exhibition of the Centrum Judaicum and special exhibitions have been shown in the former administration building of the synagogue. Initially, the exhibition showed a broad spectrum of Judaica , including manuscripts, printed matter and sacred objects, and presented the history of the Jews in Berlin and Prussia. The opening of the Jewish Museum Berlin in 2001 made it possible to relieve the exhibition in terms of content and history focus on the New Synagogue and its community. The permanent exhibition was revised and reopened in a new form in 2018.

2011 took place under the title Good Business. Art trade in Berlin 1933–1945 an exhibition in Berlin instead of in the Active Museum in the Centrum Judaicum and in the Berlin State Archives . At the same time, it was “a reminder to clarify the [...] outstanding property issues due to ' cultural assets confiscated due to persecution ' [...]”. The exhibition treated among other linearisation of the gallery Matthiesen of Franz Catzenstein , but also showed that other under the terror of the Nazi regime had suffered.

Church services

Today church services are held regularly under the direction of Rabbi Gesa Ederberg and Cantor Avitall Gerstetter .

literature

- Daniela Gauding, Hermann Simon : The New Synagogue Berlin. "... for the glory of God and for the adornment of the city" . Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-942271-25-7 .

- Hermann Simon: The New Synagogue, Berlin. Past - present - future . Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-89468-036-9 .

- Hannelore Künzl: Islamic style elements in synagogue construction of the 19th and early 20th centuries . In: Judaism and the Environment . tape 9 . Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1994, ISBN 3-8204-8034-X , pp. 313 .

- Klaus Arlt, Constantin Beyer: Evidence of Jewish Culture. Memorial sites in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Brandenburg, Berlin, Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony and Thuringia . Tourist-Verlag, Erfurt 1992, ISBN 3-350-00780-5 , p. 142 ff .

- Knoblauch: The New Synagogue in Berlin . In: Journal of Construction . 1866, col. 3–6, 481–486 , plates 1–6 , urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-87705 (year 16; in the holdings of the Central and State Library Berlin ).

Web links

- Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- Internet presence of the "New Synagogue Berlin Foundation"

- Website of the minyan

- historical photos: New Synagogue ruins, 1988

- Deutschlandradio Kultur In conversation on July 22, 2016: Historian Hermann Simon. The Centrum Judaicum was my baby , moderated by Katrin Heise

- BStU , topic: New Synagogue, "Crystal" campaign and a grand plan

Individual evidence

- ↑ Uwe Kieling: Berlin - Builders and Buildings: From Gothic to Historicism . 1st edition. Tourist Verl., Berlin; Leipzig 1987, ISBN 3-350-00280-3 , p. 207 .

- ↑ 1865 in the Kreuzzeitung about the synagogue under construction

- ↑ Künzl, p. 318 ff.

- ↑ Sights . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1875, part 4, p. 173. “contains 300 seats” (cut off from p. 172; left column above).

- ↑ Künzl, p. 313 ff.

- ↑ Künzl, p. 323.

- ↑ Proud and Confident , Jüdische Allgemeine , September 5, 2016, accessed November 6, 2019.

- ^ A New Synagogue for Berlin. At: Deutschlandfunk Kultur , September 5, 2016, accessed on November 6, 2019.

- ↑ a b Künzl, p. 319.

- ↑ Künzl, p. 320.

- ↑ Künzl, p. 321.

- ↑ Künzl, p. 322 ff.

- ↑ Künzl, p. 322.

- ↑ cf. Heinz Knobloch : The courageous district chief. Unusual moral courage at Hackescher Markt . 2nd, expanded edition. Morgenbuch Verla, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-371-00373-6 .

- ↑ Svetlana Boym: Jüdisches Berlin: Von Retouch und Leerstellen , in: Zeitschrift Das Jüdische Echo , Vienna 2014, Vol. 63, pp. 140 f.

- ↑ Central Council of Jews in Germany Kdö.R: Man pulls knife in front of synagogue. October 5, 2019, accessed June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ The police have to release the man with the knife. Retrieved June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander Muschik: The SED and the Jews. In: bpb.de. Federal Agency for Civic Education, April 20, 2012, accessed on November 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Ulrike Offenberg: "Be careful against those in power." The Jewish communities in the Soviet Zone and the GDR 1945–1990 . Aufbau-Verlag , Berlin 1998, ISBN 978-3-351-02468-0 , p. 216 .

- ^ Franz Sommerfeld: 3,000 guests from all over the world came to Berlin for the opening of the Centrum Judaicum: a hub for Jewish life. In: Berliner Zeitung . May 8, 1995. Retrieved November 15, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Judith Leister: Wound and memorial. The Berlin New Synagogue tells its own history and the eventful fate of its community in its permanent exhibition. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . September 27, 2018, p. 22 , accessed November 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Reopening of the permanent exhibition. (No longer available online.) In: centrumjudaicum.de. July 5, 2018, archived from the original on October 1, 2018 ; accessed on October 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Christine Fischer-Defoy, Kaspar Nürnberg (ed.): Good business. Art trade in Berlin 1933–1945 . Active Museum Fascism and Resistance in Berlin, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-034061-1 (catalog for the exhibition of the same name by the Active Museum in the Centrum Judaicum (April 10 - July 31, 2011) and in the Berlin State Archives (October 20 2011 - January 27, 2012)).

- ^ Bernhard Schulz: Berlin / dealers and stolen goods. Centrum Judaicum: The exhibition "Good deals" documents the Berlin art market from 1933 to 1945. In: Jüdische Allgemeine . Central Council of Jews in Germany Kdö.R, April 14, 2011, accessed on November 15, 2018 .