Weizsacker

Weizsäcker and Weitzsäcker is the name of Palatine - Württemberg sex from the original millers that in - line in the 19th century into the - the Öhringer educated middle class rise. The Tübingen theologian and university chancellor Karl Heinrich Weizsäcker was given the personal nobility in 1861 . His son Karl Hugo was given the personal nobility in 1897 and in 1916 he was raised to the status of hereditary baron as Prime Minister of Württemberg . Family members also held prominent positions in the Weimar Republic , in the Nazi state and in the Federal Republic of Germany.

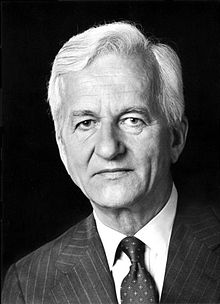

The best-known representative of the family is the Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker, who died in 2015 .

history

Origin of gender

The Weizsäcker can be traced back to relatives of the 1294 knight Peter Wazach (Wadtsacher), who was a vassal of Count Walram I of Zweibrücken . The even childless Peter Wazach was apparently a member of the Watsacher family from Weilheim in Upper Bavaria , where they owned the Waitzacker estate, which still exists today.

The documented lineage of the family, which probably comes from the Waadsacker Mühle (also Woodsacker Mühle, today Woogsacker Mühle), a former property of Peter Wazach near Niederbexbach , begins with Friedrich Weidsecker, who was born around 1535 and was a miller at Kleeburg in Lower Alsace .

Friedrich Weidsecker's son Friedrich Wadsacker migrated to Waldmohr not far from Niederbexbach before 1610 and took over the Waldmohrer Mühle. His son Nicolaus Weizsäcker (also Waadsecher, Wadsacker, Waidsacher, Waidsecker and Weidtseckher) (1612–1673) acquired his father-in-law's mill, the Bernhardsmühle near Neuenstein , in 1650 , where he became the progenitor of the twelve lines of the family that are flourishing today, most of them a branch of the Öhringer line achieved a remarkable social rise.

The miller's trade , which has been practiced for many generations , dates back to the Middle Ages and was considered disreputable for various reasons. In many places the profession of miller was one of the "dishonest" professions until well into the 19th century . The millers therefore counted among the lower classes and stood on the edge of the class. In some cases, family members pursued this acquisition, which is now an honorable trade, in their ancestral home until recently (as of 1987).

Öhringer line

The Öhringer line, one of twelve lines of the family that is flourishing today, goes back to Gottlieb Jacob Weizsäcker (1736–1798). He first learned the miller's trade in what is now Eckartsweiler , a suburb of Öhringen , but then switched to the service of the Counts of Hohenlohe-Öhringen and in 1768 became court cook of the employer who had meanwhile been raised to prince in the Öhringen residence, which has around 3,000 residents . The older son Carl Friedrich Gottlob Weizsäcker (1774-1835) was the city mayor of Öhringen. His descendants remained true to their craft roots and became primarily opticians for generations .

The training of the talented younger son Christian Ludwig Friedrich Weizsäcker (1785–1831) was promoted by the employer, as was not unusual at that time. Although the family fell into poverty after Gottlieb Jacob Weizsäcker's death, the further promotion of the son ensured social advancement. In 1806 the principality was mediatized , and Öhringen was now an upper administrative city belonging to the Kingdom of Württemberg . Christian Ludwig Friedrich Weizsäcker made it to the canon preacher in Öhringen in 1829 after the city pastor had given up the less paid position. Although the preacher was the prince's spiritual advisor, he was only formally prince since 1806, but in reality he was meaningless. Christian Weizsäcker, of poor health, barely exercised his office from the start and died two years later, leaving his 34-year-old widow unsupervised.

Christian Ludwig Friedrich Weizsäcker's successful connection to the educated bourgeoisie , however, seems to have laid the groundwork for further advancement - his wife, as a “distressed widow”, succeeded in admitting his son Carl Heinrich Weizsäcker to the Schöntal seminar in 1839 . In 1859 he became senior consistorial advisor - “the poor boy from Öhringen now had rank and name.” He later became professor of theology and in 1861 he was finally raised to the rank of personal nobility. A younger brother was the later historian Julius Weizsäcker .

From the middle of the 19th century, this branch of the family was firmly rooted in the educated bourgeoisie and has since produced well-known members who shape the image of the widely ramified family in public. Shortly before the end of the German Empire , a member of the Öhringen line succeeded in advancing into the hereditary nobility : Karl Hugo Weizsäcker , Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Württemberg , was only raised to the personal nobility status in 1897 and hereditary baron in 1916 .

High offices in four different systems of government

The fact that the Weizsäcker family produced civil servants and politicians (Prime Minister, State Secretary, Federal President, Member of Parliament) in four different systems of government ( Imperial Era , Weimar Republic, Nazi dictatorship, Federal Republic) makes them one of the few "political families" in Germany while in in other countries with greater historical continuity (e.g. USA, Great Britain), political families are much more common. Against the background of the very changeable German history, the political philosopher Gerard Radnitzky questions critically and ironically whether the Weizsäcker could possibly speak of an “innate political correctness ”.

The Weizsäcker in the Weimar Republic

The publicist Ralph Giordano attested that the family had an attitude at the time that was not atypical for parts of the nobility and the educated bourgeoisie and that contributed to the failure of the Weimar Republic:

"When Karl Hugo von Weizsäcker , honored, died in February 1926, the political family terrain was marked: alienation from democracy, yes-hostility, bias in the authoritarian state thinking of monarchical stamping."

The Weizsäcker in the Nazi dictatorship

Despite an inner distance from National Socialism in terms of educated citizens, a number of well-known members of the family also made careers in the Third Reich . In this context, the following family members of the Öhringer branch should be emphasized:

The diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker was State Secretary in the Foreign Office under Ribbentrop from 1938 to 1943 , joined the NSDAP when he took office (membership number 4 814 617) and was sentenced to five years imprisonment in the Wilhelmstrasse Trial of Nuremberg against senior officials of the NS state, under partly because of complicity in the deportation of French Jews. His role is controversially discussed by historians, as he tried in vain obstruction to prevent the outbreak of war in the first phase of his term of office, and later had various contacts with the resistance against Hitler, which he did not join.

The physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker was not a member of the NSDAP, but during the Nazi era he worked on the development of nuclear weapons at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in a group that also included Werner Heisenberg and Otto Hahn . At the beginning of the war, Weizsäcker hoped that the uranium project would give him political influence . He developed the theory of the nuclear weapon with plutonium and was one of the main authors of the patent application for a nuclear weapon in 1941. Independent historians conclude that, in comparison to other participants in German nuclear weapons research ( Kurt Diebner , Walther Gerlach ) , Weizsäcker and Heisenberg obviously did not use all the means at their disposal to supply the Nazis with nuclear weapons. On the other hand, the circumstances would not have caused them to interrupt or delay their work, let alone to offer resistance against National Socialism.

Viktor von Weizsäcker , a physician, existential-anthropological theorist of psychotherapy and co-founder of psychosomatic medicine, was not a member of the NSDAP, but he hoped that the Nazi revolution would overcome the societal and social crisis that he felt strongly and believed in his medical ideas could make a contribution to this. In his lectures, among other things, he dealt with the term “doctrine of extermination” and welcomed the law on the prevention of genetically ill offspring . From 1942 to 1944 , Hans Joachim Scherer conducted research at Weizsäcker's institute in Breslau on brains that came from killed mentally handicapped children. According to medical historian Udo Benzenhöfer, it is impossible that Weizsäcker initiated this research and there is no evidence that he knew about the origin of the preparations. The question arises, however, as to whether Weizsäcker "as director of the institute should not have asked how Scherer came up with the large number of preparations."

The Weizsäcker in the Federal Republic

In the post-war period, the confrontation with the Nazi era played a major role for the family . Outwardly, the justification of one's own actions was initially in the foreground. This is particularly evident for Ernst von Weizsäcker in the Wilhelmstrasse trial, in which Richard von Weizsäcker worked for his father as an auxiliary defender. But Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker also developed a strategy of justification, as can be seen in the minutes of the meetings of the physicists interned in Operation Epsilon from Farm Hall . At the same time, the preoccupation with one's own errors and guilt sets in. This is likely to have contributed to the decisive role played by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker in the Göttingen Declaration against the nuclear armament of the Bundeswehr.

For the later Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker , the public and private confrontation with the era of National Socialism by his father, his eldest brother and his uncle, in addition to his own almost six years of participation in the war as a soldier, was certainly formative. It can be assumed that this family history also had a decisive influence on his most famous speech as Federal President on May 8, 1985 on the 40th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe and the Nazi tyranny .

coat of arms

The baronial coat of arms after the diploma of 1916 shows three golden ears of wheat in blue on a green ground (corresponding to the family coat of arms of the sex, after family seals since the 18th century, alluding to the family name and the miller profession of the ancestors). A natural birch tree or maypole (this crest ornament because of the wife of the ennobled, a born from Meibom ), grows out of a sloping trunk on the helmet with blue-gold covers .

Well-known namesake

Master list of the Öhringer line

-

Gottlieb Jacob Weizsäcker (1736–1798), court cook of the princes of Hohenlohe-Öhringen in Öhringen; ⚭ I Elisabeth Margaretha Scheuermann (1739–1779); ⚭ II Dorothea Carolina Greiß (1758 - after 1816)

- (I) Carl Friedrich Gottlob Weizsäcker (1774–1835), City School of Öhringen; ⚭ Johanna Rosalie Friederike Bratz (1789–1860)

- Julius August Franz Weizsäcker (1817–1860), pharmacist; married twice and had six children

- (II) Christian Ludwig Friedrich Weizsäcker (1785–1831), preacher from Öhringen ; ⚭ Sophie Rößle (1796–1864)

- Hugo Weizsäcker (1820–1834)

-

Karl Heinrich von Weizsäcker (1822–1899), Protestant theologian, Chancellor of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen; ⚭ Auguste Sophie Dahm (1824–1884)

- Sophie Auguste Weizsäcker (1850–1915), ⚭ Adolf von Bilfinger (1846–1902), theologian

-

Karl Hugo Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1853–1926), Minister-President of Württemberg from 1906 to 1918; ⚭ Paula von Meibom (1857–1947)

- Carl Victor Weizsäcker (1880–1914), Legation Councilor , fallen

-

Ernst Heinrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), diplomat and State Secretary in the Foreign Office 1938–1943; ⚭ Marianne von Graevenitz (1889–1983)

-

Carl Friedrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1912–2007), physicist and philosopher; ⚭ Gundalena Wille (1908–2000), Swiss historian

The physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker , 1982

The physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker , 1982-

Carl Christian Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1938), professor of economics; ⚭ Elisabeth von Korff (* 1938)

- Elisabeth Freiin von Weizsäcker (* 1964), ⚭ Alexander Freiherr von Bethmann (* 1970)

- Johannes Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1973), musician

-

Ernst Ulrich Michael Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1939), natural scientist and politician; ⚭ Christine Radtke (* 1944), biologist

- Jakob Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1970), economist ⚭ Eva Corino (* 1972), journalist and writer

- Paula Bleckmann b. Freiin von Weizsäcker (* 1972), media educator, ⚭ Frank Bleckmann (* 1970), judge

- Elisabeth Raiser b. Freiin von Weizsäcker (* 1940), historian; ⚭ Konrad Raiser (* 1938), theologian

-

Heinrich Wolfgang Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1947), professor of mathematics; ⚭ Dorothea Grassmann (* 1944), doctor

- Georg Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1973), professor of economics, ⚭ Dorothea Kübler (* 1966), professor of economics

-

Carl Christian Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1938), professor of economics; ⚭ Elisabeth von Korff (* 1938)

- Ernst Viktor Weizsäcker (* / † 1915)

- Adelheid Marianne Viktoria Freiin von Weizsäcker (1916–2004), ⚭ Botho-Ernst Graf zu Eulenburg-Wicken (1903–1944)

- Heinrich Viktor Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1917–1939), fallen

-

Richard Karl Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1920–2015), Federal President 1984–1994; ⚭ Marianne von Kretschmann (* 1932), patron of various foundations

- Robert Klaus Freiherr von Weizsäcker (* 1954), Professor of Economics

- Andreas Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1956–2008), artist and professor of art

- Marianne Beatrice Freiin von Weizsäcker (* 1958), lawyer and freelance journalist

- Fritz Eckhart Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1960–2019), doctor and professor of medicine

-

-

Viktor Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1886–1957), neurologist; ⚭ Olympia Curtius (1887–1979)

- Robert Karl Ernst Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1921–1942), missing

- Ulrike Gerda Freiin von Weizsäcker (1923–1948)

- Eckhardt Freiherr von Weizsäcker (1925–1945), fallen

- Cora Freiin von Weizsäcker (1929–2009), ⚭ Siegfried Penselin (1927–2014), professor of physics

- Paula Freiin von Weizsäcker (1893–1933), farmer

- Marie Auguste Weizsäcker (1857–1939), ⚭ Paul von Bruns (1846–1916), surgeon

- Julie Weizsäcker (* / † 1861)

-

Julius Ludwig Friedrich Weizsäcker (1828–1889), historian; ⚭ Agnes beef (1835–1865)

- Julius Hugo Wilhelm Weizsäcker (1861–1939), lawyer; ⚭ Julie Stölzel (1861–1944)

- Adolf Weizsäcker (1896–1978), psychologist and educator; ⚭ I Lucy Bierich (1892–1963); ⚭ II Käthe Hoss (1903–1997), doctor; the second marriage resulted in two daughters

- Luise Weizsäcker (1898–1976), psychotherapist

-

Heinrich Weizsäcker (1862–1945), professor of art history; ⚭ Sophie Kästner (1862–1959)

- Agnes Weizsäcker (1896–1990), ⚭ Hermann Holthusen (1886–1971), radiologist

- Karl Hermann Wilhelm Weizsäcker (1898–1918)

- Bertha Weizsäcker (1864–1945), ⚭ Karl von Müller (1852–1940), theologian

- Julius Hugo Wilhelm Weizsäcker (1861–1939), lawyer; ⚭ Julie Stölzel (1861–1944)

- (I) Carl Friedrich Gottlob Weizsäcker (1774–1835), City School of Öhringen; ⚭ Johanna Rosalie Friederike Bratz (1789–1860)

Other lines

- Theodor von Weizsäcker (1830–1911), Württemberg postal president; Awarded staff nobility in 1880

- Wilhelm von Weizsäcker (1820–1903), district judge in Öhringen; Awarded staff nobility in 1895

- Paul Weizsäcker (1850–1917), high school teacher, classical philologist and classical archaeologist

- Theodor Weizsäcker (1860–1916), doctor

- Wilhelm Weizsäcker (1886–1961), National Socialist legal historian and administrative director of the " Reinhard Heydrich Foundation" (Prague branch of the Weizsäcker)

literature

- Hans-Joachim Noack : The Weizsäcker. A German Family , Siedler-Verlag, September 2019, ISBN 978-3-8275-0079-3

- Hans Cappel: On the history of the Woogsacker mill, Niederbexbach . In: Saarpfalz 26, 4, 2008, ISSN 0930-1011 , p. 62 f., (Location in the IRB library: IRB Z 17 11).

- Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels , Adelslexikon Volume XVI, pp. 51-52, Volume 137 of the complete series, CA Starke Verlag, Limburg (Lahn) 2005, ISSN 0435-2408

- Friedrich Wilhelm Euler : pedigree v. Weizsäcker - v. Graevenitz. Exemplary representation of the prosopographical requirements and consequences of an all-German leadership group. In: Herold Studies, Volume 1, published by Herold zu Berlin, Verlag des Herold zu Berlin 1992.

- Martin Wein : The Weizsäcker - History of a German Family . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-426-02417-9 .

- Same, Freiherrliche Häuser B Volume VI, Volume 62 Complete Series, Limburg (Lahn) 1976, p. 446 ff.

- Same, Freiherrliche Häuser B Volume I, Volume 7 Complete Series, Limburg (Lahn) 1954, p. 461 ff.

References and comments

- ↑ The only two different spellings of the twelve flowering lines into which the sex is divided today - in the past, up to the beginning of the 19th century, in the most varied of imaginable variants

- ↑ Cf. Genealogical Handbook of the Adels , Freiherrliche Häuser Vol. VI, Vol. 62 of the complete series, Limburg (Lahn) 1976, p. 446

- ^ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels , Adelslexikon Volume XVI, pp. 51-52, Volume 137 of the complete series, CA Starke Verlag, Limburg (Lahn) 2005, ISSN 0435-2408

- ↑ Martin Wein: The Weizsäcker

- ^ Günter Bayerl : Müller . In: Reinhold Reith (Hrsg.): Lexikon des alten Handwerks. From the late Middle Ages to the 20th century , Munich 1990, p. 171

- ↑ Wolfgang von Hippel: Poverty, lower classes, marginalized groups in the early modern times , Volume 34 of Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte, 1995, p. 36f

- ^ A b Johannes Mager, Günter Meissner, Wolfgang Orf: The cultural history of the mills . 1989, pp. 154f

- ^ Martina Reiling: Population and social topography of Freiburg i. Br. In the 17th and 18th centuries: families, trades and social status . Volume 24 of the publications from the archive of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, 1989, p. 102 "Müller was considered dishonest in many places and for a long time beyond the Middle Ages".

- ↑ The - usually several - mouth cooks were subordinate to the master chef. Ernst von Malortie: The court marshal: manual for the establishment and management of a court . 1846, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Martin Wein: Die Weizsäcker , p. 52

- ^ Ralph Giordano : Weizsäcker and other Germans . In: Der Spiegel . No. 11 , 1989, pp. 63 ( online ).

- ↑ Richard von Weizsäcker: Four times. Memories , Berlin 1997, p. 29: “Gradually a family of pastors and scientists, officials and politicians developed. It was done without inheriting titles, farms or assets. Each generation had its own place to buy. The decisive factor remains the individual qualification, according to the rules of the emerging civil society, which contrasts the elite with the elite of the birth. "

- ↑ Günter Hofmann, Richard von Weizsäcker: Ein deutsches Leben , 2010, p. 28: "A family that gained a reputation and wanted to have a say, in Öhringen, Tübingen, Stuttgart and beyond Stuttgart."

- ↑ Hofmann, p. 29: "The basis was now secured: the family no longer had to struggle for advancement, they belonged to the bourgeois elite."

- ↑ Leonidas Hill (ed.), The Weizsäcker Papers 1933–1950 , Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Vienna 1974, Volume 2, p. 70: At the end of March 1933, Ernst von Weizsäcker came to the “simple truth” that “this regime must not throw it over. ... You have to give him all the help and experience and ensure that the second stage of the new revolution that is now beginning is a seriously constructive one. "

- ↑ Weizsäcker Papers, Volume 2, p. 100: Ernst von Weizsäcker 1936 on the provisional assignment of the Political Department of the Foreign Office “..., try to expand my radius of action as much as possible and have a program. What more could you want at 54 ... "

- ↑ Weizsäcker Papers, Volume 2, p. 125 (note dated April 3, 1938), Ernst von Weizsäcker noted after his appointment as State Secretary in the Foreign Office, “I commemorate Karl's birthday today in a kind of legacy mood. Without his precedence in the Foreign Office, I would probably never have come to this house. He filled his place there. For me the exam is just coming. "

- ↑ A WEAPONSHOUSE? NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND REACTOR RESEARCH AT THE KAISER-WILHELM-INSTITUT FOR PHYSICS p. 39 (PDF)

- ↑ ibid. P. 40

- ↑ Udo Benzenhöfer: The medical philosopher Viktor von Weizsäcker. An overview of life and work. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 171 .

- ↑ Extract from the Farm Hall transcript. Retrieved May 21, 2016 .

- ^ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels , Adelslexikon Volume XVI, pp. 51-52, Volume 137 of the complete series, CA Starke Verlag, Limburg (Lahn) 2005, ISSN 0435-2408

- ↑ Andreas Borcholte: Abgehört: The most important music of the week. In: Spiegel Online . March 24, 2015, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ www.kulturimpuls.org Käthe Weizsäcker , accessed on January 31, 2017.

- ↑ Agnes Holthusen b. Weizsäcker , in: Hamburg Women's Biographies, October 18, 2016

- ↑ Martin Wein, p. 18