Disaster at the Djatlov Pass

Coordinates: 61 ° 45 ′ 15 ″ N , 59 ° 26 ′ 42 ″ E

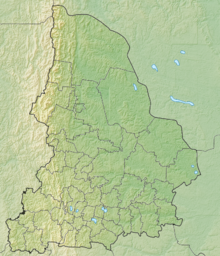

Location of Mount Cholat Syachl in Russia, where the accident occurred in 1959. |

The unexplained death of nine ski hikers in the northern Urals in the Soviet Union , in the area between the Komi Republic and the Sverdlovsk Oblast in 1959, is described as the accident at the Dyatlov Pass ( Russian: Гибель тургруппы Дятлова ) . They died in the night of February 1 to February 2, 1959 on the northeastern slope of Mount Cholat Sjachl ( Mansi for mountain of death ; 1097 m ). The mountain pass where the accident happened was later named after the group leader Igor Dyatlov Dyatlov Pass .

The lack of eyewitnesses, the circumstances of the accident and subsequent journalistic investigations into the death of the hikers sparked much speculation. Investigations into the deaths came to the conclusion that the hikers likely slit open their tent from the inside and left it barefoot and lightly dressed. The bodies showed no signs of fighting, but two victims had fractured skulls, two broken ribs and internal injuries.

According to the investigation report at the time, the clothes of some of the victims were radioactively contaminated . The Soviet investigative bodies only stipulated that “force majeure” had led to the deaths. Access to the area was blocked for three years after the event. The course of the incident remains unclear as there were no survivors.

The hike

Planned route

The ski tour was organized by the Sports Association of the Urals Polytechnic Institute (UPI for short, Russian Уральский Политехнический Институт, УПИ, today the Ural State Technical University ) on the occasion of the XXI. Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) organized and should last 16 days. On the planned route through the mountains of Northern Urals should the participants at least 350 km on skis and mountain Otorten (Russian Отортен, Height:. 1,235 m , about 13.6 air kilometers from the accident site away) and Ojko-Tschakur be overcome . The route was rated with the highest degree of difficulty (category III).

Attendees

| Participants in the unfortunate hike |

| 1. Igor Djatlov (1937–1959), group leader |

| 2. Yuri Doroshenko (1938–1959) |

| 3. Lyudmila Dubinina (1938–1959) |

| 4. Juri Judin (1937–2013), sole survivor |

| 5. Alexander Kolewatow (1934-1959) |

| 6. Sinaida Kolmogorowa (1937–1959) |

| 7. Georgi Krivonishchenko (1935–1959) |

| 8. Rustem Slobodin (1936-1959) |

| 9. Semyon Solotarev (1921–1959) |

| 10. Nikolai Tibo-Brinjol (1934-1959) |

The group of participants consisted of eight men and two women. All participants were considered to be experienced hikers and, with the exception of Semyon Solotarev, had known each other for several years. When the participants set off, the physical and mental condition of the participants as well as their equipment, some of which was provided by the UPI, seemed to completely meet the requirements of the planned project.

At the time of the accident, 23-year-old Igor Alexeyevich Dyatlov was the leader of the group. The budding engineer studied in the fifth year of his studies at the UPI's Faculty of Radio Technology and participated in the development and construction of VHF radio equipment. Since the beginning of 1959 he has held an assistant position at UPI. He was one of the best athletes in the UPI sports club and had already completed several long tours with various levels of difficulty. Contemporaries described him as a serious, prudent man. The mountain pass where the accident occurred was later named after him.

Yuri Nikolajewitsch Doroshenko, born in 1938, studied like Dyatlov in his fifth year at the UPI's Faculty of Radio Technology. He was considered trained and practiced in long-distance hiking on demanding routes. He and Sinaida Kolmogorova, who also took part in the hike, had been a couple for some time, but had parted on good terms before the expedition began.

Lyudmila Alexandrovna Dubinina, born in 1938, studied civil engineering in her fourth year at the UPI. She had undertaken a hike through the Eastern Sayan in 1957 and in February 1958 led a tour of difficulty level II through the northern Urals. She was accidentally shot by a hunter during the Eastern Sayan tour, but survived the injury. Many of the photographs taken on the Djatlov Pass hike come from her.

Yuri Yefimowitsch Yudin, born in 1937, was a student at the UPI's Faculty of Industrial Engineering, also an experienced hiker and the only survivor of the group.

Alexander Sergejewitsch Kolewatow, born in 1934, studied in the fourth year of his studies at the UPI's Faculty of Physics and Technology. He had previously completed training at the Sverdlovsk School of Mining and Metallurgy and worked from 1953 to 1956 as a laboratory assistant in a secret facility of the Ministry of Medium-sized Mechanical Engineering in Moscow . (The facility later became the “All-Soviet Scientific Research Institute for Inorganic Materials,” which carried out research for the nuclear industry.) Kolewatov also had hiking experience and was known for his accuracy and leadership skills, as well as his methodical approach and conscientiousness.

Sinaida (Sina) Alexejewna Kolmogorowa was born in 1937 and studied in the fifth year of the UPI's Faculty of Radio Technology. She had already undertaken hikes of various difficulty levels in the Altai and Urals and survived the lethal bite of a viper on one of these tours .

UPI graduate Georgi (Yuri) Alexejewitsch Krivonishchenko, born in 1935, was a construction manager at the Mayak nuclear facility (then Combine No. 817) in Chelyabinsk , where he witnessed the Kyshtym accident in September 1957 , in which large amounts of radioactive substances were present were released, which left an Ostural trail of 300 km in length. Krivonishchenko took part in the clean-up work after the accident. He was a friend of Djatlov and had often accompanied him on hikes.

Rustem Wladimirowitsch Slobodin, born in 1936, was also a UPI graduate and worked as an engineer. He too had already taken part in several hikes with varying degrees of difficulty. He was a long-distance runner, boxed and played the mandolin , which he also took with him on the unlucky hike.

Semjon Alexejewitsch Solotarew, known as Sascha, was born in the North Caucasus in 1921 and was the oldest participant in the expedition. He had served in the military from 1941 to 1946 and survived the German-Soviet War . After the war he joined the predecessor party of the CPSU, the Communist All-Union Party (Bolsheviks), and graduated in 1950 from the Institute for Physical Culture (GIFKB) in Minsk . He then worked as a hiking guide in the North Caucasus and Altai. In the summer of 1958 he took up the post of chief hiking guide at the Kourowka hostel in Sverdlovsk Oblast, which he resigned shortly before the unfortunate hike.

Nikolai Wladimirowitsch Tibo-Brinjol had French ancestors, but his family had lived in the Urals for several generations and had produced some well-known civil engineers. During the rule of Stalin , his family was subjected to state repression , as a result of which his mother was sent to an internment camp , where Tibo-Brinjol was born in 1934. After completing his studies at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at UPI in 1958, he worked in Sverdlovsk as a construction manager. Like the other participants, he also had experience with hikes of various difficulty levels.

course

| Chronology of the hike | |

|---|---|

| January 23, 1959 | Gathering of hikers in today's Yekaterinburg. |

| Night from 24./25. January 1959 | Arrival by train in Iwdel. |

| January 26, 1959 | Arrival and overnight in the forest workers' settlement “41. Kwartal ". |

| January 27, 1959 | Arrival at the mining settlement of Wtoroi Severny, where the group will set up camp for the night. |

| Night from 27./28. January 1959 | Yuri Yudin falls ill. |

| January 28, 1959 | Yudin turns back, the rest of the Djatlov group continues the hike along Loswa and Auspija. |

| January 31, 1959 | The group reaches the mountains and sets up camp in the Auspija valley. |

| February 1, 1959 | The group begins by crossing the pass to the Loswatal. The accident occurs halfway through. |

Location of Yekaterinburg, Ivdel and the site of the accident in the Russian Oblast of Sverdlovsk |

The participants met on January 23, 1959 in Sverdlovsk, today's Yekaterinburg , and traveled by train via Serow to Ivdel , the northernmost city in Sverdlovsk Oblast, where they arrived on the night of January 24-25, 1959. On the afternoon of January 26, 1959, they hitchhiked to the forest workers' settlement “41. Kwartal ”and spent the night there in the dormitory of the forest workers. The next day they set out on skis to the abandoned mining settlement of Wtoroi Severny , which once belonged to the Gulag , where they set up camp on January 27-28, 1959. During the night, Judin fell ill so that he had to stop participating in the hike. Black-and-white photographs taken on the morning of January 28, 1959 show how the group said goodbye to him. Judin later testified that up to that point there had been no conflicts or emergencies. He also noticed nothing suspicious.

While Judin returned to the forest workers' settlement, the other participants continued their hike. The group planned to reach Otorten in early February 1959 and arrive at the Wischai settlement no later than February 14, 1959 . They had announced to the UPI that they would contact the UPI via telegram . In the absence of witnesses, the further course of the hike could only be reconstructed using the diaries of the participants found later. (The route plan, usually left with the local ski association, was lost or never submitted by Djatlov.)

From Wtoroi Severny, the group first hiked upriver along the Loswa and then followed the Auspija to the mountains, which they reached on January 31, 1959. Djatlow had initially planned to lead the group on the same day from the Auspijatal over the mountain pass to the Loswatal, where they wanted to spend the night. They began to cross the pass, but then turned back due to strong winds and made their night camp in the Auspija valley at the foot of the Cholat Sjachl. In his last entry in his diary, dated January 31, 1959, Dyatlov wrote: “We are slowly moving away from the Auspija. A gentle climb. The spruce trees are replaced by a sparse birch forest. Then the tree line. Harsh snow . Bare area. We have to find somewhere to sleep. We descend southwards - into the Auspijatal. This is probably the snowiest place. Exhausted, we set up camp for the night. There is little firewood. We make the fire on logs, nobody wants to dig a pit. Dinner in the tent. It's warm here… ”In the Auspijatal, approx. 100 m from the river bank, they built a storage facility for food and equipment, which was intended for the way back.

On the afternoon of February 1, 1959, the group began again to cross the 3.5 kilometer long pass in the direction of Loswatal. After they had made a good half of the distance behind them, they decided to pitch their tent on the northeast slope of Cholat Sjachl. (It is unclear why they did not cover the rest of the relatively short distance into Loswa Valley in order to be able to spend the night there - as originally planned.) The investigative authorities later assumed that the tent was erected after 5:00 p.m. At this time the last photos of the Djatlov group were taken and around 6:00 p.m. the hikers started preparing for the night. Rakitin, however, believes that the hikers set up their last camp around 3:00 p.m. and that the last pictures must have been taken before this time. In his view, the unfortunate events began between 3:30 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. What happened next is still unclear today.

Search and find the bodies

| Chronology of the search | |

|---|---|

| February 20, 1959 | Extraordinary meeting of the sports club and decision to send a search team |

| February 21, 1959 | Start of search |

| February 25, 1959 | Discovery of the ski tracks of the Djatlov group |

| February 26, 1959 | Discovery of the abandoned tent of the Dyatlov group |

| February 27, 1959 | Find the bodies of Doroshenko, Krivonishchenko, Dyatlov and Kolmogorova |

| March 2, 1959 | Discovery of the Dyatlov Group's storage facility |

| March 5, 1959 | Find the body of Slobodin |

| May 4th 1959 | The bodies of Dubinina, Kolewatow, Solotarew and Tibo-Brinjol are found |

Although the group had not arrived in Wischai on February 14, 1959 as announced and had not sent a telegram to the UPI, initially nothing was done, since delays in such expeditions were not uncommon. There had also been reports from other hikers of heavy snowfalls in the area, so there was a possible explanation for the delay. Only after the relatives of the expedition members had requested a search was an extraordinary meeting of the sports club on February 20, 1959, at which it was decided to send out a rescue team. On February 21, 1959, three groups of hiking broke into the search area and on the same day reconnaissance flights were carried out, but they did not provide any information about the whereabouts of the Dyatlov group. In addition, the search of a group of soldiers and students of the NCO School of the Interior Ministry, two foresters, two expert local hunters was Mansi and search dogs support.

From February 23, 1959, three groups of UPI students who had volunteered also took part in the search. The students were brought to the search area by helicopter. One of the groups, led by the student Boris Slobzow and consisting of eleven people, was dropped off at Mount Otorten. On February 25, 1959, the Slobzow group came across the ski tracks of the missing persons in the Auspija valley, approx. 15 km from Otorten. The following day, Slobzow's group split up into three smaller groups in order to pursue the tracks in different directions and to find the Dyatlov group's suspected storage facility nearby. On February 26, 1959, Slobzow and his fellow student Mikhail Sharavin came across the abandoned tent of the Dyatlov group on the slope of Cholat Syachl. After Slobzow and Sharavin had superficially inspected the tent, they returned to the base camp of the Slobzow group due to the deteriorating weather.

On February 27, 1959, the Slobzow group split again into smaller groups to continue the search. Around noon, Sharawin and the student Yuri Koptelowberg discovered a tall conifer on the steep bank of a brook flowing into the Losva, about 1.5 km away from the tent of the Dyatlov group, further down the slope of Cholat Sjachl. Under the tree, next to the remains of an extinguished campfire, they saw the frozen bodies of Doroshenko and Krivonishchenko, covered with a thin layer of snow. While Doroshenko was lying face down on his stomach, Krivonishchenko's body was lying face up on its back. On the same day, other members of the rest of the search team, which had been notified, and Vasily Ivanovich Tempalov, the prosecutor of Iwdel, arrived at the place where the bodies were found. The rescue workers formed a human chain and began to search the slope of Cholat Sjachl with ski sticks and avalanche probes for the remaining seven hikers. In doing so, they first came across Djatlov's body, which was located between the campfire site and the tent that stood further up the slope. The distance from Djatlov's body to the campfire site was estimated at about 400 m. His body was only partially covered by a thin layer of snow and was lying on his back. A few hours later, a search dog found Kolmogorowa, who was lying lifeless under a 10 cm thick blanket of snow. Her body was between Dyatlov's place of discovery and the tent, the distance to Dyatlow being about 500 m.

On March 2, 1959, the apparently untouched store of the Dyatlov group was discovered in the Auspy Valley. Slobodin's body was found on March 5, 1959 - roughly in the middle between the locations of the bodies of Dyatlov and Kolmogorowa. He was lying on his stomach under a layer of snow of 12 to 15 cm. The right arm was bent under the chest, the left was stretched out to the side. The left leg was also stretched out, the right angled towards the upper body. The bodies of Dyatlov, Kolmogorowa and Slobodin were found on an almost straight line between the campfire under the conifer and the tent of the Dyatlov group. Since all three were faced with their heads toward the tent, it was assumed that they were on their way back from the campfire to the tent site.

The search for Dubinina, Kolewatow, Solotarew and Tibo-Brinjol took more than two months. Their bodies were found on May 4, 1959, close together under four meters of snow in a ravine that was to the southwest and about 50 meters from the campfire site. Dubinina's body was dug out of the snow in a kneeling position. She lay with her face and chest on a stone.

The investigations

Traces at the scene of the accident

The following discoveries were made at the scene of the accident:

- The tent entrance faced south. The rear, northern part of the tent was covered by a 15 to 20 cm layer of snow. The lower part of the tent entrance was unbuttoned.

- Immediately next to the tent was an ice ax sticking out of the snow, a pair of skis stuck in the ground, and Djatlow's windbreaker. On the roof of the tent was a working flashlight, which was not covered with snow and which also belonged to Djatlov. Dyatlov's windbreaker contained his passport, the group's train tickets and 710 rubles.

- According to the expert opinion commissioned by the authorities, there were three horizontal sections about 31, 42 and 89 cm in length on the tent wall to the right of the entrance, which had pointed down the slope. On the same side of the tent, near the rear wall of the tent, there was also a long vertical cut that reached to the ridge. According to the report, the cuts were made from the inside. In addition, two large pieces of fabric had been torn from the tent wall.

- A trail of footprints led down the slope to the border of a nearby forest, but after 500 m they were covered by snow.

- Although the temperature was very low (around −25 ° C to −30 ° C) and a strong wind was blowing, the dead were only lightly clothed. Some of the members of the first found group were very scantily clad. Some wore only one shoe while others wore only socks. Some of the four members of the group, discovered later, were wearing rags of clothing that they had cut from the clothing of the first five dead.

- There was no evidence of any other people besides the nine hikers on Cholat Sjachl or in the vicinity.

- Traces at the camp showed that everyone - including those found injured - left the camp on foot independently.

- On the bark of the large conifer, under which there was a small fireplace, traces of skin and muscle tissue were detected up to a height of several meters.

- In the immediate vicinity of the tall coniferous tree under which the bodies of Doroshenko and Krivonishenko were found, there were around a dozen stumps of cut young fir trees.

Autopsy of the bodies

The bodies of Dyatlov, Doroshenko, Kolmogorova and Krivonishchenko were autopsied on March 4, 1959 by two coroners in a mortuary in Ivdel . All four bodies died six to eight hours after the last meal. Yuri Doroshenko had numerous skin abrasions, bruises and bruises, singed hair on the right side of the head and frostbite on his fingers and toes. In the absence of fatal injuries and due to the presence of Wischnewsky spots and hyperemia of the meninges and kidneys, the doctors came to the conclusion that he had died of hypothermia . Georgi Krivonishenko's body was also found to have multiple abrasions, bruises and frostbite on the hands. The lack of the tip of the nose, a swelling and burn injury on the left lower leg, and a piece of skin from the middle finger found in the dead man's mouth were particularly striking. The coroners also found hypothermia as the cause of death. Sinaida Kolmogorowa was diagnosed with cerebral and pulmonary edema as well as multiple skin abrasions all over the face, hands and lumbar region. According to the doctors, the external injuries were caused by falling on a hard surface. They classified her death as a "violent accident". Igor Dyatlov's body also showed numerous abrasions and bruises, but no internal injuries. Due to the presence of Wischnewsky spots, hyperemia of the meninges and other characteristic signs, the coroners assumed hypothermia as the cause of death.

Rustem Slobodin's body was autopsied on March 8, 1959. As for external injuries, he had abrasions and swellings on his face as well as abrasions on his fingers, the right forearm and the left lower leg. The internal examination revealed a 6 cm long and 0.1 cm wide tear on the left temporal bone . The coroner commented, “The cited closed head trauma was caused by a blunt weapon. At the time it was created, it caused Slobodin to become numb for a short time and contributed to his faster freezing. Taking into account the […] mentioned physical injuries, Slobodin was able to move or crawl in the first hours after their infliction […] Slobodin's death occurred as a result of freezing to death. ”The coroner did not describe any external head injury that was to be expected due to the temporal bone tear.

The four corpses from the ravine were examined by forensics on May 9, 1959. Due to the presence of macerations , it was found that they had been in the water for between 6 and 14 days. In the case of Lyudmila Dubinina, the coroner noted, among other things, pulmonary edema, the absence of both eyeballs and the absence of soft tissue on the face and cranium , so that the bones in the yoke , temporal and parietal bones and part of the upper jaw were exposed. The coroner also noted: “The floor of the mouth and the tongue are missing. The upper edge of the hyoid bone is exposed. ”The autopsy file contains no explanation for the absence of the eyeballs, the floor of the mouth and the tongue. No signs of frostbite were found. Instead, the coroner found: "[Dubinina's death] occurred as a result of extensive bleeding in the right ventricle, multiple bilateral rib fractures and massive internal bleeding into the chest cavity [...] The injuries mentioned may have occurred as a result of the application of a great force [... ] with a subsequent fall, prostration or blow to Dubinina's chest. "

In Solotaryov, too, the coroner found missing eyeballs, partially exposed facial bones and acute pulmonary edema. He also had an injury on the back of the head that was 8 cm long and 6 cm wide, exposing the parietal bone. The doctor classified the injury to the back of the head as a symptom of decay. As a cause of death induced by multiple rib fractures was hemothorax determined. Kolewatov's corpse had a knee injury, a head injury that went through to the temporal bone, facial bones exposed in places, a hemothorax and severe signs of decay. As for the cause of death, the coroner said: “His death occurred as a result of exposure to the low temperature. The physical injuries that were discovered on Kolewatov's corpse […] represent posthumous changes. ”Rakitin doubts the cause of death mentioned in the file, since the forensic medical report does not list any reliable signs of a frostbite. As to the cause of death of Tibo-Brinjol, the report states: "[His death] occurred as a result of a closed, impacted multiple-fragment fracture in the area of the skullcap and base , with massive bleeding under the meninges and into the brain substance under the influence of the low ambient temperature." The coroner ruled out the cause of the skull fracture as a fall or falling rocks.

Further circumstances and observations

- After the funerals, relatives of the deceased stated that the victims' skin looked deeply tanned and their hair was completely gray.

- Forensic investigations showed increased doses of radioactive radiation on some victims' clothing.

- A former investigator said in a private interview that his dosimeter on Cholat Sjachl had indicated a high level of radiation . However, the source of the radiation was not found.

- On March 31, 1959, members of the search team saw an apparition in the sky from their camp in Loswa Valley, which they believed to be a UFO . Search team member Valentin Jakimenko described the phenomenon as follows: “Early in the morning it was still dark. Viktor Meshcheryakov, on duty, left the tent and saw a glowing sphere moving across the sky. He woke everyone up. We watched the movement of the sphere (or disk) for twenty minutes until it disappeared behind the mountainside. We saw them facing southeast from the tent. She was moving north. Everyone was upset by this apparition. We were convinced that the death of the Dyatlov group had something to do with it. ”It turned out that similar celestial phenomena had already been seen in the area in February 1959: hikers on Mount Chistop had the“ bright glow of a rocket or one Geschosses ”reported that they had observed near the Otorten on the evening of February 1, 1959 and was followed by a loud, thundering noise. On the morning of February 2, 1959, a similar light was seen from the city of Serov. In addition, in the early morning of February 17, 1959, a group of soldiers from the Inner Troops near Iwdel had seen a “bright white sphere” in the sky, moving from south to north and covered by a cloud of white mist, for about 10 to 15 minutes was wrapped. It was later claimed that the "bullets" were the tail of R-7 ICBMs.

- Some reports speak of a lot of scrap metal found in the area, which in turn has led to speculation that the military has been clandestinely using the area and is now trying to cover up something.

The investigation was terminated in 1959

The investigation was officially closed in May 1959 and the files were archived. The kept secret investigation files led to the suspicion that the authorities might withhold relevant information from the public or conceal something. Copies appeared in the 1990s, but some pages are missing.

Resumption of the investigation in 2019

After Komsomolskaya Pravda had started further unofficial research into this case in the summer of 2018 , the public prosecutor of the Sverdlovsk Ural region announced the resumption of official investigations on February 1, 2019 - the 60th anniversary of the accident. Prosecutor Andrei Kurjakow ruled out most attempts at explanation right from the start and considers a natural disaster to be the most likely cause. Critics therefore do not expect any new knowledge from the new investigation. The procedure was completed in July 2020.

Theories on the cause of the accident

At the beginning of the investigation, the theory emerged that the hiking group had been attacked and murdered by members of the Mansen people . The hikers had pitched their tents just a few meters from a mansian path that led to a Tschum . However, the research showed that the circumstances of death did not fit this theory. Only the footprints of the hikers could be seen. In addition, there was no sign of a fight, and the area in which the bodies were found was not one of the major sacred places of the indigenous people that they might have wanted to defend.

According to another theory, the hikers' tent was buried in an avalanche . The injuries of Dubinina, Solotarew and Tibo-Brinjol can be explained by the pressure of the snow masses. The other, unscathed hikers had cut the tent to free themselves and their injured friends. However, due to inadequate clothing, they eventually froze to death. One of the arguments raised against this theory was that there were no traces of an avalanche.

Another theory is that the ski hikers may have accidentally broken into an unofficial military training site and been the victim of a nuclear test or other training exercise.

The sighted flares, in connection with an enigmatic photo from Krivonishchenko's camera and the rumor that the KGB had forbidden any mention of UFOs , fueled UFO theories.

Some authors suspect a secret service background. In his book, published in 2014 (and translated into German in 2018), an author who wrote under the pseudonym Alexej Rakitin used the following scenario: three of the nine hikers had a connection to the KGB (which the other hikers had no idea about); The aim of the hike was a targeted handover of a sample of strongly radiating, radioactive strontium -90 (applied to sweaters and pants) to western secret agents in order to lay a false track there. After this surrender at Cholat Sjachl had failed and the western spies had been recognized as such, they wanted to kill the group, but without shooting them and laying larger traces. They forcefully forced the members of the group to undress so that they would soon die from cold. However, contrary to expectations, some held out for some time, and so they were brutally killed. The main thing the KGB wanted to know about the case was whether the handover had worked. The files were then closed. Three senior KGB officers were demoted the following year . Perhaps it was those who were responsible for this failed operation.

One of the author's theory on para-scientific topics, Alexander Popoff, states that the tourers were killed by atmospheric electricity ( winter lightning ). Then the cut and torn clothing, the entry and exit wounds, burned flesh, tree branches and clothing, the nature of the blunt injuries and broken bones, the confused behavior, the absence of the tongue and eyes, the temporary bed and the fire under a tree - contrary to any safety instructions - that point to the tent that was left half-naked and without shoes in panic and despite the cold and darkness, and finally to the quick death of the hikers.

American documentary filmmaker Donnie Eichar considered the possibility of panic spreading inside the tent. A possible trigger for him is, in particular, the effect of infrasound as a result of the locally suspected weather events (storm) in connection with the possibility of a Kármán vortex street emerging on the slope .

Reception in literature, media and film

In 1967 the author and journalist Yuri Yarovoi published the novel The Highest Difficulty ( Высшей категории трудности ), which was inspired by the accident. Jarovoi was involved in the search for the group and a photographer in the search campaign and investigation. Since the book was written during the Soviet era, the details of the accident were kept under wraps and Jarovoi avoided publishing anything that was not in accordance with the official position. The book romanticizes the accident and has a far more optimistic ending than the real events - only the group leader is found dead. Jarovoi's colleagues said he wrote two other versions of the novel, both of which were censored. Since Jarovoi's death in 1980, all of his archives, including photos, diaries and manuscripts, have disappeared.

Some details of the tragedy were made public through articles in Sverdlovsk's regional press in 1990. One of the first authors was Anatoly Gushchin. He said the police had given him special permission to study the original files of the investigation and publish the results. However, he noticed that some pages were missing, as well as a mysterious “cover” that was on the material list. At the same time, unofficial photocopies of the files were being circulated among investigators.

Gushchin summarized his studies in the book The Price of State Secret - Nine Lives ( Цена гостайны - девять жизней ). Some researchers criticized the novel for its strong focus on the speculative theory of a "Soviet secret weapon". Nevertheless, the publication aroused great interest. In fact, many who had been silent on this subject for the past thirty years now spoke out. One of them was former militiaman Lev Ivanov, who led the official investigation in 1959. In 1990 he published an article admitting that the investigation team had no rational explanation for the incident. He also received direct orders from high-ranking regional officials to break off the investigation and keep the material secret after the team saw "flying bullets". Ivanov personally believes in a paranormal explanation, especially UFOs.

From 1997 onwards, a regional television station produced several documentaries about the event. With the help of the film crew, Anna Matveyeva published a story under the same title. Much of the book consists of extensive citations from official files, victims' diaries, and interviews with researchers. The book is about a woman who tries to clear up the accident at the Djatlov Pass.

With the support of the State Technical University of the Urals in Yekaterinburg, a Dyatlov Foundation was established. It is managed by Yuri Kunzewitsch, a close friend of Igor Dyatlov and a member of the search team. The foundation is trying to get the Russian authorities to reopen the case. She is also responsible for the maintenance of the Djatlov Museum.

The horror film Devil’s Pass , an American-Russian co-production in found footage style, released in 2013 , is about a group of American students who follow in the footsteps of the Dyatlov expedition 53 years after the accident. The German film premiere took place as part of the Fantasy Film Festival 2013.

In 2014, as part of Animal Planets Monster Week, a documentary was produced in which the American filmmaker Mike Libecki attributed the death of the students to a Yeti who is said to have been startled and angry by fallen rocket fragments . The original title and the German version are "Russian Yeti: The Killer Lives" / "Russian Yeti - Expedition in den Tod".

The computer game Kholat , released in 2015, puts the player in the role of a wanderer who, years after the accident, investigates the incidents there and encounters mysterious phenomena.

literature

- Donnie Eichar: Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident. Chronicle Books, San Francisco 2013, ISBN 978-1-4521-2956-3 .

- Alexander Popoff, Daniela Mattes: The Djatlov Pass Incident: An Investigation That Explains All Confusing Facts. Ancient Mail Verlag, Groß-Gerau 2014, ISBN 978-3-95652-092-1 .

- Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. One of the final secrets of the Cold War. Original title: Pereval Dyatlova (Перевал Дятлова). Translated from the Russian by Kerstin Monschein. btb Verlag, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-641-15405-9 .

Web links

- DyatlovPass.com (information site; English, Russian)

- Claus Jahnel: Extensive documentation and considerations in four parts at Telepolis , 2018:

- Part 1 - The highest level of difficulty. In: Telepolis. 19th August 2018.

- Part 2 - Alien Yetis on Fly Agaric. In: Telepolis. September 9, 2018.

- Part 3 - Two films and two newspapers. In: Telepolis. October 21, 2018.

- Part 4 - "Moderate level of difficulty" ... but yes! In: Telepolis. November 11, 2018.

- Brian Dunning: Mystery at Dyatlov Pass: A look at one of Russia's most bizarre mysteries of mass death. In: Skeptoid.com. (English).

- Alexei Rakitin: Смерть, идущая по следу ... Попытка историко-криминалистической реконструкции обстоятельств гибели группы свердловских туристов на Северном Урале в феврале 1959 г. In: murders.ru. 2011 (Russian, very extensive analysis of the accident).

- Фото 1959. In: infodjatlov.narod.ru. (Russian, 72 pictures).

- Anatoly Gyschtschin: Цена гостайны - девять жизней? Трагедия у Горы Мертвецов: документы и версии. In: Уральская Библиотека / urbibl.ru. 1999 (Russian, "The Price of State Secret - Nine Lives? Tragedy on the Mountain of the Dead: Documents and Versions". Online version of the book).

- The dead from the Djatlov pass

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Svetlana Osadchuk: Mysterious Deaths of 9 Skiers Still Unresolved. In: The St. Petersburg Times . February 19, 2008, accessed August 10, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Анна Матвеева (Anna Matvejewa): Перевал Дятлова (Dyatlov Pass). In: «Урал». 12, 2000, Retrieved October 5, 2009 (Russian).

- ↑ a b c Анатолий Гущин (Anatoly Gushchin): Цена гостайны - девять жизней (The price of the state secret - nine lives) . Уральский рабочий (Ural workers), Sverdlovsk 1990 (Russian).

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 30 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 18.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 30.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 22 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 27 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 28 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 19 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 37.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 159, 884-887.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 886.

- ↑ a b Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlow pass. 2018, p. 78 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 161, 169, 174, 483, 884-887, 899, 909.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 34.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 37 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 42–48.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 51–54, 930 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 86, 95.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 58–62.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 132 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 227, 469.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 248 f.

- ↑ a b Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlow pass. 2018, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 57.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 209–211.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 63.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 84.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 115.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 85–94.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 94–99.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 99-103.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, pp. 104–110.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 142 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 144 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 148 f.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 264 f.

- ↑ a b Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlow pass. 2018, p. 249 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 250.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 256.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 261 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 267 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 271 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 276.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 287.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 207.

- ↑ Quoted from Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 207.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 207 ff.

- ↑ Evgeny Buyanov: Альпинисты Северной Столицы: Разгадка тайны «огненных шаров». In: alpklubspb.ru / Альпинисты Северной Столицы. 2002, Retrieved February 3, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ Claus Jahnel: Part 1 - The highest level of difficulty. In: Telepolis . August 19, 2018, accessed February 3, 2019 .

- ^ Prosecution agencies rule out authorities' involvement in 1959 Dyatlov Pass incident. In: TASS . February 4, 2019, accessed March 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Stefan Scholl: 75 versions of death in the snow - investigation of accidents in the Soviet Union. In: Berliner Zeitung . February 11, 2019, accessed March 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Investigators see avalanche as the cause of the mysterious death of hikers. In: Spiegel.de. July 11, 2020, accessed July 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 202 ff.

- ↑ Alexej Rakitin: The dead from the Djatlov pass. 2018, p. 467 ff.

- ↑ Teodora Hadjiyska: Dyatlov Pass: UFO. In: dyatlovpass.com. Retrieved January 1, 2017 .

- ↑ Jürgen W. Schmidt: The mystery of the death of the Djatlov expedition in 1959 . In: Jürgen W. Schmidt (Ed.): Spies, Fraudsters, Secret Operations. Case studies and documents from 275 years of secret service history . Secret intelligence tape 10 . Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89574-890-5 , pp. 266-289 .

- ↑ Aleksey Rakitin: The dead from the Dyatlov Pass. One of the final secrets of the Cold War . ISBN 978-3-442-71604-3 .

- ↑ Dyatlov Pass Incident. In: Alexander Popoff's website. July 11, 2014, accessed February 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Alexander Popoff: The Dyatlov Pass Incident: An Inquiry That Explains All Confusing Facts , Ancient Mail Verlag, 2014

- ↑ Donnie Eichar: Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident.

- ↑ Юрий Яровой (Juri Jarowoi): Высшей категории трудности (The highest level of difficulty) . Средне-Уральское Кн.Изд-во (Mittel-Ural-Buchverlag), Sverdlovsk 1967 (Russian).

- ↑ Лев Иванов (Lev Ivanov): Тайна огненных шаров (The Secret of Fireballs) . Ленинский путь (Lenin Way), Qostanai November 22, 1990 (Russian).

- ↑ История ТАУ. In: ТАУ - Телевизионное Агентство Урала (Ural Television Agency). Retrieved April 24, 2017 (Russian).

- ^ Devil's Pass (2013). In: IMDb . Retrieved June 12, 2015 .

- ↑ Verena M. Dittrich: The deadly secret of the Djatlow group. In: Welt Online . May 30, 2014, accessed February 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Kholat. In: IMGN.PRO. Retrieved June 12, 2015 .