Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness

Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness , published in German under the title Fall in die Nacht: The Story of a Depression , is an autobiographical work by the American writer William Styron (1925-2006). Styron describes a phase of his life in which he suffered from suicidal depression .

It first appeared in Vanity Fair magazine in December 1989 ; for this contribution, Styron was awarded the National Magazine Award for Best Essay of the Year in 1990. In 1990 Darkness Visible appeared in a somewhat expanded form as a book, sold millions of copies and was translated into more than twenty languages. Not only has the text become a modern classic in American literature , but it is also more widely cited in psychiatric literature and used in psychotherapeutic training and practice.

"Van Gogh's manic circling stars are indications of the artist's fall into madness and self-extinction," says Styron.

content

Styron's report covers a period of about half a year. It began in the summer of 1985 when Styron was in Paris to receive the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca . He had noticed the first signs of depression months before, but repressed or denied it, but now his mental state is deteriorating rapidly. When his taxi happened to drive past the hotel where he had spent his first night in Paris decades earlier, he suddenly felt sure of death, his thoughts also revolve around his friend Romain Gary , who had committed suicide in Paris in 1980, just like his wife Jean Seberg a year earlier . He still manages the acceptance speech at the award ceremony, but at the evening dinner with the patron Simone Del Duca and several members of the Académie française , he not only loses the check for the prize money, but also completely self-control: “I had no appetite the great plateau de fruits de mer that was presented to me, I couldn't even bring myself to laugh, and finally I completely lost the ability to speak. At this stage the grim inwardness of the pain caused immense disturbance, which prevented me from producing words other than a hoarse murmur; I noticed how my eyes glazed over, how I only uttered single syllables, and I also noticed how my French friends were awkwardly aware of my condition. "

After his return to New England, he went to a psychiatrist for treatment, but despite or perhaps because of the prescribed psychotropic drugs, his mind became more and more dark, the thought of suicide soon never left him: he looked at "the rafters on the floor (and outside a maple or two) to hang me up; the garage a place to breathe carbon monoxide there; the bathtub a vessel into which the blood flowing from my opened arteries ran. The kitchen knives in the various drawers only had one function for me. Heart attack death seemed particularly welcome, as it would have freed me from responsibility. I had also flirted with the idea of deliberately contracting pneumonia - a long, chilling walk in shirt sleeves through the rain-soaked forest. ”He failed several times when trying to write a worthy farewell letter. When, one evening in December, he actually begins to take precautions for his suicide - he destroys his notebooks, which posterity is not supposed to see -, when Brahms' alto rhapsody suddenly echoes from the television, his fatal predicament is revealed to him deliberately. With his “last spark of health” he wakes his wife and lets himself be admitted to the hospital, where he finally finds peace and the long process of his healing begins.

In addition, Styron ponders in numerous excursions about the nature of depression, its various names, manifestations and its representation in literary and art history. In retrospect, he finds many indications in his life story and his literary work that the disease had been announced a long time ago. As the reason for his pathological disposition - in accordance with a corresponding psychodynamic explanation - he identifies the "imperfect grief work" after the traumatic early death of his mother, as acute trigger his quite abrupt withdrawal from alcohol in June 1985 as well as his medication Halcion .

Emergence

In the first two years after his suicide attempt, Styron contemplated processing his experiences in fictional form. In accordance with his conviction that the repressed confrontation with his mother's death was the cause of his depression, he first devoted himself to this aspect of his suffering. The strongly autobiographical short story A Tidewater Morning (published 1987) emerged from this grief work . He then started a novel that was supposed to reflect the course of his illness, but gave up this venture after a few months. He made the decision to make his personal experiences with depression public in non-fictionalized form in 1988, also in response to the public reaction to the suicide of the Italian writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi in April 1987. In November 1988, Styron read in New York Times reported on a symposium on the life and work of Levi held at New York University . The newspaper reported that many of those present had expressed their incomprehension that someone who had survived Auschwitz should allow themselves to be driven into such desperation by comparatively banal everyday worries, some even saw Levi's work discredited, the will to live in the face of the had addressed massive dying. Styron was so outraged by the suggestion that Levi's suicide was a character flaw or an expression of lack of moral steadfastness that he began to write a reply. His article, titled Primo Levi Need Not Have Died , appeared on December 19, also in the New York Times . In it, he castigated general ignorance about the nature of depression and cited his own healing as evidence that in many cases it could be cured with medical help.

After the publication, he received an unexpected number of letters thanking him for his contribution. The enormous popularity strengthened him in his will to promote public education on the subject. In May 1989 he read a first draft of Darkness Visible at a symposium of the Department of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University and shortly afterwards attended the first meeting of the newly formed American Suicide Foundation in New York. There the publicist Tina Brown became aware of him. She convinced him to revise his lecture and publish it as an essay in the December issue of Vanity Fair . The response was again enormous: Over the next few weeks, Styron received thousands of letters to the editor, from which he learned, among other things, that his essay had spread like a chain letter and had reached not a few of his readers in photocopies from fourth or fifth hand. In view of the great demand, but also in order to make the work accessible in a more permanent form, Styron decided to publish the text, which is only around 15,000 words long, in book form and to add some passages that he had to delete from the magazine print for reasons of space , especially those about the events in Paris, which are the introduction in the book version. In August 1990, the complete version, edited by Styron's long-time editor Robert Loomis , was published as a book by Random House .

Themes and motifs

The limits of language

Styron's concern is to explain to the general public what depression looks like for those affected. As he himself admits, this is a paradoxical endeavor:

“Depression is a disturbance of the emotional life that is so mysteriously painful and, from the way in which it experiences the self - the mediating intellect - so elusive that it is almost impossible to describe. Therefore it remains almost incomprehensible to those who have not experienced it in its extreme form [...] "

Even William James , one of the founders of modern psychology and himself affected by severe depression, finally gave up the search for a suitable image, in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) he wrote, man have to imagine "a kind of psychological neuralgia as it is completely unknown in normal life". The difficulty of the depressive in verbalizing his or her inner experience is a fundamental problem in clinical practice, and it often makes a precise diagnosis and the choice of an appropriate therapy difficult. The fact that Styron's text apparently managed at least an approximation of this inexpressible and that numerous readers recognized their own experiences in it makes it interesting for psychology and psychiatry; Much of the work on the linguistic design of Darkness Visible was therefore written by representatives of these subjects. Her research purpose is, on the one hand, to improve communication between patient and therapist in talk therapy , and, on the other, to promote public relations for health education of the population.

In a more general sense the limits of language are a problem of epistemology , but in a very direct sense it is also a problem of literature. Styron himself prominently addressed them in another context: in his 1979 novel Sophie's Choice about the Holocaust in Poland, which was very controversial at the time , he repeatedly asks whether there is an appropriate language for the horrors of the concentration camps could; Styron's theoretical reference text is George Steiner's Language and Silence (1967, German "Language and Silence. Essays on Language, Literature and the Inhuman"). As in Darkness Visible , the attempt to describe the indescribable, the “hell”, presents itself to him as a moral imperative; In 2002 he said in his acceptance speech for the Witness to Justice Award from the Foundation for the Jewish Center in Auschwitz : “It would be a serious neglect of duty not to break the imposed silence and not to preserve the knowledge of this hell for future generations, like that imperfect the representation may be. "

Symptoms and imagery

The focus of the analyzes written by psychologists in particular are the numerous metaphors with which Darkness Visible makes the symptoms of suffering clear. The metaphor as a form of improper speaking, which is particularly open to meaning and in need of interpretation, differs fundamentally from the medical nomenclature, which aims at clarity, but the term "depression" is also based on a metaphor (linguistically speaking, it is a catachresis ). It was only shaped in the 20th century by the Swiss psychiatrist Adolf Meyer , who teaches in the USA - according to Styron, a very unfortunate choice and possibly due to Meyer's lack of feeling for the subtleties of the English language. “Depression,” which in English also means something as banal as a depression in the ground, seems completely inappropriate to him, a absurd “cheap phrase”. For Styron, this is not just a question of aesthetics, but with his coining of the term Meyer has permanently falsified the common ideas about this ailment. The older term melancholy (Greek μελαγ-χολία, so Schwarzgalligkeit ') still appropriate, also a "brutal, old-fashioned word" appears Styron as madness (English madness ,), because it was so Styron, "be no doubt that Depression in its worst form is nothing more than madness. ”But the best thing would be a new,“ really concise term. ”If the word wasn't already used, he himself would advocate“ brainstorm ”, because depression is most likely to resemble“ one full-blown raging hurricane in the brain. "He takes up weather metaphors again and again, often in connection with light or darkness:" It is a hurricane, but one made of darkness. The slowed reactions soon show up, almost paralysis, the psychic energy is almost completely throttled. In the end, the body is also affected, feels weakened, drained. ”Elsewhere, Styron writes that he“ felt a feeling in his head that was close to pain and yet indescribably different [...] For me, the pain is connected to Most likely drowning or suffocating - but even these comparisons are imprecise. "He feels a pain that cannot be assigned to a place like physical ailments:

“I realized that in a mysterious way that had nothing to do with everyday experience, the drizzle of horror that causes depression can take the form of physical pain. However, it is not an immediately identifiable pain such as a broken bone. It would be more accurate to say that through a malicious trick played by the psyche living in the sick brain, despair is like the diabolical discomfort one feels when one is locked in a terribly overheated room. And because there is no soothing breath of air into the cauldron, because there is no way out of this suffocating prison, it is only natural when the victim begins to think incessantly about the unconsciousness. "

Styron's confusion arises from the traditional distinction between physical and psychological pain, which is increasingly being questioned in recent neuroscience . Even more times he compares his helplessness with that of a suffocating or drowning person, elsewhere he writes that “the disturbance gradually took over my organism completely, I also noticed that my mind was like one of those outdated telephone systems in small places, that are inundated by a flood: One by one, the networks went under, causing some bodily and almost all instinctive and intellectual functions to slowly shut down. ”The idea that it is an alien, hostile force, the bodies and Soul overwhelmed, the Israeli psychiatrist Israel Orbach identified as the most prominent characteristic of the descriptions of depression at Styron.

Like Orbach a year earlier, a group of American psychologists subjected Darkness Visible to an empirical content analysis in 2004 . The researchers counted a total of 1,383 metaphors on 84 pages, more than half of which were used to describe depression. They interpreted Styron's metaphor system as “consistent”, that is, coherent and free of contradictions, and as “externally valid” in terms of the theory of social representation . In other words, Styron does not find completely new, idiosyncratic or alienating expressions (a strategy peculiar to poetry in particular), but uses a generally understandable language and, above all, images that have long been used in Western culture to describe "dark" states of mind , so stereotypes . This finding is double-edged: On the one hand, it explains why Darkness Visible appealed to so many readers, but on the other hand, it also explains the scathing review by Al Alvarez , who in 1972 presented The Savage God, a now classic study on suicide and in how Styron described his own suicide attempt in Darkness Visible . In the Sunday Times in 1991, Alvarez complained that Styron's book was little more than an accumulation of platitudes and clichés .

The depression in literature, art and philosophy

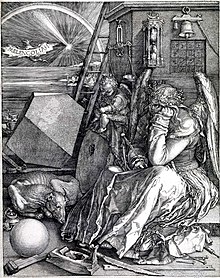

References to the history of literature run through the book from the first to the last sentence, just as the subject of depression runs through literary and art history like a “red thread of suffering” - Styron recognizes attempts to express it in the choirs of Sophocles and Aeschylus , in Hamlet's famous monologue, in the poetry of John Donne and Gerard Manley Hopkins , and in the novels of Nathaniel Hawthorne , Fyodor Dostoyevsky , Joseph Conrad, and Virginia Woolf . Suffering shaped the music of Schumann , Mahler , Beethoven and the “solemn cantatas” of Bach, as well as many engravings by Albrecht Dürer , the paintings by Vincent van Gogh and the films by Ingmar Bergman (he named in particular Wie in einer Spiegel ). Elsewhere, the autumn light reminds him of Emily Dickinson's famous “ slant of light ”, “which reminded her of her own death, of cold extinction,” a little later Baudelaire's diary entry of January 23, 1862, does not want him get out of my head, "I felt a wind blow over me from the wings of nonsense." As Kathlyn Conway notes, Styron's choice is downright canonical; It is astonishing how many writers refer to the same few reference texts in describing their anguish, especially the metaphysical poets of the 17th century (including John Donne), the book of Job and Dante's Divine Comedy . In the book edition, Styron put a quote from the Book of Job (3.25–26 LUT ) in front of his report as the motto ("For what I feared has come upon me, and what I dreaded struck me. I had no peace, no rest, no rest, there came another hardship ”), he closes the work with a quote from Dante. The German translation by Willi Winkler does not reproduce the oxymoron darkness visible , "visible darkness", which Styron chose as the title. It is a quote from the description of hell in the first book of John Milton's blank verse epic Paradise Lost (1667, German " Paradise Lost "):

|

|

Styron admits that he is certainly not the first to describe the “ravages of melancholy” with the famous opening lines of the Inferno (i.e. the first part of the Divine Comedy ), but for him it is still “the most impressive metaphor that this one is the most faithful expression of infinite torment ": Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura / Ché la diritta via era smarrita (" Halfway through human life / I found myself in a dark forest / Because of the right Turned away from me ”). But this "gloomy premonition" all too often overshadows the hope of the verse with which Dante ends his journey to hell and with which Styron also ends his book: E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle ("Then we stepped out and saw the stars again" ).

An indirect anticipation of Dante's allegorical image of the dark forest from which one steps back into the light can be found in Darkness Visible at the point that marks the dramatic turning point of the plot and heralds the beginning of his healing for Styron personally. After only pondering about it so far, Styron actually begins to prepare for his suicide one December evening. When he destroys his notebooks, which posterity should not see, the television is on in the background. In the film shown (Styron's biographer James W. West identifies him as The Bostonians ) at some point, “an alto voice, a suddenly rising passage from Brahms'› Alto Rhapsody ‹.” This song, which his mother had sung many times, was able to make it into Styron to arouse sensations again, and with the "last spark of health" he grasped the "terrible dimensions" of his situation, woke his wife and had himself taken to the hospital. Brahms ' Rhapsody for an Alto Part (1869) is a setting of the Harzreise im Winter (1777/1789), one of Goethe's most enigmatic and melancholy poems . The lyrical self regrets a gloomy, lonely wanderer:

“But apart from that, who is it?

His path is lost in the bushes, The bushes collapse

behind him

,

The grass rises again,

The desolation devours him.

Oh, who heals the pain of Him whose

balm was turned into poison?

Which misanthropy

drank from the wealth of love!

First despised, now a despiser,

he secretly feeds on

his own worth

in insufficient selfishness. "

Goethe's poem ends with further desolate views of the lonely traveler, but Brahms ends his rhapsody after the third stanza with the intercession "Refresh his heart!" Repeated several times by the male choir; so it is probably the passage of which Styron writes that it "dug like a dagger" into his heart.

By appealing to Dante and Milton, Styron gives the depression a meaning in theological terms: it presents itself to him - like Auschwitz in Sophie's Choice - as hell , as a state of condemnation , and he describes his long but healing hospital stay as "Stopover, a purgatory ". The reference to the life-saving passage in Brahms resp. Goethe lets the healing appear as redemption , elsewhere Styron describes his condition as one of godforsakenness and crucifixion . The idea of a divine grace - or a god - is alien to Styron, however, his worldview is rather shaped by the philosophy of French existentialism . His acquisition of theological terms can be understood on the one hand as a rhetorical maneuver, i.e. as a metaphor or hyperbole . For David B. Morris , however, Styron's torments in an ungodly world are even more arduous than Christian hell; While the condemnation into the realm of darkness at Milton at least serves a traditional purpose, i.e. the divine punishment of sinners, Styron can see no meaning or reason at all in his suffering. It is even more lonely: while Satan can at least enjoy the company of his devils (one third of the angelic army) in Milton's hell, with Styron the "grim inwardness of pain" means that he can no longer communicate with anyone. Another critic, on the other hand, emphasizes that Styron's work may be godless, but not pointless, after all, Darkness Visible and Sophie's Choice are declared to have arisen out of a feeling of a moral obligation to name evil .

In a longer passage, Styron is dedicated to Albert Camus , whom he names as a formative influence on his worldview and his own literary work. Especially L'Étranger (1942, German: “The Stranger”) once shook his soul to the core, reading Camus as a whole had a “cleansing” effect on his young mind and filled him with a new zest for life. For all his admiration, however, he found the gloomy monologues of the lawyer in the late work La Chute (1956, "The Case") to be very weeping - but today he is in a position to recognize that he is "suspicious as a Mann behaved in the struggle with clinical depression. ”Styron now feels a similar situation with Camus' most famous postulate, the opening sentence of Le mythe de Sisyphe (1942, Eng.“ The Myth of Sisyphus ”):“ There is only one really serious philosophical problem : suicide. ”As a young man he admired the work's defiant will to live, but was unable to understand the initial hypothesis that“ someone could only vaguely wish to commit suicide ”. In 1985, however, in Paris he suddenly became certain that he would soon “come to the conclusion that life is no longer worth living” and thus answer “the fundamental philosophical question” for himself. Now he knows that "Camus' remarks on suicide, in general his preoccupation with this topic, may be just as strongly based on a stubborn mood disorder as in his preoccupation with ethics and epistemology ," especially since their mutual friend Romain Gary told him of his depression years ago have reported.

Many personal circumstances in his life now appear to Styron in a different light and are only now being explained to him. How momentous it is that a depression can hardly be conveyed to an outsider, Styron recognizes in the retrospective memory of 1978; When Romain Gary and Jean Seberg stayed at Styron's for some time, he knew about their depressions and felt sorry for them, but he did not find them unusual, they were “abstract complaints” for him an inkling of the actual extent or nature of that pain ”. Gary's voice had the "gasping sound" of a very old man; In 1985, Styron observed that he now had "the same elderly voice" himself, weak, gasping and convulsive, "the voice of depression". Seberg committed suicide in 1979 with an overdose of tablets; Gary, two-time winner of the Prix Goncourt , "a hero of the republic, brave recipient of the Croix de guerre , diplomat, bon vivant, legendary philanderer", shot himself a year later.

Seemingly contradicting this, Styron describes his own literary work as downright clairvoyant: In three of his novels a protagonist kills himself, and when he reread them for the first time in years, Styron is shocked at how precisely he described "the landscape of the depression in his head" have. He attributes this instinct to his “unconscious, which was already agitated by mood disorders”: “So the depression when it finally caught up with me was anything but strange, not even a surprising visit; she had already knocked on my door for decades. ”A psychoanalytically trained critic remarks that Styron probably just as unconsciously and unknowingly practiced the psychotherapeutic method of writing therapy on his own .

Depression as a disease

The stigma that still clings to depression (and suicide) is based on the idea that it is ultimately an expression of personality, hence a character defect. As in his essay on Primo Levi, Styron resolutely opposes this prejudice: Depression should rather be understood as a disease, an alien power that attacks its victims against their will and can attack anyone, yes, it is “as fundamentally democratic as one Poster by Norman Rockwell "and hit" indiscriminately in every age group and race, with every religious community and class "(but more often with women than men), afflicts" tailors, ship captains, sushi chefs, ministers "alike. Although he admits that depression can have a variety of causes and its etiology has hardly been researched, it is undoubtedly a disease like cancer or diabetes, which if left untreated, often leads to death. Suicides like Primo Levi can therefore not be blamed any more than cancer sufferers. On the other hand, Styron's purely clinical view of depression contradicts the insight he has expressed himself that “the artistic type (especially the poet) is particularly susceptible to the disorder.” He leads a “sad, but also sparkling list of names” of artists, who took their own lives: " Hart Crane , Vincent van Gogh , Virginia Woolf , Arshile Gorky , Cesare Pavese , Romain Gary , Sylvia Plath , Mark Rothko , John Berryman , Jack London , Ernest Hemingway , Diane Arbus , Tadeusz Borowski , Paul Celan , Anne Sexton , Sergei Jessenin , Vladimir Mayakovsky - the list goes on. "

The classification of depression as a disease was already anchored in the diagnostic guidelines at the time and actually led to a gradual removal of the taboo; it reduces self-reproach and the suffering of those affected and above all lowers the inhibition threshold to consult a doctor in the event of illness. But the psychotherapist, with whom Styron first went into treatment, advised him that he should refrain from inpatient treatment at all costs because he would carry a stigma. Even and especially in society, the clinical view does not meet with acceptance everywhere - for example in psychoanalysis, as Freud also considered melancholy to be an expression of moral inadequacy ( Trauer und Melancholie , 1917). Conservative critic Carol Iannone dismissed Styron's "clinical" account in her scathing review of Darkness Visible for Commentary as cheap excuses. All the references to neurotransmitters, chemicals, hormones, his larmoyantly dramatized helplessness (“ Poe or Coleridge for the poor,” according to their judgment) lacked any moral dimension; Ultimately, he just shirked responsibility for his own way of life, especially his alcohol consumption, and his neurotic self-consciousness. Iannone compares Styron's attitude unfavorably with the ethos of Alcoholics Anonymous , who also understand alcoholism as a disease, but at the same time focus on their own willpower, humility and anonymity - whereas Styron makes a difference, like many other celebrities who do , hardly released from the rehab clinic, already let their fate weep on the talk shows.

In his comparison of depression and cancer, Styron adopts the argument that Susan Sontag had outlined in her 1978 essay Illness as Metaphor (Eng. "Illness as Metaphor"). Sontag opposed attempts to equate illness (especially cancer) with sickness. In the years that followed, your essay played an important role in the discussion about the AIDS epidemic, which primarily affected homosexual men and was often viewed, especially in conservative circles, as a self-inflicted result of a lack of morality; In 1989, just a few months before Darkness Visible , Sontag published the follow-up essay AIDS and Its Metaphors ( Eng . "AIDS and its metaphors"). The unexpected response to his article on Primo Levi and his depression ("something to be dealt with in secret and in shame") had shown him that he had helped "open a locked chamber that many wanted to come out of to proclaim." they too had experienced the feelings I had described ”- Styron alludes to the expression coming out of the closet , which is now also idiomatic in German as“ coming out of the closet ”for homosexuals coming out . Styron's comparison with homosexuality was most likely due to the social stigma that is inherent in homosexuality and depression, but as Abigail Cheever shows, it ultimately complicates Styron's premises, as a coming-out confirms homosexuality as a constituent part of the Personality, as a given . For Styron, on the other hand, depression presents itself as an alien that temporarily robs the self of freedom and takes control of the person , of thinking and acting. The self can be helped to regain its right through a healing process; it therefore presents itself as unchangeable, as an essence . Ultimately, it also follows from this conviction that in a certain sense it was not William Styron who transferred his hosts to Paris, and Nor was it Primo Levi "himself" who took his own life. Cheever illustrates the possible contradiction in Styron's argument in a comparison with Walker Percy , a writer who resembles Styron in many ways, especially both are equally influenced by French existentialism . Percy turned in his essay The Coming Crisis in Psychiatry in 1957 and in 1987 in his satire The Thanatos Syndrome (Eng. "The Thanatos Syndrome") against the increasing tendency to pathologize melancholy, because especially with artists a therapy comes the abandonment of an “authentic existence”, yes, a “loss of the self”.

Criticism of the view of depression, as postulated by Styron, comes not least from authors who, with Michel Foucault, reject the objective validity claim of categories such as “clinical” and in them rather an ultimately repressive exclusion of “the other” (here the other the Reason or health).

reception

The first Vanity Fair print generated a huge public reaction, earning Styron a National Magazine Award for Best Essay of the Year in 1990 . After the publication, Styron gave readings and numerous interviews on the subject of depression in the press and radio in many places for years. The media interest in him reached such an extent that he was afraid of appearing as a "guru of depression", so that he also turned down a few invitations, but out of a certain sense of duty he kept speaking up; In January 1993 he published the article Prozac Days, Halcion Nights in The Nation , in which he reported on the one hand about his life-threatening experiences with the sleeping pill Halcion , on the other hand in sharp words the pharmaceutical company Upjohn for distribution and the Food and Drug Administration for criticized the approval of this drug. The book version reached the top of the New York Times bestseller list in the non-fiction category after its publication ; He had already succeeded in doing this in 1967 with The Confessions of Nat Turner and 1979 with Sophie's Choice , but always in the fiction category, ie “beautiful literature”. For Styron's literary reputation, however, as some commentators note, the enduring success of Darkness Visible looks a bit ambiguous: While his long, dense novels are read less and less, Darkness Visible is his best-known work today. An anecdote that Christopher Hitchens describes in his autobiography Hitch-22 (2010) gives an impression of the broad impact the book had . One day he was having lunch with Styron at a rather seedy establishment in Hartford , Connecticut :

“At this dinner we were served by a pitifully depressed, pimply-faced youth with stringy hair. When he got back with Bill's credit card, he noticed that the name on it was almost like that of a famous writer. Bill didn't say anything. The boy added expressionlessly: "His name is William Styron." I left the whole thing to Bill, who held back again until the boy finally stated soberly: "In any case, the guy saved my life." Then Styron invited him to sit down take, and could credibly assure him that he was sitting at the same table as the author of Darkness Visible . A real transformation took place with the boy. He shared how he had sought and found the much needed help. "Does this happen to you often?" I asked Styron later. “Oh, all the time. The police even called me and asked if I could speak to the man who is about to jump. ""

Although some well-known American writers had written their experiences with depression before Styron, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald in his essay series The Crack-Up (1936) and Sylvia Plath in her only novel The Bell Jar (1963), Styron becomes today often viewed as the founder of the depression narrative as a literary genre . Since Darkness Visible , numerous experience reports from depression patients have appeared, which, thanks to the great demand of the American readership for "relentlessly honest" autobiographies ( tell-all ), often reach a broad readership, for example Elizabeth Wurtzel's Prozac Nation (1994, filmed in 1996), Kay Redfield Jamisons An Unquiet Mind (1995), Lewis Wolperts Malignant Sadness (1999), Andrew Solomons The Noonday Demon (2001, National Book Award winner ), Ned Vizzini's It's Kind of a Funny Story (2006) and Siri Hustvedt's The Shaking Woman or A History of My Nerves (2009). The fictionalized descriptions of the depression in the work of David Foster Wallace ( Infinite Jest , 1995, and The Depressed Person , 1999), who committed suicide in 2008, once again brought the subject into the focus of the American literary scene, should also be emphasized. Numerous commentators referred to Darkness Visible as canonical text for comparison . Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) also suggested comparisons . In this book Didion dealt with depression as the experience of grief after the death of her husband in a very similar way to Styron ; in her memoirs she mentions, probably not entirely by chance, that Dunne last read Sophie's Choice . The psychiatrist Peter D. Kramer points out two important differences: In contrast to depression, grief does not adhere to any social stigma; on the other hand, it is a very personal experience that can hardly be generalized. Depression also appeared in various forms, but at least the symptoms were uniform enough to allow an "iconic" representation. Do this by Darkness Visible ; For years he himself had advised his patients to give this book to their relatives to read, "to explain the inexplicable," and he always had a copy in stock in his practice.

Above all, critical voices complain that Darkness Visible is by no means the "ruthlessly honest" report that it claims to be. Both his wife Rose Styron and his daughter Alexandra Styron have published versions of the events of 1985 and beyond that contradict what is depicted in Darkness Visible . Styron, for example, does not mention the fact that he suffered another major depressive episode in 1988 and possibly made another suicide attempt, and he went into psychotherapeutic treatment even before his stay in Paris. According to Alexandra Styron, it is also wrong to say that her father woke his wife on that December night on his own initiative (with his "last spark of health") to look for a doctor, she remembers rather how he spent hours with disheveled hair raged loudly through the apartment, lamenting his lot and his sins and begging his family again and again as if from their senses not to hate him until the daughter whispered the word "hospital" to her mother. The discrepancy between author and narrator, between reality and representation, is problematic in Darkness Visible more than in other literary and autobiographical texts, according to Lee Zimmerman, precisely because Styron's text is also canonical in psychiatric circles and shapes the public image of the disease to this day , but paints a distorted picture of depression, or at least represents only one of its many manifestations and courses; Zimmermann, who himself suffered from depression, at least did not find himself in the text; rather, he describes his reading as "depressing". He sees Styron's reassuring affirmation that depression can be "overcome", even the seeds of stigmatization of those who do not "succeed".

literature

expenditure

- Darkness Visible . In: Vanity Fair , December 1989, pp. 212-286; this version is available online under Darkness Visible .

-

Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness. Random House, New York 1990, ISBN 0-394-58888-6 .

- New edition: Modern Library, New York 2007, ISBN 0-679-64352-4 .

-

Fall into the night. The story of a depression . From the American by Willi Winkler . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-462-02088-9 .

- New edition: Ullstein, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-550-08829-2 .

- An excerpt from Winkler's translation was published on February 22, 2011 in Spiegel Wissen magazine 1/2011 and can be read online under Fall into the Night The Story of a Depression (8 pages) .

Secondary literature

- Jeffrey Berman: Surviving Literary Suicide . University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1999. ISBN 1558491953

- Abigail Cheever: Prozac Americans: Depression, Identity, and Selfhood . In: Twentieth Century Literature 46: 3, 2000. pp. 346-368.

- Elisabeth El Refaie: Looking on the Dark and Bright Side: Creative Metaphors of Depression in Two Graphic Memoirs . In: a / b: Auto / Biography Studies 29: 1, 2014, pp. 149–174.

- Suzanne England et al .: “The Speech of the Suffering Soul”: Four Readings of William Styron's Darkness Visible . In: Psychoanalytic Social Work 13: 1, 2006. pp. 1-19. doi : 10.1300 / J032v13n01_01

- Peter Fulham: How Darkness Visible Shined a Light: Twenty-five years ago, William Styron's autobiography drew attention to the reality of depression . In: The Atlantic (online edition), December 7, 2014.

- Kerry Kidd: Styron Leaves Las Vegas: Philosophy, Alcohol and the Addictions of Experience (PDF; 70 kB) . In: Janus Head 6: 2, 2003. pp. 284-297.

- Jermaine Martinez: Rhetorical Dimensions of 20th-Century Depression Memoirs: Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar, William Styron's Darkness Visible, & Kay Redfield Jamison's An Unquiet Mind . Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2016.

- Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle”: Metaphors of Depression in Styron's Darkness Visible . In: Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23: 3, 2004. pp. 325-346. doi : 10.1521 / jscp.23.3.325.35454

- Andrew Stubbs: The Script of Death: Writing as Addiction in William Styron's Darkness Visible . In: Kenneth Gordon and Béla Szabados: Writing Addiction: Towards a Poetics of Desire and Its Others . Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina 2004. pp. 115-134. ISBN 0889771766

- Simon Thomas Walker: Spinoza, Styron, and the Ethics of Healing . In: Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 11: 2, 2016, pp. 153-160.

- Lee Zimmerman: Against Depression: Final Knowledge in Styron, Mairs, and Solomon (PDF; 291 kB) . In: Biography 30: 4, 2007. pp. 465-490.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fall in die Nacht , p. 121 (all quotations in the following after the edition in Ullstein-Verlag 2010).

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 34.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 79.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 100.

- ↑ Thornton F. Jordan: surmounting the Intolerable: Reconstructing Loss in Sophie's Choice, "A Tidewater Morning," and Darkness Visible . In: Daniel W. Ross: The Critical Response to William Styron . Greenwood Press, Westport CN 1995, pp. 257-268.

- ↑ James L. West III .: William Styron, a Life . Random House, New York 1998, pp. 447-450.

- ^ William Styron: Primo Levi Need Not Have Died (PDF; 741 kB) . In: The New York Times, December 19, 1988.

- ↑ James L. West III .: William Styron, a Life . Random House, New York 1998, pp. 451-453.

- ↑ James L. West III .: William Styron, a Life . Random House, New York 1998, p. 454.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 17.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 30–31.

- ↑ See for example: Deborah Flynn: Narratives of Melancholy: A Humanities Approach to Depression . In: Medical Humanities 36: 1, 2010, pp. 36-39. doi : 10.1136 / jmh.2009.002022

- ↑ Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle” , pp. 344-345.

- ↑ Andrew Stubbs: The Script of Death , pp. 120-121.

- ↑ Suzanne England et al .: “The Speech of the Suffering Soul” , p. 14.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 72.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 75–76.

- ^ David B. Morris: Illness and Culture in the Postmodern Age . University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles 1998, pp. 232-233.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 72.

- ^ Israel Orbach: Mental Pain and Suicide . In: Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 40: 3, 2003, pp. 191-201.

- ↑ Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle” , pp. 333-334.

- ↑ Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle” , pp. 338-343.

- ^ A. Alvarez: The Wind of the Wings of Madness. In: The Sunday Times, March 3, 1991; quoted in: Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle” , p. 338.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 69–70.

- ^ Kathlyn Conway: Illness and the Limits of Expression . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 2007. p. 91.

- ^ John Milton: Paradise Lost I.61-69. German translation after Bernhard Schuhmann (1855), in: Friedhelm Kemp and Werner von Koppenfels (eds.): English and American poetry , Volume 1: From Chaucer to Milton . CH Beck, Munich 2000. p. 441.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 99–100.

- ↑ George E. Butler: Goethe, Brahms, and William Styron's Darkness Visible . In: Notes on Contemporary Literature 39: 2, 2009. pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 104.

- ↑ Suzanne England et al .: “The Speech of the Suffering Soul” , pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Thomas J. Schoeneman et al .: “The Black Struggle” , p. 340.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 104.

- ^ David B. Morris: Postmodern Pain . In: Tobin Siebers (Ed.): Heterotopia: Postmodern Utopia and the Body Politics . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1994. pp. 150-173, here p. 167.

- ↑ Suzanne England et al .: “The Speech of the Suffering Soul” , pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 40–45.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 116–117.

- ^ Suzanne England et al .: "The Speech of the Suffering Soul" .

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 55.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 101.

- ^ Carol Iannone: Depression-as-disease . In: Commentary 90: 5, Nov. 1990, pp. 54-57.

- ↑ Fall into the Night , p. 53.

- ↑ Abigail Cheever: Prozac Americans , pp. 347-348.

- ↑ Abigail Cheever: Prozac Americans , pp. 347-348, p. 362.

- ↑ Abigail Cheever: Prozac Americans , pp. 351-358.

- ↑ Lee Zimmerman: Against Depression , p. 468.

- ↑ James L. West III .: William Styron, a Life . Random House, New York 1998, pp. 451-453.

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens: The Hitch: Confessions of an Indomitable . Blessing, Munich 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Lee Zimmerman: Against Depression , p. 465.

- ↑ For example Laurie Wiener: Choosing Not to Be: On David Foster Wallace . In: Los Angeles Review of Books (Online), November 25, 2012.

- ^ Peter D. Kramer: The Anatomy of Grief: Does Didion's Memoir Do for Grief What Styron's Did for Depression? In: slate , October 17, 2005.

- ↑ Rose Styron: Strands . In: Nell Casey (Ed.): Unholy Ghost . HarperCollins, New York 2001, pp. 126-137; Alexandra Styron: Reading My Father: A Memoir . Scribner, New York 2011.

- ↑ Alexandra Styron: Reading My Father: A Memoir . Scribner, New York 2011. pp. 222-224.

- ↑ Lee Zimmermann: Against Depression , pp. 465-467.

- ↑ Lee Zimmermann: Against Depression , p. 473.