Balkan Wars

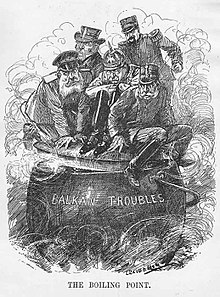

The Balkan Wars were two wars between the states of the Balkan Peninsula in 1912 and 1913 in the run-up to the First World War . As a result, the Ottoman Empire in Europe was pushed into the current borders of Turkey and had to cede large areas to neighboring countries.

First Balkan War

Initial situation and Balkan Federation 1912

Russia met its diplomatic defeat after the annexation of Bosnia by Austria-Hungary in 1908 with the creation of the Balkan alliance between Serbia and Bulgaria under Russian patronage . The alliance of the two Balkan countries expanded with the annexation of Greece and Montenegro , which changed the security policy goals of the alliance. The primary goal was not Austria-Hungary, but the Ottoman Empire . The allies Serbia and Bulgaria agreed to accept an arbitration ruling by the Russian tsar regarding the annexation of newly won territories. Greece, on the other hand - with the political support of Great Britain and France - rejected Russian suzerainty and wanted to regulate the incorporation of possible newly won territories through an international conference.

Out of uncertainty about the support of its allies France and Great Britain in the Balkans inquiry, Russia agreed to a diplomatic note issued on behalf of all the great powers in early October, which insisted on the territorial status quo in the Balkans. "However, the Balkan states disregarded this declaration, which is unrealistic in the current situation, with some right."

At the beginning of the war the Bulgarian armed forces were around 233,000 strong, the Serbian around 130,000, the Montenegrin 31,000 and the Greek around 80,000. At the beginning of the war that totaled 474,000 soldiers. More soldiers were drafted during the wars: Serbia ultimately held 350,000 to 400,000 men under arms, Bulgaria 600,000 and Greece 300,000. Greece was the only Balkan state to have a notable navy . The Ottoman troops on the Balkan Peninsula comprised around 290,000 men. The Ottoman Empire sent reinforcements from Asia only after the decisive fighting had ended. The reasons for this were that the Sublime Porte feared a Russian invasion over the Caucasus , but above all that the empire was still at war with Italy . In addition, the Ottoman troops were less well equipped than the soldiers of the Balkan League and had an outdated communication structure (dating from the first half of the 19th century). The obstruction of supplies by the Greek and Bulgarian navies also played a not insignificant role.

Course of war

Montenegro declared the Ottoman Empire on September 25th . / October 8, 1912 greg. and on October 16 the Ottoman Empire launched war on Bulgaria. The next day, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece jointly declared war on the Ottoman Empire.

The following military defeats of the Ottoman Empire, which had been weakened by the 1912 Italo-Turkish War and various uprisings in the Balkan provinces, proved that it could no longer maintain its European rule.

On October 21, 1912, the Ottoman forces were defeated by the Greek army near the Sarantaporos River and on October 24, the Greek forces marched into Kozani . On October 31, the Ottoman troops at Giannitsa were defeated again and the next day the city was taken by the Greek troops. The Greek army then marched towards Monastir (today's Bitola ), but changed their thrust and reached Saloniki on November 7th, a few hours before the invasion of the Bulgarian armed forces. The Turkish high command in the city with around 26,000 soldiers capitulated to the Greek army and was allowed to withdraw unmolested. At this point in time, the first disputes between the Greek and the Bulgarian associations advancing in Salonika were already emerging. On February 21, 1913, Ioannina was captured by the Greek army after a battle of Bizani lasting several days. About 33,000 Turkish soldiers were taken prisoner. The Greek troops reached the port of Valona (today's Vlora ) on the Adriatic Sea on March 6th . The Greek navy forced the Ottoman fleet to seek protection in the Dardanelles , thereby cutting off the logistical support of the Ottoman army from Asia Minor .

The Serbian armed forces defeated the Ottoman army on November 3rd and 4th, 1912 in Kumanovo . On November 6th, they moved into Üsküb (today's Skopje ). They took the Prilep region in mid-November and Monastir on November 29. Then they supported the Montenegrin associations in the region around Novi Pazar and on May 3, 1913 they conquered the city of Shkodra after a siege of several months . About 20,000 Ottoman soldiers left the embattled region and sought to join the Ottoman units fighting against the Greek troops in Epirus .

The Bulgarian army defeated the Ottoman troops in the Battle of Kirk Kilisse (October 21/22, 1912) and again at the end of October in the Battle of Lüleburgaz . Over 20,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or captured on either side in the battle. The successes of the Bulgarians even led Russia to consider whether to come to the aid of the Ottoman Empire. Troop landings on the Bosporus were supposed to prevent Bulgarian control of the straits. Between November 4th and 8th, the Bulgarians tried to take Constantinople without success . Bulgaria then concluded a separate armistice with the Ottoman government on November 20, 1912 ( High Porte ). On February 2, 1913, however, the Bulgarian associations began again with military operations after a coup d'état by the Young Turks under Ismail Enver in Constantinople. Adrianople (today's Edirne ) fell into the hands of the Bulgarian units after a siege on March 26, 1913, after two Serbian divisions had come to their aid. A total of around 65,000 Ottoman soldiers went into Bulgarian captivity. The Battle of Vasopetra on April 27, 1913 claimed the lives of American soldiers of Greek descent . On May 1, 1913, the Ottomans reached another armistice.

As a result of the events, the Principality of Albania had already declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire on November 28, 1912. The proclamation was held in no time, as the Montenegrins, Serbs and Greeks who moved into the Albanian settlement area had conquered large areas. At the time of the declaration of independence, Albania only had any significant state power between the cities of Korça , Tepelena and Vlora .

Results

With the mediation of the major European powers , peace negotiations began in London in December 1912. With the signing of the London Treaty , the war ended on May 30, 1913.

The Ottomans renounced all European areas west of the line between Midia on the Black Sea and Enez on the Aegean coast , their centuries-long rule on the Balkan Peninsula thus came to an end within a few months. As a result there was a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Muslims to Asia Minor. The victorious states forbade Muslim clothing in the areas they had conquered , mosques were abandoned to decay or converted into churches or converted back.

Albania's independence was recognized. With Italian and German support, Austria-Hungary was able to ensure that the newly formed state was also awarded areas that had been occupied by the states of the Balkan Federation during the war. The definition of the Albanian border finally envisaged a territory that comprised almost half of the Albanian settlement area. This was a defeat for Serbia and Greece, who had previously agreed on a division of the Albanian territories. With the creation of Albania, Viennese diplomacy achieved its goal of keeping Serbia away from the Adriatic . On the question of Serbia's access to the Adriatic at Skutari , Russian and Austrian Balkan policies collided directly; there was a serious international crisis.

Thrace was to fall to Bulgaria, and Macedonia was to be divided between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria.

The Cretan state officially united with Greece.

Second Balkan War

Balkan Federation 1913

After the agreed ceasefire with the Ottomans, a dispute arose a little later about the distribution of the territories. The Bulgarian leadership was not satisfied with the demarcation of the border in Macedonia, which contradicted the pre-war agreements, and demanded that Serbia cede this occupied territory. In addition, the Bulgarian government overestimated the strength of its own army and misunderstood the strategic situation in the Balkans, which manifested itself with the defense alliance of May 19, 1913 between Belgrade and Athens . The Serbs were dissatisfied that Albania was blocking their desired access to the Adriatic. Romania , which had remained neutral in the First Balkan War, acted independently against Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War. The Ottoman Empire finally seized the opportunity to reclaim territories lost during the war between the Serb, Greek and Bulgarian forces.

Acts of war

On the night of June 29, 1913, Bulgarian troops attacked the Greek and Serbian armies simultaneously without Bulgaria officially declaring war on the two states. The fighting between Serres and Saloniki ended with a victory for the prepared defenders. Serbia and Greece declared war on Bulgaria on July 8, 1913. Romania's declaration of war followed on July 10, and the Ottoman Empire on July 11. Bulgaria was attacked from all sides. At the time, the bulk of his armed forces were involved in fierce fighting with Greek units. The Romanian troops therefore reached the suburbs of Sofia within a few days without significant resistance , while the Ottoman troops marched into the undefended Adrianople on July 21. Bulgaria, which was far inferior to this coalition of forces, had to surrender within a few weeks. In the last days of the war, clashes between allied Greek and Serbian associations in the Kozani region became apparent.

Results

After the armistice, Bulgaria had to cede almost all the conquests achieved in the First Balkan War in the Bucharest Peace Treaty of August 10, 1913.

Most of the Macedonia region fell to Greece ( Aegean Macedonia ) and Serbia ( Vardar Macedonia , today's North Macedonia ), the south of Dobruja went to Romania and Eastern Thrace with Adrianople back to the Ottoman Empire. Romania's entry into the war against Bulgaria “poisoned” relations between the two countries for years. Even today you can feel an animosity in the behavior of both countries towards one another. However, such hostilities exist between many Balkan peoples, triggered primarily by the many war crimes. Bulgaria initially retained only a small part of the eastern region of Macedonia. With Russia intervening in the negotiations, Bulgaria finally got access to the Aegean with the Treaty of Constantinople on September 29, 1913 with Western Thrace. This caused a new conflict with Greece which claimed the region for itself. At the end of the Second Balkan War, the Ottomans had recaptured Eastern Thrace with Edirne (Adrianople) with the help of the irregulars from " Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa " - an Ottoman secret organization that mostly operated independently of the Sublime Porte but supported by the military - and, as it did later, during the genocide the Armenians expelled or murdered almost the entire Bulgarian minority there .

In Western Thrace, with the support of the "Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa", control was taken back and the Provisional Government of Western Thrace was founded. Due to political fears, the Hohe Pforte did not force the independence movement in the region of Western Thrace, because hundreds of thousands of Muslims and Christian Orthodox also lived in Western, Northern and Eastern Thrace. The Treaty of Constantinople, alongside the Treaty of Bucharest, was the second important treaty at the end of the Second Balkan War. With this, Western Thrace was left to Bulgaria with the consent of the Ottoman Empire (with the Lausanne Treaty of 1923 the region fell to Greece). However, the Treaty of Constantinople did not deal with the refugee problem between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire; this was not regulated until 1925 in the Treaty of Angora .

losses

The wars claimed dead and wounded soldiers: Serbia 71,000, Montenegro 11,200, Bulgaria 156,000, Greece 48,000 and the Ottoman Empire around 100,000. This does not include civilian casualties.

Consequences and evaluation

The Balkan Wars paved the way for the Southeast European states to enter the First World War . The Ottoman Empire, like Bulgaria, isolated in the Balkans, entered the war on the side of the Central Powers . Both powers strove to revise the newly drawn borders.

In contrast to the model of “political wars” that raged in Europe at the time, the Balkan wars were characterized by a high degree of ethnically based violence. All sides murdered and expelled numerous civilians from the other peoples. The Peace of Constantinople of 1913 is considered to be the first peace treaty in history that provided for a planned exchange of population between the contracting parties with the aim of ethnic segregation. In the early summer of 1914, a similar agreement followed between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, which, however, was hardly implemented because of the beginning of the First World War.

The Balkan Wars and the following First World War poisoned relations between the Balkan peoples for decades.

The war deepened the divisions within the Austro-Hungarian Danube Monarchy . Sections of the Slovenian and Croatian intellectual elites and politicians openly showed sympathy for the Serbs. On October 20, the first Croatian-Slovenian parliament met in Ljubljana, which advocated a trialist solution (equal say for all Slavic peoples in the Danube Monarchy, against the Austro-Hungarian dualism ). Like most other European politicians, the Austro-Hungarian Empire predicted a victory for the Ottoman Empire. Austria-Hungary absolutely wanted to prevent the Serbs from accessing the Adriatic and tried to exert political influence on Serbia accordingly. In contrast, Slovenian and Croatian politicians believed that the stability of the monarchy would be best served if the interests of the Slavic peoples who lived outside the Danube monarchy were also taken into account and not fobbed off with lazy compromises.

See also

- The Yugoslav Wars (1991-2001) leading to the breakup of the State of Yugoslavia

literature

- The great politics of the European cabinets 1871–1914 . Volume 36.2: The Liquidation of the Balkan Wars 1913–1914 . Part 2, Berlin 1926. (Source edition).

- Karl Adam: Britain's Balkan Dilemma. British Balkan Policy from the Bosnian Crisis to the Balkan Wars 1908–1913. Kovač, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8300-4741-4 .

- Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small state politics and ethnic self-determination in the Balkans . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 .

- Hans-Joachim Böttcher : Ferdinand von Sachsen-Coburg and Gotha 1861–1948 - A cosmopolitan on the Bulgarian throne . Osteuropazentrum Berlin - Verlag (Anthea Verlagsgruppe), Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-89998-296-1 , pp. 219–268.

- Edward J. Erickson: Defeat in Detail. The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-275-97888-5 .

- Richard C. Hall: Balkan Wars 1912-1913. Prelude to the First World War. Routledge, London 2000, ISBN 0-415-22946-4 .

- Magarditsch A. Hatschikjan: Tradition and Reorientation in Bulgarian Foreign Policy . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-486-55001-2 .

- Gunnar Hering : The political parties in Greece 1821-1936 . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-486-55871-4 .

- Wolfgang Höpken: Archaic violence or harbingers of “total war”? The Balkan Wars 1912/13 in 20th Century European War History. In: Ulf Brunnbauer (Ed.): Interfaces. Society, Nation, Conflict and Memory in Southeastern Europe. Festschrift for Holm Sundhaussen on his 65th birthday . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58346-5 , pp. 245-260.

- Catherine Horel (ed.): Les guerres balkaniques (1912–1913): Conflits, enjeux, mémoires . Peter Lang, Brussels 2014, ISBN 978-2-87574-185-1 .

- Florian Keisinger: Uncivilized Wars in Civilized Europe? The Balkan Wars and Public Opinion in England, Germany and Ireland, 1876–1913. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-76689-2 .

- Peter Mario Kreuter: The Flâneur of Salonica. The First Balkan War in the Private Correspondence of King George I of Greece with Fritz Peter Uldall (1847-1931). In: Thede Kahl, Johannes Kramer, Elton Prifti (eds.): Romanica et Balcanica. Wolfgang Dahmen on his 65th birthday . Munich 2015, pp. 761–778.

- Ioannis Kyrochristos (Ed.): A concise history of the Balkan Wars, 1912-1913. Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Athens 1998, ISBN 960-7897-07-2 .

- Dimitris Michalopoulos: The First Balkan War. What went on behind the scenes. In: Mehmet Ersan, Nuri Karakaş (ed.): Osmanlı Devleti'nin Dağılma Sürecinde Trablusgarp ve Balkan Savaşları, 16-18 Mayıs 2011 / İzmir. Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara 2013, ISBN 978-975-16-2654-7 , pp. 183–191.

- Leon Trotsky : The Balkan Wars 1912–1913 . Arbeiterpresse Verlag, Essen 1996, ISBN 3-88634-058-9 .

Web links

- Thematic portal Balkan Wars 1912–1913 on osmikon, the research portal on Eastern, Central Eastern and Southeastern Europe

- A Balkan Tale

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wolfgang J. Mommsen: The Age of Imperialism (= Fischer world history. Volume 28). Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-60028-6 , p. 256.

- ↑ a b c Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , pp. 35, 72 and 121.

- ↑ a b Andrej Rahten: Sto let po izbruhu balkanskih vonj-Kraljev sin sproži prvi topovski strel, godba zaigra himno. ( One hundred years after the outbreak of the Balkan Wars - The King's son releases the first cannon shot, the brass band plays the hymn. ) Saturday supplement (Sobotna priloga) of the Slovenian newspaper Delo , Ljubljana, October 6, 2012, p. 16 (Andrej Rahten, then Research Associate at the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts , Ambassador in Vienna ( Memento from March 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ All dates according to the Gregorian calendar . For the conversion to the Julian calendar , which is often used in the literature on this subject, see Conversion between the Julian date and the Gregorian calendar .

- ↑ Wolfgang J. Mommsen: The Age of Imperialism (= Fischer world history. Volume 28). Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-60028-6 , p. 257.

- ^ Dörte Löding: Germany and Austria-Hungary's Balkan Policy from 1912 to 1914 with special consideration of their economic interests. Hamburg 1969, pp. 38 and 157.

- ↑ Wolfgang J. Mommsen : The Age of Imperialism (= Fischer world history. Volume 28). Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-60028-6 , p. 258.

- ↑ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , p. 58.

- ^ Hilke Gerdes: Romania. More than Dracula and Wallachia. Bonn, 2007, ISBN 978-3-89331-871-1 , p. 36.

- ↑ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , pp. 78-82.

- ↑ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War. Small State Policy and Ethnic Self-Determination in the Balkans. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 , p. 72.