Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was a British novelist, short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, travel writer, and editor of the works of her husband, Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley. She was the daughter of the political philosopher William Godwin and the writer, philosopher, and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary Shelley is best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818).

After the death of Mary Wollstonecraft eleven days after her daughter's birth, Mary Godwin was brought up, along with her older sister Fanny Imlay, by William Godwin. When she was three, he married his neighbour, Mary Jane Clairmont. Mary Godwin received a rich, if informal, education under William Godwin, who brought her up to believe in his liberal political theories, including republicanism, radicalism, and the perfectibility of man.

In 1814, Mary Godwin fell in love with the married philosopher-poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, one of William Godwin's political followers. That summer, despite her father's disapproval, the couple eloped to France, along with Mary's step-sister, Claire Clairmont. The three travelled through France to Switzerland and returned along the Rhine, by which time Mary Godwin was clearly pregnant. Over the next two years, the couple was ostracized, in constant debt, and lost their prematurely born daughter. They married in late 1816 after the suicide of Percy Shelley's first wife.

In 1817, they spent a famous summer with Lord Byron, John William Polidori, and Claire Clairmont near Geneva, Switzerland, where Mary conceived the idea for her novel Frankenstein. In 1818, the Shelleys left Britain for Italy, where their second and third child died before Mary Shelley gave birth to her last and only surviving child, Percy Florence. In 1822, Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned when his sailing boat sank during a storm in the Bay of Spezia. A year later, Mary Shelley returned to England. Though she had offers, she never remarried. Instead, she devoted herself to the upbringing of her son and a career as a professional author. The death of her father-in-law in 1844 left her financially comfortable for the first time in her life, but her last decade was dogged by illness, probably caused by the brain tumour that killed her at the age of 53.

Until the 1970s, Mary Shelley was principally known for her novel Frankenstein, which remains widely read and has inspired many theatrical and film adaptations. Mary Shelley's notes to her 1839 edition of Percy Shelley's poems have also remained in print, though she has often been accused of censoring her husband's poems to soften their radicalism or atheism. Recent decades have brought a reassessment of Mary Shelley's later political views, however, and a more comprehensive view of her achievement as a whole. Her novel Matilda, written in 1819 and 1820 and published for the first time in 1959, has become perhaps her second most popular novel.[2] Scholars have recently shown increasing interest in Mary Shelley's literary output, particularly her novels, which include Valperga (1823), The Last Man (1826), Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), and Falkner (1837). Scrutiny of Mary Shelley's later works has challenged the view that their author became conservative in her later years and abandoned the political ideals she once shared with her father and husband.[3] Lesser-known works such as the travel book Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844) and the rediscovered biographical articles for Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1836–39) show that Mary Shelley remained a political radical.

Biography

Early life

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers Town, London in 1797. She was the second child of the feminist philosopher, educator, and writer Mary Wollstonecraft and the first child of the philosopher, novelist, and journalist William Godwin. Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever ten days after Mary was born; and Godwin was left to raise Mary, along with her older half-sister, Fanny Imlay, Wollstonecraft's child by the American speculator Gilbert Imlay.[4] A year after Wollstonecraft's death, Godwin published what he felt were sincere, open, and compassionate Memoirs (1798) of her. However, because he revealed her affairs and her illegitimate child, they were seen as shocking and in poor taste. Wollstonecraft, who had been praised while alive, was branded a "whore" after death because of Godwin's book. Mary Godwin read these Memoirs as a teenager and knew of the scandal attached to her parents, but as a child, according to Seymour, she only knew the loving image presented to her by her family.[5]

The letters of Louisa Jones, whom Godwin employed as housekeeper and nurse, suggest that Mary's earliest years were happy ones.[6] Godwin knew he could not raise his daughters by himself and had been casting about for a second wife.[7] In December 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont, a well-educated woman with two young children of her own—Charles and Claire—and let Louisa go.[8] Disliked by most of Godwin’s friends, the new Mrs Godwin was quick-tempered and quarrelled frequently with her husband;[9] but the marriage was a success.[10] Mary Godwin came to detest her stepmother,[11] who Godwin's 19th-century biographer C. Kegan Paul later suggested had favoured her own children over Mary Wollstonecraft’s.[12]

Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects; he often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the former vice-president of the United States, Aaron Burr.[13] Godwin admitted he was not educating the children according to Mary Wollstonecraft's philosophy, but under the direction of his wife, Mary Godwin nonetheless received an unusual and advanced education for a girl of the time. She had a governess, a daily tutor, and read many of her father's children's books on Roman and Greek history in manuscript.[14] When she was fifteen, Godwin described her as "singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible".[15]

In June 1812, William Godwin sent Mary to stay with the family of the radical William Baxter, near Dundee, Scotland,[16] to whom he wrote, "I am anxious that she should be brought up . . . like a philosopher, even like a cynic".[17] Scholars have only speculated as to why she was sent, postulating that it was for her health, to remove her from the seamy side of business, or to introduce her to radical politics.[18] Mary Godwin revelled in the spacious surroundings of Baxter's house and in the companionship of his four daughters, and she returned in the summer of 1813 for a further stay of ten months.[19] It was here that she believed she became an author, writing in the 1831 introduction to Frankenstein: "I wrote then—but in a most common-place style. It was beneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, that my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered."[20]

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet-philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Harriet in the interval between her two stays in Scotland.[22] By the time she returned home for a second time on 30 March 1814, Percy Shelley had become estranged from his wife and was regularly visiting Godwin, whom he had agreed to bail out of debt.[23] Mary and Percy began meeting each other secretly at Mary Wollstonecraft's grave in St Pancras Churchyard: and they fell in love—she was nearly seventeen, he nearly twenty-two.[24] To Mary's dismay, Godwin disapproved and did all he could to thwart the relationship and salvage the "spotless fame" of his daughter.[25] Mary, who later wrote of "my excessive and romantic attachment to my father", [26] was confused. She saw Percy Shelley as an embodiment of her parents' liberal and reformist ideas of the 1790s, particularly Godwin's opposition to the repressive monopoly of marriage (espoused in the 1793 Political Justice but since retracted).[27] On 28 July 1814, the couple eloped to France, taking Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, with them.[28]

After convincing Mrs Godwin, who had pursued them to Calais, that they did not want to return, the trio travelled to Paris and then, by donkey, mule, and carriage, through a France recently ravaged by war, to Switzerland. “It was acting in a novel,” Mary Shelley recalled in 1826, “being an incarnate romance”.[29] They were often short of money, though Percy Shelley sold possessions and arranged loans along the way. He and Mary read works by Mary Wollstonecraft and others, kept a joint journal, and continued their own writing.[30] Despite its hardships, the adventure was sustained by youthful love and at times assumed the character of an idyll (at least for Mary and Percy). At Lucerne, lack of money forced the three to turn back. They travelled down the Rhine and by land to the Dutch port of Marsluys, arriving at Gravesend on 13 September 1814.[31]

The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she could not have foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to her genuine surprise, William Godwin refused to have anything to do with them.[32] Along with Claire, the couple moved into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square, where they maintained their intense programme of reading and writing and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as Thomas Jefferson Hogg and the writer Thomas Love Peacock.[33] Percy Shelley was sometimes forced to leave in order to dodge creditors.[34] On these occasions, the couple's distraught letters show their pain at separation.[35]

Pregnant and often ill, Mary Godwin had to cope with Percy's joy at the birth of his son by Harriet Shelley in late 1814 and with his constant outings with Claire Clairmont.[36] She was partly consoled by the visits of Hogg, whose companionship she warmed to, and who helped the couple financially.[37] Percy Shelley seems to have wanted Mary Shelley and Hogg to become lovers,[38] an idea that Mary did not dismiss, since in principle she believed in free love;[39] but she loved only Percy Shelley and seems to have gone no further than flirting with Hogg.[40] On 22 February 1815, she gave birth to a two-months premature baby girl, given little chance of survival.[41] On 6 March, she wrote to Hogg:

My dearest Hogg my baby is dead—will you come to see me as soon as you can. I wish to see you—It was perfectly well when I went to bed—I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be sleeping so quietly that I would not awake it. It was dead then, but we did not find that out till morning—from its appearance it evidently died of convulsions—Will you come—you are so calm a creature & Shelley is afraid of a fever from the milk—for I am no longer a mother now.[42]

The loss induced an acute depression in Mary Godwin, who was haunted by visions of her baby; but she fell pregnant again and had recovered by the summer.[43] After a revival in Percy Shelley's finances after the death of his grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley, the couple holidayed in Torquay and then rented a two-storey cottage at Bishopsgate, on the edge of Windsor Great Park.[44] Little is known about this period in Mary Godwin's life, since her journal from May 1815 to July 1816 is lost. At Bishopsgate, Percy Shelley wrote his poem Alastor; and Mary Godwin gave birth there to a second child, William (after Godwin), nicknamed "Willmouse", on 24 January 1816.

Lake Geneva and Frankenstein

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son travelled to Geneva with Claire Clairmont. They planned to spend the summer with the poet Lord Byron, whose recent affair with Claire had left her pregnant.[45] The party arrived at Geneva on 14 May 1816, where Mary called herself "Mrs Shelley", and Byron joined them on 25 May, with his young physician, John William Polidori (who originated modern vampire fiction).[46] Byron rented the Villa Diodati, close to Lake Geneva at the village of Cologny, and Percy Shelley a smaller building called Maison Chapuis, a vineyard away, on the waterfront.[47] They spent their time writing, boating on the lake, and talking into the wee hours.[48]

"It proved a wet, ungenial summer," Mary Shelley remembered in 1831, "and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house".[49] Amongst other subjects, the conversation turned to the experiments of 18th-century natural philosopher and poet Erasmus Darwin, who was said to have animated dead matter, and to galvanism and the feasibility of returning a corpse or assembled body parts to life.[50] Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company also amused themselves by reading German ghost stories,[51] prompting Byron to suggest they each write their own supernatural tale. Shortly afterwards, in a waking dream, Mary Godwin conceived the idea for Frankenstein:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world".[52]

She began writing what she assumed would be a short story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement,[53] she expanded this tale into her first novel, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, published in 1818.[54] She later described that summer in Switzerland as the moment "when I first stepped out from childhood into life".[55]

Bath and Marlow

On their return to England in September, Mary and Percy moved—with Claire Clairmont, who took lodgings nearby—to Bath, where they hoped to keep Claire’s pregnancy secret.[56] At Cologny, Mary Godwin had received two letters from her half-sister, Fanny Imlay, who alluded to her "unhappy life"; on 9 October, Fanny wrote an "alarming letter" from Bristol, which sent Percy Shelley racing off to search for her, without success. On the morning of 10 October, Fanny Imlay was found dead in a room at a Swansea inn, along with a suicide note and a laudanum bottle. On 10 December, the heavily pregnant body of Percy Shelley's wife, Harriet, was retrieved from the Serpentine, a lake in Hyde Park, London.[57] Both suicides were hushed up. Harriet’s family obstructed Percy Shelley's efforts—supported wholeheartedly by Mary Godwin—to assume custody of his two children by Harriet.[58] His lawyers advised him to improve his case by marrying; so he and Mary, who was pregnant again, married on 30 December 1816 at St Mildred's Church, Bread Street, London.[59] Mr and Mrs Godwin were present: the marriage ended the family rift.[60]

Claire Clairmont gave birth to a baby girl on 13 January, at first called Alba, later Allegra.[61] In March that year, the Chancery Court denied Percy Shelley custody of his children on the grounds of his moral unfitness and later placed them with a clergyman's family.[62] Also in March, the Shelleys moved with Claire and Alba to Albion House, a large, damp home at Marlow, Buckinghamshire, on the river Thames, where Mary Shelley gave birth to her third child, Clara, on 2 September. At Marlow, they entertained their new friends Marianne and Leigh Hunt, worked diligently on their writing, and often discussed politics.[63] Since returning from Switzerland, Mary Shelley had been working on Frankenstein, which she finished in early in the summer of 1817: it was published anonymously in January 1818. However, because it was published with a preface by Percy Shelley and was dedicated to William Godwin, reviewers and consumers assumed it was by Percy.[64] At Marlow, she edited the joint journal of their 1814 Continental journey, adding material written in Switzerland in 1816, and Percy Shelley's poem "Mont Blanc", into the History of a Six Weeks' Tour, published in November 1817. That autumn, Percy Shelley often lived away from home in London, to evade creditors. The threat of a debtor's prison, combined with their ill health and fears of losing custody of their children, contributed to the couple's decision to leave England for Italy on 12 March 1818, taking Claire Clairmont and Alba with them.[65] They had no intention of coming back.[66]

Italy

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in Venice. He had agreed to bring her up so long as Claire had nothing more to do with her.[67] The Shelleys then embarked on a roving existence, never settling in any one place for long.[68] Along the way, they accumulated a circle of friends and acquaintances who often moved with them. The couple devoted their time to writing, reading, learning, sightseeing, and socialising. The Italian adventure was, however, blighted for Mary Shelley by the deaths of both her children—Clara, in September 1818 in Venice, and William, in June 1819 in Rome.[69] These bereavements left her in a deep depression that isolated her from Percy Shelley,[70] who wrote in his notebook:

- My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone,

- And left me in this dreary world alone?

- Thy form is here indeed—a lovely one—

- But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road

- That leads to Sorrow’s most obscure abode.

- For thine own sake I cannot follow thee

- Do thou return for mine.[71]

For a time, Mary Shelley found solace only in her writing.[72] The birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, on 12 November 1819, finally lifted her spirits,[73] though she nursed the memory of her lost children till the end of her life.[74]

Italy provided the Shelleys, Byron, and other exiles with a political freedom unattainable at home. Despite its associations with personal loss, it became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise".[75] Their Italian years were a time of intense intellectual and creative activity for both Shelleys. While Percy composed a series of major poems, Mary wrote the autobiographical novel Matilda, the historical novel Valperga and the plays Proserpine and Midas. Mary wrote Valperga in order to help Godwin, who was still having financial difficulties. Percy refused to offer support, so she decided to do so herself.[76] She was often physically ill, however, and subject to depressions. She also had to cope with Percy Shelley’s interest in other women, such as Sophia Stacey, Emilia Viviani, and Jane Williams.[77] Since Mary Shelley shared his belief in the non-exclusivity of marriage, she formed emotional ties of her own among the men and women of their circle. She became particularly fond of the Greek revolutionary Prince Alexander Mavrocordato and of Jane and Edward Williams.[78]

In December 1818, the Shelleys travelled south with Claire Clairmont and their servants to Naples, where they stayed for three months, receiving no visitors.[80] In 1820, they found themselves plagued by accusations and threats from Paolo and Elise Foggi, former servants whom Percy Shelley had dismissed in Naples shortly after the Foggis had married.[81] The pair revealed that on 27 February 1819 in Naples, Percy Shelley had registered, as his child by Mary Shelley, a two-month-old baby girl named Elena Adelaide Shelley.[82] The Foggis also claimed, without proof, that the baby's mother was Claire Clairmont.[83] In order to explain this, historians and biographers have offered various possibilities: that Percy Shelley decided to adopt a local child; that the baby was his by Elise, Claire, or an unknown woman; or that she was Elise’s by Byron.[84] Mary Shelley insisted she would have known if Claire had been pregnant, but it is unclear how much she really knew.[85] The events in Naples, a city Mary Shelley later called a paradise inhabited by devils,[86] remain shrouded in mystery.[87] The only certainty is that she herself was not the child’s mother.[88] Elena Adelaide Shelley died in Naples on 9 June 1820.[89]

In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of typhus in a convent at Bagnacavallo.[90] Mary Shelley was distracted and unhappy in the cramped and remote Villa Magni, which she came to regard as a dungeon.[91] On 16 June, she miscarried and lost so much blood that her life was in danger. Rather than wait for a doctor, Percy Shelley sat her in a bath of ice to staunch the bleeding, an act the doctor later told him saved her life.[92] All was not well between the couple that summer, however, and Percy Shelley gave more attention to Jane Williams and other women than to his debilitated and depressed wife.[93] In his poetry, Mary Shelley is described in cold terms and no longer as his muse.[94]

The coast offered Percy Shelley and Edward Williams the chance to enjoy their "perfect plaything for the summer", a new sailing boat.[95] The boat had been designed by Daniel Roberts and Edward Trelawny, a fan of Byron's who had joined the party in January 1822.[96] On 1 July 1822, Percy Shelley, Edward Williams, and Captain Daniel Roberts sailed south down the coast to Livorno. There Percy Shelley discussed the launch of a radical magazine called The Liberal with Byron and Leigh Hunt.[97] On 8 July, he and Edward Williams set out on the return journey to Lerici with their eighteen-year-old boatboy, Charles Vivian.[98] They never reached their destination. A letter arrived at Villa Magni from Hunt to Percy Shelley, dated 8 July, saying, "pray write to tell us how you got home, for they say you had bad weather after you sailed monday & we are anxious".[99] "The paper fell from me," Mary told a friend later. "I trembled all over".[100] She and Jane Williams rushed desperately to Livorno and then to Pisa, in the fading hope that their men were still alive. Ten days after the storm, three bodies washed up on the coast near Viareggio, mid-way between Livorno and Lerici. Trelawny, Byron, and Hunt cremated Percy Shelley’s corpse on the beach at Viareggio.[101]

Return to England and writing career

| [Frankenstein] is the most wonderful work to have been written at twenty years of age that I ever heard of. You are now five and twenty. And, most fortunately, you have pursued a course of reading, and cultivated your mind in a manner the most admirably adapted to make you a great and successful author. If you cannot be independent, who should be? |

| — William Godwin to Mary Shelley[102] |

After her husband's death, Mary Shelley lived for a year with Leigh Hunt and his family in Genoa, where she often saw Byron and transcribed his poems. She decided to live by her pen and for her son, but her financial situation was precarious. On 23 July 1823, she left Genoa for England and stayed with her father and stepmother in the Strand until a small advance from her father-in-law enabled her to lodge nearby.[103] Sir Timothy Shelley had at first agreed to support his grandson, Percy Florence, only if he were handed over to an appointed guardian. Mary Shelley rejected this plan instantly.[104] She managed instead to wring out of Sir Timothy a limited and repayable allowance, but to the end of his days he refused to meet her in person and conducted his dealings with her through lawyers. Mary Shelley busied herself with editing her husband's poems, among other literary endeavors, but concern for her son restricted her freedom. Sir Timothy Shelley threatened to stop Percy Florence's allowance should any biography of Percy Bysshe Shelley be published.[105] In 1826, after the death of Charles Shelley (Percy Shelley's son by a previous marriage), Percy Florence became the legal heir of the Shelley estate. Sir Timothy raised Mary Shelley's allowance from £100 a year to £250, but their frosty relationship did not change.[106] Mary Shelley enjoyed the stimulating society of William Godwin's circle, but poverty prevented her from socialising as widely as she wished. She also felt ostracized by those who, like Sir Timothy, disapproved of her elopement and relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley.[107]

In summer 1824, Mary Shelley moved to Kentish Town in north London to be near Jane Williams. She may have been, in the words of her biographer Muriel Spark, "a little in love" with Jane, who later disillusioned her by spreading hurtful gossip about her adequacy as a wife to Percy Shelley.[108] At around this time, Mary Shelley was working on her novel, The Last Man (1826); she also spent time assisting a series of friends who were writing memoirs of Byron and Shelley, the beginning of her attempts to immortalize Shelley.[109] She also met the American actor John Howard Payne and the American writer Washington Irving. Payne fell in love with her, and in summer 1826 asked her to marry him. She refused, saying that after being married to one genius, she could only marry another. Payne therefore tried without success to talk his friend Irving into proposing in his place. Mary Shelley was aware of Payne's endeavours, but how seriously she took them is not clear.[110]

In 1827, Mary Shelley was party to a scheme whereby her friend Isabel Robinson and Isabel's lover, Maria Mary Dods, who wrote under the name David Lyndsay, were enabled to adopt a life together in France as man and wife.[112] With the help of Payne, whom she kept in the dark about the details, Mary Shelley obtained false passports for the couple, at considerable risk to her own reputation.[113] While visiting the couple in Paris, she fell ill with smallpox.[114]

During the period 1827–40, Mary Shelley was busy as an editor and writer. She wrote the novels, Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), and Falkner (1837). She contributed five volumes of Lives on Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French authors, to Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopædia. She also wrote stories for lady's magazines. Needing money, Mary Shelley wrote to support herself and her father; both looked out for publishers for the other.[115] In 1830, she sold the copyright for a new edition of Frankenstein for £60 to Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley for their new Standard Novels series.[116] After Godwin's death in 1836, at the age of eighty, she worked dutifully on assembling his letters and a memoir for publication, as he had requested in his will—she was to be responsible for his posthumous reputation. After two years of work, however, she abandoned the project.[117] Throughout this period, she also championed Percy Shelley's poetry, promoting its publication and quoting it in her works. By 1837, Percy's works had become well-known and increasingly admired.[118] In the summer of 1838 Edward Moxon, the publisher of Tennyson and the son-in-law of Charles Lamb, proposed publishing a collected works of Percy Shelley. Mary was paid £500 to edit the Poetical Works (1838), which Sir Timothy still demanded not include a biography.[119]

Mary Shelley continued to treat potential romantic partners with caution. In 1828, she met and flirted with the French writer Prosper Mérimée, and her one surviving letter to him appears to be a deflection of his declaration of love.[120] She was delighted when her old friend from Italy, Edward Trelawny, returned to England; in subsequent letters, he too talked of marriage, but she ruled it out.[121] Their friendship had altered, however, when she refused to cooperate with his proposed biography of Percy Shelley; and he later reacted angrily when she omitted the atheistic section of Queen Mab from Percy Shelley's poems.[122] Oblique references in her journals, from the early 1830s until the early 1840s, suggest that Mary Shelley had feelings for the radical politician Aubrey Beauclerk, who may have disappointed her by twice marrying others.[123]

Mary Shelley's first concern during these years was the welfare of her son, Percy Florence. She honoured her late husband's wish that his son attend public school, and, with Sir Timothy's grudging help, had him educated at Harrow. To avoid boarding fees, she moved to Harrow on the Hill herself so that Percy could attend as a day scholar.[124] Though Percy went on to Trinity College, Cambridge and dabbled in politics and the law, he showed no sign of his parents' gifts.[125] However, he was devoted to his mother, and after he left the university in 1841, he came to live with her.

Final years and death

In 1840 and 1842, mother and son travelled together on the continent, journeys that Mary Shelley recorded in Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 (1844).[126] In 1844, Sir Timothy Shelley finally died at the age of ninety, "falling from the stalk like an overblown flower", as Mary put it.[127] For the first time, she and her son were financially independent, though the estate proved less valuable than they had hoped.[128]

In the mid 1840s, Mary Shelley was the target of a series of blackmailers. In Paris, she met a dashing Italian political exile and writer named Ferdinand Gatteschi, to whom she gave money and wrote unguarded letters. In 1845, Gatteschi used these letters in an attempt to blackmail her. Mary Shelley wrote to Claire Clairmont, "I am indeed humbled—& feel all my vanity & folly & pride—my credulity I can forgive but not my total want of common sense".[129] Her son's friend, lawyer Alexander Knox, came to the rescue. He set off for Paris, where he bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters in question.[130] Two weeks later, a forger calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late Lord Byron, contacted Mary Shelley offering to sell her letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary Shelley negotiated the purchase of some of them through her late husband's friend Thomas Hookham. Two years later, G. Byron resurfaced with more demands, threatening to release copies of the letters he had handed over. After further exchanges with Hookham, however, nothing more was heard from him.[131] In 1845, Percy Bysshe Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin, once part of the Shelley circle in Italy, approached Mary Shelley claiming to have written a damaging biography of Percy Shelley that he was willing to suppress in return for £250, which he said was the price offered by a publisher.[132] The threat caused Mary Shelley much anxiety, but she refused to give in to Medwin. "An attempt to extort money finds me quite hardened, " she told Hunt. "I have suffered too much from things of this kind."[133]

In 1848, Percy Florence married Jane Gibson St John, and the marriage was a happy one. Mary Shelley and Jane were fond of each other,[135] and Mary lived with her son and daughter-in-law at Field Place, Sussex, the Shelleys' ancestral home, and at Chester Square, London, and accompanied them on travels abroad.

Mary Shelley's last years were, however, blighted by illness. From 1839, she suffered from headaches and bouts of paralysis in parts of her body, which sometimes prevented her from reading and writing.[136] On 1 February 1851, at Chester Square, she died of a suspected brain tumour at the age of fifty-three. According to Jane Shelley, Mary Shelley had asked to be buried with her mother and father; but Percy and Jane, considering the graveyard at St Pancras to be "dreadful", chose to bury her instead at St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, near their new home at Boscombe.[137] On the first anniversary of Mary Shelley's death, the Shelleys opened her box-desk. Inside they found locks of her dead children's hair, a notebook she had shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem Adonaïs with one page folded round a silk parcel containing some of his ashes and the remains of his heart.[138]

Literary life

By the time she met Percy Shelley in 1814, Mary Godwin was already primed for a literary life. Her father had encouraged her to learn to write by writing letters.,[139] and her favourite occupation as a child was writing stories.[140] Her first published work is often thought to have been Mounseer Nongtongpaw,[141] comic verses written for Godwin's publishing company when she was ten and a half, though the attribution has been questioned.[142] Visitor Aaron Burr noted in his journal an occasion on which Mary Shelley wrote a speech for her eight-year-old brother William to deliver in the family schoolroom.[143] Percy Shelley vigorously encouraged Mary Shelley's writing. She wrote later: "My husband was, from the first, very anxious that I should prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enrol myself on the page of fame. He was forever inciting me to obtain literary reputation".[144]

When they eloped to France in summer 1814, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley began a joint journal,[145] which they published in 1817 under the title History of a Six Weeks' Tour, adding four letters, two by each of them, based on their visit to Geneva in 1816, and Percy Shelley's poem "Mont Blanc". The work celebrates youthful love and political idealism and consciously follows the example of Mary Wollstonecraft and others who had combined travelling with writing.[146] The perspective of the History is philosophical and reformist rather than that of a conventional travelogue; in particular, it addresses the effects of politics and war on France.[147] The letters the couple wrote on the second journey confront the "great and extraordinary events" of the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo after his "Hundred Days" return in 1815. They explore the sublimity of Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc as well as the revolutionary legacy of the philosopher and novelist Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[148]

Fiction

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley's first and most famous novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, was published on 1 January 1818, in a run of 500 copies.[149] Frankenstein's central story is narrated to the Arctic explorer Captain Walton by Victor Frankenstein, who is pursuing a nameless creature he has manufactured from the "lifeless matter" of corpses across the frozen seas. Frankenstein relates how, after his creature came to life, he fled in disgust, allowing it to escape. After the creature kills Frankenstein's brother, Frankenstein confronts him in the Alps, where the creature narrates his experiences and explains how he turned from a natural life of goodness to a life of evil. In return for the creature's promise to leave Europe, Frankenstein agrees to make him a female companion; but he later destroys his unfinished work in fit of disgust. The creature, who now stalks Frankenstein's every move, murders Frankenstein's best friend, Clerval, and then his bride, Elizabeth. Bent on destroying the creature, Frankenstein pursues him to the Arctic, and is picked up, frozen and exhausted, by Captain Walton. After narrating his story, he dies. The creature appears and wails with grief over Frankenstein's coffin. Vowing to kill himself in turn, he builds his own funeral pyre.

Frankenstein, like many works of its period, mixes a visceral and alienating subject matter with speculative and thought-provoking themes.[150] Mary Shelley adopts elements of the Gothic genre of mystery and horror. Rather than focusing on the twists and turns of the plot, however, she foregrounds the mental and moral struggles of the protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, and imbues the text with her own brand of politicised Romanticism. The novel has always provoked multiple, often conflicting, interpretations. In the view of critic and editor Betty T. Bennett, however, these interpretations commonly acknowledge Mary Shelley's "consistent, larger metaphoric question of the exercise of power and responsibility, personal and societal".[151] Some critics have seen the novel as a warning against scientific interference with nature, or against man's pretension to godlike power. Mary Shelley believed, like her parents and her husband, in the Enlightenment idea that man could improve society through the responsible exercise of political power, but that irresponsible use of power led to chaos.[152] Unlike Prometheus, Victor Frankenstein creates his creature not on behalf of humanity but for his own selfish reasons, without thought of the social consequences.[153]

Many modern critics have read Frankenstein from a psychological standpoint. For example, feminist literary critics Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in their seminal book The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) argue that Shelley defined her writing persona largely through literature, and particularly through the works of her parents.[154] They contend that in Frankenstein in particular, Shelley was responding to the masculine literary tradition represented by John Milton's Paradise Lost. In their interpretation, Shelley reaffirms this masculine tradition, including the misogyny inherent in it, while at the same time her work "conceal[s] fantasies of equality that occasionally erupt in monstrous images in rage".[155] Reading the first edition of Frankenstein as part of a larger pattern in Shelley's writing, which begins with literary self-assertion and ends with conventional femininity, Mary Poovey argues that these same "competing impulses" are already present in Shelley's earliest novel.[156] Poovey sees in Frankenstein's multiple narratives an opportunity for Shelley to split her artistic persona, she can "express and efface herself at the same time".[157] Shelley's own fears of self-assertion are reflected in the character of Frankenstein, who is punished for his egotism by losing all of his domestic ties.[158]

The anonymous first edition of Frankenstein received reviews that ranged from hostility to appreciation, alerted by the dedication to William Godwin and by Percy Shelley's preface. The majority of the reviews based their assessment on whether or not the public would benefit from reading the novel; reviewers who felt that the tale might offer significant moral lessons to the reader tended to approve of the novel while those who felt that it might corrupt them tended to disapprove of it.[159] The novel won approval among Mary Shelley's literary circle, and was republished under her own name in 1823, edited by her father. In 1831, when the novel was published in a third edition for Colburn and Bentley's Standard Novels Series, Shelley herself made substantial revisions to the text.[160] Frankenstein has now entered the public imagination, popularised at first by Richard Brinsley Peake's adaptation for the stage in 1823.[161] The subsequent fame of Frankenstein has spawned its own mythology: the creature is regularly invoked, often inaccurately, in diverse non-literary contexts.[162]

Although the novel has been popular since its publication, it was not until the birth of feminist literary criticism and the beginnings of cultural studies in the 1970s that it was taken seriously as a literary work. The first book to be published on it, The Endurance of "Frankenstein", which attempted to explain why the novel was popular, was published in 1979.[163] It is this tension between "great literary work" and "popular literary work" that has often shaped the scholarship on Frankenstein. Attempting to establish significant lineages in the academy, scholars of women's writing and science fiction have both claimed that Frankenstein is a great work of literature.[164] On the other hand, while attempting to break down the Western canon, other scholars have argued that the meaning of "great works of literature" is impossible to define and have used Frankenstein as a text to do so. Marxist and cultural studies critics have argued that the novel should be studied precisely because of its fame and that all of film, comic book, and other adaptive works are an important part of the culture's heritage. They criticize the distinction between "high" and "low" culture that has arisen and tend to discount what they view as arbitrary differences.[165]

Matilda, Valperga, and The Last Man

Between August 1819 and February 1820, Mary Shelley wrote her short novel Matilda,[166] on the well-trodden Romantic themes of incest and suicide.[167] Narrating from her deathbed, the romantic heroine Matilda recounts her unnamed father's confession of his incestuous love for her, followed by his suicide by drowning. Matilda’s relationship with a gifted young poet called Woodville fails to reverse her emotional withdrawal or prevent her lonely death. Commentators often read the text as autobiographical, the three central characters standing for William Godwin, Mary Shelley, and Percy Shelley.[168] Critic Pamela Clemit, however, resists a purely autobiographical reading, contesting that Matilda is an artfully crafted novel in the style of William Godwin, deploying confessional and unreliable narrations and Godwin's device of the pursuit.[169] The novel's first editor, Elizabeth Nitchie, noted its faults of "verbosity, loose plotting, somewhat stereotyped and extravagant characterization" but praised a "feeling for character and situation and phrasing that is often vigorous and precise".[170]

Mary Shelley sent the finished novel to her father in England, to submit for publication. However, though Godwin admired aspects of the tale, he found the incest theme "disgusting and detestable" and failed to return the manuscript despite his daughter's repeated requests.[171] Matilda was finally published in 1959, edited by Elizabeth Nitchie from dispersed papers.[172] It has become perhaps Mary Shelley's best-known work after Frankenstein.[2]

Godwin was of more assistance with Mary Shelley's next novel, Valperga; or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca, which she sent him in late 1821; he edited and shortened it and arranged for its publication in February 1823.[173] This historical novel relates the adventures of the early-fourteenth-century despot Castruccio Castracani, a real historical figure who became the lord of Lucca and conquered Florence. In the novel, his armies threaten the fictional fortress of Valperga, governed by Countess Euthanasia, the woman he loves. He forces her to choose between her feelings for him and political liberty. She chooses the latter and sails off to her death.

Valperga earned largely positive reviews, but it was judged as a love story, its ideological framework overlooked.[174] Through the perspective of medieval history, Mary Shelley addresses a live issue in post-Napoleonic Europe, the right of autonomously governed communities to political liberty in the face of imperialistic encroachment.[175] She opposes Castruccio's compulsive greed for conquest with a female alternative, Euthanasia's government of Valperga on the principles of reason and sensibility.[176] In the view of Valperga's recent editor Stuart Curran, the work represents a "feminist recasting of Scott's masculinist historical novel".[177] Modern critics draw attention to Mary Shelley's republicanism, and her interest in questions of political power and moral principles.[178] Valperga has also been praised for its sophisticated narrative form and its authenticity of detail.[179] It was not, however, republished in Mary Shelley's lifetime, and she later remarked that it never had "fair play".[180]

After Valperga, Mary Shelley wrote two dramas, Proserpine and Midas, possibly for a young audience, and a short story, Maurice, for the eleven-year-old daughter of a friend.[181] The death of Percy Shelley in 1822 made it necessary for her to adopt a more professional approach as a writer. From this time, she took jobbing work as an editor and regularly wrote essays, travel pieces, and reviews for publication. She also often contributed short stories for gift books or annuals, including sixteen for The Keepsake, which was aimed at middle-class women and bound in silk, with gilt-edged pages. In this field, Mary Shelley has been described as a "hack writer", and "wordy and pedestrian". Critic Charlotte Sussman, however, points out that other leading writers of the day took advantage of this profitable market.[182] Mary Shelley always saw herself, above all, as a novelist. She wrote to Hunt, "I write bad articles which help to make me miserable—but I am going to plunge into a novel and hope that its clear water will wash off the mud of the magazines".[183]

The novel Mary Shelley had in mind, with a "vivid conception of the story", was The Last Man, which was published in 1826.[184] Set in a republican Britain in the twenty-first century, the novel is a futuristic fable of the end of human civilisation. It follows the political and emotional adventures of a small group of characters, a "happy circle", who are killed off one by one as a lethal plague sweeps across Europe, until only one man remains, wandering a deserted Rome. Mary Shelley modelled the central characters on her Italian circle: Lord Raymond, for example, who leaves England to fight for the Greeks and dies in Constantinople, is based on Lord Byron; and the utopian Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who leads his followers in search of a natural paradise and dies when his boat sinks in a storm, is a fictional portrait of Percy Shelley.[185] The novel not only expresses Mary Shelley's pain at the loss of her community of the "Elect",[186] as she called them,[187] but it questions the Romantic political ideals they stood for.[188] In a sense, the plague is metaphorical, since the revolutionary idyll of the élite group is corroded from within by flaws of human nature.[189]

The Last Man received the worst reviews of all Mary Shelley's novels: most reviewers derided the very theme of lastness, which had become a common one in the previous two decades. Individual reviewers labelled the book "sickening", criticised its "stupid cruelties", and called the author's imagination "diseased".[190] The reaction startled Mary Shelley, who promised her publisher a more popular book next time. Nonetheless, she later spoke of The Last Man as one of her favourite works. The novel was not republished in England until the twentieth century, when it received new critical attention, perhaps because the notion of lastness had become more relevant.[191] Today many critics regard The Last Man as Mary Shelley's second-best novel.[192]

Perkin Warbeck, Lodore, and Falkner

In her next novel, The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck, published in 1830, Mary Shelley returned to The Last Man's message that an idealistic political system is impossible without an improvement in human nature.[193] This historical novel, influenced by those of Sir Walter Scott,[194] fictionalises the exploits of Perkin Warbeck, a pretender to the throne of King Henry VII who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the second son of King Edward IV. Mary Shelley believed that Warbeck really was Richard and had escaped from the Tower of London.[195] She endows his character with elements of Percy Shelley, portraying him sympathetically as "an angelic essence, incapable of wound", who is led by his sensibility onto the political stage.[196] She seems to have identified herself with Richard's wife, Lady Katherine Gordon, who survives after her husband's death by making accommodation with his political enemies.[197] Lady Gordon stands for the values of friendship, domesticity and equality; through her, Mary Shelley offers a female alternative to the masculine power politics that destroy Richard.[198] Perkin Warbeck was generally well received; the Edinburgh Literary Journal's critic, for example, said it bore "the stamp of a powerful mind".[199] The novel is not, however, regarded as one of Mary Shelley's most important. The character of Lady Gordon has been called "pathetic in her hand-wringing ineffectuality".[200] The political contradictions of the novel have also been noted,[201] as well as its uneasy mix of the influences of Scott and the Jacobean playwright John Ford.[202]

Mary Shelley's last two novels, Lodore and Falkner have contemporary settings. In Lodore, published in 1835,[203] Shelley focused her theme of power and responsibility on the microcosm of the family.[204] The central story follows the fortunes of the wife and daughter of the title character, Lord Lodore, who is killed in a duel at the end of the first volume, leaving a trail of legal, financial, and familial obstacles for the two "heroines" to negotiate. Mary Shelley places female characters at the centre of the ensuing narratives: Lodore's daughter, Ethel, raised to be over-dependent on paternal control; his estranged wife, Cornelia, preoccupied with the norms and appearances of aristocratic society; and the intellectual and independent Fanny Derham, with whom both are contrasted.[205]

Lodore was a success with the reviewers: Fraser's Magazine praised its "depth and sweep of thought", for example; and it prompted The Literary Gazette to call Mary Shelley "one of the most original of our modern writers".[206] Later nineteenth-century critics were more dubious: in 1886, Edward Dowden called Lodore "biography transmuted for the purposes of fiction"; in 1889, Florence Marshall remarked that Lodore was "written in a style that is now out of date".[207] The case for the novel has been made recently by, among others, its editor Lisa Vargo, who notes its engagement with political and ideological issues, particularly the education and social role of women.[208] She suggests that Lodore dissects a patriarchal culture that separated the sexes and pressured women into dependence on men.[209] In the view of critic Betty T. Bennett, "the novel proposes egalitarian educational paradigms for women and men, which would bring social justice as well as the spiritual and intellectual means by which to meet the challenges life invariably brings".[210]

In her last novel, Falkner, published in 1837, Mary Shelley again charted a young woman's education under a tyrannical father figure.[211] As a six-year-old orphan, Elizabeth Raby prevents Rupert Falkner from committing suicide; Falkner then adopts her and brings her up to be a model of virtue. However, she falls in love with Gerald Neville, whose mother Falkner had unintentionally driven to her death years before. When Falkner is finally acquitted of murdering Neville's mother, Elizabeth's female values subdue the destructive impulses of the two men she loves, who are reconciled and unite with Elizabeth in domestic harmony. Falkner is the only one of Mary Shelley's novels in which the heroine's agenda triumphs.[212] In critic Kate Ferguson Ellis's view, the novel’s resolution proposes that when female values triumph over violent and destructive masculinity, men will be freed to express the "compassion, sympathy, and generosity" of their better natures.[213]

Critics have until recently cited Lodore and Falkner as evidence of a conservative retrenchment by their author. In 1984, Mary Poovey identified the retreat of Mary Shelley’s reformist politics into the "separate sphere" of the domestic.[214] As with Lodore, contemporary critics reviewed the novel as a romance, overlooking its political subtext and noting its moral issues as purely familial. Bennett argues, however, that Falkner is as concerned with power and political responsibility as Mary Shelley's previous novels.[215] Poovey suggested that Mary Shelley wrote Falkner to resolve her conflicted response to her father's combination of libertarian radicalism and stern insistence on social decorum.[216] Critics view Falkner neither as notably feminist,[217] nor as one of Mary Shelley's strongest novels, though she herself believed it could be her best. The novel has been criticised for its two-dimensional characterisation.[218] In Bennett's view, "Lodore and Falkner represent fusions of the psychological social novel with the educational novel, resulting not in romances but instead in narratives of destabilization: the heroic protagonists are educated women who strive to create a world of justice and universal love".[219]

Non-fiction

Mary Shelley's last full-length book was Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843, written in the form of letters and published in 1843, which recorded her travels with her son Percy Florence and his university friends. In the tradition of Mary Wollstonecraft's Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and her own A History of a Six Weeks' Tour, Shelley maps her personal and political landscape in Rambles.[220] Between observations on scenery, culture, and "the people, especially in a political point of view",[221] she uses the travelogue form to explore her roles as a widow and mother and to reflect on revolutionary nationalism in Italy.[222] She also records her "pilgrimage" to scenes associated with Percy Shelley".[223] According to critic Clarissa Orr, Mary Shelley's adoption of a persona of philosophical motherhood gives Rambles the unity of a prose poem, with "death and memory as central themes".[224] At the same time, Shelley makes an egalitarian case against monarchy, class distinctions, slavery, and war.[225]

Between 1832 and 1839, Mary Shelley also wrote many biographical essays for five volumes of Dionysius Lardner's Lives, part of his Cabinet Cyclopaedia.[226] Until the republication of these essays in 2002, their significance was not appreciated.[227] They reveal not only that Mary Shelley produced far more of these lives of famous Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and French writers and scientists than previously thought, but also a radicalism and an alertness to historical gender issues which belie the once-accepted notion that she became politically conservative as she grew older.[228]

Editorial work

Soon after Percy Shelley’s death, Mary Shelley determined to write his biography. In a letter of 17 November 1822, she announced: "I shall write his life—& thus occupy myself in the only manner from which I can derive consolation".[230] However, her father-in-law, Sir Timothy Shelley, had effectively banned her from doing so.[231] Beginning in 1824, with the publication of Percy Shelley's Posthumous Poems, Mary Shelley dedicated herself to building up his poetic reputation. In 1839, while she was working on the Lives, she prepared a new edition of his poetry: the edition was, as literary critic Susan Wolfson puts it, "the canonizing event" in the history of her husband's reputation.[232] The following year, she edited a volume of essays, letters, translations, and fragments, and throughout the 1830s, she introduced a wider audience to his poetry by publishing assorted works in the Keepsake, a gift-book annual.[233]

Evading Sir Timothy's ban on a biography of his son, Mary Shelley included her own annotations and personal reflections on her husband's life and work in many of these edited works, most notably the Poetical Works.[234] To make his works more acceptable to a Victorian audience, she chose to represent Percy Shelley as a lyrical poet rather than a political writer. Therefore, she downplayed his radical political views and emphasized "his unworldliness, his philanthrophy, [and] his delicate health".[235] She explained his political radicalism through sentimentalism, arguing that his republicanism was simply sympathy for those who were suffering.[236] She recounted romantic stories of his benevolence, domesticity, and his love of the natural world.[237] Mary Shelley also described herself as "practical muse to the living poet", describing in her notes how she had suggested revisions as Percy was writing.[238]

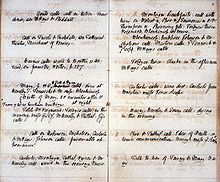

Despite the emotional stress of this undertaking,[239] Mary Shelley proved herself a professional and scholarly editor.[240] Working from Percy's messy notebooks, she attempted to decipher his handwriting and to decide on a chronology for his writings.[241] However, she was forced into several compromises. In principle, she believed in publishing every last word of her husband's work,[242] but she found herself obliged to omit certain passages, either by pressure from her publisher, Edward Moxon, or in deference to public propriety.[243] For example, she had removed the atheistical sections from Queen Mab for the first edition; after she restored them in the second edition, Moxon was prosecuted and found guilty of blasphemous libel. He was not punished, however.[244] Her omissions led to criticism, often stinging, from members of Percy Shelley's former circle, particularly from Edward Trelawny, and from Thomas Jefferson Hogg, who wrote her an "insulting letter" berating her for omitting the Percy Shelley's dedication of Queen Mab to his first wife, Harriet (this was restored in the second edition).[245] Reviewers accused Mary Shelley, among other things, of the "emasculation" of Queen Mab and of indiscriminate inclusions.[246] Despite their troubled reception, her notes have remained an essential source for the study of Percy Shelley's work, with which they have often been reprinted.[247]

Reputation

Mary Shelley was taken seriously as a writer in her own lifetime, though reviewers often missed the political edge to her novels. After her death, however, she was chiefly remembered only as the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley and as the author of Frankenstein. The well-meaning attempts of her son and daughter-in-law to "Victorianise" her memory through the censoring of letters and biographical material contributed to a perception of Mary Shelley as a more conventional, less reformist figure than her works suggest. Her own timid omissions from Percy Shelley's works and her quiet avoidance of public controversy in the later years of her life added to this impression. Commentary by Hogg, Trelawny, and other admirers of Percy Shelley also tended to downplay Mary Shelley's radicalism. Trelawny's Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author (1878) praised Percy Shelley at the expense of Mary, questioning her intelligence and even her authorship of Frankenstein.[248] Lady Shelley, Percy Florence's wife, responded in part by editing the collection of letters she had inherited, published privately as Shelley and Mary in 1882. Aiming to present Mary and Percy Shelley in the best light, she attempted to misrepresent Claire Clairmont's age at the time of the trio's trip to Europe and other details. She also solicited biographies of the couple from the scholar Edward Dowden, offering him limited access to the family's archive.[249]

The eclipse of Mary Shelley's reputation as a novelist meant that, until the last thirty years, most of her works remained out of print, obstructing a larger view of her achievement. In recent decades, the republication of almost all her writings has stimulated a new recognition of its value. Scholars now consider Mary Shelley to be a major Romantic figure, significant for her literary achievement and her political voice as a woman and a liberal.[250]

List of works

- Mounseer Nongtongpaw; or, The Discoveries of John Bull in a Trip to Paris, Juvenile Library, 1808

- History of Six Weeks' Tour through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland, with Letters Descriptive of a Sail round the Lake of Geneva, and of the Glaciers of Chamouni, with contributions by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Hookham, 1817

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (novel), three volumes, Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones, 1818, revised edition, one volume, Colburn & Bentley, 1831, two volumes, Carey, Lea, & Blanchard, 1833

- Mathilda (1819 novel), edited by Elizabeth Nitchie, University of North Carolina Press, 1959

- Valperga; or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (novel), three volumes, Whittaker, 1823.

- Editor of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Hunt, 1824

- The Last Man (novel), three volumes, Colburn, 1826, two volumes, Carey, Lea, & Blanchard, 1833

- The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (novel), three volumes, Colburn & Bentley, 1830, two volumes, Carey, Lea, & Blanchard, 1834

- Lodore (novel), three volumes, Bentley, 1835, one volume, Wallis & Newell, 1835

- Falkner (novel) three volumes, Saunders & Otley, 1837, one volume, Harper & Brothers, 1837

- Editor of P. B. Shelley, The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, four volumes, Moxon, 1839

- Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842, and 1843, two volumes, Moxon, 1844

- The Choice: A Poem on Shelley's Death, edited by H. Buxton Forman, [London], 1876

- The Mortal Immortal (short story), Mossant, Vallon, 1910

- Proserpine and Midas: Two Unpublished Mythological Dramas, edited by A. Koszul, Milford, 1922

- Contributor to Volumes 86-88 and 102-103 in The Cabinet of Biography, Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopedia, 1835-1839

- Contributor of stories, reviews, and essays for London Magazine, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Examiner, and Westminster Review

- Contributor of stories to an annual gift book, The Keepsake, 1828-1838

- Collections of Mary Shelley's works are housed in Lord Abinger's Shelley Collection on deposit at the Bodleian Library, the New York Public Library, the Huntington Library, the British Library, and in the John Murray Collection

- Excluding many collections, such as Mary and Shelley's journals and letters

- The Bride of Modern Italy (?)

- The Dream (?)

- Ferdinando Eboli (?)

- The Invisible Girl (?)

- Roger Dodsworth:The Reanimated Englishman (1826)

- The Sisters of Albano (?)

- The Transformation (?)

See also

Notes

- ^ Seymour, 458.

- ^ a b Clemit, "From The Fields of Fancy to Matilda ", 64.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 120–21.

- ^ Seymour, 28–29; St Clair, 176-78.

- ^ St Clair, 179-188; Seymour, 31-34.

- ^ Seymour, 38, 49.

- ^ St Clair, 199–207.

- ^ Claire's first name was "Jane", but from 1814 (see Gittings and Manton, 22) she preferred to be called "Claire" (her second name was "Clara"), which is how she is known to history. To avoid confusion, this article calls her "Claire" throughout.

- ^ Seymour, 47–49; St Clair, 238-54. St Clair notes that "it is easy to forget in reading of these crises [in the lives of the Godwins and the Shelleys] how unrepresentative the references in surviving documents may be. It is easy for the biographer to give undue weight to the opinions of the people who happen to have written things down." (246)

- ^ St Clair, 243–44, 334; Seymour, 48.

- ^ Letter to Percy Shelley, 28 October 1814. Selected Letters, 3; St Clair, 295; Seymour 61.

- ^ St Clair, 295.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 16–17.

- ^ Sunstein, 38–40; Seymour, 53.

- ^ Sunstein, 58; Spark, 15.

- ^ Seymour, 74–75. Dundee was a stronghold of radical and Jacobin dissent, and the Baxter family were Glassite Calvinists.

- ^ Quoted in Hindle, Introduction to Frankenstein, xvii.

- ^ Seymour, 71-74.

- ^ Spark, 17–18; Seymour, 73-86.

- ^ Qtd. in Spark, 17.

- ^ St Clair, 358.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 17; St Clair, 357; Seymour, 89. There is no direct evidence that Mary Godwin met Percy Shelley at this time; Bennett believes that she "most likely" did, because he sometimes dined with the Godwins.

- ^ Sunstein, 70–75; Seymour, 88.

- ^ Spark, 19–22; St Clair, 358.

- ^ Seymour, 94, 100; Spark, 22–23. Some critics have seen hypocrisy in Godwin's opposition, in view of his liberal politics; biographer Muriel Spark points out, however, that he may simply have felt that "a married man whose wife had often been the Godwins' guest" was an unsuitable partner for his daughter.

- ^ Letter to Maria Gisborne, 30 October–17 November, 1824. Seymour, 49.

- ^ St Clair, 373; Seymour, 89 n, 94–96; Spark, 23 n2.

- ^ Spark, 24; Seymour, 98-99.

- ^ Quoted in Sunstein, 84.

- ^ Spark, 26–30.

- ^ Spark, 30; Seymour, 109, 113.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 20; St Clair, 373; Sunstein, 88–89; Seymour, 115-16.

- ^ Spark, 31–32.

- ^ Spark, 36–37; St Clair, 374.

- ^ Sunstein, 91–92; Seymour, 122–23.

- ^ "Journal 6th December—Very Unwell. Shelley & Clary walk out, as usual, to heaps of places . . . A letter from Hookham to say that Harriet has been brought to bed of a son and heir. Shelley writes a number of circular letters on this event, which ought to be ushered in with ringing of bells, etc., for it is the son of his wife." Quoted in Spark, 39.

- ^ Spark, 38–44.

- ^ St Clair, 375.

- ^ Sunstein, 94–97; Seymour, 127

- ^ Spark, 41–46; Seymour, 126–27; Sunstein, 98–99. Sunstein speculates, however, that the two made love in April 1815.

- ^ Seymour, 128.

- ^ Quoted in Spark, 45.

- ^ St Clair, 375; Spark, 45, 48.

- ^ Sunstein, 93–94, 101; Seymour, 127–8, 130. Sir Bysshe died on 5 January 1815. Percy Shelley did not reap the benefit until the end of a Chancery suit in April.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 28–31.

- ^ Sunstein, 117.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 31; Seymour, 152. Sometimes spelled “Chappuis”; Wolfson, Introduction to Frankenstein, 273.

- ^ Sunstein, 118.

- ^ Preface to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein; Sunstein, 118. It is now known that the violent storms were a repercussion of the volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, the year before. See also The Year Without a Summer.

- ^ Holmes, 328; see also Mary Shelley’s introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

- ^ In a French translation, called Fantasmagoriana, ou Receuil d’histoires d’apparitions de spectres, revenants, fantômes, etc. . Of the night of 18 June, Polidori wrote in his journal: “Twelve o’clock really began to talk ghostly”. Holmes, 328.

- ^ Quoted in Spark, 157, from Mary Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein. There is speculation that this was based on work by Andrew Crosse of Fyne Court, Broomfield, Somerset who carried out early experiments passing an electrical current through a chemical solution in an attempt to induce crystal formation. On the 26th day of the experiment he saw what he described as "the perfect insect, standing erect on a few bristles which formed its tail" probably from contaminated instruments. Seymour, 157, argues that evidence from Polidori's diary conflicts with Mary Shelley's account of when the idea came to her.

- ^ ”But for his incitement it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world”. Quoted by Holmes, 331, from Mary Shelley’s introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 30–31; Sunstein, 124.

- ^ Sunstein, 117.

- ^ Sunstein, 124–25; Seymour, 165.

- ^ St Clair, 413; Seymour, 175.

- ^ Mary Godwin wrote: "I long more than ever that our house should be quickly ready for the reception of those dear children whom I love so tenderly then there will be a sweet brother and sister for my William". Quoted in Spark, 54.

- ^ Sunstein, 129; St Clair, 414–15; Seymour, 176. Percy Shelley called the marriage a “nominal union”.

- ^ Spark, 54–55; Seymour, 176-77.

- ^ Spark, 57; Seymour, 177. Alba was renamed "Allegra" in 1818.

- ^ Spark, 58; Bennett, An Introduction, 21–22. The court based its decision against Shelley "upon the fact that in his case immoral opinions had led to conduct that the court was bound to consider immoral", and that he would "inculcate similar opinions and conduct in his children".

- ^ Seymour, 185; Sunstein, 136–37. Mary Shelley described their household as "very political as well as poetical". Percy Shelley wrote his major poem The Revolt of Islam at Marlow.

- ^ Seymour, 195-96.

- ^ Spark, 60–62; St Clair, 443; Sunstein, 143–49; Seymour, 191–92.

- ^ St Clair, 445.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 39–42; Spark, 62–63; Seymour, 205–6. Claire Clairmont agreed to Byron's terms against her better judgement, to provide Allegra with a better future.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 43. At various times, the Shelleys lived at Livorno, Bagni di Lucca, Venice, Este, Naples, Rome, Florence, Pisa, Bagni di Pisa, and San Terenzo.

- ^ Seymour, 214–16; Bennett, An Introduction, 46. Clara died of dysentery at the age of one, and William of malaria at three and a half.

- ^ Sunstein, 170–71, 179–82, 191.

- ^ Quoted in Seymour, 233.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 47, 53.

- ^ Spark, 72.

- ^ Sunstein, 384–85.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 115.

- ^ Seymour, 251.

- ^ Bieri, 170–76; Seymour, 267–70, 290; Sunstein, 193–95, 200–1.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 43–44; Spark, 77, 89–90; Gittings and Manton, 61–62. The Williamses were not technically married; Jane was still the wife of an army officer called Johnson.

- ^ St Clair, 318.

- ^ Holmes, 464; Bieri, 103–4. Their one visitor was a physician called Roskilly.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 46.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 46; Seymour, 221–22.

- ^ Spark, 73; Seymour, 224; Holmes, 469–70.

- ^ Journals, 249–50 n3; Seymour, 221; Holmes, 460–74; Bieri, 103–12. Elise had been employed by Byron as Allegra's nurse. Mary Shelley stated in a letter that Elise was pregnant by Paolo at the time, which was the reason they had married, but not that she had a child in Naples. Elise seems to have first met Paolo only in September. See Mary Shelley's letter to Isabella Hoppner, 10 August 1821, Selected Letters, 75–79.

- ^ Seymour, 221; Spark, 86; Letter to Isabella Hoppner, 10 August 1821, Selected Letters, 75–79.

- ^ Seymour, 221.

- ^ "Establishing Elena Adelaide's parentage is one of the greatest bafflements Shelley left for his biographers." Bieri, 106.

- ^ Seymour, 221.

- ^ Holmes, 466; Bieri, 105.

- ^ Spark, 79; Seymour, 292. In March 1821, busy at Ravenna with his new mistress Countess Teresa Guiccioli, Byron had broken his promise to keep Allegra with him and had placed her in a convent.

- ^ Seymour, 301. Holmes, 717; Sunstein, 216. Percy Shelley reported in May that Mary suffered "terribly from languor and hysterical affections".

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 71.

- ^ Holmes, 725; Sunstein, 217–218; Seymour, 270-73. Mary Shelley was slow to recover from her miscarriage: by the beginning of July, she was just able to "crawl from my bedroom to the terrace". See letter to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1822, Selected Letters, 98.

- ^ Seymour, 267-69.

- ^ Gittings and Manton, 71; Holmes, 715.

- ^ Seymour, 283-84, 298.

- ^ Holmes, 728.

- ^ Seymour, 298. One of three hands who had sailed the Don Juan down to Lerici from Genoa, Vivian had stayed on to crew the boat for Percy Shelley.

- ^ Letter to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1815, Selected Letters, 99.

- ^ Letter to Maria Gisborne, 15 August 1815, Selected Letters, 99.

- ^ Seymour, 302–07.

- ^ Qtd. in Seymour, 319.

- ^ Spark, 100–04.

- ^ Spark, 102–03; Seymour, 321-22.

- ^ Spark, 106–07; Seymour, 336-37.

- ^ Seymour, 362. In 1829, he raised it to £300 a year (Seymour 402).

- ^ Spark, 108.

- ^ Spark, 116, 119. The gist of Jane Williams's gossip was that Percy Shelley had preferred her to Mary in the last weeks of his life, owing to Mary's limitations as a wife.

- ^ Seymour, 341, 363-65.

- ^ Spark, 111–13; Seymour, 370-71.

- ^ Seymour, 543.

- ^ Spark, 117–19. Dods, who had an infant daughter, assumed the name Walter Sholto Douglas and was accepted in France as a man. These events did not come to light until the publication of Betty T. Bennett's edition of Mary Shelley's letters, 1980–83.

- ^ Seymour, 384–85.

- ^ Seymour, 389-90.

- ^ Seymour, 404, 433-35, 438.

- ^ Seymour, 406.

- ^ Seymour, 450, 455.

- ^ Seymour, 453.

- ^ Seymour, 465.

- ^ See Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters, xx, and Mary Shelley's letter of 24 May 1828, with Bennett's note, 198–99.

- ^ Spark, 122.

- ^ Seymour, 401-02, 467–68.

- ^ Spark, 133–34; Seymour, 424-26; Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters, xx. Beauclerk married Ida Goring in 1838 and, after Ida's death, Mary Shelley's friend Rosa Robinson in 1841. A clear picture of Mary Shelley's relationship with Beauclerk is difficult to reconstruct from the evidence.

- ^ Spark, 124; Seymour, 424.

- ^ Spark, 127; Seymour, 429, 500-01.

- ^ Seymour, 489.

- ^ Spark, 138.

- ^ Seymour, 495.

- ^ Qtd. in Spark, 139.

- ^ "Even now I can scarcely believe all is well," Mary Shelley wrote, "—my letters, my stupid nonsensical letters really rescued." Spark, 140; Seymour, 506-07.

- ^ Spark, 141–42; Seymour, 508-10.

- ^ Seymour, 515–16; Bieri, 112. According to Bieri, Medwin claimed to possess materials relating to Naples. Medwin is the source for the theory that the child registered by Percy Shelley in Naples was his daughter by a mystery woman. See also, Journals, 249–50 n3.

- ^ Qtd. in Spark, 143.

- ^ Sunstein, 383–84. The Shelleys left William Godwin's second wife, Mary Jane, buried in St Pancras churchyard.

- ^ Spark, 143; Seymour, 528.

- ^ Spark, 144; Bennett, Introduction to Selected Letters, xxvii.

- ^ Seymour, 540. Jane Shelley gave this explanation years later.

- ^ Sunstein, 384–85.

- ^ Bennett, "Mary Shelley's letters", 212–13.

- ^ "It is not singular that, as the daughter of two persons of distinguished literary celebrity, I should very early in life have thought of writing. As a child I scribbled; and my favourite pastime, during the hours given me for recreation, was to 'write stories'." Mary Shelley, Introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, Longman edition of Frankenstein, 186–89.

- ^ Sussman, 163; St Clair, 297; Sunstein, 42.

- ^ Seymour, 55; Carlson, 245.

- ^ Seymour, 59; Sunstein, 56.

- ^ Quoted in Wolfson, Introduction to Frankenstein, xvii.

- ^ Seymour, 187. Mary Shelley was responsible for rewriting and editing the journal for publication.

- ^ Moskal, "Travel writing", 242.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 24–29.

- ^ Moskal, "Travel writing", 244; Clemit, "Legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft", 30.

- ^ Seymour, 190, 195; Wolfson, Introduction to Frankenstein, xix.

- ^ Spark, 154.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 30–31.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 36–42.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 35; Mellor, "Making a 'monster' ", 11, 23.

- ^ Gilbert and Gubar, 223.

- ^ Gilbert and Gubar, 220.

- ^ Poovey, 115-16, 126-27.

- ^ Poovey, 131.

- ^ Poovey, 124-25.

- ^ Smith, "A Critical History of Frankenstein",

- ^ Poovey, 133ff.

- ^ Seymour, 335; Peake's stage version, called Presumption; or The Fate of Frankenstein, is printed in the Longman Cultural Edition of Frankenstein, ed. Susan J. Wolfson, 323–68.

- ^ Seymour, 335.

• For a collection of popular contemporary allusions, see Susan J. Wolfson, "Frankentalk: Frankenstein in the Popular Press of Today", in the Longman Cultural Edition of Frankenstein, ed. Susan J. Wolfson, 402–24.

• "Naming the creature 'Frankenstein'—as popular folklore would have it—uncovers a profound truth within the novel's narrative." Mellor, "Making a 'monster' ", 23; see Spark, 161, and Wolfson,"Frankentalk", 402, on the same point. - ^ Smith, "A Critical History of Frankenstein", 189-90.

- ^ Smith, "A Critical History of Frankenstein", 194, 197.

- ^ Smith, "A Critical History of Frankenstein", 199.

- ^ Clemit, "Legacies of Godwin and Wollstonecraft", 37. Mary Shelley spelled the novel's title "Matilda" and the heroine's name "Mathilda". The book has been published under each title.

- ^ Todd, Introduction to Matilda, xxii; Bennett, An Introduction, 47. During this period, Percy Shelley dramatised an incestuous tale of his own,The Cenci.

- ^ For example, Nitchie, Introduction to Mathilda, and Mellor, Mary Shelley, 143.

- ^ Clemit, "From The Fields of Fancy to Matilda ", 64–75.

- ^ Nitchie, Introduction to Mathilda.

- ^ Todd, Introduction to Matilda, xvii.

- ^ Nitchie, Introduction to Mathilda.

- ^ Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xv; Curran, Introduction to Valperga, xxiv–xxv. Godwin changed the title from Castruccio, Prince of Lucca, to point up the central dilemma of the book; but the nature of his changes to the text is unknown—editor Stuart Curran suggests they cannot have been major. Mary Shelley had given Godwin the rights to the book, to help him with his financial problems.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 60–61.

- ^ Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xi; Curran, Introduction to Valperga, xxi.

- ^ Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xii.

- ^ Curran, Introduction to Valperga, xviii, xxiii.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 60.

- ^ Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, x, xii–xv; Curran, Introduction to Valperga, xix. Mary Shelley, as Percy Shelley confirmed, "visited the scenery which she described in person", and consulted many books about Castruccio and his times.

- ^ Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xxiv.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 61.

- ^ Sussman, "Stories for The Keepsake", 163–65.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 72.

- ^ Paley, Introduction to The Last Man, viii, xxii.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 74. Mary Shelley privately confirmed these "faint portraits".

• News of Byron's death in Greece reached Mary Shelley at an early stage in the writing the novel. On 15 May 1824, she wrote in her journal: "Byron has become one of the people of the grave, that miserable conclave to which the beings I best loved belonged". Bickley, "Introduction to The Last Man, xvii; Paley, "Introduction to The Last Man, xvii–xviii. - ^ Paley, Introduction to The Last Man, viii. Mary Shelley used this term in a letter of 3 October 1824.

- ^ Bickley, Introduction to The Last Man, xii, xiv.

• "The last man!" Mary Shelley wrote in her journal in May 1824. "Yes I may well describe that solitary being's feelings, feeling myself the last relic of a beloved race, my companions extinct before me". Paley, Introduction to The Last Man, vii–viii. - ^ Paley, Introduction to The Last Man, xvi; Lokke, "The Last Man", 117.

- ^ Lokke, "The Last Man", 128–29.

- ^ Paley, Introduction to The Last Man, xxi.

- ^ Paley, "Introduction to The Last Man, xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 73.

- ^ Frank, "Perkin Warbeck".

- ^ Spark, 201. Mary Shelley consulted Scott while writing the book.

- ^ "It is not singular that I should entertain a belief that Perkin was, in reality, the lost Duke of York . . . no person who has at all studied the subject but arrives at the same conclusion." Mary Shelley, Preface to Perkin Warbeck, vi–vii, quoted in Bunnell, 131.

- ^ Bunnell, 132; Brewer, "Perkin Warbeck".