Symphony No. 6 (Mahler)

The Symphony No. 6 in A minor by Gustav Mahler, sometimes referred to as the Tragische ('Tragic'), was composed between 1903 and 1904 (rev. 1906; scoring repeatedly revised). The work's first performance was in Essen, on May 27, 1906, conducted by the composer.

The work is unique among Mahler's symphonies in ending in an unambiguously tragic manner. Mahler is, of course, widely felt to be a 'tragic' composer – and yet the fact is that most of his symphonies end triumphantly (Nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8), while others end in a mood of contentment (No. 4), or quiet resignation (No. 9), or radiant calm (No. 10). The tragic, even nihilistic ending of No. 6 has in fact been seen as particularly unexpected, given that the symphony was composed at what was apparently an exceptionally happy time in Mahler's life: he had married Alma Schindler in 1902, and during the course of the work's composition his second daughter was born.

Perhaps because of its complexity or because of its grim overall mood and its shatteringly pessimistic if often exhilarating outcome, the symphony is not the most popular Mahler symphony amongst 'general' listeners. However, the work is reckoned by many to be one of his finest, and is thought to be most highly regarded by musicians themselves. Both Alban Berg and Anton Webern praised it when they first heard it: for Berg it was "the only sixth, despite the 'Pastoral'"; while Webern actually conducted it on more than one occasion.

The status of the work's nickname is problematic. The programme for the work's first Vienna performance (January 4, 1907) shows the subtitle Tragische, but this word is not found on the programme for the earlier performance in Munich on November 8, 1906. Nor does the word Tragische appear on any of the scores that C.F. Kahnt published (first edition, 1906; revised edition, 1906), or in Richard Specht's officially approved 'thematic analysis', or on Alexander Zemlinsky's piano duet transcription (1906). In his Gustav Mahler memoir, Bruno Walter claimed that "Mahler called [the work] his Tragic Symphony", and this is often cited in support of a nickname that many people clearly find congenial. The fact remains, however, that Mahler did not so title the symphony when he composed it; when he first performed it; when he published it; when he allowed Specht to analyse it; or when he allowed Zemlinsky to arrange it. He had, moreover, decisively rejected and disavowed the titles (and programmes) of his earlier symphonies by 1900; and neither the 'Lied der Nacht' subtitle of the Seventh Symphony, nor the 'Sinfonie der Tausend' of the Eighth, stem from Mahler. For all these reasons, the Tragische nickname is not used in serious works of reference.

Instrumentation

The symphony is written for a large orchestra comprising:

- Woodwinds

- Piccolo

- 4 Flutes (3rd & 4th doubling Piccolos)

- 4 Oboes (3rd & 4th doubling English Horns)

- English Horn

- 3 Clarinets in A, B-flat, and C

- Clarinet in D and E-flat

- Bass Clarinet in A and B-flat

- 4 Bassoons

- Contrabassoon

- Percussion

- (see note below)

- 4 Timpani (2 players)

- Bass drum (also played with rute)

- Snare drum

- Cymbals, both crash and suspended

- Tam-tam

- Glockenspiel

- Xylophone

- 2 or more deep Bells of deep sound and indeterminate pitch, placed off-stage

- Cowbells, used both on- and off-stage

- Triangle

- Hammer

As in several other of his compositions, Mahler indicates in several places that extra instruments should be added, including two or more celestas "if possible," "several" triangles at the end of the first movement, doubled snare drum (side drum) in certain passages, and in one place in the fourth movement "several" cymbals. While at the beginning of each movement Mahler calls for 2 harps, at one point in the Andante he calls for "several," and at one point in the Scherzo he writes "4 harps." Often he does not specify a set number, especially in the last movement, simply writing "harps."

While the first version of the score (currently available from Dover Publications) included slapstick and tambourine, these were removed over the course of Mahler's extensive revisions.

Unlike Mahler's second, third, fourth, and eighth symphonies, there are no vocal forces.

The sound of the hammer, which features in the last movement, was stipulated by Mahler to be "brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an ax)." The sound achieved in the premiere did not quite carry far enough from the stage, and indeed the problem of achieving the proper volume while still remaining dull in resonance remains a challenge to the modern orchestra. Various methods of producing the sound have involved a wooden mallet striking a wooden surface, a sledgehammer striking a wooden box, or a particularly large bass drum, or sometimes simultaneous use of more than one of these methods.

Structure

The work is in four movements:

- Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.

- Andante moderato (see below)

- Scherzo: Wuchtig (see below)

- Finale: Sostenuto - Allegro moderato - Allegro energico

The duration is around 80 minutes.

History

There is some controversy over the order of the two middle movements, though recent research has clarified the issue considerably. Mahler is known to have conceived the work as having the scherzo second and the slow movement third, a somewhat unclassical arrangement adumbrated in such earlier gargantuan symphonies as Beethoven's Ninth and Bruckner's Eighth and (unfinished) Ninth, as well as in Mahler's own four-movement First and Fourth. It was in this arrangement that the symphony was completed (in 1904) and published (in March 1906); and it was with a conducting score in which the scherzo preceded the slow movement that Mahler began rehearsals for the work's first performance, in May 1906. During those rehearsals, however, Mahler decided that the slow movement should precede the scherzo, and he instructed his publishers C.F. Kahnt to prepare a 'second edition' of the work with the movements in that order, and meanwhile to insert 'errata' slips indicating the change of order into all unsold copies of the existing edition. The 'seriousness' of such a decision is not to be under-estimated: as Jeffrey Gantz has pointed out, "A composer who premières his symphony Andante/Scherzo immediately after publishing it Scherzo/Andante can expect a degree of public ridicule, and [the reviewer of the first Vienna performance] didn't spare the sarcasm". Moreover, this revised, 'second thoughts' ordering was observed by Mahler in every single performance he gave; it is also how the symphony was performed by others during his lifetime.

The first occasion on which the abandoned, original movement order was reverted to seems to have been in 1919, after Alma had sent a telegram to Willem Mengelberg which said "First Scherzo, then Andante". Mengelberg, who had been in close touch with Mahler until the latter's death, and had happily conducted the symphony in the 'Andante/Scherzo' arrangement right up to 1916, then switched to the 'Scherzo/Andante' order. In this he seems to have been alone: other conductors, such as Oskar Fried and Dimitri Mitropoulos, continued to perform (and eventually record) the work as 'Andante/Scherzo', as per Mahler's own second edition, right up to the early 1960s.

In 1963, however, Erwin Ratz's 'Critical Edition' of the Sixth appeared, and in this the Scherzo preceded the Andante. Ratz, however, never offered any support (he did not even cite Alma's telegram) for his assertion that Mahler 'changed his mind a second time' at some point before his death; but his editorial decision was questioned by few musicians – and even those who did not accept his 'third thoughts' ordering (such as Barbirolli in his acclaimed 1967 recording) could find that their 'Andante/Scherzo' performance would be changed by the record company to 'Scherzo/Andante' so as to make their recording agree with the 'Critical Edition'. The utter lack of documentary or other evidence in support of Ratz's (and Alma's) 'reverted' ordering has caused the most recent Critical Edition to restore the 'Andante/Scherzo' order; however, so many conductors and orchestras still possess materials (and prejudices) which place the Scherzo before the Andante that the work is regularly performed with the movements in that order. The matter remains hotly debated, however.[1][2]

Formally, the symphony is one of Mahler's most outwardly conventional. The form and character of each individual movement are also quite traditional, with a fairly standard sonata form first movement (which even includes an exact repeat of the exposition, most unusual in Mahler), leading to the middle movements, one slow, the other a scherzo, and the finale, also in sonata form, quicker and recapping some previously heard material.

Recorded and performed movement order

Recorded and performed examples on the inner movements' order by several prominent conductors.[3]

Composition

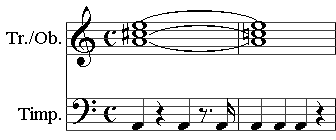

The first movement, which for the most part has the character of a march, features a motif consisting of an A major triad turning to A minor over a distinctive timpani rhythm (the chords are played by trumpets and oboes when first heard):

This motif, which some commentators have linked with fate, reappears in subsequent movements. The first movement also features a soaring melody which the composer's wife, Alma Mahler, claimed was representative of her; this melody is now often known as the "Alma theme". The movement's end marks the happiest point of the symphony with a restatement of the Alma theme.

The andante is a respite from the brutal intensity of the rest of the work. Its main theme is an introspective ten-bar phrase that is technically in E-flat major, though the theme alone can seem major and minor at once. The orchestration is more delicate and reserved in this movement, making it all the more poignant when compared to the driving darkness of the other three.

The scherzo marks a return to the unrelenting march rhythms of the first movement, though in a 'triple-time' metrical context. Its trio (the middle section), marked Altväterisch ('old-fashioned'), is rhythmically irregular (4/8 switching to 3/8 and 3/4) and of a somewhat gentler character. Alma's report, often repeated, that in this movement Mahler "represented the unrhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zigzags over the sand" is refuted by the chronology: the movement was composed in the Summer of 1903, when Maria Anna Mahler (born November 1902) was less than a year old, and when Anna Justine (born July 1904) had not even been conceived. All the same, it is widely accepted by contemporary interpretors and conductors and it is usually in this playful-turned-terror-filled manner that this movement is conducted.

The last movement is an extended sonata form, characterized by drastic changes in mood and tempo, the sudden change of glorious soaring melody to deep pounded agony. Apparently in this movement Mahler was attempting to confront the fear of his own artistic downfall; as in the Kindertotenlieder, he chose to deal with his concern by addressing it directly. The movement is punctuated by three hammer blows. Alma quotes her husband as saying that these were three mighty blows of fate befallen by the hero, "the third of which fells him like a tree". She identified these blows with three later events in Gustav Mahler's own life: the death of his eldest daughter Maria Anna Mahler, the diagnosis of an eventually fatal heart condition, and his forced resignation from the Vienna Opera and departure from Vienna. When he revised the work, Mahler removed the last of these three blows for structural reasons, though some modern performances restore it. The piece ends with the same rhythmic motif that first appeared in the first movement, but the chord above it is a simple A minor triad, rather than A major turning into A minor.

Quotations

My sixth will propound riddles the solution of which may be attempted only by a generation which has absorbed and truly digested my first five symphonies.

- (Mahler, in a letter to Richard Specht).

The only Sixth, despite the 'Pastoral'.

- (Alban Berg, in a letter to Anton Webern).

Premieres

- World premiere: May 27, 1906, Essen, conducted by the composer.

- American premiere: December 11, 1947, New York City, conducted by Dimitris Mitropoulos.

References

- ^ http://www.mahlerfest.org/mfXVI/notes_myth_reality.htm Mahlerfest - Symphony No. 6 - Myth and Reality explores in some detail the controversy surrounding the movement order

- ^ http://www.andante.com/profiles/Mahler/symph6.cfm Extensive history and analysis by renowned Mahler scholar Henry Louis de La Grange

- ^ http://mahlerarchives.net/archives/wagnerM6.pdf Naturlaut Vol. 4 No. 4

- ^ Barbirolli's 1967 recording was re-ordered as Scherzo-Andante in the original recordings

- ^ originally performed the work Scherzo-Andante

- ^ originally performed the work Scherzo-Andante

- ^ originally performed the work Andante-Scherzo

- ^ made the first recording of the 6th, with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra

External links

- Free scores by Symphony No. 6 at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Synoptic survey: Extensive critical analysis of many recordings by Tony Duggan