C / 1680 V1 (Great Comet of 1680)

| C / 1680 V1 [i] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

The 1680 comet over Rotterdam

|

|

| Properties of the orbit ( animation ) | |

| Orbit type | long-period |

| Numerical eccentricity | 0.999986 |

| Perihelion | 0.00622 AU |

| Aphelion | 889 AE |

| Major semi-axis | 444 AU |

| Sidereal period | ~ 9360 a |

| Inclination of the orbit plane | 60.7 ° |

| Perihelion | December 18, 1680 |

| Orbital velocity in the perihelion | 534 km / s |

| history | |

| Explorer | Gottfried Kirch |

| Date of discovery | November 14, 1680 |

| Source: Unless otherwise stated, the data comes from JPL Small-Body Database Browser . Please also note the note on comet articles . | |

C / 1680 V1 (Great Comet of 1680) , also known as "Kirch's Comet", was a comet that could be seen with the naked eye around the turn of the year 1680/1681 . Due to its extraordinary brightness, it is counted among the " Great Comets ".

The comet plays an important role in the history of comet research, as it was the first comet to be discovered by a telescope and, for the first time, an exact orbit was determined from its observations . It turned out to be an extreme sun streaker (smallest distance 1.3 solar radii) and also came relatively close to the earth twice.

Discovery story

The comet was made by Gottfried Kirch in Coburg on the morning of November 4th . / November 14, 1680 greg. discovered. He was observing the crescent moon and Mars when he saw a star next to the moon that was not in Tycho Brahe's star catalog . When trying to determine the position of this star, he came across what he later described as "some kind of foggy patch of unusual appearance" and which he either denoted "a nebulous star similar to that in the belt of Andromeda " or a comet held. Indeed, its "nebulous star" was a new comet, and Kirch's accidental discovery went down in history as the first comet discovery with the aid of a telescope.

At the time of its discovery, the comet had not yet formed a tail and could not yet be seen with the naked eye. Two days later the comet had changed its position and a faint ½ ° long tail was visible in the telescope.

The comet was rapidly increasing in brightness and on November 20th it was seen with the naked eye from the Philippines . One day later it was seen in England and the following morning in China with a tail 1.5 ° long. By the end of November it had developed into a noticeable figure. According to JD Ponthio, a tail of 15 ° was observed in Rome on November 27, and just two days later Arthur Storer in Maryland estimated between 15 and 20 °. By the end of the month, increasingly larger tail lengths were reported and the comet appeared "larger" than a first magnitude star .

Proximity to the sun and other observations

At the beginning of December, the comet was getting closer and closer to the sun and was no longer observable from December 7th. On December 18, it passed through its closest point to the sun ( perihelion ) (viewed from Earth, from 11:30 a.m. UT it passed directly behind the solar disk for three quarters of an hour) and developed such a brightness that it was next to the sun in the daytime sky Was seen.

From December 20th it could be seen as a magnificent spectacle in the evening sky . The comet's beauty was enhanced by a shimmering gold tail, it was reported. John Flamsteed reported on December 21st of a beam of light the width of the full moon , extending vertically from the horizon to almost the zenith . Ponthio in Italy estimated the tail length on December 22nd to be 70 ° with a latitude of 3 ° at its end. The comet's head was as bright as a star of the first magnitude, and its tail so long that it could be seen on the western horizon for five hours after the head went under. On December 28, the tail according to Robert Hooke in England reached a length of 90 ° and thus reached over half the firmament . It had a tremendous impact on the public. A flood of publications appeared, mostly spurred on by a rampant fear of comets . Like many of its predecessors, the tail star was seen as a sign of the approaching end of the world , or at least as a warning from God ; in the churches were repentance service held.

In January 1681 the comet showed the first signs of fading, but the tail remained very long and conspicuous: According to Flamsteed, the head was weaker than 3 mag on January 5, but the tail was still 55 ° three nights later. Kirch also reported on January 7th of a (very weak) counter-tail pointing towards the sun, but this observation was not confirmed by anyone else.

At the beginning of February the comet itself could no longer be seen without a telescope, Flamsteed estimated 7 mag. But his tail was still freely visible and Isaac Newton estimated it to be 6-7 ° long. In the second half of the month he was able to make out a tail length of 2 ° with the telescope. The comet was last observed on March 19, 1681.

Scientific evaluation

Of all things, the comet that led superstition to blossom also heralded its end. Numerous astronomers watched the huge tail star with great care. The astronomer Johannes Kepler , who published the laws according to which planets move in elliptical orbits around the sun in 1609 , had still believed that comets move in straight orbits through space. Giovanni Alfonso Borelli assumed in 1665 after his observation of the comet of 1664 ( C / 1664 W1 ), however, parabolic or elliptical orbits. In his Cometographia , published in 1668, Johannes Hevelius also took the view that the comets move on orbits curved towards the sun, but he did not yet think that these orbits orbited the sun.

Georg Samuel Dörffel , a clergyman from Plauen , first raised the question of whether the orbits of comets were not parabolas whose focal point coincides with the center of the sun. He was prompted by his observations of the comet of 1680, which first moved towards the sun and then moved away from it. He recorded his thoughts in a script in the German language (Aſtronomic contemplation of the Great Comet ..., Plauen, 1681).

Had he written his writing in Latin, it might have received more attention, perhaps from Isaac Newton , who also studied comets. Newton had come to the same idea when he developed his general law of gravitation . He came to the conclusion that the orbits of the comets, like the orbits of the planets, must be ellipses with the sun in one focus - not nearly circular ellipses, but extremely elongated ones, which means that the comets are not always visible, but only when they are run through part of their path close to the sun. But this part, Newton added, could also be approximated by a parabola that differs little from an eccentric ellipse near the focal point.

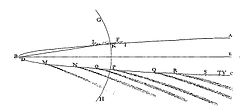

Newton tried to test his hypothesis through a real case. He showed how to calculate a parabolic orbit of a comet from three positions obtained by observation. As an example, he selected three points from Flamsteed's observations of the comet of 1680 and calculated a parabolic orbit from these that matched all other observations so perfectly that there was no longer any doubt that the comet's true orbit would be discovered. Newton published his discovery in the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica , published in 1687 . This also refuted the widespread contemporary belief that the comet from 1680 was two different comets, one that moved towards the sun in November and another that moved away from the sun from December onwards.

The superstition was not completely gone. Even in Newton's time, William Whiston associated the comet with a multitude of mythological and historical catastrophes, between which each should lie 575 years: The Flood in 2916 BC. BC, two periods later the flooding of the Ogygos in 1767 BC. BC, the beginning of the Trojan War in 1192 BC. The destruction of Nineveh in 617 BC. BC, the year of death of Julius Caesar in 43 BC. BC, the beginning of the reign of Justinian I in 531 with many wars, earthquakes and epidemics, the beginning of the Crusades in 1106, and finally the apparition in 1680. In 2255 the end of Western culture should then perhaps be imminent. This compilation was based on an inaccurate calculation of the comet's orbit going back to Edmund Halley with an assumed orbital period of 575 years and was rumored by D'Alembert in the Encyclopédie française and in almanacs in the 19th century . This nonsense only came to an end in 1816 when Johann Franz Encke carried out precise calculations of the orbital elements of the comet from 1680, which showed that its orbital period was not 575 but almost 10,000 years.

While the comet was discovered by Gottfried Kirch in 1680 and named after him, the Tyrolean Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645–1711) must also be remembered, who recorded the apparent path of the comet. During his late departure for Mexico , Kino began his observations in Cádiz late in 1680. Upon his arrival in Mexico City , he published the work Exposición astronómica de el [sic] cometa (1681), in which he presented his observations. Cinema's release was one of the first scientific studies to come out in the New World. There was a dispute with the Mexican polymath and astronomer Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora , who in a manifesto strongly criticized the superstition associated with the appearance of the comet.

Another Jesuit who observed the comet in Mexico and reported about it was the Croat Ivan Ratkaj (1647–1683).

Orbit

The comet runs in an extremely elongated, elliptical orbit around the sun, which is inclined by around 61 ° to the ecliptic . At the point of the orbit closest to the Sun ( perihelion ), which the comet last traversed on December 18, 1680, it was only about 930,000 km from the center of the Sun, that is, it was only about 3/4 of the Sun's radius above the Sun's surface.

Although the comet was undeniably a Sungrazer , it is not a member of the Kreutz group or any of the other larger sunscatter groups. However, comet C / 2012 S1 (ISON) , which dissolved shortly before reaching its perihelion, had similar orbital elements as the comet of 1680 and could have been a second member of its group.

During its passage through the inner solar system , the comet also came relatively close to almost all planets one or more times:

| date | planet | Distance (in AU ) |

Distance (in million km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| February 28, 1679 | Saturn | 1.46 | 218.5 |

| October 12, 1680 | Mars | 0.37 | 55.3 |

| November 30, 1680 | earth | 0.42 | 63.0 |

| December 18, 1680 | Venus | 0.72 | 108.1 |

| December 26, 1680 | Mercury | 0.24 | 35.2 |

| January 3, 1681 | Mars | 1.42 | 212.5 |

| January 4, 1681 | earth | 0.49 | 73.2 |

| February 3, 1681 | Venus | 1.02 | 152.7 |

| September 8, 1681 | Jupiter | 1.45 | 217.6 |

In particular, the approaches to Saturn and Jupiter caused slight changes in the shape of the comet's orbit. At the moment (2014) the comet is about 255 AU / 38 billion km from the Sun, it is even further away at 2.3 km / s. Whether it will ever return to the inner solar system cannot be said, possibly only after tens of thousands of years.

Flyer on the "wonderful incomparable Comet"

Shortly after the comet appeared, a flying leaf illustrated with a large picture appeared

Illustration and description of the wonderful incomparable

COMETE.

Who first appeared at the beginning of the winter month before the sun rose /

and now, after the same downfall, lets himself be seen terribly.

The approximately 20 × 30 cm large picture shows the comet, the wide-spread tail of which extends over most of the sky. People stand tightly packed on the hills in front of the walls of Nuremberg and marvel at the event, some with telescopes . The text of the leaflet begins with a reference to the Bible, to God's long-suffering and his invitation to repent in the face of the heavenly torch, rod and sword:

One finds both in holy scriptures / as well as other credible histories /

that so often Almighty GOD is determined to punish the sins of some earth inhabitants /:

He first announces this out of mild paternal long-suffering either through true prophets /

or terrible miracles;

Has this warning been fruitful / and an eyferige penance and conversion has taken place /

then the threatened punishment is averted ...

[...]

As if He has now again in the high heaven / a terrible torch, ruthe and heavy weight /

to a benevolent one Warning / issued for the still imminent disaster;

So that ... this cruel and terrible

Comet, who is incomparably admired by the star experiences / because of his shape and movement, / can cast out

some horror and change in the sin-hardened minds /

[...] But

it is this wonderful, incomparable Comet ... in the sign of the lion /

in which the war planet Mars was also at that time [...]

then the following days in the sign of the virgins ... with an ever increasing /

but was seen weak tails because of daybreak.

Then the passage of the comet behind the sun observed in the Christian month is described, according to which

at the beginning of the night / with a very long pale white tail /

very splendidly broken out / and those earth- dwellers /

as a heavy load of revenge and a rod of wrath from the Most High of GOD / presented

After other, astonishingly precise observations of the comet, the author states that "to the astonishment of those with astute experiences" it not only declined , but also rose more and more to the north.

Finally - in a strange contrast to the heavenly warning - the distance and size of the comet is estimated: its body , although only a 3rd mag star, is estimated by astronomers to be hardly smaller than the earth, but the extent of the 60 ° long tail is estimated by many one hundred thousand German miles (several million km).

Pierre Bayle's Thoughts on the Comet of 1680

In 1682, the enlightener Pierre Bayle published his first book Lettre sur la comète de 1680 ("Letter about the comet of 1680"), which was expanded in 1683 as Pensées diverses sur la comète de 1680 ("Different thoughts on the comet of 1680"). There he contradicted the superstitious notions associated with comets and promoted the idea that all knowledge must be constantly and critically checked. Bayle defended the Christian faith, but at the same time drafted the foundations of a non-religiously determined morality or ethics, whereby - contrary to the general opinion at the time - he assumed that an atheist does not necessarily have to act immorally.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Stefan Krause: Komet Kirch (C / 1680 V1). Retrieved May 31, 2014 .

- ^ André Walther: From the (significance) of the comets - The comet of the year 1680/81 in the mirror of contemporary pamphlets. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014 ; accessed on May 31, 2014 .

- ^ DAJ Seargent: The Greatest Comets in History: Broom Stars and Celestial Scimitars . Springer, New York, 2009, ISBN 978-0-387-09512-7 , pp. 112-115.

- ↑ Ch. A. Semler : Oddities from the ächiſchen literary history . Abendzeitung, 266, Dresden, November 7, 1818

- ↑ Joseph Johann von Littrow : The miracles of heaven, or common understanding of the world system . Vol. 2. Stuttgart, 1835., pp. 281-282.

- ^ HE Bolton: Kino's Historical Memoir of the Pimería Alta . Cleveland, OH (USA): Arthur H. Clark, 1919. Reprint 1949.

- ↑ Manifiesto philosóphico contra los cometas despojados del imperio que tenían sobre los tímidos , Mexico 1681.

- ^ N. Petrić: Description of the AD 1680 comet observed in Mexico by the Croatian Jesuit Ivan Ratkaj . In: Hvar Observatory Bulletin , Vol. 18, No. 1, 1994, pp. 37-40. ( bibcode : 1994HvaOB..18 ... 37P )

- ↑ C / 1680 V1 (Great Comet of 1680) in the Small-Body Database of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (English).

- ↑ Tony Hoffman: A SOHO and Sungrazing Comet FAQ. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 4, 2013 ; accessed on May 31, 2014 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Gary W. Kronk's Cometography - C / 2012 S1 (ISON). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 28, 2012 ; accessed on May 31, 2014 (English).

- ↑ SOLEX 11.0 A. Vitagliano. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015 ; accessed on May 2, 2014 .

- ^ Facsimile from Wilhelm Foerster : The exploration of the universe. In: Hans Kraemer (ed.): Universe and humanity. Volume III, Verlag Bong & Co., Berlin and Leipzig 1903, p. 261/62.

- ↑ see e.g. B. Theodor G. Bucher : Between atheism and tolerance. On the historical impact of Pierre Bayle (1647 - 1706). in: Philosophical Yearbook . 92nd volume, 1985, p. 353 ff. (PDF 1.3 MB)