Union pour la democratie française

The Union pour la Démocratie Française ( UDF , German Union for French Democracy ) was a party alliance from 1978 to 1998 , then a political party in France until 2007 . It united Christian-democratic , liberal and centrist roots and occupied the center or the right center of the French party landscape. In addition, she represented very pro-European positions.

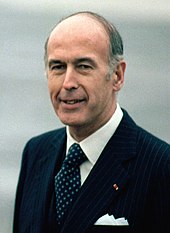

The UDF was founded in 1978 by the then liberal President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing . Despite initially great electoral successes - 23.9 percent in the parliamentary elections in 1978 - he did not succeed in permanently establishing a force of the center on which the power of a state president could have been based. Giscard therefore also worked with the conservative Gaullists of the RPR , with whom the UDF often made electoral agreements and repeatedly formed government coalitions. The member parties continued to exist, but it was also possible to become a direct member of the UDF.

In 1998 the party was renewed under the name Nouvelle UDF after the Liberal Conservatives left it. In 2002 the UDF lost some of its members to Jacques Chirac's center-right rallying party UMP . The last chairman of the UDF, François Bayrou , founded a new party in May 2007, the Mouvement démocrate (MoDem). Some right-wing party representatives who support the presidency of Conservative Nicolas Sarkozy then formed the Nouveau Center party . Other parliamentarians, especially senators, remained independent.

In the European Parliament , the UDF was a member of the European People's Party (EPP) from 1991 to 2004 . Then the UDF co-founded the European Democratic Party (EDP) or the Group Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE).

Established in 1978

In the Fifth French Republic (since 1958 until today) Gaullism was the decisive political force, the right-wing, national-conservative collective movement of Charles de Gaulle . After de Gaulle, his prime minister, Georges Pompidou, became the new president. He died in office in 1974. His successor was the Liberal Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who was more successful than the Gaullist candidate in the first ballot.

Between the Gaullists on the one hand and the Socialists on the other, there were a large number of parties at the center of the party spectrum. In the broadest sense they belonged to liberalism or a Christian-democratic current. The parties of the center could in fact only support a left or a right presidential candidate, and in the parliamentary elections, too, because of the majority voting system, one's own electoral success depended on cooperation with the left or right.

The Christian Democrats united in the Center des démocrates sociaux in 1976, the right-wing liberals in the Parti républicain 1977. However, both formations were not as strong as the initiators had hoped. Before the 1978 general election, no non-Gaulle group could take on the Gaullists. A new alliance was founded on February 1, 1978, including the left-liberal Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste : the Union pour la Démocratie Française . The name refers to one of Giscard's books, entitled Démocratie Française .

The clubs perspectives et réalités and the Mouvement démocrate socialiste de France soon followed . In addition, other people joined it as members without having previously belonged to one of the parties mentioned ( Adhérents directs de l'UDF , UDF-AD).

| Political party | History and direction | later way | Famous pepole |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parti républicain (PR) | Liberal-conservative, emerged from the Center national des indépendants et paysans (1949/1951), later the Fédération nationale des républicains et indépendants (1966) | Démocratie libérale since 1997 , with the UMP since 2002 | Giscard d'Estaing, Michel Poniatowski , Jean-Claude Gaudin , François Léotard |

| Center des democrates sociaux (CDS) | Christian-democratic-centrist, from the tradition of the “People's Republicans” of the Mouvement républicain populaire , who were powerful after the end of the war ; 1967 Fraction Community Progrès et démocratie moderne (PDM); In 1969, one third of the MPs supported the Gaullist government and founded the Center Démocratie et Progrès (CDP); 1976 CDS as a merger of PDM and CDP | from 1995 Force démocrate , incorporated in Nouvelle UDF in 1998 , since 2007 MoDem or NC | Jean Lecanuet , Pierre Pflimlin , Nicole Fontaine , François Bayrou |

| Parti radical (wheel) | Bourgeois, left-wing liberal, one of the most important parties before 1958, since then a small party. 1972 Split of the left-liberal Parti radical de gauche , since then often called Parti radical valoisien ; since then more in the right center | from 2002 to 2011 part of the UMP , then the UDI | Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber , Françoise Giroud , Jean-Louis Borloo |

| Mouvement démocrate socialiste de France (MDSF) | Social-democratic, founded in 1973 as an anti-communist split from the socialists , renamed Parti Social-Démocrate (PSD) in 1982 | from 1995 Force démocrate , incorporated into Nouvelle UDF in 1998 , since 2007 mainly NC or UDI | Max Lejeune , André Santini , Émile Muller |

| Fédération Nationale des Club Perspectives et Réalités | First in Paris in 1965, then on a tour of France Giscard founded in 1966 clubs of entrepreneurs and freelancers, closely associated with the liberal conservatives | from 1995 Parti populaire pour la démocratie française ; from 2002 to 2010 as a Convention démocrate part of the UMP, from 2012 in the UDI | Jean-Pierre Fourcade , Alain Lamassoure , Hervé de Charette |

Development until 1995

In the elections in March 1978, shortly after it was founded, the party alliance cut an exceptionally good figure: With 21.45 percent in the first ballot, it was only just behind the Gaullists with 22.62 percent. Even in later elections, the centrists were usually only a little behind the Gaullists. Yet the Gaullists continued to be the dominant force on the right and in France in general, while the centrists could only hold their own in parliamentary elections in cooperation with them. In the government too, both groups mostly worked together. In this respect, the founding of the UDF changed little.

The Christian Democratic, “republican” (ie conservative-liberal) and “radical” (ie social-liberal) currents remained within the UDF. Preserving the old structures helped to retain local voters. According to political scientist Alexis Massart, it was never a priority for the UDF to create a unified party program; but standing together in elections ensured that the ideological similarities were emphasized. Republicans and Christian Democrats converged on the basis of a kind of socially influenced liberalism, combined with great European friendliness.

In 1981 Giscard was not re-elected, also because the Gaullists had only half-heartedly supported him. The new president, the socialist François Mitterrand , initially worked with the communists, but when he was re-elected in 1988 at the latest, he tried to appeal to a broader potential of voters. The UDF candidate in this election was Raymond Barre , who failed with 16.5% in the first ballot. While the CDS campaigned resolutely for its own candidate, the Parti républicain only supported him half-heartedly and made it clear that they saw Jacques Chirac from the RPR as equally eligible.

Since the left had only a narrow majority after the subsequent parliamentary elections in 1988 , Mitterrand's moderate-socialist Prime Minister Michel Rocard tried to get an overture , ie an opening for bourgeois forces, and accepted members of the UDF into his government . These included Michel Durafour (Rad) as Minister of State for Administrative Reform and Jean-Pierre Soisson (PR) as Minister of Labor. However, the leadership of the UDF rejected the overture and threatened to be expelled from the party. Ministers Soisson and Durafour then left the UDF and founded the Mouvement des réformateurs , which, however, remained meaningless in elections. The Christian Democrats of the CDS saw an opportunity to position themselves more independently and not participate in the right-wing opposition. They remained in the UDF, but formed their own parliamentary group as the Union de Center (until 1993) and worked with the Rocard government. Because of the permanent connection with the UDF, which entered into electoral alliances with the Gaullists, it was not possible to consolidate the image of an independent Christian democracy. This became all the more difficult because of the growing number of elections, as France was given more administrative levels through decentralization. For the elected officials who were dependent on the right-wing electoral alliance, taking an independent course was dangerous.

There were also differences in the European elections in 1989 : Officially, the UDF ran with a joint list with the RPR under the leadership of Giscard d'Estaing. However, since the RPR took a rather slower position with regard to European integration, the European-federalist Christian Democrats, together with the former President of the European Parliament Simone Veil (a non-party liberal), put together their own list called Le Center pour l'Europe . This came to 8.4% of the vote, while the joint UDF-RPR list fell to 28.9%. Most of the “official” UDF MEPs and Simone Veil then sat in the liberal parliamentary group, while the MEPs from the CDS were in the Christian Democratic EPP parliamentary group . Giscard d'Estaing tried to persuade these two factions to merge. When this failed, he switched to the EPP group with the other liberal UDF delegates (except for Veil) at the end of 1991. This was clearly strengthened and developed from a purely Christian Democratic to a liberal-conservative group, while the European liberals consequently no longer had a member party from France.

After the landslide victory of the center-right camp in the parliamentary elections in 1993 , the UDF was reunited and represented by numerous ministers in the Balladur cohabitation cabinet (including Simone Veil for social affairs, Pierre Méhaignerie (CDS) for justice, François Léotard (PR) for defense) , François Bayrou (CDS) for Education). With 207 of the 577 seats in the National Assembly, the UDF was at the height of its strength. For the European elections in 1994 , the - reunited - UDF ran again together with the RPR. Nevertheless, these combined only came to 25.6%. This was due to the appearance of the nationally conservative, EU-skeptical Majorité pour l'Autre Europe list under the leadership of former UDF member Philippe de Villiers . This came to 12.3% and later became the Mouvement pour la France (MPF).

In 1995 the electoral alliance of RPR and UDF was burdened by the candidacy of Édouard Balladur . This Gaullist prime minister ran for the presidential candidates with the help of the UDF, while the Gaullists competed with Jacques Chirac . Above all, the renunciation of a candidate from the UDF itself meant a failure to position oneself in a presidential election, which, because of the great importance of presidential elections, meant presenting oneself as a subordinate force. In addition, individual UDF politicians, including chairman Giscard d'Estaing, refused to support Balladur and instead spoke out in favor of Chirac.

Transition to the new UDF 1995–1998

The years 1995 to 1998 brought a considerable change in the composition and structure of the UDF. The re-election of François Léotard as chairman of the Parti républicain meant a shift to the right of the liberal-conservative component and a defeat of the “Giscard-loyalists” (giscardiens) . These then left the PR. The “Giscardist” clubs Perspectives et Réalités changed in July 1995 into a separate party within the UDF: the Parti populaire pour la démocratie française (PPDF), the z. B. Hervé de Charette and Jean-Pierre Raffarin joined. Other giscardiens (e.g. Charles Millon ) and Giscard d'Estaing himself also left the PR, but became adhérents directs (direct members) of the UDF. In November 1995, the Christian Democratic CDS merged with the small social democratic PSD. The result was called Force démocrate and was led by François Bayrou, whose goal was to transform the UDF from a loose party alliance into a unified party. However, the Republican and Radical Parties refused.

In June 1997, the Parti républicain, led by Alain Madelin, was renamed Démocratie Libérale (DL) and turned back to traditional, right-wing liberalism. The regional elections in March 1998 became a point of contention between the DL and the centrist components. In regions where the bourgeois parties did not have a majority, some UDF candidates could also be elected regional presidents with the votes of the right-wing extremist Front National (including Charles Millon in Rhône-Alpes and Jean-Pierre Soisson in Burgundy ). The DL accepted this, while the Force démocrate under Bayrou categorically rejected any collaboration with the Front National and pushed for the relevant regional presidents to be excluded from the UDF. Because of these tensions, the DL left the party alliance in May 1998. A minority of the members of the DL who wanted to remain in the UDF (e.g. François Léotard, Gérard Longuet ) then founded the Pôle républicain indépendant et libéral (PRIL), which became the fourth component of the UDF. Soon afterwards, the DL sank into political insignificance.

After the departure of the DL, the centrist Force démocrate was the largest part of the UDF and Bayrou was elected as the new chairman of the Union in September 1998. He took the opportunity and at the party congress in November of the same year decided to convert the UDF from an alliance to a unified party. In this Nouvelle UDF the Christian Democrat dominated Force démocrate, the PRIL, the PPDF and the UDF- adhérents directs were absorbed . Only the traditional Parti radical retained its independence and remained an associated party of the UDF. The old UDF alliance of liberals and Christian Democrats was strong enough to balance Gaullism in the right-wing subsystem, while the new UDF, as a second-rate formation, was far more vulnerable to the RPR's claim to leadership.

Reshaping the center right and the UMP 2002

Soon François Bayrou expressed his intention to distance himself politically from the RPR and put up a separate list of the UDF for the European elections in 1999 , in competition with that of RPR-DL. However, this strategy fueled resistance within its own party and not a few members of the UDF decided to support Jacques Chirac's candidacy in the 2002 presidential elections rather than that of François Bayrou. Despite a relative success with the fourth best result and 7% of the vote, François Bayrou was no longer able to oppose the creation of the UMP on the initiative of Jacques Chirac and Alain Juppé . In the UMP (then Union pour la majorité présidentielle / “Union for a majority of the president”), which was founded on the day after the first ballot on April 21, 2002 , which aimed to unite all center-right parties. The Parti radical valoisien then switched from the UDF to the associated party of the UMP.

A significant part of the UDF MPs left the party to join the UMP. The founder of the UDF, Giscard d'Estaing, also went this way; also z. E.g. the EU Parliament President Nicole Fontaine , the mayors of Strasbourg and Toulouse, Fabienne Keller and Philippe Douste-Blazy , and the future EU Commissioner Jacques Barrot . Nevertheless, in the elections to the National Assembly in the same year, the UDF managed to maintain its parliamentary group status with 29 members. This forum enabled the movement to express diverse views and to oppose the government of Jean-Pierre Raffarin on several occasions .

In this way, when some foresaw its dissolution, the party was able to regain a certain degree of influence and weight in the elections, such as the first round of the regional elections in 2004 and the European elections in 2004 (12%) in June of the same year should confirm. According to general opinion, this success was based on alternatives that the party offered bourgeois-conservative voters who were not satisfied with the government's policies, especially on social issues, but also on their involvement in European politics , with which they also voted for voters outside of it traditional sphere of influence.

On the occasion of the 2004 European elections , the UDF left the Christian Democratic party alliance European People's Party , which it accused of being too skeptical about key European issues, in order to found a new, more centrally-oriented and decidedly pro-European alliance - the European Democratic Party . This formed an alliance of liberals and democrats for Europe with the liberals in the European Parliament .

On June 8, 2005, after Dominique de Villepin's speech to the National Assembly about the plans for the general direction of his government's policy, the UDF parliamentary group refused to vote in the vote of confidence for the new government for the first time since 2002 . In order to also symbolically express its repositioning as an independent force of the center, the party changed its logo and its party color in 2005: If it had previously identified itself as a representative of the center-right camp with shades of blue, the public appearance was from now on dominated by the color orange .

Dissolution of the party

In the presidential election in April 2007 Bayrou came in third place with 18.6% of the vote - the best result for a UDF candidate since the era of Giscard d'Estaing, especially with young voters, he did well. While the UDF had always made a recommendation for the remaining candidate in the center-right camp in the second ballot, Bayrou now refused to do so. He even stated explicitly that he himself would not vote for Nicolas Sarkozy of the conservative UMP. Several UDF MPs, including board members André Santini , Hervé Morin and Franoçis Sauvadet , nevertheless called for support for Sarkozy, who also won the election.

In the run-up to the parliamentary elections in June 2007 , the UDF split. Bayrou wanted to contest the election under the new name Mouvement démocrate (MoDem; "Democratic Movement") and without any agreements with the left or right camp. The majority of party members followed this centrist line. The majority of MPs (18 out of 29), who usually owed their parliamentary seats to agreements with the Conservatives, found this strategy too risky. They founded the Nouveau Center ("New Center"; initially also called Parti Social Libéral Européen ) under the leadership of Hervé Morin, who contested the election as part of the Majorité Presidentielle (presidential majority ) in alliance with Sarkozy's UMP. This strategy proved to be far more successful: The Nouveau Center won 22 seats - enough for a parliamentary group of its own - and was then represented in the government by several ministers. The MoDem, which ran independently, received 7.6 percent of the vote, but this was only reflected in three seats due to the majority vote.

Some senators, around Jean Arthuis , did not join the Mouvement démocrate or the Nouveau Center after the split. They remained independent and continued to appeal to the UDF. The joint parliamentary group in the Senate was retained, and Arthuis tried (unsuccessfully) to unite both parties in a revived UDF with his alliance Rassembler les Centristes - Alliance Centriste .

In autumn 2009, the Nouveau Center added L'UDF d'aujourd'hui (“Today's UDF”) to its name . At the same time, the Alliance Centriste chose the slogan L'UDF de demain ( The UDF of tomorrow ) as its motto. At the end of 2009, the co-founder of the UDF and former Foreign Minister Hervé de Charette , who switched to the UMP with his liberal-conservative group Convention démocrate in 2002 , announced that after the UMP “ shifted to the right” he would leave this party and move to the Nouveau Center . Since he had personally patented the name Union pour la Démocratie Française several years ago, and since these patents had never been contested by MoDem, he now affirmed that he owned this name and allowed the Nouveau Center to use the abbreviation UDF for itself claim. The committee of the Association UDF (UDF-Verein), which consists of members of the UDF party executive on the day of its dissolution and which is provisionally responsible for the party's legacy, only includes MoDem, Alliance Centriste and non-party mandataries. This committee vehemently criticized the NC's plan and threatened to challenge any attempt to use the acronym UDF. In contrast, the founder of the UDF, former President Giscard d'Estaing, agreed to the use of "UDF" by the Nouveau Center.

Finally, the Nouveau Center , Alliance Centriste , Parti Radical and Convention démocrate merged in autumn 2012 to form the Union des démocrates et indépendants (UDI). This was described by journalists as a reincarnation of the UDF because it unites similar political currents and occupies a comparable position in the political spectrum. The Mouvement démocrate did not join the UDI, but entered an electoral alliance with it for the 2014 European elections and subsequent elections, which seems to have ended the disputes over the UDF's “legacy”.

Internal party structure (as of 2007, before the party was dissolved)

Chairman:

- François Bayrou - MP and member of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques Council

Deputy authorized representative:

- Hervé Morin - Chairman of the UDF parliamentary group in the National Assembly.

- Michel Mercier - Chairman of the UDF party grouping in the Senate

- Marielle de Sarnez - Chair of the UDF Group in the European Parliament

- Jacqueline Gourault - Chair of the electoral group of the UDF

Vice-chairman:

- Pierre Albertini - Deputy Mayor of Rouen

- Jean Arthuis - Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Chairman of the Mayenne Department Council

- Bernard Bosson - Deputy Mayor of Annecy

- Jean-Louis Bourlanges - MEP

- Anne-Marie Comparini - MP for the Rhône department

- Gilles de Robien - Minister of Education

- André Santini - Mayor of Issy-les-Moulineaux

Press officer : François Sauvadet - Member of the Côte-d'Or department

List of party conventions

- February 1979: 1st Paris Congress

- November 1982: Pontoise Congress

- November 1998: Lille Congress

- December 2000: Angers Congress

- December 2001: Amiens Congress

- January 2003: 2nd Paris Congress

- January 21-23, 2005: 3rd Party Congress in Paris

- 28th and 29th January 2006: Extraordinary Congress in Lyon

- November 30, 2007: Extraordinary Congress of Villepinte , confirmed the transition to the Mouvement démocrate

Party leader

- 1978-1988: Jean Lecanuet

- 1988-1996: Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

- 1996-1998: François Léotard

- 1998-2007: François Bayrou

Election results in parliamentary elections

- Elections to the National Assembly 1978 : 23.9% - 112 seats

- Elections to the National Assembly 1981 : 21.7% - 53 seats

- 1986 National Assembly elections : 15.5% - 127 seats

- Elections to the National Assembly in 1988 : 18.5% - 129 seats

- National Assembly elections 1993 : 19.1% - 213 seats

- Elections to the National Assembly 1997 : 14.2% - 108 seats

- European elections 1999 : 9.3% - 9 seats

- Elections to the National Assembly 2002 : 4.8% - 29 seats

- 2004 European elections : 12.0% - 11 seats

Party youth

→ Main article: Jeunes UDF

The Jeunes UDF was founded in 1998 on the occasion of the unification of the UDF, in which the members between the ages of 16 and 35 came together. Represented in all organs of the party, they are actively involved by expressing their opinions in internal party debates and putting them up for discussion. In contrast to numerous other political youth movements, the organization knows its own structures and chooses its representatives and leaders independently:

- a national chairman - elected by all members for two years, since September 2004 Arnaud de Belenet;

- a Politburo at the national level - to be elected at the same time as the President and charged with enlivening the daily work of the movement;

- a national council - made up of members selected by the regional groupings who meet regularly for thematic meetings.

With similar organizational structures, there are independent groups of party youth at the level of the départements:

- the regional chairman - elected for two years by all the members of the regional grouping;

- the regional Politburo - to be elected at the same time as the chairman and charged with stimulating the work of the regional grouping.

Web links

This article is based on a translation of the French Wikipedia article .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197–215, here p. 201.

- ^ Udo Kempf: The bourgeois parties of France: The Rassemblemt Pour La République (RPR), the Parti Républicain (PR) and the Center des Démocrates Sociaux (CDS). In: Hans-Joachim Veen (Ed.): Christian-Democratic and Conservative Parties in Western Europe 2, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 1983, pp. 125-314, here p. 154.

- ^ Udo Kempf: The bourgeois parties of France: The Rassemblemt Pour La République (RPR), the Parti Républicain (PR) and the Center des Démocrates Sociaux (CDS). In: Hans-Joachim Veen (Ed.): Christian-Democratic and Conservative Parties in Western Europe 2, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 1983, pp. 125-314, here p. 146.

- ^ Udo Kempf: The bourgeois parties of France: The Rassemblemt Pour La République (RPR), the Parti Républicain (PR) and the Center des Démocrates Sociaux (CDS). In: Hans-Joachim Veen (Ed.): Christian-Democratic and Conservative Parties in Western Europe 2, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 1983, pp. 125-314, here p. 159.

- ^ Udo Kempf: The bourgeois parties of France: The Rassemblemt Pour La République (RPR), the Parti Républicain (PR) and the Center des Démocrates Sociaux (CDS). In: Hans-Joachim Veen (Ed.): Christian-Democratic and Conservative Parties in Western Europe 2, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 1983, pp. 125-314, here pp. 145/146.

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197–215, here pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Joachim Schild: Politics. In: Joachim Schild, Henrik Uterwedde: France. Politics, economy, society. 2nd edition, VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, p. 62.

- ↑ Udo Kempf: The parties of the right between unity and dissolution. In: Frankreich-Jahrbuch 1988. pp. 87–114, on p. 87.

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197-215, here pp. 204/205.

- ^ Paul Hainsworth: France. In: Juliet Lodge: The 1989 Election of the European Parliament. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 1990, pp. 126-144, at pp. 130-132, 141.

- ^ David Hanley: Beyond the Nation State. Parties in the Era of Integration. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, pp. 125-127.

- ^ Thomas Jansen, Steven Van Hecke: At Europe's Service. The Origins and Evolution of the European People's Party. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2011, p. 225.

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197–215, here p. 208.

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197–215, here p. 208.

- ↑ Alexis Massart: The Impossible Resurrection. Christian Democracy in France. In: Steven Van Hecke, Emmanuel Gerard (Eds.): Christian Democratic Parties in Europe since the End of the Cold War . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2004, pp. 197–215, here p. 209.

- ^ Franck Dedieu: L'orange, la couleur challenger. In: L'Express , November 1, 2005.

- ^ Daniela Kallinich: The Mouvement Démocrate. A party at the center of French politics. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2019, p. 482.

- ↑ Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Richard Nadeau, Éric Bélanger: French Presidential Elections. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke (Hampshire) / New York, p. 18.

- ↑ L'ancien ministre Hervé de Charette quitte l'UMP

- ↑ http://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2009/12/08/herve-de-charette-transfuge-de-l-ump-attendu-au-nouveau-centre_1277484_823448.html

- ↑ Guerre de clochers et mise en demeure autour du sigle UDF

- ↑ Giscard aprrouve le projet de Morin de l'UDF relancer

- ↑ Alba Ventura: "Les Carnets d'Alba": l'UDF n'est plus, vive l'UDI! RTL, September 19, 2012.

- ↑ Christophe Forcari: Pour lancer l'UDI, Borloo déterre l'UDF. In: La Liberation , October 21, 2012.

- ↑ UDF, MoDem, UDI ... L'interminable recomposition du center. In: C Politique on France 5 , December 9, 2012.