Caritas Pirckheimer

Caritas Pirckheimer , before 1483 Barbara Pirckheimer (born March 21, 1467 in Eichstätt , † August 19, 1532 in Nuremberg ) was the abbess of the Poor Clare Monastery in Nuremberg and famous for her humanistic education. She resisted the city council's attempts to dissolve the monastery against the will of the nuns. She received support from Philipp Melanchthon .

Sources

Memorabilia

While there is little reliable information about the childhood of the Pirckheimers up to their election as abbess of the Poor Clare monastery, their actions as abbess at the time of the Reformation can be traced in Nuremberg. As a critical observer, she wrote down all events in the form of a chronicle from 1524 to 1528 . Constantin Höfler, who published the manuscript in 1852, gave it the title "Memories".

Letters

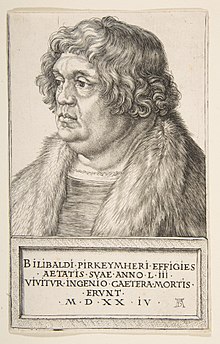

Caritas Pirckheimer was in lively correspondence with many personalities of their time, including her brother Willibald , Erasmus von Rotterdam , Conrad Celtis and Sixtus Tucher . A letter from her to the painter Albrecht Dürer has also come down to us. In the received letters to and about the abbess, her education is particularly recognized. She discussed important matters with her brother Willibald. However, their relationship was not a one-sided relationship, as Caritas also advised her brother and discussed theological issues with him. In addition to Willibald Pirckheimer, the council lawyer and former rector of the Wittenberg University Christoph Scheurl, and the monastery caretaker Kaspar Vorteilel , a Lutheran, Sixtus Tucher, the provost of St. Lorenz , received numerous letters from the abbess. He maintained a close friendly relationship with Pirckheimer.

Life

childhood

Barbara Pirckheimer was born on March 21, 1467 in Eichstätt as the daughter of the lawyer and diplomat Johannes Pirckheimer and grew up in a patrician family in Nuremberg . Her father was active as a councilor to the Eichstatt Bishop Wilhelm von Reichenau. She received her baptismal name Barbara from her mother of the same name, who was born in Spoonwood . She died giving birth to her thirteenth child. Barbara Pirckheimer was the oldest of the siblings. A total of eight daughters reached adulthood, but only one son, Willibald. Six daughters also entered a Poor Clare or a Benedictine convent ; a daughter married. The father spent the last years of his life as a widower in the barefoot monastery and was ordained a priest four years before his death in 1497 .

At the age of twelve, Barbara came to her grandfather Hans Pirckheimer in Nuremberg. The grandfather's second wife, Walburga Pirckheimer, who was childless herself, and the grandfather's unmarried sister, Katharina Pirckheimer, were considered to be very well educated and taught Barbara at home before attending the convent school. Her grandfather, a councilor who studied humanism intensively, was also involved in her upbringing . He also taught Latin to his granddaughter .

For further education and lessons, Barbara finally came to the monastery school of the Poor Clares. This was not an unusual step as the four Latin schools in Nuremberg only accepted boys. It is documented that after two years of teaching at this school, Barbara was able to understand and speak Latin. However, contrary to her wishes, she was only allowed to enter the novitiate when she reached the minimum age (16 years) . Around the year 1483 Barbara was accepted as a novice of the convent of the Poor Clares and was given the religious name Caritas (Latin for "charity") to dress .

First monastery years

Mainly daughters of the Nuremberg patriciate lived in the Klarakloster, including aunts from Caritas. Her biological sister Klara joined the community in 1491 and her nieces Crescentia and Katharina Pirckheimer followed in 1513.

Caritas Pirckheimer, however, was still in lively correspondence with Willibald, who was allowed to visit her at the cloister from time to time . Not only he, but also his friends, who belonged to the humanistic circle, exchanged views with her. Among them was Christoph Scheurl, who wrote a song of praise for the Pirckheimer family. Conrad Celtis dedicated his edition of the works of Roswitha von Gandersheim to Caritas as well as a Latin ode that he wrote in 1502. It is thanks to him that Caritas became a public figure as a cloistered nun, transfigured into a virgo docta of national standing.

Willibald sent Caritas humanistic books for the monastery library, including by Erasmus von Rotterdam , which gave her and her fellow sisters the opportunity to take part in the current discussion behind the monastery walls.

The Poor Clares received support from Anton Tucher , who donated an organ to the convent in 1517 . Musical instruments in churches were rare at that time. This year can be seen as the highlight of the monastery history; the monastery had such a good reputation that many patrician families entrusted their daughters to it.

Caritas Pirckheimer as abbess

From 1490 on, Caritas Pirckheimer taught the convent students as a so-called child master , organized the monastery library and then took over the office of novice master until she was elected abbess on December 20, 1503 . The convent consisted of about 60 to 70 sisters.

The Franciscan theologians Heinrich Vigilis and Stephan Fridolin, as well as the exchange with Sixtus Tucher and the reading of the church fathers , especially Hieronymus, were formative for their spirituality .

As abbess, Caritas attached great importance to the religious education of the nuns. All the sisters received Latin lessons. They should understand the language in which they prayed and also have the ability to study the Bible as translated from the Vulgate . A comprehensive, humanistic education should enable the sisters to come to terms with their faith and, as a result, a deep piety.

Furthermore, the abbess, together with the caretaker, administered the property of the monastery. She prepared a monastery account for the council and decided on the use of incoming interest payments . It also took a long time to write letters or thank you letters for donations received.

Even before the beginning of the Reformation , the monastery’s financial situation had deteriorated drastically. The reason for this lay in the falling income and the extremely increased expenditure. The expansion of the Klarakirche and the subsequent renovation work on the monastery buildings caused high costs . In a letter to the Pope in 1505, Caritas described the threatening situation of the Convention and therefore asked for an indulgence to be granted . In this way , an incentive was created for less well-off Nuremberg residents who could not set up foundations to make a contribution to the preservation of the monastery. Rome then sent approval of a letter of indulgence .

However, the financial situation of the Klarakloster worsened again when the council decided in 1525 to levy a consumption tax ( Ungelt ) on beer and wine. Because the sisters brewed beer themselves, they clearly felt the consequences of the decree.

The continued existence of the Poor Clare Monastery was fundamentally questioned when the Reformation was introduced in Nuremberg in 1525. All monasteries in Nuremberg should be closed. The Klarakloster could initially continue to exist. The council forbade the admission of new sisters and monitored compliance with this prohibition.

Freedom of conscience - renouncing confession

After the Nuremberg Religious Discussion of March 3-14, 1525, Nuremberg turned to Lutheran teaching. Only five days later two councilors appeared with the news that the previous confessors and preachers who belonged to the Franciscan order were no longer allowed to exercise their offices. The Klarakloster had been associated with the barefoot monks for more than 250 years. They brought counter-Reformation writings with them, which Caritas selected as a table reading and then distributed throughout the city. The council had decided that only Lutheran-minded clergy were allowed to preach in order to convince the sisters of the new doctrine. The abbess counted a total of 111 sermons from Andreas Osiander , with whom she had last had a four-hour discussion.

Caritas fought against the council's decision on behalf of all sisters. She replied that there had never been any complaints about the Franciscans and that their religious rule provided for pastoral care only by religious priests . The councilors insisted that the resolution be implemented, but the sisters decided not to go to confession in order not to have a confessor prescribed. The abbess appealed for freedom of conscience and that no one could be forced to confess . Caritas presented its position in its "Memorabilia" as follows:

- It would be “better and more useful for us to send an executioner to our monastery to cut off our heads than for you to send us a full, drunk, unchaste priest. One does not force a servant or a beggar to confess wherever his rule will. We would be poorer than poor, should we confess to those who themselves have no faith in confession, should we receive the venerable sacrament from those who abuse it so heinously that it is a shame to hear about it, we should obey them who are not obedient to the Pope, the Bishop, the Emperor, or the whole holy Christian Church. Should they also abolish the beautiful divine service and change it according to their heads, then I would rather be dead than alive. "

Due to the introduction of the Reformation in Nuremberg, the nuns had to do without Holy Mass , the sacrament of penance and the sacraments of death . Despite this, the abbess tried to continue the spiritual life.

Ursula Tetzel, a native of Nuremberg, soon turned to the city council and applied to be allowed to bring her daughter Margaret out of the Poor Clare Monastery. She said she wanted to teach her the gospel at home and then give her a choice of whether or not to return to the monastery. In a petition to the city council, Caritas Pirckheimer stated that Margaret Tetzel wanted to stay in the monastery and that the monastery life otherwise followed the example of the early community, i.e. was in harmony with the Gospel.

Dominicus Schleupner , preacher of St. Sebald , suggested that the council ask Caritas to leave the city. He disliked the lively correspondence that she conducted with both clergy and other convents. But if the magistrate succeeded in convincing them of the new doctrine, not only the Klarakloster would join the Reformation, but also other convents at the same time. It was known that many of the surrounding monasteries turned to Caritas for assistance and valued their opinion. That is why the council persisted in its persuasion.

Adherence to religious vows

In the week of Pentecost in 1525, the council passed another resolution to the Nuremberg monasteries, which included the following five demands:

- The abbess should release all sisters from their religious vows .

- Every sister should be free to leave the convent, and family members to take their daughters out of the convent. The council undertook to provide for the livelihoods of those who had left.

- Instead of the habit , civil clothing should be worn.

- The council should receive a list of all income, possessions and other valuables of the convention.

- Finally, the previous speech windows, covered with black fabric, were to be replaced on the cloister grille so that the visitor could be sure that no one else was overhearing the conversation.

As long as the concerns of the magistrate concerned secular matters, Caritas was willing to compromise. When it came to spiritual questions, however, she did not hesitate to contradict if necessary. However, Caritas did not want to challenge obedience to the magistrate on principle .

The abbess first discussed the situation with each sister and asked for their opinion. She then protested against the abolition of the speech window, as she saw it as a gradual opening of the enclosure , as well as against the cancellation of the vows. Caritas emphasized that the nuns had made a promise not to her but to God.

Only one of the sisters, Anna Schwarz, left the convent voluntarily. She sympathized with the Reformation ideas. There is a receipt on which she certified on March 10, 1528 that she had received her dowry back. Until the convent died out, she was the only nun who took this step.

Public pressure

In the years of the Reformation, the Nuremberg population had a negative attitude towards monasteries. Religious were blamed for moral misconduct and ignorance of the Bible. Thanks to this generalization, the Klarakloster also fell into disrepute, although no violations of the rule were known in this convent and the Poor Clares had studied the Bible. There were riots. For example, some citizens threw stones over the rood screen in the choir room while the Poor Clares were praying their hours . Caritas resisted the slander and threats. She encouraged her fellow sisters to keep their vows even when services were disrupted, the cemetery was trashed and church windows were broken.

The situation finally escalated on the day before Corpus Christi in 1525, when Margaret Tetzel, Katharina Ebner and Klara Vorteilel were forcibly abducted from the convent by their mothers after the daughters had not been persuaded to voluntarily leave the Klarakloster in previous attempts. The council stood behind the mothers and did not intervene. The women saw themselves in the right and invoked the obedience that children owe their parents. All verbal attacks on the part of the mothers were able to refute the daughters with passages from the Bible. However, Caritas had no choice but to release it, as it was threatened with evacuation of the monastery, if necessary with violence.

Melanchthon's meeting with Caritas Pirckheimer

In the spring of 1525, Willibald Pirckheimer wrote a letter to Melanchthon (only preserved in fragments) and asked him to intervene on behalf of the Nuremberg Poor Clares. Pirckheimer made it clear that he himself was critical of the monastic life, which two of his daughters had chosen as a way of life. In November of this year Melanchthon was to visit Nuremberg to build and inaugurate a new grammar school . Caritas Pirckheimer asked Kaspar Vorteilel to arrange a visit to Melanchthon in the Poor Clare Monastery, which was realized. Caritas Pirckheimer reported on the course of this conversation in the “Memorabilia”. She showed herself to be familiar with Reformation theology and emphasized in particular that the Poor Clares did not rely on their own works, but on the grace of God. In contrast to Melanchthon, she insisted that monastery vows are eternally binding. The conversation ended amicably.

In relation to the City Council of Nuremberg, Melanchthon criticized the withdrawal of the confessors and the kidnapping of three Poor Clares from the monastery against their own will. Melanchthon denied the parents the right to force a religious woman to leave the convent. Furthermore, it is not in Luther's sense to destroy the monasteries. Due to Melanchthon's intervention, the city council refrained from continuing to use force against the Klarakloster.

Last years of life

In 1529 Pirckheimer celebrated the 25th anniversary of her ordination as abbess and the 50th anniversary of her profession . Katharina Pirckheimer, her niece, wrote a letter to her father, Willibald, who reported in detail about the course of the celebrations. He himself had a barrel of wine and his silver dishes brought to the monastery. Juliana Geuderin, Caritas' only married sister, also donated trout and sweets on the special day. The gifts that the convent received for the celebration show that Caritas maintained close contact with her family.

Caritas beat the dulcimer and old and young sisters danced. This shows how strongly the convent felt itself to be connected and how a lively atmosphere was able to maintain itself within the monastery walls. Due to her personality, Caritas made a significant contribution to this.

Aside from the celebrations, it was reported that the abbess was struggling with health problems. One year later, in 1530, her brother Willibald died. Caritas followed him on August 19, 1532. She was 65 years old. The exact cause of death is unknown, but there are reports that she had suffered from painful stones and gout for some time .

Caritas Pirkheimer was buried in the nuns' cemetery behind the church, and her grave was located there in 1959. In 1960, her remains were transferred to the choir of the former monastery church of St. Klara .

Another fate of the Convention

Her biological sister Clara took over her position. Most recently, Caritas' niece Katharina Pirckheimer presided over the convent as abbess. The successors tried to continue to oppose the decisions of the council; but without success. In 1596 the last clarissess died in Nuremberg. Caritas could not prevent the destruction of the Klarakloster in the long term, but at least it managed to ensure that the convent remained in existence until the death of the last Clarissess and was never handed over to the council voluntarily.

reception

The Academy Caritas-Pirckheimer-Haus in Nuremberg is an archbishop's foundation which, in line with its namesake, aims to “strengthen the personal conscience in order to face the questions of the time in open dialogue and the answers to the design of the church and To bring in society. "

Leo Weismantel took Caritas Pirckheimer's biography as the basis of his story Die Lesten von Sankt Klaren (1940).

Works

- The edition by Josef Pfanner and August Syndikus includes the abbess's original texts, some of which are written in early New High German and some in Latin. It consists of four volumes:

- Volume 1: The Prayer Book of Caritas Pirckheimer (1961)

- Volume 2: The "Memories" of Caritas Pirckheimer (1962)

- Volume 3: Letters from, to and about Caritas Pirckheimer (1967)

- Volume 4: The grave of Caritas Pirckheimer (1961)

- Georg Deichstetter (Ed.): "The Memories" of the Abbess Caritas Pirckheimer of the St. Klara Monastery in Nuremberg. Transferred from Benedicta scrap. St. Ottilien 1983

- Georg Deichstetter (ed.): Letters from the Abbess Caritas Pirckheimer of the St. Klara Monastery in Nuremberg. Transferred from Benedicta scrap. St. Ottilien 1984

literature

- Anne Bezzel: Caritas Pirckheimer. Abbess and humanist. Small Bavarian biographies . Regensburg 2016

- Georg Deichstetter (Ed.): Caritas Pirckheimer. Religious and humanist - a role model for ecumenism. Festschrift for the 450th anniversary of death . Cologne 1982

- Claudio Ettl / Siegfried Grillmeyer / Doris Katheder (eds.): Caritas Pirckheimer and their house. Thoughts on the 550th anniversary . Edition cph Volume 4. Würzburg 2017.

- Ursula Hess: Oratrix humilis. The woman as a letter partner of humanists, using the example of Caritas Pirckheimer , in: Franz J. Worstbrock (Ed.): The Letter in the Age of the Renaissance (Communication from the Commission for Research on Humanism, 9), Weinheim 1983.

- Martin H. Jung: Philipp Melanchthon and his time . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010. ISBN 978-3-525-55006-9 .

- Gerta Krabbel : Caritas Pirckheimer. A picture of life from the time of the Reformation. Catholic life and church reform in the age of religious schism. Issue 7. Münster 1982

- Lotte Kurras, Franz Machilek: Caritas Pirckheimer 1467–1532. An exhibition by the Catholic City Church in Nuremberg. Imperial Castle Nuremberg June 26th - August 8th 1982 . Prestel, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-7913-0619-7

- Harald Müller: Habit and Habitus: Monks and Humanists in Dialog . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006. ISBN 978-3-16-149123-8 .

- Karl Schlemmer: Caritas Pirckheimer. The pious people of Nuremberg and the abbess of St. Clare. Nuremberg as a religious city in the lifetime of Caritas Pirckheimer 1467–1532 . Münsterschwarzach 1982

- Wolfgang Wüst : Doomed to Extinction? Institutional and mental crisis management in southern German monasteries and foundations in the age of the Reformation , in: Mareike Menne / Michael Ströhmer (ed.): Total Regional. Studies on early modern social and economic history. Festschrift for Frank Göttmann on the occasion of his 65th birthday , Regensburg 2011, pp. 71–86.

- Wolfgang Wüst: Caritas Pirckheimer (1467-1532). The contentious and intellectual opponent of the Nuremberg Reformation , in: Thomas Schauerte (Ed.), New Spirit and New Faith. Dürer as a contemporary witness of the Reformation. Catalog for the exhibition of the city of Nuremberg in the Albrecht-Dürer-Haus from June 30th to October 4th 2017 (series of publications of the museums of the city of Nuremberg 14) Petersberg 2017, pp. 52–65, 206–216, ISBN 978-3-7319- 0580-6

- Sonja Domröse: Caritas Pirckheimer - An abbess in the resistance . In: Sonja Domröse, Women of the Reformation, Göttingen 2017, 101–114. ISBN 978-3-525-55286-5

reference books

- Ludwig Geiger: Pirckheimer, Charitas . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 26, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1888, pp. 817-819.

- Gabriele Lautenschläger: Pirckheimer (Pirkheimer), Caritas. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 7, Bautz, Herzberg 1994, ISBN 3-88309-048-4 , Sp. 626-628.

- Bernhard Ebneth: Pir (c) kheimer, Caritas (Christian name Barbara). In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-00201-6 , p. 474 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Pirckheimer, Caritas OSCI. In: Author's Lexicon . Volume VII, Col. 697 ff.

Web links

- Caritas Pirckheimer in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Testimonials in German-speaking countries

- Digitization of the memorabilia

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 101 .

- ↑ a b Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 102 .

- ↑ a b c Bernhard Ebneth: Pir (c) kheimer, Caritas .

- ↑ Harald Möller: Habit and Habitus . S. 318-319 .

- ↑ Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 104 .

- ↑ Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 108 .

- ↑ Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 109 .

- ↑ Martin H. Jung: Philipp Melanchthon and his time . S. 41 .

- ↑ Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 109-111 .

- ↑ a b Sonja Domröse: Women of the Reformation period . S. 111 .

- ↑ a b c Martin H. Jung: Philipp Melanchthon and his time . S. 42 .

- ↑ History and order. In: CPH Nuremberg. Retrieved May 28, 2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pirckheimer, Caritas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pirckheimer, Charitas; Pirkheimer, Caritas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Abbess of the Nuremberg Klarakloster |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 21, 1467 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Eichstatt |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 19, 1532 |

| Place of death | Nuremberg |