Wiesche mine

| Wiesche mine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

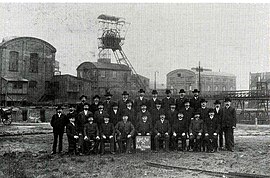

| The Wiesche colliery - presumably during the owners' meeting - on a photograph from 1904 | |||

| other names | Wiescher tunnel | ||

| Funding / year | Max. 596,903 t | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Employees | up to 1593 | ||

| Start of operation | 1700 | ||

| End of operation | 1952 | ||

| Successor use | Rosenblumendelle colliery / Wiesche | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Hard coal | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 51 ° 26 '13.1 " N , 6 ° 55' 9.9" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Be called | ||

| local community | Mülheim an der Ruhr | ||

| Independent city ( NUTS3 ) | Mülheim an der Ruhr | ||

| country | State of North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

| District | Ruhr area | ||

The Wiesche colliery was a hard coal mine in Mülheim an der Ruhr , in the district of Heißen . The name of the mine is derived from the dialectal form of meadow. The mine was also known as Wiescher Stolln . The mine was part of the Broich dominion . The Wiesche colliery was one of the most important mines in the Düsseldorf administrative district in the second half of the 19th century.

history

The beginnings

Already before the year 1700 the mine In der Wieschen (later Wiesche) was mining coal in the tunnel . The area of today's Buggenbeck was dismantled. In the period between the end of the 17th century and 1730, the colliery operated a mine tunnel to the Ruhr together with the Leybank and Sellerbecker Stolln collieries . The exposed coal reserves were partly extracted in the substation . There were up to six dies . These dies were sunk to a depth of several tons and had a depth of 62 meters. In 1779, in cooperation with the Kinderberg and Schökenbank collieries, further coal reserves were sought. In 1796 a new field was mortgaged. The mine was closed in the same year. Now that the supplies above the bottom of the tunnel were running low, the coal could only be extracted at high cost. For this reason the transition to civil engineering was planned .

Transition to civil engineering

In 1809 the mine was put back into operation and the transition to civil engineering began. From this time on the mine was also called Zeche Wiesche Tiefbau. In the same year, the sinking work began for the "Friedrich" machine shaft . At a depth of 16 meters, the shaft reached the carbon . Around the pit water from the deep workings to lift one was dewatering machine needed. The machine was built by Johann Dinnendahl and was put into operation the following year. However, the performance of this machine turned out to be insufficient. The bottom of the tunnel was at a depth of 19.5 puddles , the first 1st underground level was at 47 puddles. From 1811, the coal in the Friedrich shaft was extracted using horse pegs . The transport for days took place over a sliding path. This path was 1065 Lachtern long and reached as far as the city of Mülheim. In 1813 a 48-inch steam engine was put into operation. This machine was also built by Johann Dinnendahl. That year the mine was in production . The trades of the Wiesche colliery transferred the management of the mine to Johann Dinnendahl. In 1814 work began on lowering the “Wilhelmine” shaft in order to open up further seam sections . In 1816 the Wilhelmine shaft was put into operation up to the first level. The first level was at a depth of 136 meters. The shaft was equipped with a steam-powered hoisting machine . The machine had a standing cylinder with a diameter of 470 millimeters and had an output of eleven hp . The machine was built by the Dinnendahl company.

In 1817 a new steam engine for drainage was installed. In 1821 the Friedrich and Wilhelmine shafts were in operation. The Friedrich shaft was in operation as a production shaft and Wilhelmine shaft as a drainage shaft. In 1828 the colliery began with the excavation (construction) of the Wiescher Erbstollen. Since this was too far away for the delivery to the delivery shaft due to the overgrown mine building , it was necessary to create a third shaft. The sinking work for the Emilie shaft began in 1822. The shaft was on the north side of the saddle set . This year the Wiesche colliery was the largest colliery in the Ruhr area, producing 130 tons of hard coal per day . In 1829 the first level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 139 meters (-31 m above sea level ). The second level was set at a depth of 169 meters (-61 m above sea level). In 1830 the shaft went into production up to the second level. In the years that followed, the Wiesche colliery was one of the largest collieries in the Ruhr area. In 1833 a new water retention steam engine was commissioned from the ironworks in Mülheim. This machine was put into operation at the Friedrich shaft in 1836. The machine pumped the pit water from a depth of 170 meters. In 1837 the mine was by the Wiescher Erbstollen solved . The water was raised in the Friedrich shaft to the bottom of the Erbstollen and then drained off via the Erbstollen . In the following years, a horse-drawn tram was built to facilitate the promotion of the main routes. Pit horses were used for the extraction , which brought the carts to the filling point .

The further operation

In 1840 work began on digging the Emilie shaft deeper. The following year, the third level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 192 meters (-54 m above sea level). In 1842 the trades of the Wiesche colliery tried to consolidate with the Leybank colliery . The Leybank colliery bordered the northern divide of Wiesche. However, this union and the further expansion of the mine was associated with high costs. In order to realize the consolidation, the sinking work for the Union shaft began in the same year. The shaft was sunk to the 63 level. In the same year Schacht Emilie was connected to the Sellerbeck Railway. In 1843 the 4th level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 236 meters (-128 m above sea level). The Längenfeld Wiesche was awarded on March 14, 1844 . From the year Broich was very heavily in debt and the creditors pushed for a satisfactory solution. In the following years in particular, this led to a change in the old mining law and thus to a replacement of the “Broich private tithe” . In 1846 Schacht Vereinigung was transferred to the Zeche Verein . Around 1850 the mine was also called the Wische colliery. In 1850 the Wiesche colliery consolidated with several mines and pit fields.

Merging of the mines

After the consolidation the mine was renamed to Zeche Vereinigte Wiesche. On October 18, 1854, Broich's tithe right was sold by the Broich lordship to the private Mülheim ten company. The trades of the United Wiesche colliery bought themselves free from this obligation in the following years. In 1855, the third level was set in the Friedrich shaft at a depth of 207 meters. In addition, a breakthrough was made with the Emilie shaft. In the following year, the sinking work in the Emilie shaft continued. In 1857 the 5th level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 303 meters (- 195 m above sea level). In 1859 the mining of the shaft association was stopped, the construction field fell to shaft Emilie. In 1860, the Emilie shaft was used as a weather shaft. On June 1 of the same year there was an inrush of standing water, in which three miners were killed. In 1862, the 6th level and a depth of 332 meters (- 224 m above sea level) a midsole was added in the substation construction at a depth of 320 meters (- 212 m above sea level). From 1861, experiments were carried out at the mine to briquette coal and coal dust with and without binding agents. In the same year, the first briquette factory in the Ruhr area for the production of briquettes for domestic use was put into operation. In addition, the takeover of the Jean Paul colliery was confirmed by the mining authorities . At that time, the mine belonged to the Dortmund Upper Mining District and there to the Mülheim mining area . In 1863 the cable car was set up in the Emilie shaft . In the following year, the Emilie shaft was sunk down to the 6th level. In 1866 the Geviertfeld Richter was awarded.

In 1867 the attempts to manufacture briquettes were stopped again. The briquette factory was shut down in the same year for cost reasons. In 1870 the four shafts Leybank, Friedrich, Vereinigung and Emilie were in operation. In 1875 the sinking work for the “Velau” shaft (shaft 3) began. The shaft was in the North Field at today Reuterstraße set . In the same year the shaft reached the carbon at a depth of 45 meters. In 1876 the 7th level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 382 meters (- 274 m above sea level). In the same year the district fields Wiesche IV and Wiesche V were awarded. In 1878 the 7th level was set in the Emilie shaft at a depth of 432 meters (-324 m above sea level). Moreover, that was headframe of wood replaced by a masonry shaft tower. In 1879 the shaft association was closed and abandoned. In the following year, the Friedrich shaft and the Leybank shaft were closed. Both shafts were later dropped and filled . In 1887 a new briquette factory was put into operation. On August 13, 1888, there was a flood. Due to this water ingress, the 8th level sank and had to be swamped . In the following year, the necessary swamping work was carried out and the bottom cleared . In 1895, the sinking work for weather shaft 4, which took several tons, began. The shaft was set in the Good Hauser trough and first 44 meters Seiger geteuft. Then a 600 meter long cut was made. On May 14 of the same year there was a firedamp explosion in the mine , in which three miners lost their lives. In 1896, the sinking work for shaft 2 began. The shaft was set up 100 meters from the Emilie shaft. At a depth of 16 meters, shaft 2 reached the Carboniferous. On July 1st of the same year the briquette factory was shut down. In 1897, shaft 2 was penetrated with the 8th level. In the same year, the Geviertfeld Fuchs was awarded. The Berechtsame included at this time four length fields and five square fields, the area of the mining area was 5.5 km 2 . In 1898 there was a change of ownership and another renaming. Mathias Stinnes became the head of the mine .

Operation after renaming

After being renamed to Zeche Wiesche, the mine was still in operation. The new owner of the mine was the Mülheimer Bergwerks-Verein . In 1899 a new chew opened . In the same year repairs were carried out on shaft 1. In 1900 a carbon copy was made with the Rosenblumendelle colliery . The excavation took place below the 8th level with the aid of a die. On April 1st of the same year the briquette factory was put back into operation. In 1901 there was a water ingress in the southern field. A weather shaft was in operation in the northern field. At that time, the Anna Gertraud field belonged to the mine field. On April 1, 1902, the briquette factory was shut down again. The Emilie shaft (shaft 1) was equipped with a steel headframe. After the renovation, shaft 1 went back into operation the following year. On January 1st, 1904, the briquette factory was put back into operation. In the same year, the 9th level was set in the blind shaft at a depth of 552 meters (- 444 m above sea level). In 1905, the sinking work in shaft 2 was resumed.

In 1906 a carbon copy was made with the Humboldt colliery. Part of the field was handed over to the Humboldt colliery in the same year. In 1909 the fields Roland and Sellerbeck were taken over. The entire right now covered an area of 13.8 km 2 . In 1910 exploration work began in the Sellerbeck field. On February 15, 1913, a cage crashed, killing four miners. In 1914, a break was made in the Emilie shaft from the 9th level . From 1915 the Emilie shaft was in operation up to the 9th level. On June 16, 1916, standing water ingress occurred on the 6th level in the Sellerbeck field. The subsequent swamp work on the 9th level took two and a half months. In 1920 the weather shafts 3 and 4 were abandoned, the Emilie shaft became a weather shaft. In 1929 a carbon copy was made with the Humboldt field of the Rosenblumendelle colliery. In 1930, the production was taken over from the Humboldt field.

The last few years until the Verbund

In 1931 the Humboldt field was taken over by the Rosenblumendelle colliery. The Franz shaft was located in the field; the 5th level was at a depth of 521 meters. The field has now been further opened up from the Wiesche colliery. On June 25, 1937, three miners were killed by toxic gases in the Humboldt field. In 1938, the 10th level was set in shaft 2 at a depth of 750 meters (- 642 m above sea level). In 1946, the 10th level became the main extraction level. In 1949, mining in the Sellerbeck field was stopped. The Christian weather shaft was dropped and filled. In 1951 a new carbon copy was created with the Rosenblumendelle colliery. On January 1, 1952, the association with the Rosenblumendelle colliery was established under the name Rosenblumendelle / Wiesche. After a central briquette factory had previously been built, the briquette factory of the Wiesche colliery was shut down.

Promotion and workforce

The first known workforce dates from 1811, when 151 miners were employed in the mine. The first funding figures are from 1817, this year 180,000 were ringed coal promoted. In 1835, 282 people were employed at the mine. In 1838, 290 employees produced 816,450 bushels of hard coal. The coals extracted from the mine were good lean coals. The coals were of high quality and were used as brick coals. In 1840, the production was around 43,000 tons of hard coal. In 1846, 51,574 tons of hard coal were mined. In 1850 165,537 Prussian tons of hard coal were mined with 320 employees . In 1853, 57,068 tons of hard coal were mined and the workforce was 331. In 1855 76,635 tons of hard coal were mined with 412 employees. In 1860, 38,667 tons of hard coal were mined, the workforce was 303 employees. In 1865, 397 employees produced 63,122 tons of hard coal. In 1870, 85,918 tons of hard coal were mined, the workforce was 413 employees. In 1880, with 306 employees, 93,651 tons of hard coal were mined. In 1890, 94,378 tons of hard coal were mined with 411 employees. In 1896, the production was 126,000 tons of hard coal.

In 1900 283,331 tons of hard coal were mined, the workforce was 1039 employees. In 1905, with 956 employees, 249,406 tons of hard coal were mined. In 1910, the production was 331,081 tons, the workforce was 1134 employees. In 1913 around 330,000 tons of hard coal were mined with 1,073 employees. In 1915, the production was 222,261 tons of hard coal, the workforce was 793 employees. In 1920, 236,000 tons of hard coal were mined, the workforce was 1240 employees. In 1925, with 879 employees, 281,379 tons of hard coal were mined. In 1930 the production was 466,773 tons of hard coal, the workforce was 869 employees. In 1935 the half-million-ton mark was exceeded for the first time. This year, around 535,000 tons of hard coal were mined with 1121 employees. In 1937, 596,903 tons of hard coal were produced in the mine, this was the maximum production of the mine. The workforce this year was 1455 employees. In 1940, 1,389 employees produced 472,242 tons of hard coal. In 1945 the production sank to 115,960 tons of hard coal, the workforce in that year was 936 employees. The last known production and workforce figures for the mine are from 1950. In that year, 388,174 tons of hard coal were extracted with 1593 employees.

Current condition

The nursery building of the Wiesche colliery is still preserved today.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Joachim Huske : The coal mines in the Ruhr area. Data and facts from the beginning to 2005 (= publications from the German Mining Museum Bochum 144) 3rd revised and expanded edition. Self-published by the German Mining Museum, Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-937203-24-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wilhelm Hermann, Gertrude Hermann: The old collieries on the Ruhr. 4th edition. Publishing house Karl Robert Langewiesche, successor Hans Köster, Königstein i. Taunus 1994, ISBN 3-7845-6992-7 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Hermann Adam Von Kamp: The castle and the rule Broich. 1st part, published by Joh.Ewich, Duisburg 1852

- ↑ a b H. Fleck, E. Hartwig: History, statistics and technology of coal in Germany and other countries in Europe . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1865

- ↑ Kammerer-Charlottenburg: The technology of load handling then and now. Study of the development of hoisting machines and their influence on economic life and cultural history, printing and publishing by R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin.

- ↑ Kurt Pfläging : The cradle of Ruhr coal mining. Verlag Glückauf GmbH, 4th edition, Essen 1987, ISBN 3-7739-0490-8 .

- ↑ a b Joachim Huske: The hard coal mining in the Ruhr area from its beginnings to the year 2000. 2nd edition. Regio-Verlag Peter Voß, Werne 2001, ISBN 3-929158-12-4 .

- ^ A b c Gerhard Gebhardt: Ruhr mining. History, structure and interdependence of its societies and organizations. Verlag Glückauf GmbH, Essen 1957

- ↑ The coal of the Ruhr area . Compilation of the most important mines in the Ruhr coal mining area, specifying the quality of the coal mined, the rail connections, as well as the mining and freight rates. Second completely revised and completed edition, publishing bookstore of the M. DuMont-Schauberg'schen Buchhandlung, Cologne 1874

- ↑ Early mining on the Ruhr: Zeche Wiesche (accessed on March 22, 2013)

Web links

- Early mining on the Ruhr: Historical map around 1840 (accessed on March 22, 2013)

- Early mining on the Ruhr: Map of the situation around 2000 (accessed on March 22, 2013)