Irish language

| Irish | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | around 1.6 million as a second language, a maximum of 70,000 use the language daily (first language; estimates) | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

ga |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

gle ( loc.gov ) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

gle ( SIL , ethnologue ) |

|

The Irish language (Irish Gaeilge [ ˈɡeːlʲɟə ] or in the Munster dialect Gaolainn [ ˈɡeːləɲ ], according to the orthography valid until 1948 mostly Gaedhilge ), Irish or Irish-Gaelic , is one of the three Goidelic or Gaelic languages . They also include Scottish Gaelic and Manx (a language spoken on the Isle of Man ). The Goidelic languages are part of the island Celtic branch of the Celtic languages .

According to Article 8 of the Constitution, Irish is “the main official language” (an phríomhtheanga oifigiúil) of the Republic of Ireland “since [it] is the national language”. The European Union has had Irish as one of its 24 official languages since January 1, 2007 .

The language identifier for Irish is gaor gle(according to ISO 639 ); pglrefers to the archaic Irish of the Ogham inscriptions, sgathe subsequent Old Irish (up to about 900) and mga Middle Irish (900–1200).

history

The beginnings of the Irish language are largely in the dark. Irish is undisputedly a Celtic language , but the way and time by which and when it came to Ireland are hotly debated. It is only certain that Irish was spoken in Ireland at the time of the Ogam inscriptions (from the 4th century at the latest ). This earliest language level is known as archaic Irish . The linguistic processes that had a formative effect on Old Irish , i.e. apocope , syncope and palatalization , developed during this time.

It is generally assumed that (Celtic) Irish gradually replaced the language previously spoken in Ireland (of which no direct traces have been preserved, but which can be demonstrated as a substrate in Irish ) and that it was used until the adoption of Christianity in the 4th and 5th centuries Century was the only language on the island. Contacts to Romanized Britain can be proven. A number of Latin loanwords in Irish date from this period, most of which can be traced back to the regional pronunciation of Latin in Britain.

More words came to Ireland with the returning peregrini at the time of Old Irish (600–900) . These were Irish and Scottish monks who mostly proselytized and practiced monastic scholarship on the continent. This scholarship corresponds to the high degree of standardization and lack of dialect of the very inflexible Old Irish, at least in its written form.

Since the Viking invasions at the end of the 8th century, Irish had to share the island with other languages, but initially only to a small extent. The Scandinavians mainly settled in the coastal towns as traders and gradually assimilated into Irish culture. The Scandinavian loanwords come mainly from the areas of seafaring and trade, for example Middle Irish cnar "merchant ship" <Old Norse knørr ; Central Irish mangaire "traveling dealer" <Old Norse mangari . During this time the language changed from the complicated and largely standardized Old Irish to the grammatically simpler and much more diversified Middle Irish (900–1200). This was reflected, among other things, in the strong simplification of the inflected forms (especially in verbs ), the loss of the neuter and the neutralization of unstressed short vowels.

From today's perspective, the Norman incursion from 1169 onwards was more decisive for Irish. It is no coincidence that people speak of Early Modern Irish or Classical Irish from around 1200 (up to around 1600). Despite the unrest at the beginning of the period and the continued presence of the Normans in the country, this period is marked by linguistic stability and literary wealth. Above all, the peripheral areas in the west and north were mostly subject to tribute, but politically and above all culturally largely independent. The Irish remained thus for the time being by far the most common language, only for administrative purposes was to the 14th century French used the English of the new settlers could only Dublin ( "The Pale ") and Wexford prevail. The Kilkenny Bylaws (1366), which forbade English-born settlers to use Irish, were largely ineffective. The mere fact that they had to be introduced is indicative of the language situation at that time: many of the originally Norman or English families took over the cultural customs of the country in part or in full. By the end of the 15th century, the cities outside the Pales were also Gaelicized again, and in the course of the 16th century Irish invaded the Pale as well.

The planned settlement of English and Scottish farmers in parts of Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries did not change the situation significantly. The lower classes mostly spoke Irish, the upper classes English or Irish. At that time, however, the percentage of Irish speakers in the total population likely began to decline. When the remnants of the old Irish nobility fled the island in 1607 as a result of political unrest ( flight of the counts ), the language was completely removed from its roots in the upper classes. In terms of linguistic history, this is where New Irish or modern Irish begins.

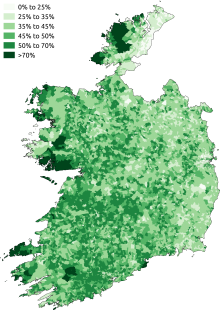

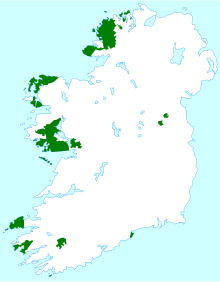

The most decisive factor in the decline of the language in the 19th century was hunger in the countryside. This was widespread and occasionally catastrophic, especially long and intense during the Great Famine of 1845–1849. Between 1843 and 1851 the number of Irish speakers decreased by 1.5 million, the majority of whom starved to death and the rest emigrated. This represents a loss of more than a third, as the total number of Irish speakers is estimated at 3.5 million at the end of the 18th century. Anyone who wanted to achieve something, or in some cases even to survive, had to move to the cities or abroad (Great Britain, USA, Canada, Australia) - and speak English. As parents often had to prepare their children for life in the city or abroad, this development gradually affected the rural areas. Irish became, at least in the public consciousness, the language of the poor, peasants, fishermen and tramps. The language has now been increasingly replaced by English . Resuscitation measures from the late 19th century and above all from the independence of Ireland in 1922 (for example with the participation of Conradh na Gaeilge ) as well as the conscious promotion of the social status of Irish could not stop the development, let alone reverse it. The negative factors affecting the language situation in the late 20th and 21st centuries primarily include the increasing mobility of people, the role of the mass media and, in some cases, a lack of close social networks (almost all Irish speakers live in close contact with English speakers). Today Irish is spoken daily only in small parts of Ireland, and occasionally in the cities. These linguistic islands, which are mostly scattered over the north-west, west and south coasts of the island, are collectively called Gaeltacht (also individually so; plural Gaeltachtaí ).

The 2006 Irish census found 1.66 million people (40.8% of the population) claiming to be able to speak Irish. Of these, at most 70,000 people are native speakers, but not all of them speak Irish every day and in all situations. According to the 2006 census, 53,471 Irish say they speak Irish outside of education every day. In the 2016 census, 1,761,420 Irish reported speaking Irish, which is 39.8% of the country's population. Despite an increasing absolute number of speakers, the percentage in the population fell slightly. 73,803 said they speak Irish every day, of which 20,586 (27.9%) live in the Gaeltachtaí.

In the cities, the number of speakers is increasing, albeit at a still low level. The Irish spoken in the cities, especially by children of second language speakers, often differs from the “traditional” Irish of the Gaeltachtaí and is characterized by simplifications in grammar and pronunciation, which impairs mutual understanding. For example, the distinction between hard and soft consonants, which is necessary for the formation of the plural, is neglected, the plural is accordingly expressed in other ways. The grammar and sentence structure is simplified and partially adapted to English. The extent to which this urban irish adapts to the standard language or develops as an independent dialect or Creole language is a matter of discussion in the research.

Irish is also cultivated among some descendants of the Irish who emigrated to the United States and other countries. Mainly due to a lack of opportunities, however, only a few of them achieve sufficient knowledge to be able to use the language beyond a few nostalgically cultivated idioms. Much of this learning is done through websites and taking Irish courses in Ireland.

Irish in the public, media and education system

Irish can be found in written form throughout Ireland. Official signs, such as place and street signs, are in the entire Republic of Ireland , including some in Northern Ireland, not only in English, but also in Irish. In parts of the Gaeltacht (for example in areas of West Connemara ), guides of this type are only given in Irish. The same goes for memorial plaques and official documents. Legal texts must be published in an Irish language version, the wording of which is binding in cases of doubt. Some government and public institutions have only Irish-language names or those that are often used in addition to the English form:

- Country name: Éire (next to Ireland , often meant poetically or lovingly)

- Parliament: An tOireachtas ("the assembly"), officially only used in Irish

- House of Lords: Seanad Éireann ("Senate of Ireland"), officially only used in Irish

- House of Commons: Dáil Éireann ("Gathering of Ireland"), officially only used in Irish

- Prime Minister: To Taoiseach ("The First", "The Leader"), only Irish in domestic Irish usage

- Vice Prime Minister: An Tánaiste ("The Second"), only Irish in domestic Irish usage

- Member of Parliament: Teachta Dála ("Member of the Assembly"), used almost exclusively in Irish (title TD added to name)

- all ministries: Roinn + respective area of responsibility in the genitive ("Department of / des ..."), mostly used in English

- Post: To Post (“Die Post”), officially only used in Irish

- Bus companies: Bus Éireann ("Bus Ireland"), Bus Átha Cliath ("Bus Dublins"), only Irish used

- Railway company: Iarnród Éireann ("Railway of Ireland"), only used in Irish

- Radio and television station: Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ, "Radio Television Ireland"), only used in Irish

- Telecom: formerly Telecom Éireann ("Telecom Irlands"), officially only used in Irish, meanwhile privatized, now called "Eircom"

- Development promotion company for the Gaeltacht: Údarás na Gaeltachta ("Authority of the Gaeltacht"), only used in Irish

- Police: Garda Síochána ("Guardian of Peace"), is also used in English as the short form "Garda"

Most notices and explanations published for private purposes, for example restaurant menus, are usually only marked in English. However, some private companies also mark part of their public texts in two languages. The individual departments in bookstores and supermarkets are often referred to in Irish, but products of Irish origin are very rare. Ultimately, numerous pubs, restaurants and shops have Irish names.

Several radio stations ( Raidió na Gaeltachta (state), Raidió na Life (private, Dublin)), a television station ( TG4 , initially TnaG , Teilifís na Gaeilge ) with headquarters in Baile na hAbhann , as well as some periodicals , including the weekly, produce in Irish language Foinse ("source") and some mostly culturally or literarily oriented magazines. The youth magazine Nós has also been published since the end of 2008 . Compared to the number of speakers, there is quite a lively Irish-language literature . There are various literary festivals and literary prizes . Irish language books can be found in most bookstores.

Irish is a compulsory subject in all state schools in the country, while the remainder of classes are usually in English. However, there are a number of schools called Gaelscoileanna where Irish is the language of instruction for all subjects. Otherwise, students have had to learn Irish for decades, but seldom have to seriously prove their knowledge. A Leaving Certificate in Irish is required only for access to certain jobs in the civil service and to the colleges of the National University .

Dialects

As a mother tongue or first language , Irish only exists in the form of dialects ; there is no standard language spoken as a mother tongue . However, is of Irish learners mostly the on state initiative, developed and taught standard Irish ( An Caighdeán Oifigiúil , officially valid since 1948) talked, often mixed with a programmed dialect. A distinction is made between the main dialects of Munster , Connacht and Ulster , which can be divided into numerous sub-dialects, mostly geographically separated from one another.

Apart from the areas mentioned above, there have been two tiny language islands in County Meath northwest of Dublin (Rath Cairne and Baile Ghib) since the 1950s , which were mainly used for experimental purposes: Can Gaeltachtaí stay close to a city like Dublin? For this purpose Irish speakers from Connemara were settled and financially supported. By the middle of the 20th century there were other areas with larger numbers of Irish speakers, including parts of Northern Ireland ( Glens of Antrim , West Belfast , South Armagh and Derry ) and County Clare .

The individual dialects differ linguistically in many ways:

-

Lexicons

- “When?”: Munster cathain? , cén uair? , Connemara cén uair? , Donegal cá huair?

-

syntax

- "She is a poor woman":

- Standard Is bean bhocht í (woman is poor she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman is poor in-her)

- Munster Is bean bhocht í (woman is poor she), Bean bhocht is ea í (woman poor is she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman poor is in-her)

- Connacht and Donegal Is bean bhocht í (woman is poor she), Bean bhocht atá inti (woman is poor in-her)

- "She is a poor woman":

- morphology

-

Phonology and Phonetics

- In Munster, 2nd or 3rd syllables are stressed that contain long vowels or -ach-

- Implementation of the " tense " consonants / L / and / N / inherited from Old Irish and their palatalized equivalents / L´ / and / N´ /, example ceann , "head":

- Donegal and Mayo / k′aN / (short vowel, tense N)

- Connemara / k′a: N / (long vowel, tense N)

- West Cork (Munster) / k′aun / (diphthong, untensioned n)

Writing and writing

The Irish will be with Latin letters written (Cló Rómhánach) . In the past, an uncial derived from Latin capital letters was used (Cló Gaelach) . Irish language books and other documents were often printed in this older typesetting until the mid-20th century. Today it is only used for decorative purposes. More under Irish writing .

The so-called Ogham script is much older . It was used from around the 3rd to 6th centuries AD, but absolute dating is not possible. Ogam is an alphabet in which the letters were designated by groups of one to five notches ( consonants ) or periods ( vowels ). The Ogam script is almost exclusively preserved on stone edges, but it is likely that wood was also used.

In Irish, five short vowels (a, e, i, o, u) and five long vowels (á, é, í, ó, ú) are written. Furthermore, 13 consonants (b, c, d, f, g, h, l, m, n, p, r, s, t) are used; the remaining in the Latin alphabet occurring consonants (j, k, q, v, w, x, y, z) only occur in foreign and loan words (about in JIP "jeep"; jab "job"; x-ghathú "X (recording) ", from English x-ray ).

The letter h plays a special role ; it only occurs independently in foreign or loan words (for example in hata "hat"). It also serves as a suggestion before vowels in certain syntactic environments, such as álainn ( adjective "beautiful") vs. go h álainn ( adverb "beautiful"). In addition, the so-called lenition in the typeface is indicated by a trailing h . In the Cló Gaelach , these lenient consonants were marked by a point above them.

pronunciation

The pronunciation of Irish is mainly characterized by two features, the palatalization of consonants and the neutralization of unstressed short vowels .

The pronunciation of a letter or a group of letters always depends on the neighboring letters. Only the length of a character ( síneadh fada or short fada marked long vowels) are always pronounced as they are written. All consonants (with the exception of the “h” in most dialects) are available as variants that can be distinguished phonemically : as palatal and non-palatal consonants. These are easy to recognize in the typeface: On both sides of palatalized consonants (groups) there are only the front vowels e or i , with non-palatal consonants (groups) the back vowels a , o or u . Since there must be either front or back vowels on both sides of the group, the typeface has numerous letters that only serve to identify the pronunciation of other letters. There are few exceptions that need to be learned to pronounce.

Short vowels are reduced to the neutral "murmur" Schwa / ə / in the unstressed position. In Munster, however, the low vowel a retains its quality in the unstressed position if the following syllable contains one of the high vowels í ú , for example cailín [kaˈl′iːn ′] "girl", eascú [asˈkuː] "eel". In Ulster, unstressed a before ch is not reduced, for example eallach / ˈaɫ̪ax / "Vieh".

Initial mutations

Language is influenced by two classes of initial mutations , lenition and nasalization. Historically they were originally ( before the Old Irish ) purely phonological phenomena that grammatically relevant meaning accepted only with the loss of endings in archaic Irish (before about 600 n. Chr.). Today they are used to mark such different grammatical functions as possession ( possessive pronouns ), differentiation between the past tense and imperative , marking of prepositional objects , marking of grammatical gender , marking of direct and indirect subordinate clauses, etc. In each case the pronunciation is changed. Among other things, the lenation turns plosives (/ p /, / g /) into fricatives (/ f /, / ɣ /) with the same point of articulation. In orthography , an h after the consonant concerned is used to identify the lenition. Some examples:

| Pronunciation (not pal.) | Pronunciation (pal.) | |

|---|---|---|

| m | m | m ′ |

| mh | w | v ′ |

| G | G | G' |

| gh | ɣ | ɣ ′ - alternatively "j" (without friction) |

| f | f | f ′ |

| fh | - | - |

In the middle of the word and sometimes at the end of the word, however, lenited consonants often merge with the surrounding vowels to form long vowels or diphthongs .

The consonant groups mb , gc , nd , bhf , ng , bp and dt indicate nasalization. Among other things, voiceless plosives (/ t /) become voiced plosives (/ d /) and voiced plosives (/ d /) become voiced nasals (/ n /). Only the first letter is spoken in these groups. Examples:

| Pronunciation (not pal.) | Pronunciation (pal.) | |

|---|---|---|

| bp | b | b ′ |

| German | d | d ′ |

| mb | m | m ′ |

| bhf | w | v ′ |

| ng | ŋ | ŋ ′ |

grammar

Irish is an island Celtic language and therefore shares many features with other Indo-European languages, especially with regard to the general sentence structure, the existing parts of speech, the noun and verbal categories, etc. but has nothing in common with most other Indo-European languages, including the initial position of the verb, the presence of initial mutations, so-called "conjugated prepositions" and remnants of a double verbal inflection.

Nouns, articles and adjectives

Modern Irish inherited a great wealth of inflection from Old Irish, which today, however, is largely limited to the verb. The noun and the adjective basically only have two to three cases ( nominative / accusative , vocative and genitive ). In fixed idioms there are traces of the dative , which is otherwise only actively used in some dialects. There are two numbers , singular and plural, but a dual was still recognizable in Old Irish. In addition, nouns are divided into genera , feminine and masculine, the neutral gender has disappeared in Central Irish. The product is for both genders at ( plural : na ). In most cases, however, a distinction is maintained, since the initials of masculine and feminine nouns usually behave differently after the article.

Verbs

The verb, on the other hand, has a wide range of inflection options even today. Verbs are conjugated according to the categories mode , tense , aspect and person . There is no “classic” gender verb in the sense of active and passive, but there are corresponding substitutes. The indicative, the imperative and, increasingly, the subjunctive are used as modes. A distinction is also made between five tenses: present tense , past tense (simple past), imperfect tense (repeated / continuous past), future tense and conditional . Tenses such as perfect and past perfect can be formed by other constructions, some of which work through a combination of lexical means and a displacement of agent and patient. The "tense" conditional has a strongly modal aspect, but is formed within the paradigms of the tenses and is therefore included in them.

Irish has a habitual and a progressive aspect. The habitual aspect is primarily used for statements that are generally valid or not precisely specified in terms of time, the progressive aspect for statements in which the action occurs during speaking time. With the habitual Ólaim tae (“I drink tea”) the speaker says that he generally likes tea, with the corresponding progressive Tá mé ag ól tae (also “I drink tea”) that he is just about to add tea drink.

Furthermore, Irish has three grammatical persons in the singular and in the plural. In the case of the pronouns that accompany the verb forms, a distinction is made between masculine and feminine in the singular analogous to the nouns (sé / sí) , in the plural not (siad) . There is also an impersonal verb form (also called "autonomous verb form") that does not designate a specific person. This form is comparable to the German indefinite “man” : léitear leabhar, “one reads a book”, “someone reads a book”, from léigh, “to read”. Often it can also be translated as passive: “a book is read”. This verbal system is supplemented by participles and the frequently used verbal noun (comparable to German substantivated verbs), which is also used instead of an otherwise missing infinitive .

In the course of the development of Irish, its originally synthetic structure was increasingly replaced by analytical formations . This development can be seen particularly well with the verb, as there is a situation today in which analytical and synthetic forms are used “mixed up” within a flexion paradigm. The following tables show this for the standard language, but the use of certain analytical or synthetic forms for the individual persons and tenses is very different in the dialects. In general, synthetic forms are used in the south and more analytical forms in the north.

Class 1 verb (monosyllabic stem) with a palatal final: bris , "break"

| Present | Future tense | preterite | Past tense | Conditional | Conj. Pres. | Conj. Prät. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | brisim | brisfead, brisfidh mé | bhriseas, bhris mé | bhrisinn | bhrisfinn | brisead, brise mé | brisense |

| 2nd Sg. | brisir, briseann tú | brisfir, brisfidh tú | bhrisis, bhris tú | bhristeá | bhrisfeá | brisir, brise tú | bristeá |

| 3rd Sg. | briseann sé / sí | brisfidh sé / sí | bhris sé / sí | bhriseadh sé / sí | bhrisfeadh sé / sí | brisidh / brise sé / sí | briseadh sé / sí |

| 1st pl. | brisimid, brisean muid | brisfeam, brisfimid, brisfidh muid | bhriseamar, bhris muid | bhrisimis | bhrisfimis | briseam, brisimid | brisimis |

| 2nd pl. | briseann sibh | brisfidh sibh | bhris sibh | bhriseadh sibh | bhrisfeadh sibh | brisish / brise sibh | briseadh sibh |

| 3rd pl. | brisid, briseann siad | brisfid, brisfidh siad | bhriseadar, bhris siad | bhrisidís | bhrisfidís | brisid, breeze siad | brisidís |

| impersonal | bristear | brisfear | briseadh | bhristí | bhrisfí | bristear | bristí |

Verb of class 2 (polysyllabic stem) with a non-palatal final: ceannaigh , "buy"

| Present | Future tense | preterite | Past tense | Conditional | Conj. Pres. | Conj. Prät. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | ceannaím | ceannód, ceannóidh mé | cheannaíos, cheannaigh mé | cheannaínn | cheannóinn | ceannaíod, ceannaí mé | ceannaínn |

| 2nd Sg. | ceannaír, ceannaíonn tú | ceannóir, ceannóidh tú | cheannaís, cheannaigh tú | cheannaíteá | cheannófá | ceannaír, ceannaí tú | ceannaíteá |

| 3.Sg. | ceannaíonn sé / sí | ceannóidh sé / sí | cheannaigh sé / sí | cheannaíodh sé / sí | cheannódh sé / sí | ceannaí sé / sí | ceannaíodh sé / sí |

| 1st pl. | ceannaímid, ceannaíonn muid | ceannóimid, ceannóidh muid | cheannaíomar | cheannaímis | cheannóimis | ceannaímid | ceannaímis |

| 2nd pl. | ceannaíonn sibh | ceannóidh sibh | cheannaigh sibh | cheannaíodh sibh | cheannódh sibh | ceannaí sibh | ceannaíodh sibh |

| 3rd pl. | ceannaíd, ceannaíonn siad | ceannóid, ceannóidh siad | cheannaíodar, cheannaigh siad | cheannaídís | cheannóidís | ceannaíd, ceannaí siad | ceannaídís |

| impersonal | ceannaítear | ceannófar | ceannaíodh | cheannaítí | cheannóifí | ceannaítear | ceannaítí |

Negations are formed with the particle ní (in the past tense mostly níor ), questions with the particle an (or ar ). Some verbs have suppletive stems , sometimes even with positive / negative forms: chuaigh tú "you went", but ní dheachaigh tú "you did not go".

prepositions

Prepositions are used in Irish in two forms, simple and compound prepositions. The conjugated prepositions, which are a special form of simple prepositions, are striking. These merge with a personal pronoun to form a new word, which in most cases, however, contains phonetic features of the original words. The meaning of the conjugated preposition changes accordingly: ar ("on") to "on me", "on you", "on him" or "on", "on her" etc.

| ag (at, at, at) | ar (on, on, to, to, to) | le (with, from) | faoi (under, from) | do (to, for) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | agam | orm | liom | fúm | dom, domh |

| 2nd Sg. | agat | place | leat | fút | duit |

| 3. Sg. Mask. | aige | air | quiet | faoi | do, do |

| 3rd Sg. Fem. | aici | uirthi | leithi (léi) | fithi | di |

| 1st pl. | againn | orainn | linn | fúinn | dúinn |

| 2nd pl. | agaibh | oraibh | libh | fúibh | daoibh, díbh |

| 3rd pl. | acu | orthu | leo | fúthu | dóibh |

Together with nouns, including names, simple prepositions are used as such: ag an doras , "at the door", ag Pádraig , "at Pádraig", as opposed to aige , "at him / this" (the door) or " with him ”(Pádraig). Many simple prepositions lead to the lenition of the following noun ( ar bhord , "on a table", from bord ) and in connection with the article on nasalization ( ar an mbord , "on the table"). Compound prepositions usually consist of a simple preposition and a noun and rule the genitive: in aghaidh na gaoithe , "against the wind", literally "in the face of the wind". Personal pronouns are accordingly infigured, so that basically circumpositions arise: in a haghaidh , "against them" (literally "in their face"; gaoth , "wind" is feminine). Unlike in German (“for the sake of the circumstances”), there are no postal positions.

Numerals

In Irish, in addition to the common categories of cardinal and ordinal numbers, there are also modified systems for counting objects and people. The numbers from 2 to 10 lead to initial mutations.

| Cardinal number |

Ordinal number |

Counting items * |

Counting people * |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a haon | chéad | aon (cheann / lámh / phunt) amháin, (ceann / lámh / punt) amháin | duine, duine amháin |

| 2 | a dó | dara, tarna, ath- | dhá (cheann / láimh / phunt) | hosted |

| 3 | a trí | tríú | trí (cheann ~ cinn / lámha / phunt) | triúr |

| 4th | a ceathair | ceathrú | cheithre / ceithre (cheann ~ cinn / lámha / phunt) | ceathrar |

| 5 | a cúig | cúigiú | cúig (cheann ~ cinn / lámha / phunt) | cúigear |

| 6th | a sé | séú | sé (cheann ~ cinn / lámha / phunt) | seisear |

| 7th | a mind | seachtú | seacht (gceann ~ gcinn / lámha / bpunt) | seachtar, mórsheisear |

| 8th | a hocht | ochtú | ocht (gceann ~ gcinn / lámha / bpunt) | ochtar |

| 9 | a naoi | naoú | naoi (gceann ~ gcinn / lámha / bpunt) | naonúr |

| 10 | a dyke | deichniú, deichiú | dike (gceann ~ gcinn / lámha / bpunt) | deichniúr |

| 11 | a haon déag | aonú (ceann) déag | aon (cheann / lámh / phunt) déag, (ceann / lámh / punt) déag | aon duine déag, duine déag |

| 20th | fiche | fichidiú, fichiú | fiche (ceann / lámh / punt) | fiche duine |

| 21st | a haon is fiche | aonú (ceann) is fiche | aon (cheann / lámh / phunt) is fiche, (ceann / lámh / punt) is fiche | duine is fiche |

| 24 | a ceathair is fiche | ceathrú (ceann) is fiche | cheithre (cheann ~ cinn / lámha / phunt) is fiche | ceathrar is fiche |

| 100 | céad | céadú | céad (ceann / lámh / punt) | céad duine |

* punt means "pound", used here as a typical countable noun, ceann means "head", but can also be used to count indefinite objects. lámh means "hand, arm". Ceann and lámh belong to the nouns that always appear in the plural ( cinn , lámha ) after numbers greater than 2 , and always appear in the "dual" after 2. The given words for counted persons already contain the information “persons”: triúr means “three persons”. More precise terms can be added: triúr peileadóirí , "three footballers"

The numbers 11–19 have the additional component déag , corresponding to the German “-zehn” ( a trí déag = thirteen , trí phunt déag = thirteen pounds ).

For the formation of higher numbers, both a 10 ( seachtó , 60) and a 20 system ( trí fhichid , 3 × 20) are used. However, the 10er system is more common today due to its use in the school system. Counted objects / people are placed between units and tens : dhá bhord is caoga , “52 tables”, literally “two table and fifty”. The number is usually given in the singular.

syntax

The syntax of the neutral sentence requires a relatively fixed sentence structure. However, this can be deviated from significantly in order to nuanced the focus and the meaning of the sentence. As with all island Celtic languages, the neutral sentence order is verb-subject-object . Questions are formed by preceding particles, so that the structure of the sentence remains unchanged:

- Déanann sé to obair. ("He does the work.", Lit. "He does the work.")

- An ndéanann sé an obair? ("Does he do the work?", Lit. " Particle - does he do the work?")

However, all semantically independent parts of the sentence can be moved to the front by means of sentence remodeling in order to change the focus of the sentence. For example, a neutral sentence is:

- Rinne mé an obair leis an athair inné. ("I did the work with the father yesterday.", Literally "I did the work with the father yesterday.")

However, the rate can be changed as follows:

- An obair a rinne mé leis an athair inné. ("The work" in focus)

- Mise a rinne an obair softly an athair inné. ("I" in focus)

- (Is) leis an athair a rinne mé an obair inné. ("With the father" in focus)

- Inné a rinne mé an obair leis an athair. (“Yesterday” in focus).

Direct pronominal objects usually come at the end of a sentence.

- Chonaic mé ar an tsráid é. ("I saw him on the street.", Lit. "I saw him on the street.")

With a noun phrase as an object, however, the normal sentence structure VSO is adhered to:

- Chonaic mé an fear ar an tsráid. ("I saw the man on the street.", Lit. "I saw the man on the street.")

Text samples

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1

Irish in modern orthography

Airteagal 1.

Saolaítear gach duine den chine daonna saor agus comhionann i ndínit agus i gcearta. Tá bua an réasúin agus an choinsiasa acu agus ba cheart dóibh gníomhú i dtreo a chéile i spiorad an bhráithreachais.

Pronunciation (Aran Islands)

/ sˠiːɫiːtʲəɾˠ gˠaːx dˠɪnʲə dʲənʲ çɪnʲə dˠiːnə sˠiːɾˠ əsˠ kˠoːɪnˠənˠ ə nʲiːnʲətʲ əsˠ ə gʲæːɾˠtˠə. tˠɑː bˠuːə ə ɾˠeːsˠuːnʲ əsˠ ə xʌnʲʃəsˠə aːkˠəbˠ əsˠ bˠə çæːɾˠtˠ dˠoːbʲ gʲɾʲiːvuː ə dʲɾʲoː ə çeːlʲə ə sˠpʲɪrˠədˠ ə vˠɾˠɑːrʲəxəʃ. /

Our Father

Transcription of Irish (dialect of Coolea)

Ár n-Athair atá ar neamh go naomhuighthear t'ainm, go dtagaidh do ríoghdhacht, go ndéintear do thoil ar an dtalamh mar a déintear ar neamh.

pronunciation

/ ɑːr nahirʲ əˈtɑː erʲ nʲav gə neːˈviːhər tanʲimʲ, gə dɑgigʲ də riːxt, gə nʲeːnʲtər də holʲ erʲ ə daləv mɑr ə dʲeːnʲtʲər er nʲav. /

German interlinear translation

Our Father who-is in heaven, that be-hallowed your-name, that your kingdom come, that your will be made on earth as what is-made in heaven.

Today's standard Irish

Ár nAthair atá ar neamh go naofar d'ainm, go dtaga do ríocht, go ndéantar do thoil ar an talamh mar a dhéantar ar neamh.

saying

Transcription of Irish (dialect of Coolea and today's standard)

Is maith í comhairle an droch-chomhairligh.

pronunciation

/ is mɑh iː koːrˈlʲiː ən droˈxoːrligʲ. /

German translation

Good is her bad counselor's advice. = Good is the advice of a bad advisor. ( comhairle , "advice", is female)

Both text excerpts are based on field recordings from the 1930s or 1940s from West Cork . The transcriptions were made by Brian Ó Cuív and published in 1947.

literature

- Arne Ambros: Sláinte! Irish textbook for self-teaching. Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-89500-512-6 (with key ISBN 3-89500-544-4 )

- Thomas F. Caldas, Clemens Schleicher: Dictionary Irish-German. Helmut Buske, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-87548-124-0

- Desmond Durkin Master Serious: New Irish Reader. Texts from Cois Fhairrge and the Blasket Islands. Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-89500-602-9

- Franz Nikolaus Finck: The aran dialect. NG Elwert'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Marburg 1899.

- Lars Kabel: Irish Gaelic. Word for word (= gibberish . Volume 90 ). 9th edition. Reise-Know-How-Verlag Rump, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-89416-797-4 .

- T. F. O'Rahilly: Irish Dialects Past and Present . Browne & Nolan, 1932; Reprinted, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1972. ISBN 0-901282-55-3

- Mícheál Ó Siadhail: Modern Irish: Grammatical structure and dialectal variation. Cambridge University Press 1989, ISBN 0-521-37147-3 .

- Mícheál Ó Siadhail: Textbook of the Irish language. Helmut Buske, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-87548-348-0 (incl. Pronunciation CD)

- E. C. Quiggin: A Dialect of Donegal: Being the Speech of Meenawannia in the Parish of Glenties . Cambridge University Press, 1906.

- Martin Rockel: Basics of a History of the Irish Language. Austrian Academy of Sciences. Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-7001-1530-X

- Britta Schulze-Thulin, Niamh Leypoldt: Irish for beginners . Buske, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-87548-574-5 .

- Alexey Shibakov: Irish Word Forms / Irish Word Forms (Book I) . epubli, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-7450-6650-0 .

- Alexey Shibakov: Irish Word Forms / Irish Word Forms (Book II) . epubli, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-7450-6652-4 .

Web links

- Eist / Listen live radio streaming on the Internet, click on the top right: "R na G Beo"

- Cúrsa Gaeilge: German-language Irish course development

- Gramadach na Gaeilge German-language online grammar

- Online version of the Irish-English and English-Irish standard dictionaries Ó Dónaill and de Bhaldraithe

- newer English-Irish online dictionary

- German online dictionary and grammar for Irish

- English online dictionary from DCU (Dublin City University) on technical terms

- Conradh na Gaeilge Bheirlín

- Conradh na Gaeilge Hamburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ Constitution of Ireland - Bunreacht na hÉireann (text of the Irish constitution in English; there, however, "first official language", not "main official language") (PDF; 205 kB)

- ^ EG Ravenstein, "On the Celtic Languages of the British Isles: A Statistical Survey," in Journal of the Statistical Society of London , vol. 42, no.3, (September, 1879), p. 584

- ↑ u. a. Davies, Norman: The Isles. A History , Oxford University Press 1999. ISBN 0-19-514831-2

- ↑ Rockel 1989, pp. 49-50

- ↑ Rockel 1989, pp. 56-57

- ↑ Rockel 1989, pp. 64-70

- ↑ Rockel 1989, p. 82

- ↑ Máirtín Ó Murchú, “Aspects of the societal status of Modern Irish”, in The Celtic Languages , London: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0-415-01035-7

- ↑ Central Statistics Office Ireland: Census 2006 - Volume 9 - Irish Language ( Memento of November 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ Census 2016 Summary Results - Part 1 - CSO - Central Statistics Office ( en )

- ^ Brian Ó Broin: Schism fears for Gaeilgeoirí . In: The Irish Times , January 16, 2010.

- ^ O'Rahilly 1932, passim

- ↑ Ó Siadhail 1989, p. 318

- ↑ Ó Siadhail 1989, pp. 165-66

- ↑ Ó Siadhail 1989, p. 39

- ↑ Quiggin 1906, p. 9

- ↑ Ailbhe Ó Corráin, "On verbal aspect in Irish with Particular reference to the progressive". Miscellanea Celtica in Memoriam Heinrich Wagner, Uppsala 1997

- ^ O'Rahilly 1932, p. 219

- ^ Brian Ó Cuív. The Irish of West Muskerry: A Phonetic Study . Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1947. ISBN 0-901282-52-9