The history of magic in North America

The History of Magic in North America (Original title: The History of Magic in North America ) is a collection of four stories published by the author Joanne K. Rowling in March 2016. The later stories Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (original title Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry ) and Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) (original title The Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) ) become this Collection counted. The stories serve as preparation for the film series Fantastic Beasts and are considered to be forerunners of this.

History of origin

During the development of the script and the shooting of the film Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them , Rowling had gradually announced some rather incoherent details about the American magical world: There is no Ministry of Magic there , but the Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA), which is housed in New York's Woolworth Building and is headed by a President, non-wizards are not called Muggles , but No-Maj (short for No-Magic ), and the name of the American School of Witchcraft and Sorcery is Ilvermorny . In March 2016, Entertainment Weekly announced that Rowling intends to introduce the American magical society and its history and institutions in four texts, entitled The History of Magic in North America , in more detail before it hits theaters . These narratives are based on the details previously disclosed and were published in multiple languages via the official Pottermore site from March 8th to March 11th, 2016 . The stories are about the Magical Congress of the USA , Ilvermorny , the American equivalent of Hogwarts , the Salem witch trials , and the legend of the Native Americans is told, in particular that of the so-called shapeshifters . The stories also show the differences between American and English magic.

End of June 2016 was a continuation of the first four stories the narrative Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (AKA Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry ) published on Pottermore. This reports that the American magic school Ilvermorny was founded by Isolt Sayre and can be found on Mount Greylock . Beginning in October 2016 was followed by the fifth story Magical Congress of the United States of America (Macusa) (original title The Magical Congress of the United States of America (Macusa) ), which, from its beginnings and further developments of the Magic Congress of the United States of America short MACUSA, tells.

The stories serve to prepare for the planned film trilogy Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and are considered to be the forerunners of the series.

content

The texts contained in the collection have the following titles:

- Fourteenth Century - Seventeenth Century (Original title: Fourteenth Century - Seventeenth Century )

- Seventeenth century and later (Original title: Seventeenth Century and Beyond )

- Rappaport's Law (Original title: Rappaport's Law )

- The Magical America of the 1920s (Original title: 1920s Wizarding America )

- Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (Original title: Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry )

- Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) (Original title The Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) )

Contents of Part I: Fourteenth Century - Seventeenth Century

The first part of the series gives a brief overview of the life of witches and wizards between the 14th and 17th centuries . The first magicians living in America were stigmatized for their beliefs. Some descendants of the Native Americans were as Shapeshifter (Engl. Skin Walkers ) are known and the non-wizard (where no-Maj called) assumed them to practice very nasty things. There were also rumors that the shapeshifters sometimes sacrificed their own family members, committed incest with them, or even practiced necrophilia ; the non-wizards liked any insinuation, no matter how evil. As the story progresses, some differences between the Native American people who practiced magic and the European wizards are pointed out. Unlike the Europeans, the Native Americans performed magic without a wand. In addition, the individual European magic communities were better connected to one another.

Contents of Part II: Seventeenth Century and Later

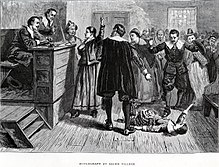

The wizards who came from Europe and immigrated to America lived far across the continent. In America, had immigrated wizard initially without wandmaker get along, and Ilvermorny should only much later develop into a prestigious school of magic. Overall, there were fewer and significantly more Muggle-born witches and wizards than elsewhere. This little magical community of America was poorly organized, lived in secret and in great fear. Persecution by the No-Majs was the order of the day and many magical families went into hiding with their benevolent non-wizards or hiding with Native Americans who welcomed their European brethren. Their greatest fear was the so-called cleaners , a band of wizards who hunted down no-majs and other wizards and got paid for them. The persecution culminated in the Salem witch trials from 1692, in which many wizards, but also non-wizards who had been accused for no reason, had to lose their lives. Magic historians believe that there were also cleaners among the judges.

Contents of Part III: Rappaport's Law

You learn how the no-maj named Bartholomew Barebone , a descendant of a cleaner, found out the secret addresses of MACUSA and the Ilvermorny school and then set out with his friends to track down all the witches and wizards in the vicinity and kill if possible. However, Bartholomew was arrested shortly afterwards and imprisoned for his crime. Nevertheless, Emily Rappaport , the fifteenth president of MACUSA, passed a law in 1790 that aimed at the strict separation between the magical community and the no-maj society. From then on, wizards were no longer allowed to maintain friendships with no-majs. The law drove the American magical community deeper underground.

Contents of Part IV: Magical America of the 1920s

The last story tells of the fact that after the Great Sasquatch Rebellion of 1892 , the MACUSA headquarters had to be relocated for the fifth time in its history, from Washington to New York , and from Madam Seraphina Picquery as its president. In the 1920s , the magical community of North America had got used to having to live under stricter safety regulations than wizards and witches in Europe and exclusively with their own kind. The strict rules that had applied to the use of magic wands for many years were also observed. It is said that Shikoba Wolfe, Johannes Jonker, Thiago Quintana and Violetta Beauvais were the most famous wand makers at the time and caused a sensation in the magical world with their wands. At the end of the story, you learn that unlike the no-majs, American witches and wizards were allowed to drink alcohol in the 1920s .

Contents from Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

The story tells that the witch Isolt Sayre, born in Ireland at the beginning of the 17th century, set out for the New World as a young woman and later became the first in a stone house where she lived with her new family North America Magic School founded. Here she taught not only a number of magically gifted children of the indigenous people, but also many children of the settlers who immigrated from Europe . The children were able to exchange ideas in class. The children of the indigenous people learned how to use magic wands and in turn showed the other students how to do magic the Indian way.

The house, initially made of granite, was later converted into a castle and is located on the highest peak of Mount Greylock . Ilvermorny has a reputation for being one of the most democratic of all the great wizarding schools and has been one of the most renowned magical educational institutions in the world since the 1920s. Unlike at Hogwarts, where the sorting hat determines the distribution among the houses, Ilvermorny's new students are assigned to the individual houses during the assignment ceremony of four magical sculptures.

Contents of the Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA)

The story tells of the beginnings and further developments of the Magical Congress of the United States of America, or MACUSA for short. This was founded after the international confidentiality agreement came into force in 1693. Many witches and wizards were convinced after the Salem witch trials that one could live more freely and happily if an autonomous administration with its own structures was created.

The initial goal of MACUSA was to bring the cleaners to justice who had betrayed their own people. In addition, it was planned to jointly pass laws that should regulate the coexistence of the American magical community and at the same time serve their protection. For this purpose, representatives were elected to MACUSA from all magical communities in North America. The first president of MACUSA was Josiah Jackson . From 1760, the MACUSA was located in Williamsburg , Virginia , home of the eccentric President Thornton Harkawa . He later moved to Baltimore and then to what is now Washington . After the Great Sasquatch Rebellion of 1892, the MACUSA headquarters had to be relocated for the fifth time in its history, from Washington to New York , where it is housed in the Woolworth Building . In advance, the magicians had infiltrated the construction team of the building under construction and, through magic, created a lot of space for the MACUSA, which was hidden from the eyes of No-Majs and only accessible if the correct magic was used.

reception

Chris Lough criticizes that Rowling starts her story well and also captivating, but in the further course she has to turn some true historical events upside down and combine them with fiction, which she manages well in some places. It convincingly interweaves the Native Americans of the 14th century and shows easily understandable similarities and differences with the European population of the time without adding unnecessary complexity, says Lough. It is easy for the reader to understand that, because of their well-known history, the Native Americans were more willing to incorporate wizards into their community. Nonetheless, Lough also suggests that Native American reactions can be expected when a writer tries to fit human historical heritage into his own fictional world.

Dave Thier of Forbes also generally thinks it's not a bad idea to expand the world of Harry Potter, adapting it to an American context and speaks of an interesting idea to see what happens when you mix British and American cultures. However, after the publication of the texts in March 2016, Thier criticized that, as a native of England, Rowling did not know the history and culture of the nation she was writing about well enough and was also familiar with the treatment of Indians in America, with the events there during the colonial era and little familiar with the consequences of segregation . Adrienne Keene expresses her criticism, especially of the first story by referring to the use of established clichés and the cultural appropriation of the indigenous peoples by Rowling: “It is not 'your' world. It is our (real) world of the indigenous people, in which shapeshifter stories have a context, their roots and a reference to reality. "

Individual evidence

- ↑ JK Rowling: The History of Magic in North America In: pottermore.com. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ Big surprise! Harry Potter Author JK Rowling Releases Four New Magic Stories In: Focus Online March 8, 2016.

- ↑ a b c J. K. Rowling: Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) In: pottermore.com. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ James Hibberd: Fantastic Beasts: 5 secrets in our photo you might have missed In: Entertainment Weekly, November 6, 2015.

- ↑ James Hibberd: Fantastic Beasts: JK Rowling reveals the American word for 'Muggle' In: Entertainment Weekly, Nov. 4, 2015.

- ↑ Ilvermorny - The American Wizarding School In: fantasticbeastsmovies.com, January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Lily Karlin: Finally, The Name And Location Of JK Rowling's American Wizarding School In: The Huffington Post, January 30, 2016.

- ^ JK Rowling: Fourteenth Century - Seventeenth Century In: pottermore.com, March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Kevin P. Sullivan: New JK Rowling stories will explore American wizarding history In: Entertainment Weekly, March 7, 2016.

- ↑ 'History of Magic in North America' starts today on Pottermore In: pottermore.com, March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Kevin P. Sullivan: JK Rowling's first Magic in North America story explores Native American wizards In: Entertainment Weekly, March 8, 2016.

- ^ Christian Holub: The week in JK Rowling: Annotating magical history and celebrating women In: Entertainment Weekly, March 11, 2016.

- ↑ New Ilvermorny writing and Sorting Ceremony by JK Rowling now on Pottermore In: pottermore.com, June 28, 2016.

- ↑ a b J.K. Rowling: Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry In: pottermore.com. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ↑ 'Harry Potter' author JK Rowling publishes four new magic stories In: Focus Online, March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Chris Lough: JK Rowling No: The Opportunism of 'History of Magic in North America' In: tor.com, March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Dave Thier: 'Magic In North America:' JK Rowling Is Channeling George Lucas, And Not In a Good Way In: Forbes Online, March 12, 2016.

- ↑ Adrienne Keene quoted in: JK Rowling's History of Magic in North America draws criticism for cultural appropriation In: CBC Radio Online , March 13, 2016.