Upton Sinclair

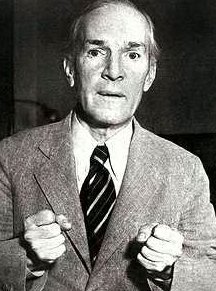

Upton Beall Sinclair (born September 20, 1878 in Baltimore , Maryland , † November 25, 1968 in Bound Brook , New Jersey ) was an American writer. His work spans various literary genres and addresses social criticism in many forms. At the beginning of the 20th century in particular, it enjoyed great popularity in the United States, but also in German-speaking countries. From 1915 he lived in Pasadena , California , then in Buckeye , Arizona . He was married three times in total. Sinclair became known in Germany through numerous translations.

Youth and education

Sinclair grew up under unusual circumstances: his father was an alcoholic and everyday life was marked by bitter poverty. With his grandparents in New York , Sinclair got to know the life of wealthy Americans. This is how he encountered the two extreme positions of American society early on.

To finance his studies at New York City College , he wrote jokes , dime novels , and short stories for magazines and newspapers. He was so successful with it that he was able to study at the renowned Columbia University .

“The Jungle” as a breakthrough

His revelatory novel The Jungle (German title initially The Swamp , later: The Jungle ), which dealt with the working and hygiene conditions in the US canned meat industry in Chicago's Union Stock Yards , was first published in February 1905 in the socialist magazine Appeal to Reason released. At the same time, Sinclair tried to get it published as a book. Several publishers rejected the book or asked him to let out "blood and guts", that is to say, to cut the work by explosive passages, which he refused. The publisher Doubleday, Page & Company published the novel at the end of February 1906 after the circumstances described in it had been checked for accuracy.

The book became an instant bestseller and made Sinclair known across the country in one fell swoop - the realistic details of the conditions in the slaughterhouses got through the press, translations of the book in 17 languages appeared within a few months. The general stir among the public led to the enforcement of a special law on the inspection of slaughterhouses in order to maintain the hygiene and the wage level. However, this only temporarily improved working conditions.

Sinclair was disappointed with the reception. He had hoped to reach people's hearts, but had only reached their stomachs: “I was much less interested in the 'damn meat' than I was in something completely different, the inferno of exploitation. [...] I realized that [...] the public didn't care about the workers, they just didn't want to eat tuberculosis-contaminated beef. "

In 1914, Sinclair worked on the filming of his novel.

Social policy ambitions

After he published The Jungle , he invested about $ 30,000 of his wages in the Helicon Home Colony , a utopian commune in New Jersey. However, this burned down just four months later.

Theodore Roosevelt coined for him and other socially critical authors the dirty name Muckraker (= dirt agitator, nest dirtier), but this did not prevent him from using Sinclair's arguments if they could serve his own reform course. The term muckraking is still used today in everyday American language for socially critical literature and investigative journalism .

Sinclair ran for political posts several times, for example in 1906 and 1920 as a member of the Socialist Party for the House of Representatives and in 1922 for the Senate . In 1926 and 1930 he appeared as a socialist with no chance of success in the gubernatorial election in California. Together with his second wife, Mary Craig, he financed Sergei Eisenstein's film ¡Qué viva México! In 1930/31 . .

In 1934, Sinclair switched to the Democratic Party and won their nomination for the governor of California . His election manifesto included a social plan known as EPIC ( End Poverty in California ). Nevertheless, he was defeated by the Republican incumbent Frank Merriam with 38:49 percent of the vote.

For Sinclair, the criticism of social grievances was at the center of his literary work. His rank as a journalist and social reformer remained undisputed. It found its greatest recognition - with the exception of the short time when it was also popular in the USA thanks to The Jungle - in Europe . He was widely read on the German-speaking left, and his figure of the well-behaved, disciplined party activist Jimmie Higgins at times became proverbial.

The Brass Check

Due to his political position, however, Sinclair had to publish some of his dramas , novels , children's books and political-sociological studies in the United States himself because no publisher was willing to print and market his books. The works he published were not discussed in the press of his time. These included, for example, The Brass Check (1919) (German translation: Der Sündenlohn. A study on journalism , 1921), a study in which Sinclair outlined the limitations of the press, including the manipulation techniques of William Randolph Hearst's rainbow press . Sinclair called this work "the most important and dangerous book I have ever written".

Press critics of his time and present found Sinclair's analysis of the media to be accurate and valuable. It was “muckraking at its best” and “amazingly clairvoyant in its criticism of the comfortableness of the interests of big media and other corporations.” After it was published, “most newspapers refused to review the book, and the few that did it found it it unsympathetic. Many newspapers, such as the New York Times, even refused to run paid advertisements for the book. ”“ The historians who bothered to consider Brass Check dismiss it as short-lived and state that the problems presented have been solved been. "

Quote

- The cinema unites and unifies the world. That means: he Americanizes them. (Sinclair 1917)

Honors

It was not until 1943 that Sinclair was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Dragon's Teeth , the third novel in a multi-volume series that takes the hero Lanny Budd adventurously through contemporary events from 1913 to 1949. In 1944 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

Albert Einstein dedicated the following lines to him: Who does the dirtiest pot not challenge? / Who pats the world on the hollow tooth? / Who despises what is today / and swears by tomorrow? / ... The Sinclair is the brave man / If one, then I can testify! In 1937 he wrote him the poem: Can't you control your courage to fight? / Is it all about beating up an old girl? / Stop, my friend, there are far more serious goals / Where heroism is necessary in the turmoil! From the early 1930s to the mid-1950s, the two had written each other many letters that were stored in the Einstein archive.

Works (selection)

- Under the pseudonym Ensign Clarke Fitch: Clif, the Naval Cadet, Or Exciting Days at Annapolis. David McKay, Philadelphia 1903. (English)

- same pseudonym: Clif Faraday In Command or The Fight of His Life. In: True Blue. Striking Stories of Naval Academy Life. Street & Smith Publ., NY 1899, Journal, Nro. 39, February 4, 1899

- same pseudonym: Strange Cruise Or Cliff Faraday's Yacht Chase. Series: Annapolis Series Vol. 5, ibid. 1903

- Springtime and Harvest. (1901); first novella, (German King Midas 1922);

- The jungle. Doubleday, Page & Co., New York 1906, (Eng. The Swamp ). Translation Hermynia Zur Mühlen , A. Sponholtz Verlag, Hanover 1922, new arrangement by Upton Sinclair and new translation by Zur Mühlen, Malik Verlag 1923, new translation by Ingeborg Gronke as Der Dschungel . Construction Verlag, Berlin 1974.

- The Cry for Justice. (1915) (German EA Sklaverei, translation Hermynia Zur Mühlen, Interterritorialer Verlag Renaissance (Erdtracht), Vienna / Berlin / Leipzig / New York 1923 and C. F. Fleicher, Leipzig 1923)

- King Coal. (1917). German King Coal . Introduction Georg Brandes , Internationaler Verlag, Zurich 1918.

- The Profits of Religion. (1918). Dt religion and profit . Der Neue Geist Verlag, Leipzig 1922. ( Essays )

- Jimmie Higgins. (1919) (German EA Jimmie Higgins , Kiepenheuer Potsdam 1919)

- The Brass Check. (1920); Criticism of journalism (German: the sin wage 1921, abridged)

- The Book of Life, Mind and Body. (German: The Book of Life 1920); Printed in 1922 (3 volumes: 1-book of the spirit, 2-book of the body & love, 3-book of society)

- The House of Wonder. In: Pearson's Magazine , June 1922. (Eng. The House of Miracles: a report on Dr. Albert Abrams' revolutionary discovery: the establishment of the diagnosis by means of the radioactivity of the blood , transferred by Hermynia Zur Mühlen. Orbis-Verlag, Prague 1922)

- The Goosestep. (1923); Social criticism at the higher educational institutions

-

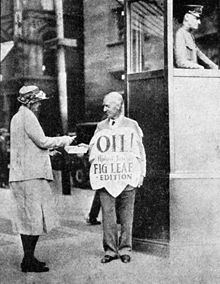

Oil! (1927) (dt. EA Petroleum ), Malik-Verlag, Berlin 1927 (with the fig leaf ribbon bookmark "The moral reader is left at home ...). Based on the novel for the film There Will Be Blood with Daniel Day-Lewis , (2007 )

- German by Andrea Ott (2013): Oil! , with an afterword by Ilya Trojanow . Manesse Verlag, Munich, ISBN 978-3-7175-2254-6 .

- Money Writes! (1927); (Eng. The Money Writes. A Study of American Literature , 1930)

- Boston. (1928) (Ger. EA Boston, The story of Sacco and Vanzetti . Malik-Verlag, Berlin 1929). Newly translated by Viola Siegemund, Manesse-Verlag, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7175-2380-2

- The Wet Parade. (1932) (German EA alcohol , translation by Elias Canetti , Malik-Verlag , Berlin 1932)

- CO-OP. (1936) (German EA CO-OP , Verlag Friedrich Oetinger Hamburg 1948).

- The Gnomobile. A Gnice Gnew Gnarrative With Gnonsense But Gnothing Gnaughty. (1936) (German The Gnomobile 1964)

- The Flivver King. 1937. The German translations with different titles: Autokönig Ford (1938); The Assembly Line (1948); Assembly line. A novel from FORD America. (1974); On the assembly line. Mr. Ford and his servant Shutt (1983 March; 1985 ff. Rowohlt; again in 2004 Area, Erftstadt as double volume with jungle ) For text see web links

- Dear comrade, the Maliks have decided ... , Wieland Herzfelde , Hermynia zur Mühlen , Upton Sinclair, letters 1919–1950, Bonn 2001

- Lanny Budd cycle:

- World's End. (1940) (German world end 1942)

- Between Two Worlds. (1941) (German Between Two Worlds 1947)

- Dragon's Teeth. (1942) (German dragon teeth 1946)

- Wide is the gate. (1943) (The gate is wide in 1947)

- Presidential agent. (1944) (German agent of the President 1948)

- Dragon Harvest. (1945) (German Devil's Harvest 1949)

- A world to win. (1946) (German fate in the east 1950)

- Presidential Mission. (1947) (German commissioned by the President 1951)

- One Clear Call. (1948) (German The Eleventh Hour 1952)

- O shepherd, speak. (1949) (Ger. O Schäfer, speak 1953)

- CoOp. 1936 (German EA CoOp 1948, Verlag Friedrich Oetinger)

- The Return of Lanny Budd. (1953) (German Lanny Budd returns 1953)

- What Didymus Did. (1954) (German The Miracles of Didymus 1955)

- Mountain City. (1930) (German: How to make dollars in 1931). Malik publishing house, Berlin

- Affectionately, Eve. (1961) (German Eva discovers paradise . Translation Dorothea Gotfurt , 1962)

literature

- Edmund Schulz: Upton Sinclair. Bibliography of his works in German. Book editions, dependent publications, journalism Schöneworth (Interdruck), Hannover 2007 ISBN 978-3-9811060-0-8

- ders .: US in the German-language press. A bibliography self-published, Leipzig 2006 (In the appendix: Unprinted university papers on US (5 titles))

- ders .: Bibliography of the German-language book editions U. S's. ibid. 1996 (forerunner to: ders. 2007)

- Dieter Herms: Upton Sinclair, American radical. An introduction to life and work in March, Jossa 1978. (Extensive literature catalog in English with approx. 50 titles; index)

- ders .: US between pop, second culture and ruling ideology argument, Berlin 1986 ISBN 3-88619-765-4

- ders .: Afterwords in most editions of the Dschungel , which are based on the MARCH edition (transl. Otto Wilck) (since 1980)

- ders .: Forgotten rebels? US: Spanish Civil War Argument, Berlin 1989 (Series: Gulliver, Vol. 25)

- Gerhard Pohl: US - Man and the work in: US: President of the USA Universum, Berlin 1927 (series: Univ.-Bücherei für alle); again: Robinson-Verlag Berlin 1928

- Ursula Zänsler: On the social function of muckraking in the US s university dissertation Diss. A., pedagogue. Potsdam University of Applied Sciences, 1982

- Franz-Peter Spaunhorst: Literary cultural criticism as a decoding of power and values using the example of selected novels by US, Frank Norris , John Dos Passos and Sinclair Lewis . A contribution to the theory and method of American studies as cultural studies Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1987 (Series: Europäische Hochschulschriften, R. 14: Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature, Vol. 167) Zugl .: Bielefeld University, Diss., 1986. ISBN 3-8204- 9742-0

- Utz Riese & Doris Dziwas: US in American Modernism. In: Zs. Weimar contributions. Journal for literary studies, aesthetics and cultural theory. 36th year 1990, H. 6. pp. 885-909. Construction, Berlin

- Floyd Dell : Upton Sinclair: A Study in Social Protest. Essay, 1927

- Kevin Mattson: Upton Sinclair and the other American century. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ 2006, ISBN 978-0-471-72511-4

Web links

- Literature by and about Upton Sinclair in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Upton Sinclair in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Upton Sinclair in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- WSWS on Upton Sinclair's 1934 election campaign

- Upton Sinclair's work in German, bibliography

- e-texts on the net

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the largely uncritical reception of Sinclair and also of Frank Norris : Matthias Uecker: Reality and Literature: Strategies of Documentary Writing in the Weimar Republic . Peter Lang Verlag, Oxford / Berlin 2007, p. 75.

- ↑ The Great Slaughter: Upton Sinclair's "The Jungle". Retrieved November 25, 2017 .

- ↑ Mark Sullivan: Our Times . New York: Scribner, 1996; P. 222f. ISBN 0-684-81573-7 .

- ^ The Stalin-Kaganovich Correspondence, 1931-1936, page 82

- ↑ Our Campaigns: Upton Sinclair

- ↑ Steve Trott: Upton Sinclair & The Jungle . The centenary of an anti-capitalist classic. In: Socialist standard . No. 1227 . World socialism, November 2006 (English, worldsocialism.org ).

- ↑ Hicks, Granville. The Survival of Upton Sinclair. In: College English 4: 4 (January, 1943), pp. 213-220.

- ↑ Klein, Julia M. Sinclair Redux. In: Columbia Journalism Review . 45: 2 (Jul / Aug 2006), pp. 58-61.

- ^ Robert W. McChesney, Ben Scott: Upton Sinclair and the contradictions of capitalist journalism. In: Monthly Review 54.1 (May 2002), pp. 1-14. "[M] ost newspapers refused to review the book, and those very few that did were almost always unsympathetic. Many newspapers, like the "New York Times", even refused to run paid advertisements for the book. "

- ^ Robert W. McChesney, Ben Scott: U pton Sinclair and the contradictions of capitalist journalism. In: Monthly Review 54.1 (May 2002), pp. 1-14. "..Those historians who bother to mention The Brass Check dismiss it as ephemeral, explaining that the problems it depicts have been solved."

- ^ Members: Upton Sinclair. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed April 26, 2019 .

- ↑ archive no. 31-121-1, handwritten draft 1933 ; Einstein Archives Online, Hebrew University of Jerusalem / California Institute of Technology / Princeton University Press, accessed November 28, 2015.

- ↑ archive no. 31-190-1, handwritten on April 29, 1937 ; Einstein Archives Online, Hebrew University of Jerusalem / California Institute of Technology / Princeton University Press, accessed November 28, 2015.

- ↑ Subtitle in the March issue of Zweiausendeins 1978, inside title

- ↑ The Rowohlt TB edition with the misspelled name ... Shutt . - Louis-Ferdinand Céline had already treated Ford's assembly line in Detroit in 1932 in Voyage au bout de la nuit, German adaptation 1933, German translation 2003

- ^ Review of Manfred George in Aufbau 1940. No. 38, p. 17 f., Readable online. "With a side note about a type of Jew"

- ↑ as note to World's end, but 1943, No. 11, p. 15, Hans Lamm

- ↑ as note to World's end, but 1944, No. 23, p. 26

- ↑ as note to World's end, but 1945, No. 25, p. 11

- ↑ as note to World's end, but 1946, No. 33, p. 6, Ralph M. Nunberg = RN "Again Lanny Budd"

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sinclair, Upton |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fitch, Ensign Clarke (pseudonym); Sinclair, Upton Beall (legal name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 20, 1878 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Baltimore , Maryland |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 25, 1968 |

| Place of death | Bound Brook , New Jersey |