Bow (weapon)

The bow (plural: bow or bows), more seldom also called arrow bow for clarity , is a launching device for arrows . The bow maker is called a bogner . Since the end of the Paleolithic Age (30,000–10,000 BC), archaeological finds have proven the use of bows and arrows as hunting weapons . Since the later Neolithic Age , bows and arrows have also been used as weapons in armed conflicts. Today the bow is used as a piece of sports equipment for archery in some countries for archery hunting . As children's toys are a bow and arrow as Flitze- or crossbows referred.

Structure and principle of operation

A bow always consists of an elastic , stick-like object, the actual bow, the ends of which are connected by a cord, the bowstring . Traditional bows were made from wood , horn, and animal tendons ; A high-quality composite bow required an elaborate manufacturing process lasting several months. Modern bows usually consist of wood, glass fiber reinforced (GRP) or carbon fiber reinforced (CFRP) plastic composites.

Components, terms and parameters

The bow itself can be divided into five sections: a mostly rigid middle part that serves as a handle for the archer (handle) , two flexible limbs connected to it and the two ends of the bow, the tips or cams , to which the bowstring is attached. When attaching the bowstring, tensioning the bow, the limbs must be curved, this ensures the bow tension . When the bowstring is pulled out (pull-out) , the limbs are curved more and store energy . This provides for the acceleration of the arrow when you let go, the loosening of the string (the arrow). The principle is comparable to that of a leaf spring with initially degressive and, to a large extent, increasingly progressive spring characteristic. A bow is a power converter : the pulling work of the archer, which is slowly applied when it is pulled out and stored in the bow, is converted into a fast limb movement in the shortest possible time and transferred to the arrow. Therefore, a drawn bow must never be released without an arrow (empty shot) - there is a risk of breakage and injury! The entire stored energy is discharged almost instantaneously exclusively in the bow material due to the lack of arrow mass as an inert counterweight. The inert masses of the accelerated tendons and limbs themselves have only a laxative and braking effect. The bow can explode into several parts.

Because an arrow is not accelerated by explosive propellants like a projectile, but by the limbs , a bow does not shoot - a bow "throws".

The holding force required when fully extended is called the pulling weight and, for historical reasons, is mainly given in pounds sterling . The maximum possible pulling weight of a bow is largely determined by the stiffness of the limbs in relation to the bow length . There may be more than 100 pounds, which a force of 444 N corresponds.

The characteristic values of a bow are usually given on the side facing the archer , the belly of the bow near the handle, in hand-made bows together with the signature of the bow maker . The specification of the draw weight applies to a certain extension length , mostly for the standard extension length of 28 inches (~ 71 cm); for bows specially built for the customer ( custom bows ) for its extension length. The extension length is a standardized measured length from the lowest point of the handle to the nocking point on the string at the archer's anchor point when the bow is extended, plus 1 3/4 inches. The addition value provides approximate comparability with an old definition, which measures up to the leading edge of the bow at the height of the arrow rest. Each shooter has an individual extension length. When pulling the bow beyond the specified extension length, the pulling weight and thus the effort increases rapidly, so-called stacking occurs . The controlled dosage of force and thus the control over a constant arrow speed - and with this in turn the accuracy - decrease. There is a risk of bow breakage and injury. With modern sports bows, a clicker signals to the archer that a special length of pull has been reached and thus that his anchor point has been reached .

A typical characteristic value on a limb is, for example: 66 ″ 46 # @ 28 ″ . Spoken: "66 inch bow length, 46 libs (English pounds) draw weight at 28 inch extension."

The most common form of bow is the right-hand bow . This means that the archer holds the bow with his left hand ( bow hand left) and pulls out the bowstring with his right hand ( pull hand right). The shooter is also known as a right-handed shooter . In the case of a left-handed bow or left-handed archer, the situation is reversed. The choice of bow is not only determined by the handedness of the archer, but also by the dominance of his eyes . The bowstring with the arrow is led to the dominant eye because it takes over the aiming.

Efficiency

For the resulting final speed of an arrow, in addition to the characteristic curve of the pulling weight curve (extraction work = stored energy), the efficiency is decisive, i.e. H. the ability with which the bow can convert the deformation energy stored in it through the pulling work into kinetic energy of the arrow. A part of the unusable energy dissipates in the acceleration of the limbs and tendons themselves, another part in the deformation work in the bow material by vibrations from the shock waves of the sudden discharge. The weight of the arrow also influences the efficiency of a bow: the heavier the arrow, the higher the efficiency, but the slower the arrow. The efficiency can only be determined or specified for a certain arrow weight. The auxiliary quantity is the so-called virtual mass of the arch, it is a constant arch property and characterizes the energetic quality of the arch. The lower the virtual mass, the higher the general efficiency and the less sensitive the bow reacts to weight fluctuations between different arrows. The virtual ground can be experimentally by comparing the arrow speeds and two different weights arrows of the masses and be determined - and hence the efficiency at a given arrow weight.

If the virtual mass is zero, the efficiency is always 100% and independent of the arrow weight.

If the virtual mass is known, the theoretical shooting speed without an arrow, the empty shot with arrow mass 0, can be calculated using a known speed of an arrow of the mass and, with the aid of this, the predicted arrow speed for any arrow weight :

It can be seen that with a low virtual mass, that is to say with a high energetic quality of the bow, the empty shot speed increases. In the case of the theoretically perfect bow with virtual mass zero, the firing speed increases to infinity with an empty shot. In this case, this means that the entire deformation energy stored during pulling out must suddenly be absorbed by the bow alone when it is released empty. Empty shots are therefore generally dangerous. You can destroy the bow and injure the archer or anyone present. The context shows that high-quality bows that can a. characterized by high efficiency, are particularly endangered by empty shots - only the high quality processing of good bows has a compensatory effect.

In contrast to the crossbow , many bows are not built symmetrically. One limb, usually the lower one, is more rigid than the other. The tiller is a key figure and a measure of the difference between the limbs . The necessity of the tiller results from the asymmetrical force points of the pressure point on the handle (bow hand) and the pull point on the string (pull hand). Depending on the type of bow and the selected finger grip of the pulling hand, they are not in the middle of the bow, but more or less deeper, so that the lower limb is more heavily loaded when it is pulled out and must therefore be more rigid. The grip on the tendon requires a different tiller than the Mediterranean indulgence , the use of a release requires a different one. The correct tillering of a bow is one of the highest manual skills of a bow maker. A poorly tuned bow loses efficiency, throws unsteadily or can break when pulled out or loosened.

History of the bow

Earliest finds

The oldest stone points, the interpretation of which as arrowheads is controversial, come from the Abri Sibudu (province of KwaZulu-Natal , South Africa) and are around 64,000 years old. In Europe, since the Solutréen (around 22,000 to 18,000 BC), there have been stalked flint tips that were probably arrowheads . They can be seen as the oldest indirect evidence of the arch's existence.

The oldest archaeological find interpreted as an arch comes from a gravel pit in Mannheim-Vogelstang from the time of 3n Magdalenian and was dated to an age of 14,680 ± 70 BP using the radiocarbon method (corresponds to a calibrated 16,055 ± 372 BC). The complete arch had a length of about 110 cm. Based on reconstructions, the performance is estimated to be about 25-30 pounds train weight (11 to 13 kg), which allows ranges of up to 80 m.

In addition, there is a possible arch depiction from the late Magdalenian period on an engraved limestone plate from the Grotte des Fadets , Vienne (France). However, the incision is not so clear that the interpretation could be taken for granted.

The flat arch with a D-shaped cross-section (also known as the “propeller type”) attested to in the Mesolithic was common until the Bronze Age . Arches of the Holmegård type are documented from the Ertebölle settlements of Maglemosegård, Ringkloster and Tybrind Vig in Denmark. They are mostly made of elm wood. Images of recurve bows (with a very likely composite construction ) have been on rock carvings in Spain since the early Neolithic .

Antiquity

The short arch probably developed with and in the steppe equestrian cultures and in the Middle East. The first evidence can be found on ancient representations and in the Kurgan . Because of the less favorable mechanical conditions compared to the longbow , they have bent back bow ends (recurves) and tendon / horn reinforcements ( composite bows ). Forms going back to this were adopted by the Greeks and Romans.

Arch finds from the Bronze Age , Iron Age and the Roman Empire are extremely rare in Central Europe, where longbows are still attested.

middle Ages

The bows of the Merovingians and Alemanni in particular have come down to us from the migration period , and the Stuttgart Psalter (around 830) shows battle scenes with bows and arrows between Avars and Franks .

The classic longbow developed in the European high and late Middle Ages into the English longbow with very high pulling weights, with which the chain armor commonly used at the time and, under favorable conditions, even the plate armor developed as a reaction could easily be penetrated. In the late Middle Ages, the bow began to be replaced by other long-range weapons such as crossbows and, above all, firearms.

Modern times

In the early modern period (approx. 1500 to 1790) the long bows were replaced. Longbows were still used in the English Civil War in the middle of the 17th century, but a short time later the longbow was finally ousted in England. Muskets gained ever greater firepower and range, and could penetrate armor more easily. In addition, the training of a longbow archer was much more complex and longer than that of a musket archer.

The bow as a weapon played a role in modern times mainly among the indigenous peoples of Africa, America and Australia. After all, he was no longer a common sight on the battlefields of Europe.

Since the 19th century archery and archery have been experiencing a boom again.

The bow had found its way into art, literature and legends since antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Arch types and areas of application

There is no single, universal classification system for bows. Arch types can be described using various properties such as the material used, the extension length, the shape of the arch and the like.

Primitive arc

A primitive bow (traditional bow; English: selfbow ) is made in its original form from a piece of wood, without a shot window (English: shelf ) and a grip area being formed. The simple bow therefore does not have an arrow rest, but the arrow is placed over the back of the bow hand.

"Primitive bow" as an archery class in today's traditional archery primarily means that only bows made exclusively from natural (ie pre-industrial) materials are permitted. Therefore, backing and handle leather can be present as long as they are made of natural materials.

The bowstring must also be made of natural materials (flax, linen, tendons, leather, skin, etc.). It is attached to the tips.

Woods used in Europe are z. B. yew, ash, maple and robinia .

Longbow

There are smooth transitions between the primitive bow and the long bow. A longbow can be a wooden bow (selfbow) without a shot window. Modern longbows usually consist of laminated strips of wood or with plastic inlaid on them . Glass fiber laminates are mainly used for the lining of the stomach and back, as well as carbon fibers as a layer laminate.

In traditional bow making, a distinction is made between English and American long bows. English longbows of the Mary Rose type are traditionally made of yew wood and have a deep D-shaped bow arm cross-section without a grip tape. The later Victorian English longbows have a lenticular cross-section over the entire length and a round handle, usually with a leather wrap. One speaks of a rod arch. American longbows have flat limbs with mostly rectangular limbs and a grip that is more adapted to the hand. The latter are also called flat arches .

Recurve / reflex bow

Recurve stands for the main feature of this type of bow, the bent back shape of the limbs, which point away from the archer when they are relaxed. The terms recurve bow and reflex bow are used synonymously.

The oldest evidence of this type of bow are rock paintings in the Spanish Levant (since the 6th millennium BC), on which warriors or hunters with recurve bows are depicted. Later depictions of recurve bows come from the Central German Bernburg culture , e.g. B. in the stone box from Göhlitzsch . At the latest with the Western European megalithic culture , the recurve bow came to Northern and Central Europe. Around 3000 BC They are found on megalithic graves of the Eastern European Maikop culture (e.g. in Klady) and then in the context of the Kura Araxas culture.

Around 2400 BC Akkadian kings present themselves with a recurve bow as a symbol of power. Later this is replaced by reflex arcs and a common part of depictions of kings in the Near East. Examples are among the Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians. In Thebes , Egypt , specimens of a type were found that were probably of Assyrian origin and date from around 1200 BC. Come from BC.

The recurve bow (reflex bow) stores more energy in the limbs and is therefore more efficient than the flat and long bow. The attached tendon also dampens the hand shock after the shot. While the bowstring swings freely in the longbow, in the recurve bow it rests on the limb ends (the "recurves"). By stretching the tendon when firing, some of the vibrations are absorbed by the bow. Due to the composite construction - which is the rule with reflex bows (see composite bows ) - this can be extended further than a long or flat bow and still has a softer extension. The strong pre-tensioning of the limbs, however, also requires the material to be able to withstand much greater stress.

As a take-down recurve is called recurve bows, which consist of a central part and two mountable limbs. The advantage of these bows, in addition to the smaller transport dimensions, is that a heavy center piece made of metal or plastic helps stabilize the bow when it is launched. Take-down recurves with a wooden middle section have advantages in terms of transport, and they also allow defective limbs to be replaced.

In sporting archery today, the recurve bow is understood to mean the Olympic recurve with visor and stabilizers. In contrast, the term blank bow is used today to denote the class of recurve bow without visor and stabilizers . In traditional archery, all bows without a visor are called bare bows.

Compound bow

→ Main article: Compound bow

The compound bow has rotating wheels at the ends of the bow, the so-called camwheels, or cams for short. They have two different diameters on which cables or tendons are rolled up. In the untensioned state, the string is rolled up on the larger of the two wheels. When the bow is drawn, the string is unrolled from the big wheel and the cable attached to the opposite limb is rolled up on the small wheel. The cams are also hung eccentrically .

Modern compound bows apply the law of leverage , just like a corrugated gear . The roller turning outwards is like a rigid lever that acts on the axis of rotation. The eccentric suspension of the rollers / cams changes the angle of attack and the lever arm, so the bow always works in the most effective range. If the rollers / cams are pulled outwards with the bowstring, the lever arm is extended. These mechanisms are implemented in a practical application in the compound bow. In contrast to other bows, this results in a non-linear force curve when pulling out: With increasing pull, the force initially increases steadily (as with other bows), but then suddenly decreases when the so-called summit pulling weight is exceeded. When the bow is fully extended, the archer only holds a fraction of the weight of the summit pull in his hand. The draft reduction can be up to 80%, i. H. with a 50 pound summit pull, the shooter only needs to hold ten pounds in the extension. This means that the bow can be held more steadily and aiming is much easier.

The compound bow is the most modern of all bows and is usually shot with a mechanical release aid (the "release"; English to release sth. = To notch something, to release something) in order to reduce drainage errors. In addition, spirit levels and magnifications are used in the visor. Coupled with the low weight, these aids make the compound bow very precise overall. In 2012 z. B. the world record in the FITA round (men) outdoors with 144 arrows and 1419 rings in the compound. In comparison, the world record FITA round (men) in the open air with 144 arrows and 1387 rings with the recurve.

Yumi

The Japanese bow (yumi) still used today in kyūdō is an asymmetrical composite bow. The arrow is led to the shot on the right side of the bow, as it was also common among Asian horsemen. In early history, however, there are also depictions of symmetrical arches and earlier forms made of solid material.

crossbow

The crossbow, historically also known as a crossbow , is a bow mounted horizontally on a central column, the string of which can be held in a cocked position by a retaining device and released for the shot using a trigger mechanism.

Construction methods and materials

Composite arches

A composite bow is a special bow made of several different materials that was created in Central Asia at the end of the Neolithic Age. The oldest archaeological finds come from the Pribaikalja region , northwest of Lake Baikal in southern Siberia. The 16 arches found there in a burial ground have been stiffened with strips of antler on the belly side and end in pointed tips.

Reflex bows are usually made of composite construction. The use of composite arches spread from the steppes in the Bronze Age Mediterranean and Chinese cultures. For the production of composite bows, different layers of wood and animal horn were glued together and given a sinew coating in a complex process that took up to two years . The function of the wood was limited z. T. on the mere wearing of animal materials. The result was a weapon that was smaller than traditional bows but still had a high clamping force and was ideal for riders. Animal tendons have about four times the tensile strength of wood. Horn can withstand twice as much pressure as wood. Therefore, when building arches, the required layer thickness can be reduced to a quarter or half compared to wood. Thinner bow arms are more elastic than thicker ones; However, the less energy is lost when bending the limbs, the more can be released when the arrow is fired. Smaller and shorter limbs also have less mass that has to be moved. In addition, composite materials can be glued together in a technically particularly effective design.

The advantage of tendons and horns is their greater ability to store energy and also to give it back to the arrow . The efficiency of such a well-built composite bow with the corresponding possible shape is higher than that of a conventional bow made of wood, which would break immediately if the layout was identical. Mongolian and Turkish equestrian bows had an average draw weight of 75 pounds and shot specially tuned light arrows 500 to 800 meters.

The best known were the Huns and, a few hundred years later, the Mongols and Turks , whose movements to the west the peoples of Europe initially had little to oppose. Their military advantage was based on the massive use of the light cavalry, which - armed with composite bows - could carry out mobile and far-reaching attacks on the enemy. However, composite bows have been adopted by settled peoples, including the Romans and Parthians, since ancient times . The Arcus was one of the composite bows used by the Greeks and later by the Romans.

The disadvantage of such classic composite bows is that they are very susceptible to any type of moisture - in extreme cases, the composite material held together by elastic and high-strength hide glue simply dissolves, causing the sheet to be irreparably destroyed. This problem probably influenced the Huns' withdrawal around the year 500, which was decisive for the fate of Europe.

Another example of the effective use of composite bows is found in the Comanche of North America, recognized by the hostile armies of the young United States in the 19th century as the "best light cavalry in the world."

The Turks were relatively advanced in the history of bow making. Very beautiful specimens are exhibited in the Völkerkundemuseum in Vienna and in the castle in Karlsruhe in the weapons collections of the spoils of war from the last Turkish siege (see Karlsruhe Turks' booty ). It is particularly important to ensure that the ends of the arches are bent forward when they are not tensioned. When the bowstring is strung, it is usually heated and bent in the opposite direction so that only then the final shape of the bow becomes visible.

Modern fiber composite materials shape today's types of recurve and compound bows .

Backings

A backing ( English : reinforcement of the arch back, meaning the front of the arch, on the belly side is the tendon), also called lamination (coating), is a bamboo or other wood cut into strips that can withstand tensile loads. Tendons from large animals or animal rawhide are glued to the front of a bow in order to absorb the heavy tensile load. The most effective form of a backing is the tendon covering . Depending on the type of wood, the backing must be thicker or thinner so that the wooden part of the arch does not suffer compression breaks. In the case of yew, this is actually not required, since the sapwood (outside) of the yew has excellent tensile strength, while the heartwood (inside) can withstand high pressure. The sapwood can stretch very well and the heartwood compresses well.

Steel arches

The susceptibility of composite arches to moisture led to the development of steel arches in India . The Indian blacksmiths had the metallurgical knowledge to produce suitable alloys. In Agni Purana , an Indian religious text from the 9th century, arches made of metal are already mentioned.

The bows were not as powerful as conventional composite bows, but they were more durable and otherwise more resistant in a humid climate. Steel arches could also be stored without any problems. Steel arches used by aristocratic warriors were richly decorated.

In Europe, steel bows were only made for crossbows .

Archery as a sport

There are different disciplines in modern archery. In general, bows without sighting aids and stabilization weights are referred to as bare bows (“barebow”). Modern long and hunting recurve bows are laminated from different layers made of wood or plastic reinforced with glass or carbon fibers. Recurve sports bows made of aluminum and carbon fiber reinforced plastic are also bare bows if neither the bow nor the tendon has aids for sighting, distance estimation or stabilization. In modern sports bows, a distinction is therefore made between bare bows (recurve without visor and stabilization aid), Olympic recurve sports bow (visor and stabilization aid permitted) and compound bow (visor with lens optics and stabilization aid permitted).

Mounted archery was and is practiced as a sport in various cultures .

The motto of the archers is: "All into the gold", or "All into the kill" for the 3D archers .

Bow hunting and fishing

Bow hunting is the practice of hunting with a bow and arrow . As one of the oldest forms of human hunting, it is still practiced today by indigenous peoples to obtain food. Modern bow hunting is now permitted in 18 European countries and large parts of the world. In addition to procuring food, it also serves as a means of controlling wild animal populations in protected areas and in urban areas .

In Europe bow hunting can only be carried out by trained hunters with a hunting license who also have a bow hunting license. Hunting compound bows are preferred , as they have the necessary hunting precision and penetration power to hunt even strong game. Apart from the bows of primitive peoples, long or recurve bows are nowadays only rarely used in modern bow hunting. They are particularly useful when hunting birds and small game. The intuitive shot is best suited for this type of hunt; these bow types without sights are particularly advantageous.

Performance, range

Arches made from natural products :

- The Turkish Sultan Selim III. is said to have shot an arrow 889 m far in 1798. This would be the greatest distance so far for a bow made from natural materials.

- English longbow, draw weight 90.72 kg, 57 g wooden arrow, firing range 427 m (John Huffer, USA, September 11, 1997)

The following widths were achieved with modern arches:

- Recurve (1987, Don Brown, USA): 1222.0 m

- Compound (1992, K. Strother, USA): 1207.4 m

- Foot arch shooting method (Harry Drake, USA, September 24, 1971): 1854.4 m. With this method of shooting, the shooter lies on the ground. The bow is pushed forward with both feet and the tendon is tightened with both hands at the same time.

Legal situation in Germany

The bow is a weapon. However, it does not fall under the restrictions of the Weapons Act or the Weapons Ordinance and can be used as sports equipment without further permission.

The legal situation is regulated by the Weapons Act (WaffG). Sections 1 and 2 of the Weapons Act and the associated appendices are decisive for the assessment . Basically, the bow is a weapon according to § 1 WaffG. Appendix 1 to the Weapons Act (to Paragraph 1, Paragraph 4 of the Weapons Act) defines in Section 1, Subsection 2, Number 2 as objects that are equivalent to firearms with "... in which solid bodies are targeted and whose drive energy is introduced by muscle power ..." , what as far as would include the bow. However, then follows the restriction “... and can be saved by a locking device.” Thus, number 1.2.2 of Appendix 1 applies to crossbows, but not to bows. In no other place in Appendix 1 is the form mentioned or a corresponding definition used. The situation then becomes clear with Annex 2 to the Weapons Act (to Paragraph 2, Paragraphs 2 to 4 of the Weapons Act). The list of weapons in Annex 2 in Section 3, Subsection 2, Number 2, partially excludes firearms from the law "... in which solid bodies are driven by muscle power without the possibility of storing the drive energy introduced in this way by a locking device." (Including bows). The partial exception relates to apparent weapons according to Section 42a WaffG. The bow is therefore not a weapon for which the provisions of the WaffG apply.

For this reason, archery ranges do not constitute shooting ranges that require a license, and their operation does not require a permit under weapons law to operate a shooting range in accordance with Section 27 (1) WaffG. However, arcs can be dangerous. In the case of archery areas in the open air, in particular, if the shooting is not carried out properly, there is a possibility that people or property and thus public safety are endangered by the arrows fired. The guarantee of public safety is assigned to different authorities depending on national law .

The German Field Bow Sports Association and the German Schützenbund have published the "Safety and Construction Rules for Archery Fields" to ensure public safety and the safe implementation of archery . It contains explanations of the structural design of archery lanes and field courses, defines hazard, safety and harmless areas and specifies behavior. The safety and construction rules represent state-of-the-art safety rules. The German Archery Association also applies these rules. The archery associations recommend that you consult the responsible authorities when setting up archery areas.

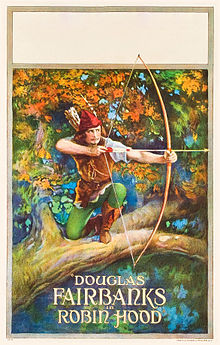

photos

Egyptian chariot driver and typical angular bow

Hercules kills the Nemean lion (his bow hangs on the tree on the right)

Death as an archer with three arrows shot at the same time (from the dance of death "Danse Macabre" Commons)

Diana on the hunt

Apollo and Diana

literature

- Jürgen Junkmanns: Bow and Arrow - From the Paleolithic to the Middle Ages. Verlag Angelika Hörnig , Ludwigshafen 2013, ISBN 978-3-938921-27-2 .

- Peter O. Stecher: Legends in Archery: Adventurers with Bow and Arrow. Schiffer Pub Co, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7643-3575-4 . (English)

- Manfred Korfmann : Slingshot and bow in Southwest Asia: from the earliest records to the beginning of the historic city-states. Antiquitas: Series 3, treatises on prehistory and early history, on classical and provincial Roman archeology and on the history of antiquity, vol. 13. Habelt, Frankfurt 1972, ISBN 3-7749-1227-0 .

- Ulrich Stodiek, Harm Paulsen: "With the arrow, the bow ..." Techniques of Stone Age hunting. Isensee, Oldenburg 1996, ISBN 3-89598-388-8 .

- Thomas Marcotty: Bow and Arrows (Edition Arcofact). Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2002, ISBN 3-9805877-8-9 .

- Roger Ascham, Hendrik Wiethase (ed.): Toxophilus - The school of archery. Wiethase, Untergriesbach 2005, ISBN 3-937632-12-3 (England, 1545).

- Śārṅgadhara, Hendrik Wiethase (Ed.): Dhanurveda - The knowledge of the bow. Wiethase, Untergriesbach 2005, ISBN 3-937632-14-X (India, 16th century).

- Richard Kinseher: The bow in culture, music and medicine, as a tool and weapon. Kinseher, Kelheim 2005, ISBN 3-8311-4109-6 .

- Holger Riesch: "Quod nullus in hostem habeat baculum sed arcum". Bow and arrow as an example of technological innovations of the Carolingian era . In: Technikgeschichte, Vol. 61 (1994), H. 3, pp. 209-226.

- Bow making

- Flemming Alrune et al. a .: The bow maker book. European bow making from the Stone Age to today. 7th edition. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2012, ISBN 978-3-9805877-7-8 .

- Steve Allely: The Bible of Traditional Bow Making . Vol. 1. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2003, ISBN 3-9808743-2-X .

- G. Fred Asbell: The Bible of Traditional Bow Making . Vol. 2. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2004, ISBN 3-9808743-5-4 (contains chapters on composite bows )

- Tim Baker: The Bible of Traditional Bow Making. Vol. 3. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2005, ISBN 3-9808743-9-7 .

- Steve Allely et al. a .: The Bible of traditional bow making. Vol. 4. 2nd edition. Verlag Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2008, ISBN 978-3-938921-07-4 .

Web links

- Arch efficiency (PDF; 440 kB)

- Dissertation "Wound ballistics for arrow injuries" - with extensive presentation of the basics of archery (PDF; 2.75 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See rock paintings in the Spanish Levant

- ↑ Marlize Lombard, Laurel Phillipson: Indications of bow and stone-tipped arrow use 64,000 years ago in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa . In: Antiquity . 84, No. 325, 2015, ISSN 0003-598X , pp. 635-648. doi : 10.1017 / S0003598X00100134 .

- ↑ L. Pericot Garcia: La cueva del Parpallo. Madrid 1957.

- ↑ Ulrich Stodiek, Harm Paulsen: With the arrow, the bow. Oldenburg (Isensee-Verlag), 1996, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ a b Gaëlle Rosendahl, Karl-Wilhelm Beinhauer, Manfred Löscher, Kurt Kreipl, Rudolf Walter, Wilfried Rosendahl: Le plus vieil arc du monde? Une pièce intéressante en provenance de Mannheim, Allemagne . In: L'Anthropologie . 110, No. 3, 2006, ISSN 0003-5521 , pp. 371-382. doi : 10.1016 / j.anthro.2006.06.008 .

- ↑ calibrated with CalPal online (accessed on January 18, 2014)

- ^ Henri Breuil : Une visite à la grotte des Fadets à Lussac-le-Châteaux (Vienne). Bulletin AFAS Paris, 1905, p. 358.

- ↑ Jean Airvaux, André Chollet: Figuration humaine sur plaquette à la grotto of Fadets à Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne) . Bulletin Societe Prehistoire Francaise 82 (1985), pp. 83-85.

- ↑ G. Burov: The arch among the Mesolithic tribes of Northeast Europe. Publications of the Museum of Prehistory and Early History Potsdam 14/15, 1980, pp. 373–388. CA Bergman: The Development of the Bow in Western Europe: A Technological and Functional Perspective. In: GL Peterkin, HM Bricker, P. Mellars (Eds.): Hunting and Animal Exploitation in the Later Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Eurasia. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 4 (1993). Pp. 95-105.

- ↑ Leif Steguweit: Bow Traps - From the bag of tricks of the Stone Age. In: Traditional archery 21, 2001, pp. 21–24. ( PDF download )

- ↑ Eva-Maria Mertens, linden, elm, hazel. For the use of plants for hunting and fishing equipment in the Mesolithic in Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. Prehistoric Journal 75/1, 2000, Fig. 3.

- ↑ Eva-Maria Mertens, linden, elm, hazel. For the use of plants for hunting and fishing equipment in the Mesolithic in Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. Prehistoric Journal 75/1, 2000, Tab. 1.

- ↑ M.-S. Hernández Pérez, P. Ferrer Marset, E. Catalá Ferrer: Arte rupestre en Alicante. Alicante (Center d'Estudis Contestans), 1988.

- ↑ a b Leif Steguweit documents for recurve bows in the European Neolithic. In: Volker Alles (Ed.): Reflexbogen. History and manufacture . Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2009, pp. 10–25.

- ^ Holger Eckhardt: bow and arrow. An archaeological-technological investigation of the Urnenfeld and Hallstatt period findings. International archeology. Vol. 21. Marie Leidorf, Espelkamp 1996, ISBN 3-924734-39-9 ; b: Cat.-No. 211-212

- ^ Paul Comstock: Arch of European prehistory. In: The Bible of Traditional Bow Making . Vol. 2. Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2004, ISBN 3-9808743-5-4 , pp. 110-111.

- ↑ Holger Riesch: Bow and arrow in the Merovingian era. A source study and reconstruction of early medieval archery. Karfunkel, Wald-Michelbach, 2002.

- ^ Longbow in the English language Wikipedia

- ↑ WF Paterson: Encyclopaedia of archery . St. Martin's Press, New York 1984, ISBN 0-312-24585-8 , pp. 37 .

- ^ Ernest Gerald Heath: Archery: the modern approach . 2nd Edition. Faber and Faber, London 1978, ISBN 978-0-571-04957-8 , pp. 14-16 .

- ↑ Pronunciation recurve

- ↑ Der Brockhaus multimedial 2010, article arch : "The assembled arch is usually constructed in such a way that the ends of the arch (also referred to as 'arch arms') bend towards the target in a relaxed state (reflex arch)."

- ↑ Volker Alles (Ed.): Reflexbogen. History and manufacture. Angelika Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2009, pp. 10–25.

- ↑ Dwight R. Schuh: Bowhunting Equipment & Skills , published by Creative Publishing Int'l, 1997, ISBN 1-61060-306-0 , page 28 .

- ↑ http://www.archery.org/

- ^ Charles E. Grayson, Daniel S. Glover: Bows, Arrows, Quivers from Six Continents: the Charles E. Grayson Collection . Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2010, ISBN 978-3-938921-17-3 , pp. 193 f .

- ↑ Angelika O'Sullivan: Weapon designations in Old High German glosses: Linguistic and cultural historical analyzes and dictionary (= Lingua Historica Germanica . Volume 5 ). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-05-006434-5 , p. 41 .

- ↑ AP Okladnikov: Neolit i Bronsovij vek Pribaikalja. Materialij i isledovania po archeologij SSSR 18. Moscow / Leningrad 1950.

- ^ G. Rausing: The Bow: Some Notes on its Origin and Development. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia 6. CWK Gleerups, Lund 1967, pp. 119-121.

- ^ Brian Lovett (eds.): Deer & Deer Hunting's Guide to Better Bow-Hunting . Krause Publications, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4402-3092-9 , chap. 29 .

- ^ Nations. Accessed February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Foot arch record shot over a mile in the picture

- ↑ List of records of the United States National Archery Association

- ↑ Safety and construction rules for archery areas. (pdf; 2.9 MB) Deutscher Feldbogen Sportverband and Deutscher Schützenbund, March 21, 2009, accessed on February 14, 2020 .

![{\ displaystyle {\ text {Virtual mass of the arch:}} \ qquad M_ {v} = {\ frac {m_ {2} v_ {2} ^ {2} -m_ {1} v_ {1} ^ {2} } {v_ {1} ^ {2} -v_ {2} ^ {2}}} \ quad \ left [{\ text {kg}} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acbecb0c82a970d8f66fbd0ecb3ca2d1e32cf737)

![{\ displaystyle {\ text {blank shot:}} \ qquad v_ {0} = v_ {a} \ cdot {\ sqrt {1 + {\ frac {m_ {a}} {M_ {v}}}}} \ quad \ left [{\ frac {\ text {m}} {\ text {s}}} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9d695c90d927c76ad0dc1c6e0e728e6fa2ad01b)

![{\ displaystyle {\ text {Arrow speed:}} \ qquad v_ {x} = v_ {0} \ cdot {\ sqrt {\ left (1 + {\ frac {m _ {\ text {arrow}}} {M_ {v }}} \ right) ^ {- 1}}} \ quad \ left [{\ frac {\ text {m}} {\ text {s}}} \ right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/10a003cc74320aa48677d01f14d499d4387a68d6)