Buddhism in Central Asia

In its heyday, in the first Christian millennium, Buddhism in Central Asia had an important mediation between the Indian states and the development in China , especially after the fall of the later Han dynasty (220). The mutual cultural exchange was most intense from the sixth century onwards. Since the Islamic campaigns of conquest, Buddhism has been practically meaningless in the region.

"Central Asia" refers to the various states or empires that existed in the Tarim Basin and neighboring areas such as Badachschan and the Oxus region - mostly around the oases along the Silk Road - essentially the area within 36–43 ° North and 73– 92 ° East. The impulses that led to the conversion of the Tibetans, Mongols , Kalmyks and Buryats also emanated from Central Asia . This is the area referred to in Chinese literature as "the western regions".

development

Occasionally theories have been put forward that the region was already v. Was completely evangelized by Graeco Buddhism . It could be assumed that not only King Menandros , as came over in the "Questions of Milindapañha ", but that his empire had also converted to Buddhism. The reliability of a passage in the Mahāvaṃsa (Chronicle of Sri Lanka ) that the "wise Mahādeva" visited the island with a large number of monks from the region in 101-77 BC also remains unclear.

Parts of the Parthian Empire could have been possible since the 1st century BC. Have been Buddhist. The Parthian prince An Shih-kao ( 安世高 ), who arrived in China in 148 , became one of the most important early missionaries in China.

Western region

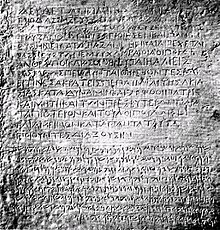

The earliest archaeologically verifiable Buddhist presence dates from the time of Ashoka , of which stone inscriptions in Aramaic and Greek have been found in Kandahar and Laghman .

On the coins of some Indo-Greek kings there are inscriptions and images that have been interpreted Buddhistically. The eight-spoke wheel, a symbol of Buddhism, appears on some of Menandros' coins . On the coins of Straton I (approx. 125 to approx. 110 BC) and other kings, such as B. Peukolaos can be found e.g. B. the term Dharmika (the Dharma ), which was used Buddhist, but also Hindu.

One stands on somewhat safer ground with the Indo-Scythians . Together with coins from King Azes II (approx. 35–12 BC), the bimaran relic was found , on which one of the oldest depictions of the Buddha is located.

The founder of the Kushana dynasty Kujula Kadphises , from the Scythian tribe of the Yuezhi ( Yueh-chi ), conquered most of today's Afghanistan and established his suzerainty over the entire Indus valley. In the first century his grandson Kanischka (ruled after 78 or 100-125) extended the sphere of influence to the north Indian empire Gandhara , with its capital in Purushpura (today: Peschawar ), where at that time a great temple complex ( Kanischka-Mahāvihāra ) and a 400 Foot high stupa was erected.

This was the time when Indian Buddhism was in its prime. The connections within the empire encouraged its spread beyond Afghanistan, where Buddhism had already gained a foothold. The emperor Kaniṣka was a major supporter of the spread to the north. He is known as the organizer of the fourth Buddhist council , which gave precedence to the doctrine of the Sarvāstivādin . During this time the transition to Sanskrit as the canonical language took place. Chinese sources still pass on the names of some important missionaries, who mostly also appeared as translators of canonical scriptures .

The missionary history is traditional and passed down through Kharoṣṭ inscriptions .

In the first centuries a. Z., in Central Asia - although mostly desert - Buddhist monasteries arose at some oases in which not only local monks, but also many from Kashmir and Gandhara resided. The cultural colonization of these areas from India took place at the time of the Kushana dynasty. Monasticism in the region developed more in a scholastic direction. The initially dominant Sarvāstivādin school was ousted by Mūlasarvāstivādin .

The spread of Buddhism took place mainly along the trade routes between India and China, the best-known description of which from the classical period is the travelogue of the Xuanzang ( 玄奘 , traveled: 629-45). The two branches of the Silk Road from Balkh to Dunhuang , which had been a center of Buddhist proselytizing since the third century, formed the gateway for the spread of various Buddhist schools to East Asia.

In the east of today's Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan , excavations by Soviet scientists have unearthed various temple complexes (even later). Among other things, in Airtam (17 km from Termez ), Kara-Tepe (cave temple in Termez, with Stupa , probably during the Sassanian Persecution of Buddhists 275 destroyed), Fayaz-Tepe , Ak-Besshim (8 km from Tokmok , 1953-4) and Dalverzin -Tepe (discovered in 1967), which prove the importance of Buddhism in the area, partly through inscriptions by their founders during the Kushana period.

A Buddhist center of the 3rd / 4th centuries Century was Margiana , d. H. the area around the oasis of Merw (near today's Mary (Turkmenistan) ). In the area of Ferghana and Khorezmia Buddhism seems to have found less entrance, although artifacts have also been found there ( Quvā , Balavaste , Ajina Tepe in 12 km from Kurgan-Tübe )

After the invasion of the Hunas (which means a group of the so-called Iranian Huns , probably the Alchon ), the first Buddhist persecution in the region occurred under Mihirakula (d. Approx. 550; Ch .: 摩 醯 羅 矩 羅 ) . As a direct result, the number of Indian Buddhist refugees in the Chinese capital Luoyang rose to around 3,000, which was fertile for Chinese Buddhism. However, Xuanzang describes the Mahāsāṃghika school as flourishing in Bamiyan .

In the region later (6th – 8th centuries), in addition to Buddhism, Eastern Manichaeism and, to a certain extent, Nestorianism , existed side by side, not always without conflict.

Sogdiana

From Sogdia (with the capital Samarkand ), the Kang of the Chinese, several important missionaries came to China early. Buddhism seems to have been largely displaced there by the resurgent Manichaeism in the 7th century.

Ferghana

The remains of a Buddhist temple were found during excavations in Quva in the Fergana Valley .

Balch

There, the Sarvāstivādin-related western Vaibhāṣika school dominated, which was widespread throughout western Turkestan. This represents a link in the transition from Hina to Mahayana. Balch was the capital of Tocharistan in the 7th century and is said to have had many (? Hundred) temples. Excavations in Zang-Tepe (30 km from Termiz) have confirmed the historical accounts.

Eastern region

From the turn of the century, Buddhist activities have been documented in what is now the Chinese province of Sikiang ("Chinese Turkestan").

Hotan

Main article: Kingdom of Hotan

The Hotan oasis on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin is also known as Kustana . It is said to have been colonized by Indians at the time of Aśoka and was economically and culturally the most important place for Buddhism. In the heyday the sphere of influence extended to Niya ( Ni-jang ).

Hotan was a Mahayan center early on, as evidenced by the Book of Zambasta , an 8th century anthology .

The kings maintained an important Gotami monastery . Particularly religious music was cultivated on site. Mahāyāna teachings prevailed. The outlying monastery became the place where birch bark manuscripts were found, which were written in Sanskrit, but written in Kharoshthi script .

With the Islamic conquest of Hotan in 1004, Buddhism was finally ousted, a process that had started in western Turkestan 200 years earlier. The Muslims of Turkic origin living there today have practically no knowledge of the prehistory.

Turkic tribes

Turkic tribes who were familiar with Buddhism from the 6th century onwards without immediately adopting it began to profess it from the early 7th century. The Chinese traveler Ou-k'ong (toured Kashmir and Gandhara 759-64) reports of temples built under Turkic rule.

The Uyghurs, who professed Manichaeism in 762-845, were defeated in Mongolia in 842. Thereupon they evaded to the south, in the process of taking over - and strengthening again - the Buddhist culture also among the invading Turkic peoples.

see also: Empire of the Gök Turks

Kucha

Main article: Kuqa

The oasis of Kuqa (Ch .: 龜茲 or 庫車 ) between Kashgar and Turpan was known in ancient times for its abundance of water. From the 4th century a Tochar dynasty had established itself there. The local Buddhists mostly adhered to the Sarvāstivādin . They were the first to start translating Sanskrit manuscripts into local languages. Maitreya was an object of special reverence. It is the place of origin of the translator Kumārajīva ( 羅什 , 344–413).

Kashgar

Kashgar , west of the Tarim Basin, is referred to as Su-leh in Chinese texts . At the time of Hsüan-tang, the Sarvāstivaādin teaching was still the dominant one. After the rigorous devastation by Muslim conquerors, there are hardly any Buddhist traces to be found today.

Yarkant

Yarkant was known as So-ku during the Han dynasty , later Che-ku-p'o or Che-ku-ka . Mahāyānist teachings predominated.

Karashar

Karashahr (Skr .: Agni ) is the Chinese Yanqi or A-k'i-ni . Around 400, the Hinayana teaching predominated here. At the time of the Hsüan-tsang's journey , the place was probably no longer of any importance.

see also: Site of the Buddhist temples in Shikshin

Loulan

Loulan at Lop Nor , was known as Shan-shan in Han times , later Na-fo-po , Tibetan Nob and one of the most important modern sources for manuscripts. Loulan is obviously a Chinese transcription for the original name Kroraina. The traveler Faxian ( 法 顯 ) reports that Hinayana Buddhism dominated there around 400 , with strict observance of Vinaya .

Turpan

Main article: Turpan , German Turfan Expeditions

Turpan ( 吐魯番 ) was an important center of both Hinayana and Mahayan schools, the traces of which can be traced back to the 4th century. From the 9th century onwards, the region was the heart of the Uighur Empire.

Buddhist literature

The literature of the canon is in a wide variety of languages, mostly, but not only in Sanskrit , but also Prakrit , Tochar , Uighur and the like. a. Dialects preserved. Overall, it covers the entire range of Buddhist contemporary teachings.

Birch bark was often used for writing. After the British Colonel Bower and the French traveler Dutreul first acquired birch bark manuscripts in the 1890s, the systematic archaeological search began soon after. Significant sites of manuscripts of such materials - often lost in the Indian original - are Endere (of the Kingdom of Shanshan ), Donhuang, Loulan Gucheng and the nearby Niya (Ni-jang). The first texts were found through the expeditions of Aurel Stein , Dimitri Alexandrowitsch Klementz , the Japanese Count Ōtani Kōzui and Paul Pelliot .

The not exactly localized finds, the two most important collections today, come from the area of today's Afghanistan. On the one hand the collection of the British Library from the 1st century, u. a. with canonical writings of the Dharmagupta school . Second, the Schøyen Collection , the Norwegian National Library, contains texts from the second to seventh centuries, mostly Mahāyāna writings. The manuscripts found are in Prakrit and Sanskrit and not translated into local languages.

The later manuscripts from the 5th and 7th centuries, translated into Agni and Kucha, have been preserved in Agnean ( Tokhara A ) and Kucharic (Tokhara B). The first translator is “ Dharmamitra of Termiz” (Tarmita). The fragments of the 7th or 8th century found at Zang-Tepe are written in a variant of the Brāhmī script adopted by the Tocharians . The Uighurs adopted this. Your traditional manuscripts contain mainly Mahayana texts, hardly any Vinaya .

literature

General and history

- Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 1. Gale, New York 2004, pp. 120-124.

- Jotiya Dhirahseva: Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Volume 4 (1979), pp. 21-85.

- W. Fuchs: Huei Chao's pilgrimage through Northwest India and Central Asia. In: Preuss meeting reports. Akad. D. W. 1938

- A. v. Gabain: Buddhist Turkish Mission. In: Asiatica - Festschrift F. Weller. Leipzig 1954

- Av Gabain: Buddhism in Central Asia. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden / Cologne 1961.

- Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim: The meeting of Christianity, Gnosis and Buddhism on the Silk Road. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1986, ISBN 3-531-07283-8

- Laut, Jens Peter: Early Turkish Buddhism and its literary monuments. Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 978-3-447-02623-9

- BA Litvinsky: Cultural History of Buddhism in Central Asia. Dushanbe 1968

- BA Litvinsky: Recent Arcaeological Discoveries in South Tadjikistan and Problems of Cultural Contacts between the Peoples of Central Asia and Hindustan in Antiquity. Moscow 1967

- S. Mizuno (Eds.): Haibak and Kaschmir-Smast, Buddhist Cave-Temples in Afghanistan and Pakistan Surveyed in 1960. Kyoto 1962 (archeology)

- Puri, PN; Wayman, Alex (ed.); Buddhism in Central Asia; Delhi; 1987 (Motilal Banarsidass); 352S; ISBN 81-208-0372-8

- Klaus Röhrborn (Hrsg.): Languages of Buddhism in Central Asia: Lectures d. Hamburg Symposium from July 2 to July 5, 1981. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-447-02365-1 .

- Bérénice Geoffroy-Schneiter: Gandhara, The cultural heritage of Afghanistan. Knesebeck, Munich 2002 (Knesebeck), ISBN 3-89660-116-4

- Mariko Namba Walter: Tokharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century ce In: Sino-Platonic Papers , 85 (October 1998)

Literature and manuscripts

- Jens Baarving et al. a .: Buddhist Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection. Oslo 2000-2002

- Günter Grönbold: The words of the Buddha in the languages of the world: Tipiṭaka - Tripiṭaka - Dazangjing - Kanjur; an exhibition from the holdings of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-9807702-4-9

- Simone Gaulier: Buddhism in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Leiden 1976, ISBN 90-04-04744-1 (iconography)

- Richard Salomon: Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara - The British Library Kharoṣṭi Fragments. Seattle 1999.

- Kshanika Saha: Buddhism and Buddhist Literature in Central Asia. Calcutta 1970 (KL Mukhopadhyay); (Diss. Uni Calcutta)

Web links

- Zentralasienforschung.de there: Outlines of the history of inner-Asian peoples

- Study Buddhism: Historical Sketch of Buddhism and Islam in Afghanistan , ... West Turkestan and ... East Turkestan

- Three Brief Essays Concerning Chinese Tocharistan (PDF file; 1.69 MB)

- Nestorianism in Central Asia during the First Millennium ... (PDF file; 134 kB)

- Select Bibliography on Buddhism in Western Central Asia

Remarks

- ↑ XXXIV, v 29; engl. Exercise: W. Geiger, Colombo 1950

- ^ Paragraph after: Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), p. 22f.

- ↑ Described in: G. Tucci et al .: Un editto bilingue greco-arameico di Asoka. Rome 1958

- ^ Trivedi, Vijaya R .; Philosophy of Buddhism; New Delhi 1997 (Mohit); ISBN 81-7445-031-9 , pp. 129f

-

↑ cf. 1) Burrow, T .; Translation of Kharoṣṭ Inscriptions from Chinese Turkestan; London 1940

2) Boyer, AM; Rapson, EG; Senart, E .; Kharoṣṭ Inscriptions discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in Chinese Turkestan transcribed and edited…; 3 parts - ↑ see: Wille, Klaus; The handwritten tradition of the Vinayavastu of the Mulasarvastivadin; 1990, ISBN 978-3-515-05220-7

- ↑ Ta-T'ang hsi-yü-chi (translated variously)

- ↑ first time 1933, 1937, 1964-5; Pukachenkova, GA; Dve stupy na yuge Uzbekistana; in: Sovetskaya arkhelogia 1967, p. 262

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), p. 31f

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), p. 36

- ↑ Nanjō Bun'yū ; A Catalog of the Chinese Translations of the Buddhist Tripitaka…; Oxford 1883, col. 388ff

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), pp. 33f

- ^ Paragraph after: Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), pp. 24, 43

- ↑ cf. Litvinsky, Recent ... (1967)

- ↑ Fa-hsien in: 佛 國 記 ; also Hsüan-Tsang, 250 years later. From: Saha, p. 18.

- ↑ whole (and following) paragraph: Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004), p. 121f

- ↑ travelogue above: Levi, A; Chavennes, E .; L'itenéaire d'Ou-k'ong ; in: Journal Asiatique, Sept.-Oct. 1895, p. 362

- ↑ Saha, p. 7.

- ↑ in his: 佛 國 記

- ↑ Complete section after: Saha, Kshanika; Buddhism and Buddhist Literature in Central Asia; Calcutta 1970

- ↑ Günter Grönbold; The words of the Buddha ...

- ^ Paragraph after: Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (1979), pp. 24, 43, 75