Jim and Mary McCartney: Difference between revisions

→Paul and Michael: dor rhone and her miscarriage |

|||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

After Mary's death Paul and Michael were sent to live with Jim's brother Joe McCartney and his wife Joan's house for a short time, so as to let their father grieve in private.<ref name="MilesPage20"> Miles 1998 p20.</ref> Jim depended heavily on his sisters, Jin and Millie, to help around the house, as Jim was so depressed he once threatened suicide, so Jin became the motherly aunt to the distraught McCartney family.<ref name="Spitzp91"> Spitz 2005 p91.</ref> Jim later took part in the running of the household, as [[Cynthia Lennon]] remembered that when she and [[John Lennon]] used to visit Forthlin Road, Jim would often answer the door with his sleeves rolled up, a [[tea towel]] in his hand and an [[apron]] tied around his waist. While Jim was in the kitchen, Lennon and Paul would write songs in the front room until Jim called them for [[Tea (meal)|tea]].<ref name="CynthiaJohnp47"> Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p47</ref> When Paul later played at [[The Cavern]] during lunchtime, Jim would drop off some food there that Paul would put in the oven at Forthlin Road, so as to be ready to eat in the evening.<ref name="CynthiaJohnp87"> Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p87</ref> |

After Mary's death Paul and Michael were sent to live with Jim's brother Joe McCartney and his wife Joan's house for a short time, so as to let their father grieve in private.<ref name="MilesPage20"> Miles 1998 p20.</ref> Jim depended heavily on his sisters, Jin and Millie, to help around the house, as Jim was so depressed he once threatened suicide, so Jin became the motherly aunt to the distraught McCartney family.<ref name="Spitzp91"> Spitz 2005 p91.</ref> Jim later took part in the running of the household, as [[Cynthia Lennon]] remembered that when she and [[John Lennon]] used to visit Forthlin Road, Jim would often answer the door with his sleeves rolled up, a [[tea towel]] in his hand and an [[apron]] tied around his waist. While Jim was in the kitchen, Lennon and Paul would write songs in the front room until Jim called them for [[Tea (meal)|tea]].<ref name="CynthiaJohnp47"> Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p47</ref> When Paul later played at [[The Cavern]] during lunchtime, Jim would drop off some food there that Paul would put in the oven at Forthlin Road, so as to be ready to eat in the evening.<ref name="CynthiaJohnp87"> Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p87</ref> |

||

Shortly after Paul returned from Hamburg in May 1962, Dot Rhone (Paul's first serious girlfriend in Liverpool) told him that she was pregnant. They told Jim—whom they expected to be shocked at the news—but found him delighted at the prospect of becoming a grandfather, and also because he was lonely after Mary's death. (Rhone later lost the baby after a [[ |

Shortly after Paul returned from Hamburg in May 1962, Dot Rhone (Paul's first serious girlfriend in Liverpool) told him that she was pregnant. They told Jim—whom they expected to be shocked at the news—but found him delighted at the prospect of becoming a grandfather, and also because he was lonely after Mary's death. (Rhone later lost the baby after a [[miscarriage]]).<ref name="Spitzp319-320"> Spitz 2005 pp319-320</ref> |

||

62-year-old Jim was earning £10 a week in 1964, but Paul suggested that his father should retire, and bought "Rembrandt"—a detached mock-tudor house in Baskervyle Road, [[Heswall]], [[Cheshire]]—for £8,750.<ref name="MilesPage210"> Miles 1998 p210.</ref><ref>[http://magicalbeatletours.com/tour_wirral.htm#rembrandt Photo of Rembrandt] magicalbeatletours.com - Retrieved 22 October 2007 </ref> Paul also bought Jim a horse called "Drake’s Drum". A couple of years later, after the horse had won the race immediately preceding the [[Grand National]], Paul led the horse into the winner’s enclosure at [[Aintree]].<ref name="HarryBeatlesEncyclopedia"> Harry 2001 - The Beatles’ Encyclopedia</ref><ref name="beatlesireland">[http://www.iol.ie/~beatlesireland/zBeatlesfactfiles/factfilesx1/TheMcCartneys/JamesMcCartney(Father).htm Jim McCartney biog] beatlesireland - Retrieved: 6 October 2007 </ref> |

62-year-old Jim was earning £10 a week in 1964, but Paul suggested that his father should retire, and bought "Rembrandt"—a detached mock-tudor house in Baskervyle Road, [[Heswall]], [[Cheshire]]—for £8,750.<ref name="MilesPage210"> Miles 1998 p210.</ref><ref>[http://magicalbeatletours.com/tour_wirral.htm#rembrandt Photo of Rembrandt] magicalbeatletours.com - Retrieved 22 October 2007 </ref> Paul also bought Jim a horse called "Drake’s Drum". A couple of years later, after the horse had won the race immediately preceding the [[Grand National]], Paul led the horse into the winner’s enclosure at [[Aintree]].<ref name="HarryBeatlesEncyclopedia"> Harry 2001 - The Beatles’ Encyclopedia</ref><ref name="beatlesireland">[http://www.iol.ie/~beatlesireland/zBeatlesfactfiles/factfilesx1/TheMcCartneys/JamesMcCartney(Father).htm Jim McCartney biog] beatlesireland - Retrieved: 6 October 2007 </ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:11, 23 October 2007

James "Jim" Paul McCartney & Mary Patricia McCartney | |

|---|---|

| File:Paul and Jim McCartney.jpg Paul and Jim McCartney in the early 1970s | |

| Born | Jim: 7 July 1902 Mary: 29 September 1909 Liverpool |

| Died | Jim: 18 March 1976 Mary: 31 October 1956 Liverpool |

| Occupation(s) | Jim: Cotton Salesman Mary: Nurse, Matron, and Midwife |

| Spouse(s) | Jim: Mary Mohan and Angela Williams |

| Children | James Paul McCartney, Peter Michael McCartney, and Ruth Williams (adopted) |

| Parent(s) | Jim: Joe & Florence McCartney (née Clegg) Mary: Owen & Mary Theresa Mohan (née Danher) |

James "Jim" McCartney and Mary Patricia McCartney (née Mohan) are the (deceased) parents of musician, author, and artist Paul McCartney, best known for his work in The Beatles and Wings, and photographer and musician Mike McCartney, who worked with The Scaffold.

Jim worked for most of his life in the cotton trade, and Mary was a trained nurse and midwife. They lived in rented property throughout their life together. Like many families in Liverpool, the McCartneys and the Mohans are from Irish descent.

Jim came from a musical background and encouraged his two sons to take up music, as well as improving their status in life through education. Mary was a warm and caring mother, but her untimely death deeply affected the whole of the family. Mary was Paul's inspiration for the song, "Let It Be".

McCartney & Mohan

The McCartneys have Irish roots, as Jim's great-grandfather, James McCartney (an upholsterer) was born in Ireland, but it is unknown if Jim's grandfather, James McCartney II, was born in England, or Ireland.[1] James II—a plumber and painter—married Elizabeth Williams in 1864. The pair were both under-age when they got married, but found a place to live together in Scotland Road, Liverpool.[2] Joseph "Joe" McCartney (Jim's father, b. 23 November 1866) was a tobacco cutter by trade when he married Florence "Florrie" Clegg (b. 2 June 1874) in the Christ Church, Kensington, Liverpool, on 17 May 1896.[3][4] Although deeply interested in music, Joe never drank alcohol, went to bed at 10 o’clock every night, and the only swear word he used was ‘Jaysus’. Florrie was known as "Granny Mac" in the neighbourhood, and was often consulted when families had problems.[2]

Mary's father's birth name was Owen Mohin—but permanently changed his name to Mohan when he was at school to avoid confusion with many other pupils called Mohin—and was born in Tullynamalrow, County Monaghan, Ireland, in 1880. He was working as a coalman when he married Mary Theresa Danher from Toxteth Park, at St. Charles Roman Catholic Church, Toxteth Park, on 24 April 1905.[5]

Jim

James 'Jim' McCartney was born at 8 Fishguard Road, Everton, Liverpool, and was the eldest of nine children: James (Jim), Edith, Ann, Alice, Millie, Jack, Ann, Jean (Jin), and Joe (who was named after the second-eldest brother who had died in infancy).[6] The McCartney family moved shortly after Jim's birth to 3 Solva Street in Everton, which was a run-down terraced house about three-quarters of a mile from the Liverpool city centre, and where Jim attended the Steers Street Primary School off Everton Road.[6][7]

After leaving school at 14, Jim found work for six shillings a week as a cotton "sample boy" at A. Hanney & Co. - a cotton broker in Chapel Street, Liverpool.[8][9] Jim's job entailed running up and down Old Hall Street with large bundles of cotton that had to be delivered to cotton brokers or merchants in various salesrooms. He worked ten-hour days, for five days a week, and was paid less than £1, although he received a bonus at Christmas that was almost double his annual salary.[10]

When World War II started Jim was too old to be called up for active service—as well as having previously been disqualified on medical grounds after falling from a wall and smashing his left eardrum when he was 10-years-old.[5][11] After the cotton exchange closed for the duration of the war, Jim worked as a lathe-turner at Napier's engineering works where he made shell cases that were later filled with explosives.[12] He also volunteered to be a fireman at night, and often watched Liverpool burning uncontrollably from his rooftop observer's position when not actually fighting fires. (Between 1940 and 1942, Liverpool endured 68 air-raids, which killed or injured more than 4,500 of Liverpool's population and destroyed more that 10,000 homes).[5][13][14] After the war Jim worked for a short time as an inspector for Liverpool Corporation's Cleansing Department before returning to the cotton trade in 1946.[15]

Jim liked to "match his wits" against most people he knew, avidly read the Liverpool Echo or Express, and loved to instigate lively discussions about a whole range of subjects. His attitude to life was based upon self-respect, perseverance, fairness, and a strong work ethic.[16] Although living in a council house and working for a low wage, Jim's political views were far from left-wing. He had long conversations with Ted Merry—his sister Jean's husband—who argued for the rights of workers, but Jim insisted that there was nothing anyone could do about the situation the working classes were in, and nothing would ever change.[8]

Jim died of bronchial pneumonia on 18 March 1976.[17] His second wife, Angela McCartney (née Williams) said that his last words were, "I’ll be with Mary soon."[18] Jim died two days before a Wings European tour, and Paul did not attend the funeral.[19] Jim was cremated at Landican Cemetery, near Heswall, on 22 March.[20]

Mary

Mary Patricia Mohan was born at 2 Third Avenue, Fazakerley, Liverpool. When Mary was 11-years-old, her mother, Mary Theresa Mohan, died giving birth to a fourth child (a daughter) who also died.[11][21]

After two years Mary's father met and married his second wife, Rose, whilst on a trip to Monoghan, in Ireland.[22] Rose arrived in Liverpool with two children from a previous marriage, and the young Mary (who had until then been looking after the Mohan family) realised that Rose did not care much for domesticity or her new husband's children. Mary did not take to her new Irish mother, and after a year she chose to live with her aunts.[11] In 1923, at 14-years-old, Mary started her training to become a nurse at the Alder Hey Hospital. She later transferred to Walton Road Hospital in Rice Lane, Liverpool, and after ten years she reached the position of Matron.[11][23]

Mary rode a bicycle to houses where she was needed as a midwife, and Paul's earliest memory is of her leaving 72 Western Avenue at night when it was snowing heavily, in a navy-blue uniform and hat.[24] Even after she had been diagnosed with cancer Mary still carried on working, even though she was often doubled up in pain and had trouble breathing, but never complained.[25][26] The day Mary was due to go to hospital to have a mastectomy operation, she cleaned the whole house and laid Paul and Michael's school clothes out ready for the next day. She said to Dill Mohan (her sister-in-law)

Now everything's ready for them - in case I don't come back.[27]

Mary McCartney died of an embolism on 31 October 1956, after the mastectomy operation to stop the spread of her breast cancer. Her last words to Dill Mohan were,

I would love to have seen the boys [Paul and Michael] growing up.

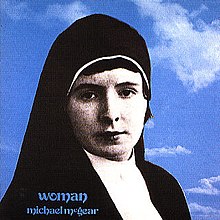

Mary was buried on 3 November 1956 at Yew Tree Cemetery, Finch Lane, Liverpool.[28][29] Paul later named his daughter Mary after his mother, and Michael released an album entitled Woman in 1972—including the song, "Woman"—with a photo of Mary on the front cover.[2][30]

Marriage

Mary met her future husband during an air raid on Liverpool in 1940, when Jim was 40-years-old, and had settled into what his friends thought was, "a confirmed bachelorhood". Mary had also been too immersed in her work and career-conscious to think of marriage, and at 31-years-old, was thought of as a spinster.[31]

They met in June 1940, at the McCartney family home at 11 Scargreen Avenue, West Derby, as the family had gathered to celebrate the wedding of Jim's sister Jin to Harry Harris. Mary was there because she was staying with the Harris family, but with her wavy, unruly hair, and a distracted look in her eyes, nobody noticed her as she sat quietly in an armchair.[32] This carried on until the air-raid sirens sounded at 9:30, and everyone went down to the cellar to wait for the all-clear, which was usually after an hour or so. That night there was an intensive bombing raid, so everyone was forced to sit in the cellar until dawn. In those unromantic surroundings, Mary talked long enough with Jim to become romantically interested in him, and thought that he was "utterly charming and uncomplicated," as well as being entertained by his "considerable good humour."[31]

Jim and Mary took out a licence at the Liverpool Town Hall on 8 April 1941, and were married a week later at St. Swithin’s Roman Catholic chapel in Gillmoss, West Derby, on 15 April 1941.[33] Although they first lived at 10 Sunbury Road, Liverpool, they lived for a short time at 92 Broadway, Wallasey, in November 1942. Jim's job at Napiers was classified as war work, so the McCartneys were given a small, but temporary, prefab house at 3 Roach Avenue, Knowsley.[34]

Mary became a domiciliary health visitor and midwife, forcing her to be on-call at all hours of any day or night, but her income allowed the McCartneys to move to a ground-floor flat at 75 Sir Thomas White Gardens, off St. Domingo Road in Everton, to live in a rent-free flat that was supplied by Mary's employers.[34][15] They moved again shortly after—in February 1946—to 72 Western Avenue in Speke.[35][36]

In 1948, the family moved to 12 Ardwick Road (also in Speke) which was part of a new estate in the suburbs of Liverpool.[34][37] Paul remembered lots of mud on the unfinished roads and the feeling of being "on the edge of the world, like Christopher Columbus".[38][39] The frequent moves to better areas was always Mary's idea, as she wanted to raise her children in the best possible neighbourhood.[40]

In 1955, the McCartney family moved—for the last time—to a small three-bedroomed brick-built terrace house at 20 Forthlin Road in Allerton, which is now owned by The National Trust.[41][42][43] It was considered to be in a slightly posh area, but only cost £1.6 shillings a week, thanks to Mary's seniority at the hospital.[44] Before moving to Forthlin Road, Jim had been the secretary of the Speke Horticultural Society, and often sent Paul and Michael out to canvass for new members.[45] At Forthlin Road Jim planted dahlias and snapdragons in the front garden and regularly trimmed the lavender hedge, although it was Paul's job to collect horse manure from the local streets in a bucket to be dug into the flowerbeds. As both Jim and Mary were heavy smokers, Jim would first dry and then crush sprigs of lavender, and then burn them (like incense) in the ashtrays to kill the smell of cigarette smoke.[45]

Money was always a problem in the McCartney house, as Jim only earned up to £6.00 a week, which was less than his wife.[34] Because of this the McCartney family could not afford to buy a television set until Queen Elizabeth II's coronation in 1953, and never owned a car—Paul and Michael were the first to buy cars.[24][46]

Jim eventually had to leave Forthlin Road because fans of The Beatles used to constantly hang around outside and stare through the windows, which made Jim feel uncomfortable and nervous.[47]

Second marriage

Eight years after Mary's death, Jim married the widow Angela Williams—after only meeting her three times—on 24 November 1964. (Jim was 62-years-old and Angie 34-years-old when they got married).[48] They were introduced by Jim's niece, Bette Robins. Angela had a daughter, Ruth, who was legally adopted by Jim—becoming Paul and Michael's step-sister.[18]

Children

Although Jim and Mary McCartney had children late in their lives—later than was usual according to the attitude at the time—they were respected by their children as loving parents, although both Jim and Mary taught their children discipline and respect for others. They encouraged their children to grow musically as well as intellectually, and concentrated on making sure they grew up in a family-oriented household.

Paul and Michael

Paul McCartney (b. 18 June 1942) and Michael McCartney (b. 7 January 1944) were both delivered in the Walton General Hospital in Liverpool, where Mary had previously worked as a nursing sister in charge of the maternity ward.[49] Mary was welcomed back—when she gave birth to Paul—by being given a bed in a private ward.[5][50] Jim was not present at the birth as he was fighting a warehouse fire at the back of the Martin's bank building, but arrived at the hospital two hours later.[33][51]

As Mary was a Roman Catholic and Jim a Church of England Protestant—who later turned agnostic—their children were baptized Roman Catholic but raised non-denominationally. (Mary had married Jim on the promise that any children would be baptised in the Catholic faith). Although baptised as James Paul McCartney, the McCartney's first son was known as Paul from the day he was first taken home.[15] Paul and Michael were not enrolled in Catholic schools as Jim believed that they leaned too much towards religion instead of education.[5]

Paul remembers his mother as being a very caring person and having a strong sense of humour, and encouraging her children to use the Queen's English and not the Liverpudlian dialect.[16][52] Paul regretted once laughing at his mother for saying the word 'ask' in a posh/refined accent.[31][40] Michael remembered that Jim had a temper when he was provoked, and that both Paul and he were "duly bashed" (hit) when they were young. This is refuted by other members of the family, who say that Jim or Mary never smacked them, but took them to their rooms and gave them "a good talking-to".[53]

Jim and Mary would often take Paul and Michael for a walk to the local rustic village of Hale (home of the giant Childe of Hale's gravesite) and stop on the way home for tea, Hovis toast and jam at the Elizabethan Cottage teashop. According to Paul, these frequent trips out of Liverpool to the countryside inspired his love of nature, as well as being in the Boy Scouts, which involved Birdwatching.[54][55]

The McCartneys had higher aspirations than most other people living in Allerton. They had a full set of George Newnes Encyclopedias which Jim encouraged Paul and Michael to use, and as Jim was avidly interested in solving crossword puzzles he told his sons to look up any word they did not understand.[56] After Paul had passed the eleven-plus exam—meaning he would automatically gain a place at the prestigious Liverpool Institute—Mary hoped Paul would become a doctor or a teacher, and Jim hoped Paul would go to university, and later become "a great scientist" (Michael would also attend the Liverpool Institute two years later). Paul later joked that judging by his parents' expectations, he was an "over-achiever".[57]

After Mary's death Paul and Michael were sent to live with Jim's brother Joe McCartney and his wife Joan's house for a short time, so as to let their father grieve in private.[28] Jim depended heavily on his sisters, Jin and Millie, to help around the house, as Jim was so depressed he once threatened suicide, so Jin became the motherly aunt to the distraught McCartney family.[58] Jim later took part in the running of the household, as Cynthia Lennon remembered that when she and John Lennon used to visit Forthlin Road, Jim would often answer the door with his sleeves rolled up, a tea towel in his hand and an apron tied around his waist. While Jim was in the kitchen, Lennon and Paul would write songs in the front room until Jim called them for tea.[59] When Paul later played at The Cavern during lunchtime, Jim would drop off some food there that Paul would put in the oven at Forthlin Road, so as to be ready to eat in the evening.[60]

Shortly after Paul returned from Hamburg in May 1962, Dot Rhone (Paul's first serious girlfriend in Liverpool) told him that she was pregnant. They told Jim—whom they expected to be shocked at the news—but found him delighted at the prospect of becoming a grandfather, and also because he was lonely after Mary's death. (Rhone later lost the baby after a miscarriage).[61]

62-year-old Jim was earning £10 a week in 1964, but Paul suggested that his father should retire, and bought "Rembrandt"—a detached mock-tudor house in Baskervyle Road, Heswall, Cheshire—for £8,750.[62][63] Paul also bought Jim a horse called "Drake’s Drum". A couple of years later, after the horse had won the race immediately preceding the Grand National, Paul led the horse into the winner’s enclosure at Aintree.[48][64]

Ruth

Ruth McCartney remembered that Jim was funny and musical with her, but also strict when she was young, and was insistent that she learned good table manners and etiquette when speaking to people.[65] Ruth revealed that Paul smoked marijuana in the Rembrandt house, which Jim fervently disagreed with, but Paul smoked it anyway, as he had paid for the house.[66]

Ruth now controls "McCartney.com", which presents information about Paul McCartney and his family, although not officially endorsed by him.[67][68] Ruth's mother, Angela, has no contact with Paul, as she sold his birth certificate. Paul complained:

She then sold my original birth certificate without saying anything to me or letting me know that she was putting it up for sale at auction - so some bugger has got my birth certificate now and I don’t know who it is.[69]

Music

Joe McCartney, Jim's father, was a traditionalist who loved opera and played an E-flat tuba in the local Territorial Army band that played in Stanley Park, and the Copes' Tobacco factory Brass Band where he worked.[10] He also played the double bass at home, had a good singing voice, and hoped to interest his children in music.[70] Being the only member of the family to take an interest in music, Jim learned how to play the trumpet and piano by ear, and at the age of 17 started playing ragtime music. Joe McCartney thought ragtime (the most popular music at the time) was "tin-can music". Jim's first public appearance was at St Catherine’s Hall, Vine Street, with a band that wore black masks, as a gimmick, calling themselves the "Masked Melody Makers". He later led Jim Mac's Jazz Band in the 1920s (with his brother Jack on trombone) and composed his first tune, Eloise.[71] Paul would later put words to Jim's tune and record it as, Walking in The Park With Eloise.[48][64] (The song—with B-side, Bridge Over The River Suite—was released on a 1974 single by the "Country Hams", which featured Wings, Floyd Cramer and Chet Atkins.[72]

Jim had a collection of old, scratched 78 rpm records that he would often play, or play his musical "party-pieces" (hits of the time) on the piano in the front room.[73] He used to point out the different instruments in songs on the radio to his two sons, and often took them to local brass band concerts. This early influence would later lead Paul to work with the Black Dyke Mills Band.[74]

Jim also taught his young boys a basic idea of harmony between instruments, and Paul credits Jim's tuition as being a great help when he later sang harmonies with Lennon.[73][75]

Jim had an upright piano in the Forthlin Road front room that he had bought from Harry Epstein's North End Music Store (NEMS). Harry Epstein's son, Brian Epstein, would later become The Beatles manager.[75][76] With encouragement from Jim, Paul started playing the McCartneys' piano and wrote "When I'm Sixty-Four" on it.[77] Jim advised Paul to take some music lessons, which he did, but Paul soon realised that he preferred to learn 'by ear' (as his father had done) and because he never paid attention in music classes.[77][78] McCartney commented on what happened during music lessons:

The music lessons were awful; they consisted solely of the teacher leaving us in a room to listen to music. The students used to turn it down and tell jokes.[49]

After Mary's death, Jim gave Paul a nickel-plated trumpet, but when skiffle music became popular, McCartney swapped the trumpet for a £15 Framus Zenith (model 17) acoustic guitar—which he still owns. This was because Paul soon realised that he couldn't sing and play at the same time.[79][80] Paul also played his father's Framus Spanish guitar when writing early songs with Lennon.[81] After Paul and Michael became interested in music, Jim connected the radio in the living room to extension cords connected to two pairs of Bakelite headphones so that they could listen to Radio Luxembourg at night when they were in bed.[74]

After meeting Lennon, Jim warned Paul that he would get him "into trouble", although he later allowed The Quarrymen to rehearse in the dining room at Forthlin Road in the evening. Jim didn't know that Lennon was writing songs in the afternnon with Paul when they were both supposed to be in school.[82][83] Wanting to help Paul's career, Jim arranged a concert—which only Paul and George Harrison played at—in February 1960, at the Working Men's Club he frequented.[73] Jim was reluctant to let the teenage Paul go to Hamburg with The Beatles until Paul pointed out that he would earn £2.10 shillings per day. As this was more than he earned himself, Jim finally agreed, but only after a visit from the group's then-manager, Allan Williams (who was economical with the truth about Hamburg) who said that Jim shouldn't worry.[84][85]

Jim was present at a Beatles' concert in Manchester when fans surrounded drummer Pete Best, and ignored the rest of The Beatles. Jim criticised Best by saying,

Why did you have to attract all the attention? Why didn't you call the other lads back? I think that was very selfish of you.[86]

Bill Harry recalled that Jim was probably "The Beatles' biggest fan", and was extremely proud of Paul's success. Shelagh Johnson—later to become director of The Beatles' Museum in Liverpool—said that Jim's outward show of pride embarrassed his son, but thought that Paul secretly enjoyed it.[87] Jim enlisted Michael's help when sorting through the ever-increasing sacks of fan letters that were delivered to Forthlin Road, with both composing "personal" responses from Paul.[88] Michael would later have success on his own with the group The Scaffold.[89]

Songs

Paul wrote "I Lost My Little Girl" ⓘ just after Mary had died, and said that it was probably a subconscious reference to his late mother.[80] Paul wrote "We Can Work It Out" and "Golden Slumbers" ⓘ at his father's house in Cheshire.[62][90] Some of the lyrics for "Golden Slumbers" were taken from Ruth McCartney's sheet-music copy of Thomas Dekker's lullaby—also called "Golden Slumbers"—that Ruth had left on the piano at Rembrandt. As Paul couldn't read the music, he composed his own version by using some of the original lyrics.[90]

Hunter Davies—who was at Jim's house at the time doing an interview for his Beatles' biography—remembered Paul sending an acetate disc of "When I'm 64" Audio file " Beatles sixty-four.ogg" not found for Jim to listen to (although the original melody had been written when Paul was 16-years-old).[91] Davies said that Paul had recorded it especially, as Jim was then 64-years-old and had married Angela two years previously.[92]

Michael recorded the song "Woman" Audio file " Woman Mike McGear.ogg" not found on his solo album—also called Woman—in 1972, which he dedicated to Mary. Paul mentioned Michael and Aunty Jean (Jim's sister) in his song for Wings, called, "Let 'em In", Audio file " Let Em In.ogg" not found by using her nickname; Aunty Jin.[93]

Paul wrote "Let It Be", Audio file " Beatles Let It Be.ogg " not found because of a dream he had during the Get Back/Let It Be sessions. He said that he had dreamt of his mother, and the "Mother Mary" lyric was about her.[49] He later said,

It was great to visit with her again. I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing 'Let It Be'.[28][48]

He also said—in a later interview about the dream—that his mother had told him,

It will be alright, just let it be.[94]

Notes

- ^ Miles 1998 p3.

- ^ a b c McCartney family biog – 6 June 2007 liverpoolecho.co.uk - Retrieved 5 October 2007

- ^ Miles 1998 p3-4

- ^ Spitz 2005 p18

- ^ a b c d e Miles 1998 p4.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005 p69

- ^ Spitz 2005 p70

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p12

- ^ Chapel Street, Liverpool google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ a b Spitz 2005 p71

- ^ a b c d Spitz 2005 p74 Cite error: The named reference "Spitzp74" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Robert Napier - The Father of Clyde Shipbuilding amostcuriousmurder.com - Retrieved 6 October 2007

- ^ Liverpool in the Second World War bbc.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ Air Raids in Liverpool bbc.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ a b c Spitz 2005 p76.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005 p82.

- ^ Miles 1998 p601

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p557

- ^ Paul did not attend the funeral therockradio.com - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ Landican Cemetery, near Heswall google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ 2 Third Avenue, Fazakerley, Liverpool google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ Info about Monoghan, Ireland monaghanlive.com - Retrieved 6 October 2007

- ^ Rice Lane google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p6.

- ^ Spitz 2005 pp88-89.

- ^ Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p46

- ^ Spitz 2005 p89.

- ^ a b c Miles 1998 p20.

- ^ Yew Tree Cemetery, Finch Lane, Liverpool google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ Michael McCartney’s solo album amazon.com - Retrieved 17 October 2007

- ^ a b c Spitz 2005 p73.

- ^ Spitz 2005 p72.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005 p75.

- ^ a b c d Miles 1998 p5.

- ^ Spitz 2005 p78.

- ^ 72 Western Avenue in Speke, Liverpool. google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ Miles 1998 p9.

- ^ Spitz 2005 p79.

- ^ 12 Ardwick Road in Speke, Liverpool. google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p15.

- ^ Photo of the back of Forthlin Road nationaltrust.org.uk - Retrieved: 27 January 2007

- ^ 20 Forthlin Road in Allerton, Liverpool google.co.uk/maps - Retrieved 4 October 2007

- ^ The Rough Guide to the Beatles google.com/books - Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^ Spitz 2005 p88.

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p8

- ^ Michael McCartney’s first car liverpoolmuseums.org.uk - Retrieved 7 October 2007

- ^ Jim was forced to leave Forthlin Road – 21 July 1998 bbc.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ a b c d Harry 2001 - The Beatles’ Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c Sir Paul McCartney - Singer/Songwriter - 19th January 2007 bbc.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ Spitz 2005 p75

- ^ Mike Royden's Local History Pages btinternet.com - Retrieved 7 October 2007

- ^ Miles 1998 p6

- ^ Spitz 2005 p80.

- ^ Miles 1998 p10.

- ^ Miles 1998 p29

- ^ Miles 1998 pp12-13.

- ^ Miles 1998 p12

- ^ Spitz 2005 p91.

- ^ Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p47

- ^ Cynthia Lennon “John” 2006 p87

- ^ Spitz 2005 pp319-320

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p210.

- ^ Photo of Rembrandt magicalbeatletours.com - Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^ a b Jim McCartney biog beatlesireland - Retrieved: 6 October 2007

- ^ Interview with Ruth McCartney classicbands.com - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ Marijuana in Rembrandt - 2 December 2006 dailymail.co.uk - Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^ McCartney.com web page detailing Paul McCartney’s activities mccartney.com - Retrieved 17 October 2007

- ^ Ruth McCartney’s web page mccartney.com - Retrieved 17 October 2007

- ^ Angela McCartney biog beatlesireland.utvinternet.com - Retrieved 17 October 2007

- ^ Miles 1998 p23.

- ^ Miles 1998 p22.

- ^ Wings At The Speed Of Sound, (CD) June 1993; Cat. number CDP78914027

- ^ a b c Spitz 2005 p85

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p24.

- ^ a b Miles 1998 pp23-24.

- ^ Spitz 2005 p71

- ^ a b Miles 1998 pp22-23.

- ^ McCartney never paid attention in music classes femalefirst.co.uk - Retrieved: 2 October 2006

- ^ Spitz 2005. p86

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p21.

- ^ Early guitars McCartney played thecanteen.com - Retrieved 27 January 2007

- ^ Miles 1998 pp32-38.

- ^ Inside ForthlinRoad nationaltrust.org.uk - Retrieved 12 November 2006

- ^ Miles 1998 p57.

- ^ Spitz 2005 p205

- ^ Spitz 2005. p322

- ^ Spitz 2005. p392

- ^ Spitz 2005. p410

- ^ The Scaffold biog biguntidy.com - Retrieved 8 October 2007

- ^ a b Miles 1998 p557.

- ^ Miles 1998 p319

- ^ ‘When I'm 64’ story guardian.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

- ^ Photo of Aunty Jin’s home beatlesource.com - Retrieved 6 October 2007

- ^ “sold on song” article bbc.co.uk - Retrieved 11 October 2007

References

- Davies, Hunter (1985). The Beatles. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-015463-5.

- Harry, Bill (Rev Upd edition 2001). The Beatles Encyclopedia. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 978-0753504819.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Lennon, Cynthia (2006). John. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-89828-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Martin, George and Pearson, William (1994 ). With a Little Help from My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper. Little, Brown . ISBN 0-316-54783-2.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miles, Barry (1998). Many Years From Now. Vintage-Random House. ISBN 0-7493-8658-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company (New York). ISBN 1-84513-160-6.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)

External Links

- Houses and places of interest in Liverpool.

- The Beatles' Fact Files

- The Beatles Ireland - Jim McCartney

- The Beatles Ireland - Mary McCartney

- The McCartneys' Irish Heritage