Patriciate (Nuremberg)

The patriciate of the imperial city of Nuremberg , the families entitled to the Inner Council, represented the actual power center of Nuremberg until the French occupation in 1806.

Patricians had developed in other German imperial cities as well as in northern Italian cities since the 11th century from the former local nobility or the local ministry . They called themselves “genders”, the term patricius only appears later in Latin documents . Since about the middle of the 14th century, economic activities, long-distance trade, mining companies and financial transactions of the Nuremberg patricians led to the urban and rural nobility becoming increasingly distant from each other. Nevertheless, the Nuremberg families remained viable and carried knightly coats of arms.

From 1256 until the French occupation and the subsequent incorporation by the Kingdom of Bavaria on September 15, 1806, Nuremberg was ruled by the council, whereby until 1427 many competencies in the city and the surrounding area still lay with the burgraves of Nuremberg who were appointed from 1105 . After the purchase of the burgrave office in 1427, the council had sole control of the city and the immediate vicinity.

The council was divided into the “Inner Council” and the “Great Council”. The Inner Council represented the actual center of power and the owner of the sovereignty . In it - in addition to only eight representatives of the trades - only the "advisable" families were represented, who thereby formed the patriciate of the city. The imperial city of Nuremberg called itself - like other free and imperial cities or the Italian city-states - itself as a " republic " (res publica) . In addition to the reference to the Roman model, the term here also means the contrast to the otherwise common monarchical forms of government. However, “republic” must not be equated with “ democracy ”. As a bourgeois republic with an aristocratic constitutional order (also known as the " aristocratic republic " by historical scholarship ), Nuremberg did not have feudal rule on the basis of feudalism despite such a state organization , but formed an early modern civil society .

history

origin

The families entitled to the council, who - albeit only since the Renaissance - also called themselves patricians after the Roman model , were the politically, economically and socially leading families of the imperial city. Most of them came from the unfree ministry . After the fall of the Staufer Empire around 1250, families of the imperial ministers from the surrounding area, such as the Pfinzing , Stromer , Haller , Muffel or Groß from the imperial estate (Terra Imperii) they had previously managed, moved to the city, while the former governors of the Hohenstaufen emperors, the burgraves from Nuremberg from the house of Hohenzollern , appropriated large territories in the vicinity of Nuremberg. But tensions soon arose between the Council of the Free Imperial City and the Burgraves, who moved their residence from the Nuremberg Burgrave Castle to the Cadolzburg as early as 1260 . After the Burggrafenburg was destroyed in 1420 by Duke Ludwig VII of Bavaria-Ingolstadt , the Hohenzollern sold the castle, the surrounding area and the burgrave office to the city council in 1427 and thus finally left Nuremberg. From then on, the city was ruled directly by the Inner Council , which was recruited from the patrician families . The two margraviates Brandenburg-Ansbach and Brandenburg-Kulmbach subsequently formed from the territories of the Hohenzollern . During the First and Second Margrave Wars , they tried in vain to regain their influence over the wealthy imperial city.

Council rule

The council, first mentioned in 1256, formed the first rules around 1285, which were codified as customary law around 1320. The merchant families who had become wealthy through their trade were represented in the city council and initially appeared as “families”. The number of members and eligible families changed over the centuries. In later times in particular, some craftsmen's guilds had a certain say in the matter , but never (unlike in the cities of Magdeburg or Luebian law, for example ) became part of the real council capacity. In contrast to the Cologne Richerzeche , the guild of rich patricians, which was disempowered by the craftsmen's guilds as early as 1396, the Nuremberg city-state remained the prime example of a patrician city-republic until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Similar to the Republic of Venice , it was under the oligarchical rule of a closed circle of patrician families and, like there, the constitution was determined by a finely tuned balance of power between the influential "sexes" and the individual government organs (cf. Constitution of the Republic of Venice ) . The principle of careful balancing of power and mutual control between the various bodies was always observed.

No family was allowed to have more than two members in the council (senators) , membership was mostly lifelong, but the councilors were formally re-elected every year in May, later on Easter Tuesday. The election process was complicated, but the result was always voted on beforehand. Two consuls presided over the council, called "elder" and "junior mayors"; unlike the ancient Roman consulate , these rotated not annually, but monthly and were purely honorary positions. The senior mayor was the formal head of the city (duumvir primarius) and appeared as such on imperial visits. A Septemvirale was elected from the "older mayors" , seven people who formed the actual government of the city and were also called the College of Elderly Men . From their midst, the three captains were appointed: the “Foremost Losunger ” (the highest public office in the imperial city, which had control over the finances) and his deputy, the younger Losunger . They were entrusted with the city treasury and the maintenance of the seals and letters of freedom. They were no longer allowed to trade or trade. Third was the "captain" who was responsible for warfare and construction. If the foremost Losunger died, the younger Losunger followed him and the captain became the younger Losunger. The more ceremonial office of the " Reichsschultheiss " represented the emperor in the city and formed the top of the judiciary. Other honorary positions were the “Crown Guardian and Custodian of the Imperial Regalia ” and the “Caretaker of the Twelve Brothers House Foundations ” .

Since the beginning of the 14th century, the “Council of the Named” (or “Great Council”) was added to the actual “Council”. This included the gentlemen “named” (ie appointed) by the councilors, mostly influential representatives of the craftsmen's guilds or tradesmen. The council of the named met only at the convening of the "Inner Council". The "named" were not considered to be "able to advise" (for the "Inner Council"), so they were not considered part of the (patrician) city regiment. However, around the patrician families there was another group of respected trading families who were referred to as "Erbare". Their relatives were "capable of judging", meaning they could preside over a court under the authority of the Council. The patrician families “capable of counseling” also entered into marriages with the “heritable” families, and later some families from their circle were accepted into the “inner council” and thus into the patriciate as successors for extinct generations.

The city temporarily had up to eleven administrative offices in the surrounding area , through which it administered its imperial territory . Mostly patricians officiated as carers at the nursing castles. They were subordinate to one of the Septemviri who was appointed "Prefect of the Provinces". In addition, around 40 families and a number of institutions of the council, including above all the Heilig-Geist-Spital and, after the Reformation, the “Nuremberg Landalmosen”, owned extensive manors and subjects subject to tax in the Nuremberg area.

City nobility

In the beginning there were no big differences between the landed gentry and the city gentry . The oldest families built residential towers in the city, as did the ministerials in the country. Of the 65 “ dynasty towers ” that existed in Nuremberg around 1430, only the Nassau house is still preserved today, unlike in Regensburg , for example, where there are even more examples. But since about the middle of the 14th century, the paths diverged. As a rule, the new city nobility achieved great wealth through trade , especially in spices and cloths, with trade connections reaching as far as Cologne and Flanders, Lyon, Bologna and Venice, also to Bohemia, Austria and Hungary, and also through lucrative interests in mining , especially in Upper Palatinate , Thuringia and Tyrol , as well as through financial transactions. The wealth of the patriciate gradually enabled him to found an urban aristocracy . Patricians were merchants, but - in contrast to those who sold “by yard , pound and lot ” - they devoted themselves exclusively to wholesale and long-distance trade .

The land-based noble families of the Franconian knight circle , who lived on the rather modest taxes from their manors , provided they did not hold lucrative court offices or military positions, often took credit from the rich Nuremberg patricians. In return, however, they denied their equality and thus also the ability to hold colleges and tournaments, as the merchants no longer led a chivalrous way of life in their eyes and therefore, regardless of their sometimes aristocratic origin, would have "forfeited" their class affiliation . From their proud castles they looked down half haughty, half disapprovingly at the “ pepper sacks” that worked in their trading offices within the city walls. These in turn fought - in league with other cities as well as the princes - the emerging robber baronism of the impoverished land nobility, such as the Schnapphahn Thomas von Absberg , who had several Nuremberg merchants on his conscience, in the Franconian War of 1523.

Since the knight nobility did not allow the patricians to attend the aristocratic tournaments , the patricians' sons regularly and almost demonstratively carried out so-called " journeyman's stings ", festive knightly lance stings on the large market (today the main market) to underline their rank, the last time in the year 1561. The patriciate also began to found their own monasteries, which served them to care for younger children as well as burial places, for example the Carmelite monastery by the Peßler family in 1287 , the Dominican monastery ( Katharinenkloster ) by the Neumarkter and Pfinzing in 1380, the Carthusian monastery of the merchant Marquard in 1295 Mendel and in 1412 the Terziarinnenspital by the Poor Clare Abbess Katharina Pfinzing. In 1343 the patrician Konrad Groß participated in the founding of the Cistercian monastery Himmelthron in Großgründlach and in 1345 also founded the Pillenreuth monastery for the Augustinian choir women . As early as 1331 he founded the Heilig-Geist-Spital in Nuremberg . The last monastery to be founded in 1422 was the Gnadenberg Monastery in Upper Palatinate , which was donated to the Order of the Birgit . Although it was not in Nuremberg's sphere of influence, it was donated by the Count Palatine von Neumarkt, albeit with the strong support of the Nuremberg patricians, especially the princes , and the city held the patronage of the monastery until the Reformation.

Many patrician families had the emperor individually confirm their nobility quality through imperial nobility or coat of arms letters, often combined with improvements in coat of arms and crowns , often against payment. To demonstrate that they felt noble, other families added an addition to their original family name with “von” and the name of a purchased country estate. In many cases they later succeeded in having this arbitrary addition confirmed by the emperor as a title of nobility .

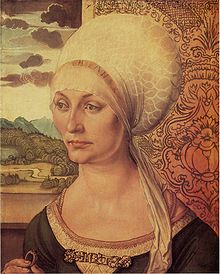

The marriage rules were restrictive, people mostly kept to themselves, although Elsbeth Tucher, for example, portrayed by Dürer, came from a rather modest background. Connubium with the landed gentry took place rather seldom, not only because of the class reservations of the knight families , but also because their possessions were fief-bound and they could therefore not offer the merchants an increase in their wealth. The knights also seldom had cash and never useful trading contacts. Nonetheless, there were connections that brought the patricians at least prestige, for example the mother of the famous founder Konrad Groß (from the wealthy council family Groß ) was born von Vestenberg .

Cooptation

Due to the extinction of many urban aristocratic families in the course of the late Middle Ages, one was forced to supplement the council by co-opting new "respectable families". Some old council families also emigrated from Nuremberg.

“Honesty” was initially considered to be a second class ; later some of their families, which were distinguished by their wealth and marrying into the older patrician families, were also assigned to the patriciate. In this way, in the 15th century, twenty-two new families were promoted to councilors, including the soon-to-be influential Kreß , Rieter and Harsdörffer . From the handicrafts class, only the Fütterer made it into the Inner Council after they had attained considerable prosperity through financial transactions and publishing. In many cases, families who had moved from Upper German cities, such as the important Welser from Augsburg , the Ehinger from Ulm and Memmingen , as well as a number of families from the area around Lauingen in Swabia, were co-opted into the council, including well-known families like the Imhoff from 1350 and the Paumgartner from 1396 .

The circle of eligible families was finally established with the enactment of the dance statute of 1521 and the patriciate of forty-two families closed off like a box. After this decree, the blood principle of the "enjoying family" determined Nuremberg society and politics, because only these forty-two families were eligible. (A similar settlement had already taken place in the Republic of Venice , with which they had trade connections, as early as 1297, where since then only the nobilhòmini have been admitted to the Great Council of the Republic. Nevertheless, the Venetian patrician families remained almost always merchants until the end of the Republic in 1797, different from Nuremberg.)

From 1536 to 1729 only the key fields were co-opted. Due to the extinction of some families in the 18th century, six families (1729: Gugel, Oelhafen, Peßler, Scheurl, Thill and Waldstromer) and in 1788 another three (Peller, Praun and Woelckern) had to be granted “judicial and council capacity” not all offices and deputations could be filled.

Like the commercial councilors of most other German imperial cities, the Nuremberg patrician families gradually embraced the Protestant faith after the Reformation in 1517 , even if some hesitated at first. As early as 1516, Luther's teacher Johann von Staupitz had made an impression on well-known citizens with his sermons in Nuremberg. After the Nuremberg Religious Discussion from March 3rd to 14th, 1525, organized by the council and led by councilor Christoph Scheurl , Nuremberg officially turned to Lutheran doctrine in several council resolutions . On April 21, 1525, the council banned Catholic masses.

Knighthood

Although thirty-nine patrician families, the self-rule over some 3,000 peasant tenants had in the outlying areas, they were the knight nobility of Frankish knights circle , the area surrounding the city circle of imperial knights , the equality denied, except for the Rieter Kornburg .

When the dispute over equality, title and salutation escalated in 1654, the patriciate turned to the emperor. In the privileges of 1696 and 1697, Emperor Leopold confirmed the patrician families their old nobility and the right to accept new families. He stated that long before they went to town they had lived in a noble and knightly class, had been admitted to tournaments, had been knighted and accepted into aristocratic pens and orders of knights, and abstained from all commercial transactions (! ) and other civil trades, and the government of a populous city would be entrusted to them. The council was given the title “noble” as a corporate (as a status) and the three foremost councilors were given the title “Real Secret Council of the Emperor” since 1721, whereby they were equated in rank and title with the captains of the imperial knighthood.

However , the claims to equality and the title “noble” had to be enforced against the imperial knighthood. Several patrician families, such as the Geuder , Kreß, Welser, Tucher , Imhoff and Holzschuher , were able to achieve their matriculation with the imperial knighthood in the Franconian knight circle through the acquisition of manors in the following decades . It was only valid for the Nuremberg patriciate that a council seat in the city and membership in the free imperial knighthood could be combined in one person. In order to be able to take over an office in the knightly canton, however, patricians had to give up their citizenship, such as Johann Philipp Geuder (1597–1650), who even became director of the imperial knighthood in Franconia, Swabia and on the Rhine. However, the families capable of advising had undoubtedly achieved equality and equality with the free imperial knighthood in imperial and princely administrative services and in military service. They rose to the highest ranks in the officer corps of the Frankish Reichskreis and in the imperial army .

Through the Rieterstiftung , the city of Nuremberg became a member of the Imperial Knighthood itself in 1753, after the Rieter von Kornburg had died out, because the Rieter bequeathed the land and castle lords of Kornburg , Kalbensteinberg and Untererlbach to the Heilig-Geist-Spital and thus to the city; In this way, the respective foundation administrators came from the patriciate to the knighthood.

Nobiles Norimbergenses

The rich patricians, also known as Nobiles Norimbergenses , were clearly distinguished by their dress codes as the first class. By the adoption of the Dance Statute in 1521, the formation of a hierarchically structured society in five classes was complete. The social boundaries were precisely defined by title, clothing and living expenses and, for example, regulated by the authorities in dress codes. A fashion edict issued by the council regulated the form, quality and decoration of what the representatives of the first estate should wear in order to maintain the order of the estate.

The first estate was the oligarchical group of the patriciate, 42 families who were the only ones "capable of counseling" (for the Inner Council) and who exercised sole power in the imperial city and its rural area. The second estate was made up of the large merchants and the important families of lawyers who were represented in the Greater Council and were later also referred to as "honesty". These were often hardly inferior to the patricians in terms of wealth and economic power. The other merchants and traders of the Greater Council and the eight craftsmen of the Smaller Council made up the third estate. The small traders and craftsmen of the Greater Council belonged to the fourth estate. B. also the craftsman Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) to be counted. All other citizens of the city made up the fifth estate. The first to fourth estate only comprised around 400–450 people out of about 50,000 inhabitants of Nuremberg in the 16th century.

The estates located below the patriciate contributed not insignificantly to the city's wealth. The years around the turn of the century between 1470 and 1530 are considered the Golden Age . The city traded with almost all parts of the then known world, and its merchants had trading establishments in many cities. The saying was about: "Nuremberg trinkets go through all the country". The city was also called "the realm's treasure chest". Highly artistic craftsmen such as Dürer, Veit Stoss and Adam Kraft created great works, the technical ingenuity became known as the Nuremberg joke . Patricians such as the councilors and humanists Willibald Pirckheimer , Hieronymus Holzschuher , the traveling cloth merchant and globe inventor Martin Behaim , the land keeper and technical draftsman Martin Löffelholz von Kolberg († 1533) or the caretaker and cartographer Paul Pfinzing also took part in these developments. The city's income at that time is said to have been greater than that of the entire Kingdom of Bohemia .

In the course of the 17th century, however, the patricians withdrew more and more from trading, acquired extensive estates and demonstratively cultivated the aristocratic lifestyle in their lavishly furnished mansions in the area around the imperial city, as practiced by the imperial knights and the knighthood of the surrounding principalities. Her sons took on foreign court and war services, others turned to the Frankish imperial knighthood, giving up their civil rights after they had acquired manors with the appropriate status. After all, 39 patrician families owned around 3,000 peasant people in the Nuremberg region in the 17th century. They left the commercial activities to the lower classes. Above all, however, they neglected the economic interests of the city entrusted to them and, with their ostentatiousness, contributed significantly to the ever increasing debt of Nuremberg.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the previous trade flows from the Levant , via Italy and the Alps to the southern German imperial cities, shifted to the north. A few generations after the Nuremberg residents, the patricians of the Dutch port cities now experienced their golden age. The precious metals from America also led to a money and sales crisis. Spain, France and the Netherlands declared national bankruptcy several times in the course of their wars among themselves . The Welsers sold their Nuremberg branch in 1610 and their Augsburg trading company was insolvent in 1614. The last councilors still active in long-distance trading , the Tucher and Imhoff , who were particularly involved in the import of saffron , and the Pfinzing , finally withdrew to their estates.

The Thirty Years' War brought many Protestant exiles from the Habsburg hereditary lands (Austria, Bohemia and Hungary) to the city, including numerous noble families who had lost their home through sale or expropriation. Sometimes they also married the Nuremberg council families. From 1637, under the Khevenhüller family and their heirs, especially by Countess Margaretha Susanna von Polheim from 1693 to 1721, the Oberbürg Castle in Laufamholz became the social center of the Austrian religious refugees.

In the Baroque period that followed , the ruling church princes in the surrounding abbey residences such as Würzburg, Bamberg and Mainz displayed enormous splendor with church and palace buildings and lavish festivities. The pen nobility, who made good money in their service, also built a number of magnificent castles. For reasons of prestige, the Nuremberg patricians also spent the money (which was no longer so plentiful) with full hands. These grievances became known for the first time in 1696 through the foremost slogan Paul Albrecht Rieter von Kornburg . He tried to counteract these mistakes, to reorganize the finances and to reduce the national debt , but did not get through to the council. In protest he resigned his office, gave up his citizenship, joined the imperial knighthood and retired to Kornburg.

End of the patriciate

After the end of the imperial city period , the city council was ousted. On October 28, 1808, the Bavarian king dissolved the previous patrician council and all institutions of the city government and thus ended the Reichsstäditsche constitution. The economic bourgeoisie, which had hitherto been largely excluded from the city government due to the patrician rule, sympathized with the new Bavarian rule, from which it promised political participation and trade advantages as a result of its inclusion in the larger Bavarian economic area. The Kingdom of Bavaria recognized the equality of the old patriciate with the Bavarian nobility. Of the twenty-five patrician families still in existence at the time of transition to Bavaria, the old families - listed in the dance statute of 1521 - were enrolled in the baron class in 1813 . In contrast, the families that were co-opted only in the course of the 18th century were only accepted into the class of simple nobles.

The Nuremberg patricians had acquired numerous rural manors in the surrounding area since the late Middle Ages . Since these possessions were mostly sold again soon, some families had switched to bringing them into family foundations ( called “ Vorickung ” in Nuremberg ), which were mostly administered by the family elders and, when the family died out, were taken over by administrators from related sexes. Bavaria abolished the family foundations in 1808, which led to numerous sales. Later, however, he managed the remaining foundation possession in the form of Fideikommiss continue. These in turn were abolished in 1919. Once again, some foundations managed to survive in private law to this day. The well-deserved citizen, merchant and patron of the arts Paul Wolfgang Merkel , who bought up numerous art treasures during this time, also resorted to the legacy institute of the family foundation in order to preserve his estate, which today forms the basis of the Germanic National Museum.

After the transfer to Bavaria, the interests of the patricians were represented by the Selekt des Nürnberger Patriziats founded by them in 1799 , a corporation that still exists today as a private association of former patrician families. Previously, such a patrician society , as it had existed in other cities since the Middle Ages, was not necessary due to the factual sole rule of the Nuremberg patricians in the Inner Council . Initially, the Selekt was concerned with the concerns of the patrician family foundations vis-à-vis an imperial sub-delegation commission, which was supposed to review certain reform projects that had been implemented by the merchants and market managers since 1785. After the transfer to Bavaria, the patricians were concerned with preserving their status, with the capital that the patrician families and their foundations had lent to the heavily indebted city, with their extensive property, including sovereign rights and jurisdiction, and with preventing possible disadvantages in the Introduction of new tax rates. Selekt also intervened against the provisions of the Bavarian Fideikommissedikt of 1808 and represented the interests of the family foundations ( advances ).

On October 1, 1848, a law came into force with which all special rights of former landlords, including the Nuremberg patricians, from imperial times were repealed. Above all, this included the right to maintain their own so-called “ patrimonial courts ” with which the landlords could judge their subjects independently within the framework of the lower jurisdiction. The previous manorial ties with the peasants in the area were dissolved and the peasants were given the opportunity to replace the basic burdens with state support, a process that lasted until the inflationary period of the 20th century.

After the end of the patrician council rule, only one representative of the patriciate was first mayor , Otto Stromer von Reichenbach from 1867 to 1891.

Neunhof Castle , a patrician country estate from around 1500

Pellerschloss , a pond house from the 16th century

Pfinzingschloss in Feucht, a typical patrician seat from 1568

Kugelhammer Castle , a hammer man's seat around 1600

Patrician families

Families still thriving

Migrated

| Surname | First mention | In the council from: | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosch also: Posch |

1467 | 1536 | In the council until 1678 | Wolfgang II Bosch (1500–1558), educator of Duke Albrecht of Bavaria, Chancellor of the Straubing Rent Office. | ||

| Eyb - Pilgram of Eyb | 1165 | Members of the Frankish nobility | ||||

|

Hegner von Altenweiher Hegner von Altweyer and Moos Noble and Knights from Högen (Högn) Hegener, Hegnein, Heegn |

1385 | 1441-1459 | about 1600 emigrated to the Upper Palatinate to Bohemia ( Kostrzan , Kosterschan | Ulman Hegner, Mayor of Nuremberg (1441–1459) | ||

| Langmann (patrician) | 1352 | In the council until 1369; † 1381 | Cunz Langmann, Councilor Adelheid Langmann , mystic |

|||

|

Münzmeister (patrician) Haller called Münzmeister |

1418 | in the council until 1423, emigrated | ||||

|

Rehlinger (patrician) also: Rehlingen, Rehling |

1302 | 1468-1475 | Mentioned in 1302 in Augsburg, 1475 emigrated to Augsburg see also: Rehling |

|||

| Wolf of Wolfsthal | 1469 | 1499 | 1500 | emigrated in the council until 1504, knighted by Maximilian I around 1605 , from 1707 imperial count; † 1717 |

||

Extinguished

| Surname | First mention | In the council from: | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ammon (patrician) Ammann |

1357 | † 1483 | ||||

| Behaim from Schwarzbach to Kirchensittenbach | 1285 | 1319 | 1681 | † 1942 | ||

| Derrer von Unterbürg | 1319 | 1355 | † 1706 | |||

| Kingfisher (patrician) | 1296 | 1332 | † 1627 | |||

| Esler (patrician) | 1274 | †? | Stifter-Predella on the Katharinen Altar St. Sebald | |||

| Flexdorfer (patrician) | 1305 | 1380 | † 1449 | |||

| Feeder (patrician) | 1304 | 1501 | † 1586 | |||

| Geuschmid (patrician) | 1270 | 1347 | †? | |||

| Grabner (patrician) | †? | |||||

| Grazer (patrician) | 1311 | 1395 | † 1470 | |||

| Groland of Oedenberg | 1305 | 1346 | † 1720 | |||

| Large (patrician) | 1274 | 1319 | † 1589 | Konrad Groß | ||

|

Haid (patrician) Heyden / Haiden / Heiden |

1305 | 1357 | † 17th century | |||

| Hirschvogel (patrician) | 1380 | 1450 | † 1550 | |||

| Chamberlain (patrician) | 1303 | 1443 | † 1741 | |||

| Katterbeck (patrician) | 1283 | 1318 | † 1395 | |||

| Kestel (patrician) | 1355 | † 1355 | ||||

| Koler from Neunhof | 1246 | 1319 | † 1688 | |||

| Herbs (patrician) | 1352 | In the council until 1369; † 1450 | ||||

| Küdorfer | 1236 | 1318 | In the council until 1369; † 1598 from 1400 in the Frankish nobility |

|||

|

Lemmel (patrician) also: Lemlein, Lemblein |

1249 | 1447 | In the council until 1473; † 1513 (Nuremberg main line) | 3 foundation pictures in St. Sebald (Annunciation, Crowning of Thorns, Flagellation) | ||

|

Maurer (patrician) also: Meurl |

1249 | 1342 | † around the 16th century | Gravestone Herman Maurer at the Sebalduskirche | ||

| Meichsner (patrician) | 1396 | 1453 | † 17th century | |||

| Mendel (patrician) | 1305 | 1354 | † 1631 | |||

| Mentelein (patrician) | in the council until 1344; † 1361 (?) | |||||

|

Muffle from Eschenau Muffle from Ermreuth |

1286 | 1318 | † 1784 | |||

| Nadler (patrician) | 1347 | in the council 1347 and 1352; † 1360 | ||||

| Neumarkter (patrician) | 1259 | 1332 | † 1361 | |||

| Beneficial from Sündersbühl | 1272 | 1319 | † 1747 | |||

| Ortlieb (patrician) | 1260 | 1332 | In the council until 1442; † 1478 | |||

| Paumgartner from Holnstein and Grünsberg | 1255 | 1396 | † 1726 | |||

| Peller from Schoppershof | 1559 | 1788 | 1585 | † 1870 | ||

| Peßler (patrician) | 1427 | 1729 | † 1786 | |||

| Pfinzing von Henfenfeld | 1233 | 1274 | † 1764 | |||

| Pirckheimer (patrician) | 1358 | 1386 | † 1530 | Willibald Pirckheimer (1470–1530) famous humanist and friend of Albrecht Dürer | ||

| Pömer von Diepoltsdorf | 1286 | 1395 | 1697 | † 1814 | ||

| Priest (patrician) | 1358 | 1455 | † around 1500 | Franz Prünsterer became councilor of the Hanseatic city of Lübeck in 1619 | ||

| Puck (patrician) | 1344 | only 1344 in the council; † 1427 | ||||

|

Reich (patrician) also: Reichel |

1372 | 1447 | † 1578 | |||

| Rieter von Kornburg and Kalbensteinberg | 1361 | 1437 | 1447 | † 1753 | ||

| The hustle and bustle of Zant and Lonnerstadt | 1281 | 1402 | † 1807 | |||

| Sachs (patrician) | 1360 | in the council until 1372; † 1500 (approx.) | ||||

| Key fields of Kirchensittenbach | 1382 | 1536 | † 1709 | |||

| Schmugenhofer (patrician) | 1291 | in the council until 1378; † 1469 | ||||

| Schopper (patrician) | 1267 | 1319 | † 16th century or emigrated | |||

|

Schürstab (patrician) Schürstab von Oberndorf |

1299 | 1355 | † 1743 | |||

|

Schütz (patrician) Schütz von Hagenbach |

1404 | only 1404 and 1405 in the council, then left; † 1540 1310–1540 Hagenbach Manor. | ||||

| Seibold (patrician) | 1352 | only 1352 in the council; † 1369 (approx.) | ||||

| Starck from Röckenhof | 1387 | 1453 | † 1715 | |||

| Tetzel from Kirchensittenbach | 1326 | 1343 | † 1736 | |||

| Stone (patrician) | 1291 | in the council until 1365; † 1395 (Nuremberg Line) | ||||

| Steinlinger (patrician) , Steinling | 1397 | in the council until 1455; † in Nuremberg 1477; † 1984 | ||||

| Devil (patrician) | 1233 | ? | in the council until 1441; † 1451 | |||

|

Thill (patrician) Hack von Suhl |

1422 | 1729 | † 1771 | |||

|

Toppler (patrician) Topler |

1408 | 1475 | † 1687 | Heinrich Toppler (in Rothenburg). Toppler epitaph on the St. Peters altar in the Sebalduskirche | ||

| Valzner (patrician) | 1401 | 1403 | in the council until 1418; † 1423 | |||

|

Viehel (patrician) also: Pecus |

1285 | 1318 | †? | |||

| Vanguard (patrician) | 1243 | 1319 | † 1515 | |||

| Wagner (patrician) | †? | |||||

| Waldstromer from Reichelsdorf | 1223 | 1729 | 1551 | † 1844 | ||

| Weigel (patrician) | 1285 | 1332 | † 1430 | |||

| Woelckern (patrician) | 1530 | 1788 | 1728 | † 1905 | ||

| Zenner (patrician) | 1377 | in the Council 1377 and 1379, †? | ||||

| Zingel (patrician) | 1367 | 1435 | † 1539 | |||

| Zollner from the fire | 1340 | 1402 | † 1776 | |||

The second stand

In the class structure of the imperial city of Nuremberg, a distinction was made between the first class, the patriciate, and the second class, designated as honorable , whose members also had jurisdiction in individual cases . The term “herable” originally referred to both the advisable families, later attributable to the patriciate, their members and also the group of families from which the patriciate was recruited up to the 16th century and in nine cases in the 18th century and with whom they went through Marriage. In the 16./17. In the 19th century, the patrician class was designated as “erbar” until it was granted the right to call itself “noble” in 1697.

Since the final formation of the Nuremberg class structure, the term “sexes capable of justice” has been understood to mean that small group of families that had long belonged to the patriciate of other cities of similar rank and were already provided with imperial coats of arms or letters of nobility. In the late 16th century it was only the Oelhafen and the Scheurl, in the 17th and 18th. Several others were added in the 19th century. The families capable of being judged belonged, like the families of honor, to the second class in Nuremberg society, they could occupy offices that could otherwise only be obtained through councilors, they were denied access to the Inner Council.

Due to the extinction of council families, some "families of respectability" and families capable of being judged managed to be co-opted into the patriciate.

Honorable families

| Surname | First mention | Honorable from: | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ditl | †? | |||||

| Advocate | 1310 | 1495 | 1625 | †? | Dürer created two portraits of Fürleger ladies. Gottfried Fürleger was the last proven representative of the sex (* 1702, †?) | |

| Gundelfinger | 1350 | Fled in 1550 due to excessive indebtedness | ||||

| Half wax half wax |

†? | |||||

| Hero (called Hagelsheimer) | 1357 | † 1682 named after Hagelsheim Castle an der Tauber |

||||

| Chamberlain | †? | |||||

| Ketzel (also: Kötzel) | 1438 | Immigrated from Augsburg to Nuremberg in 1422/35; † 1588 | Heinrich Ketzell's gravestone at the Sebalduskirche | |||

| Koburger / Koberger | †? | Anton Koberger | ||||

| Köler | †? | |||||

| Kötzler | 1298 | † 1674 | ||||

| Krell | †? Cloth merchant, mining company |

|||||

| Letscher | †? | |||||

| Lochaim | 1373 | † 1546 (?) | Wolflein von Lochamer (Lochaim), around 1500, owner of the Lochamer songbook ; this collection was named after him | |||

| Melber | †? | |||||

| Ortel | † 1666 | |||||

| Ploben also: Plob von Ploben Plauen |

1451 | † 1619 | ||||

| Pucher | †? | |||||

| Romans | †? | |||||

| Schedel | † 1571 | Hartmann Schedel | ||||

| Schlaudersbach | 1495 | † 17th century | ||||

| Sneak | †? | |||||

| Schmidmeyer from Schwarzenbruck | 1380 | † 1707 | Coat of arms window in the Lorenz Church | |||

| Stupid | 1342 | Emigrated to Ulm in 1552 | ||||

| Stockamer | †? | |||||

| Trainer | †? | |||||

| Voit from Wendelstein | † 1718 | |||||

Jurisdictional families

| Surname | First mention | Jurisdiction from: | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietherr von Anwanden | 1431 | 1730 | 1813 | † 1819 | ||

| Furtenbach on Reichenschwand | 1371 | 1768 | 1813 | † 1957 | ||

| Gammersfelder from Solar | 1466 | 1730 | 1466 | † 1740 | ||

| Petz from Lichtenhof | 1450 | 1730 | 1813 | |||

| Viatis | 1538 | 1730 | 1818 | † 1834 | Bartholomew Viatis | |

Merchant families

Some families did not succeed in getting into the inner circle of the imperial city, despite their high reputation, large fortunes and family ties to patrician families; they nevertheless made a significant contribution to the fame and prosperity of Nuremberg and are mentioned for this reason.

| Surname | First mention | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landau | 14th Century | † 1515 Landauersches Twelve Brothers House |

||||

More noble families from Nuremberg

| Surname | First mention | in Nuremberg from: | Title since: | Remarks | Personalities | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilherr von Thumenberg | 1423 | 1531 | 1600 | † 1707 first Nuremberg line († 1758 second Nuremberg line) |

Johann Michael Dilherr ( Henneberg line of Dilherr) |

|

| Gründlach | 1140 | 1140 | ? | † 1314/15 Nuremberg Line † 1464 Berg-Hertingsberger Line |

Leopold I of Gründlach | |

| Winkler von Mohrenfels | 1156 | ? | ||||

Coat of arms gallery

Coat of arms window in the Lorenz Church

See also

- Dance statute

- History of the city of Nuremberg

- Castles, palaces and mansions in the city of Nuremberg

- List of Frankish knight families for lines of patrician families in the landed gentry

- Augsburg patrician families

literature

- Julie Meyer: The emergence of the patriciate in Nuremberg. In: Communications from the Association for the History of the City of Nuremberg. (MVGN), Vol. 27, 1928, pp. 1-96. ( online )

- Gunther Friedrich: Bibliography on the patriciate of the imperial city of Nuremberg . (= Nuremberg research. Volume 27). Association for the History of the City of Nuremberg . Edelmann, Nuremberg 1994, ISBN 3-87191-203-4 .

- Book review by Peter Zahn, in: Mitteilungen des Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg. Volume 82, 1995, pp. 353-355, (online)

- Eugen Kusch: Nuremberg. City life image. 5th edition. with a new chapter "1945–1989" by Christian Köster. Verlag Nürnberger Presse Druckhaus Nürnberg, Nürnberg 1989, ISBN 3-920701-79-8 .

- Christoph von Imhoff (Hrsg.): Famous Nuremberg from nine centuries. 2nd Edition. Hofmann, Nuremberg 1989, ISBN 3-87191-088-0 . (New edition: Edelmann Buchhandlung, 2000)

-

Michael Diefenbacher , Rudolf Endres (Hrsg.): Stadtlexikon Nürnberg . 2nd, improved edition. W. Tümmels Verlag, Nuremberg 2000, ISBN 3-921590-69-8 ( online ).

- Walter Bauernfeind: The old ones . S. 62 .

- Rudolf Endres : patriciate . S. 808 .

- Family register of Johann Gottfried Biedermann

- Johannes Müllner: The annals of the imperial city of Nuremberg from 1623. Part II: From 1351–1469 . Nuremberg 1972, pp. 157-170.

- Chronological list of those named in the Grand Council of the City of Nuremberg (1560–1670) . 17th century manuscript, (digitized version)

- Michael Diefenbacher: The aristocratic landscape - castles, palaces, mansions , in: Wolfgang Wüst (Hrsg.): Bavaria's Adel - micro- and macrocosm of aristocratic forms of life. Papers at the international and interdisciplinary conference. Banz Monastery, Bad Staffelstein, 26.-29. May 2016 , Frankfurt am Main, New York, Bern a. a. (Peter Lang Verlag) 2017, pp. 163–187. ISBN 978-3-631-73453-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gender towers on historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de, accessed on July 11, 2020

- ^ NDB (New German Biography), Vol. 24, p. 663

- ↑ Nürnberger Patricians , by Michael Diefenbacher, in: www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de

- ^ Technological illuminated manuscript by the Nuremberg patrician Martin Löffelholz (1505) in Cracow

- ^ Spoonwood Codex online

- ^ Friedrich Nicolai: Some news from Nuremberg. In: Berlin monthly journal. 1/1783, p. 89.

- ↑ Rudolf Johann Helmers: Renewed and increased Siebmacher Wappenbuch. Nuremberg 1695–1701.

- ^ Johann Ferdinand Roth: History of the Nuremberg trade. Vol. I & II, Leipzig 1800-1801.

- ^ Peter Fleischmann, Manfred H. Grieb (eds.); Johann Ferdinand Roth: The directory of all named of the greater council to Nuremberg from the year 1802. 2002, ISBN 3-89557-155-5 .

- ^ Peter Fleischmann, Manfred H. Grieb (eds.); Johann Ferdinand Roth: The directory of all named of the greater council to Nuremberg from the year 1802. 2002, ISBN 3-89557-155-5 .

- ^ Hans Joachim Schmid: The Schlüsselberger, Förnberger and Bosch. BFFK 37 (2014)

- ↑ Mention of Wolf von Wolfsthal

- ↑ Seal of Lemmel

- ↑ a b History of Oberndorf ( Memento from April 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ History of Hagenbach ( Memento from September 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Organ of the Germanisches Museum: Anzeiger für Kunde der Deutschen Vorzeit . No. February 2 , 1855.

- ↑ Christoph von Ploben

- ↑ Mention of the Gammerfelder in Solar ( Memento from May 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Festschrift of the Voluntary Fire Brigade Solar-Grauwinkl: Chronicle Solar Grauwinkl Auhof, Hilpoltstein 2002. Authors: Willi Stengl, Anton Strobl, Irmgard Prommersberger