Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (film)

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone |

| Original title | Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone |

| Country of production | United Kingdom , United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 2001 |

| length |

Theatrical Version: 152 minutes Extended Cut: 159 minutes |

| Age rating |

FSK 6 (Theatrical Version) FSK 12 (Extended Cut) JMK 6 |

| Rod | |

| Director | Chris Columbus |

| script |

Steven Kloves , Joanne K. Rowling (Consultant) |

| production | David Heyman |

| music | John Williams |

| camera | John Seale |

| cut | Richard Francis-Bruce |

| occupation | |

| |

| chronology | |

|

Successor → |

|

The British - American fantasy film Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (original title Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone , published in the USA as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone ) from 2001 is the film adaptation of the first Harry Potter novel of the same name - Children's book series. It was directed by Chris Columbus from a screenplay by Steven Kloves and was produced by David Heyman . Joanne K. Rowling , the author of the book, exerted a strong influence on the faithful film adaptation of her successful debut novel.

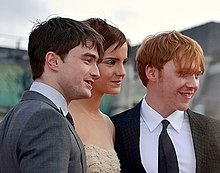

The focus of the story is Harry Potter , who learns on his eleventh birthday that he is a wizard and is called to the Hogwarts School of Magic . During his first year of school, the orphan boy gets to know the wondrous world of magic, goes through various adventures and is finally confronted with the dark magician Lord Voldemort . The film was almost exclusively cast with British actors, the many children's roles with young actors who were largely unknown until then. The title character is played by Daniel Radcliffe , with Rupert Grint and Emma Watson as Harry's best friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger in other leading roles .

After a preview on November 4, 2001 in London, the film was released on November 16 in Great Britain and the USA and on November 22, 2001 in Germany. The press rated the film differently. Above all, she criticized the fact that he reproduced too many content-related details of the novel in quick succession without taking time to develop an atmosphere. With the exception of the main actor, the cast was judged mostly benevolently. The production design and effects were also mostly praised, in contrast to the music. Despite mixed reviews, the film achieved gross revenues of around 975 million US dollars worldwide, making it one of the most commercially successful films at the time. He received three Oscar nominations for production design, costume design and film music , and was nominated for a BAFTA Award in seven categories .

action

The orphan boy Harry Potter grows up in Surrey with his aunt's bourgeois family, the Dursleys , who treat him very badly. So Harry has to sleep in a closet under the stairs and has to suffer from the harassment of his spoiled cousin Dudley . Shortly before his eleventh birthday, Harry receives a letter which - still unopened - is taken away from him by the Dursleys. More and more letters are being delivered to him by owls, which his uncle withholds from him. It wasn't until the gigantic Rubeus Hagrid shows up on his birthday that Harry learns to his surprise that his parents were wizards. They were killed by the dark magician Lord Voldemort . Harry survived the attack unscathed except for a lightning bolt scar on his forehead, and Voldemort lost his strength trying to kill the one-year-old child. That's why Harry is a legend in the wizarding world. The Dursleys withheld this from Harry because as non-wizards - so-called " Muggles " - they abhor everything magical and are afraid of it. Hagrid hands Harry one of the letters; it's an invitation to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

Hagrid, the school ranger, leads Harry to hidden Diagon Alley in London, where he can buy teaching materials such as books and a wand . For his birthday Harry gets the owl Hedwig from Hagrid . He also gives him a ticket for the Hogwarts Express , which takes the Hogwarts students from platform 9 ¾ of London's King's Cross Station to the remote magic school. On the drive, Harry meets two of his future classmates: the redhead Ron Weasley , with whom he gets along straight away, and the cleverly wise Hermione Granger .

Once at Hogwarts Castle Boarding School, the Sorting Hat assigns the students to the four school buildings : Gryffindor , Hufflepuff , Ravenclaw and Slytherin . Harry, Ron and Hermione come to the Gryffindor house. Starting the following day, students are trained in various disciplines of wizardry, including transmutation, potions, Defense Against the Dark Arts, and broom flying . For the latter, Harry shows an extraordinary talent, which is why he is accepted into the Quidditch team of Gryffindor. This team sport is played on flying brooms, and Harry can win the first game against Slytherin for his house. A close friendship develops between Harry, Ron and Hermione. Harry finds a rival and archenemy in a Slytherin classmate of the same age, Draco Malfoy .

Meanwhile, Harry, Ron and Hermione have found out that something valuable at school is guarded by a three-headed dog. Your research reveals that it is the philosopher's stone , which gives immortality to its owner. On special instructions from Headmaster Albus Dumbledore , the stone is kept and guarded in the school after an attempt to steal it from Gringott's wizarding bench has been foiled . Harry suspects the potions teacher, Professor Snape , who he suspects of being in the service of Lord Voldemort , is behind it . Harry also believes that Snape was using the stone to restore Voldemort to human form and to new power and greatness.

Harry, Ron and Hermione decide to look for the stone themselves in order to find it before Snape. You will conquer a series of obstacles designed to protect the stone: a deadly plant, the hunt for a flying key, and a violent, larger-than-life game of chess. Harry penetrates into the hiding place of the stone and finds Professor Quirrell , the inconspicuous teacher for Defense Against the Dark Arts. When Quirrell removes his turban, it is revealed that Voldemort has taken possession of his body. The stone is protected by a spell: only those who want to find it without using it can obtain it. So Voldemort gets Harry to take the stone and tries to trick the boy into giving him the stone. When Harry stands firm, Quirrell tries to kill Harry, but Harry's touch turns him to dust. Voldemort leaves Quirrell's body and flees, Harry faints. After recovering in the hospital wing, Dumbledore explains that Harry was inviolable to Voldemort because his mother sacrificed herself for him. He also reports that the Philosopher's Stone has since been destroyed to avoid falling into Voldemort's hands.

The school year traditionally ends with a big party in the Great Hall . The house cup is awarded to one of the four houses, and Gryffindor was actually in last place with his score. In the light of the previous events, Hermione, Ron, Harry and also Neville were awarded extra points, and so Gryffindor was the winner in the last few meters.

At the end of the film, Hagrid gives Harry a photo album with pictures of his parents just before the Hogwarts students return to the world of "Muggles".

Production history

Pre-production

Idea and purchase of rights

British producer David Heyman was looking for a 1997 children's book to it for a family-friendly movie adapt . An employee of his production company Heyday Films suggested the recently published debut novel by Joanne K. Rowling - a fantasy book called Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone , which critics praised and which was about to become a bestseller . Heyman took a liking to the book and was in regular contact with the author. It was only after the publication of the second Harry Potter novel in July 1998 that Heyman proposed to the American film company Warner Bros. the adaptation of the first book.

Because Rowling did not want to give control of her work to someone else's hands, she initially rejected an offer from Warner as well as offers from some other companies. Only when the studio guaranteed her considerable say in the implementation of the film, possible successors and the merchandising products, did she agree to the filming. By this time a cult around Harry Potter had already developed in Great Britain ; in the USA, where the first book had just appeared, the wizarding student was still largely unknown, so Warner was cautious about the market potential outside the UK. What the group paid for the film rights in addition to a profit-sharing scheme is quantified differently in various sources: it should have been $ 500,000, $ 700,000 or $ 1 million; others cite £ 1 million (then just under $ 1.7 million) for filming the first four volumes.

Heyman described the influence that Rowling ultimately exerted on the entire production as “ tremendous ” (German: “enormous”). She was involved in all major pre-production decisions. This includes the personal details of the director, the screenwriter and the most important actors. She was also a consultant for the development of the script . She insisted that all actors should be British and that British English be spoken in the film . She also played a key role in determining the visual style of the film - for example the appearance of the set design, costumes, mask and props.

Selection of the director

Hollywood great Steven Spielberg was initially discussed as a director . In February 2000, however, he canceled because, as he later said, the project was not a challenge for him. Talks then began with a host of other directors, including Tim Burton , Chris Columbus , Jonathan Demme , Terry Gilliam - a Rowling favorite - Mike Newell , Alan Parker , Wolfgang Petersen , Tim Robbins , Rob Reiner , Ivan Reitman , Brad Silberling , Guillermo del Toro , M. Night Shyamalan , and Peter Weir . At the end of March 2000, the choice fell on Chris Columbus, who had already directed successful family films such as Kevin - Alone at Home and Mrs. Doubtfire . According to Heyman, it was above all Columbus' desire to remain as faithful to the novel as possible that ultimately tipped the balance in his favor.

Script development

In early 1999, Warner Bros. had proposed a number of novels to American screenwriter Steven Kloves for reworking into a script, including Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . Kloves was convinced of the template and accepted the task. Kloves kept in close contact with Rowling to ensure that small details remained consistent when translating text into film. At the same time, this prevented the film from contradicting later, as yet unreleased parts of the series. As far as Kloves added his own dialogues, he tried to interpolate the novel , and Rowling approved the parts she thought fit. In retrospect, Kloves described the work on the script as difficult because the novel was the least story-heavy of the Harry Potter books. He creates the basis for later developments and thus contains fewer narrative parts than his successors.

Cast

The casting director named Susie Figgis , who had earned a reputation for selecting actors for productions such as Gandhi , Interview with a Vampire or The Full Monty . Together with Rowling and Columbus, she set in motion a multi-stage process to cast the leading roles of Harry Potter, Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger. Only British children between the ages of nine and eleven were considered. You first had to read a page from the novel; Those who were convincing were invited to improvise a scene from the students arriving at Hogwarts and, in a third step, read a few pages from the script. The casting was finally advertised publicly. At the beginning of the summer of 2000, Figgis left the project early after several thousand young British actors had been sighted without any of Chris Columbus or the producers being classified as "worthy of the role". The other casting was done by Janet Hirshenson and Jane Jenkins .

There had been around 40,000 applications for the main role alone. Various well-known young American actors had expressed their interest in the role, including Haley Joel Osment (then twelve years old, Oscar- nominated for The Sixth Sense ), Eric Sullivan (nine years, Jerry Maguire ) and Liam Aiken (ten years, page at side ), but failed because of Rowling's request to fill the title role with a British man. William Moseley , who later starred in the feature film series The Chronicles of Narnia , was also turned down.

On August 21, 2000, Warner Bros. finally announced that the choice for the lead role had fallen on Daniel Radcliffe, who had previously been largely unknown in the film business ; film newbies Emma Watson and Rupert Grint had been selected for the roles of Hermione and Ron, respectively. With the exception of Radcliffe and Tom Felton , who played Draco Malfoy, most of the children's roles were cast by inexperienced actors who had previously only appeared in school theater productions.

Columbus had wanted Radcliffe in the role of Harry Potter since seeing him on a BBC television movie. However, this initially prevented Radcliffe's parents, who both worked in the casting industry to protect their son from public pressure. Only after Heyman, a friend of Radcliffe's father, convinced the parents that they could protect their son from the expected media hype , did they give their consent. Rowling also said that you couldn't have found a better Harry. Radcliffe's earnings from the film are estimated at a million pounds.

Rupert Grint had applied for the role of Ron Weasley with a self-made video after learning about the auditions on television. In contrast, Emma Watson was considered a long-time member of her school theater group after a suggestion from her theater teacher and an audition at her school in front of casting agents.

Rowling influenced the selection of most adult performers. She specifically challenged Robbie Coltrane for the role of Rubeus Hagrid. Others like Richard Harris as Professor Dumbledore, Maggie Smith as Professor McGonagall and Alan Rickman as Professor Snape came from a cast wish list that Rowling presented to the producers. Many of the adult actors are members of the Royal Shakespeare Company . Rowling's requirement to occupy only British was largely complied with; the few exceptions in more important roles are the Irishman Harris, his compatriots Fiona Shaw as Petunia Dursley and Devon Murray as Seamus Finnegan and the New Zealander Chris Rankin as Percy Weasley . For a detailed list of the most important roles and their occupation see section German dubbed version .

Choice of locations

In 1999 representatives of the British film industry negotiated with American donors that the film would be shot in Great Britain. In return for the fact that most of the money was spent on the production in Great Britain, the British film industry provided support in the selection of locations and provided Leavesden Film Studios near the town of Watford . According to a report by the US magazine Entertainment Weekly , promises have even been made to try to change the British labor regulations for children, which should allow more flexible and longer filming times. Steve Norris , who as head of the British Film Commission was responsible for making the film in Great Britain, summed up Harry Potter's relation to his homeland as follows:

Harry Potter is something that is weirdly about us. It's culturally British and the thought of it being made anywhere but here sent shudders down everyone's spines. It's like taking Catcher in the Rye and setting it in Liverpool.

“ Harry Potter is something that has we [British] about us in weird ways. It's British culture, and the thought of it being done anywhere else than here makes everyone shudder. It's like taking the catcher in the rye and moving it to Liverpool . "

The scenes that take place in actual locations in the book - such as the reptile house at London Zoo and King's Cross train station - were also filmed there. The filming location for the fictional platform 9 ¾ was platforms 4 and 5 at King's Cross.

A real counterpart has been found in more or less prominent places in Great Britain for a number of fictional locations: Picket Post Close in Martins Heron , a suburb of Bracknell , served as Privet Drive ; house number 12 corresponds to the Dursley's house. Scenes in Diagon Alley were filmed in Leadenhall Market , London ; a then vacant shop in Bull's Head Passage number 42 was used as an entrance to the pub Zum Tropfenden Kessel . The interior shots of the magic bench Gringotts come from Australia House, the seat of the Australian High Commissioner on London Street Strand . The Hogwarts Express actually ran on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway , whose Goathland station became Hogsmeade station .

Several locations were chosen for the Hogwarts Magic School to maintain the impression that the magic boarding school is not in a real location. The walls of Alnwick Castle provided the outside view, its long, flat green spaces the Quidditch field. Recordings for the hallways and corridors are from the cloisters of Lacock Abbey , Gloucester Cathedral and Durham Cathedral . The warming room of the former also provided the backdrop for Professor Quirrel's classroom, and the latter's chapter house that of Professor McGonagall. Professor Flitwick's room, on the other hand, is in the Harrow English School . Various Oxford University buildings also contributed to the film architecture of Hogwarts: The Duke Humfrey's Library, part of the Bodleian Library , represents the library of the School of Magic , the Divinity School its hospital, and the College Christ Church the trophy room.

- Different locations

Filming

The shooting began in October 2000 at the station Goathland. Despite various countermeasures, details of the shooting were made public, such as photos of the scenery or of the shooting itself.

A school was set up in the studio for the 450 or so children who participated in the production. The main characters Radcliffe, Grint and Watson were filming for four hours a day; they had three hours of instruction; the rest of the time was available to them as free time.

Since the film was to be published in the USA under the different title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone , according to the book , all scenes in which the words “ Philosopher's Stone ” occurred were rotated twice to to replace the word “ Philosopher’s ” with “ Sorcerer’s ”. Other formulations that had been translated from British to American English for the US edition of the book were retained in the film. Today, such changes are usually made through subsequent synchronization.

Due to various delays, the shooting period had to be extended several times and finally ended in April 2001, with some reworking done in July.

Costumes and mask

For costume designer was Judianna Makovsky determined that recently for their work on the film Pleasantville - Too good to be true for an Oscar had been nominated. She initially designed the jerseys for the Quidditch players based on the template of the cover of the American edition of the novel by Scholastic , which shows Harry in a modern rugby jersey, jeans and a red cape. The copy was too messy and too little elegant, so they missed the players to the capes preppy sweaters and ties, sport riding pants and arm.

Responsible for the mask was Clare Le Vesconte . It had to be clarified early on where exactly on Daniel Radcliffe's forehead Harry Potter's external trademark, the lightning-shaped scar, should be placed. Book covers were not very helpful as a template for this question because the various international editions showed the scar in different places. Therefore, director Columbus sought advice directly from Rowling: he painted a face with a magic hat and asked her to draw the scar. She referred to the scar as “ razor sharp ” (German: “razor sharp”) and drew it pointing downwards on the right side of the forehead.

Production design

The production design was designed by British Oscar winner Stuart Craig . He made several film sets at Leavesden Film Studios, including the great hall at Hogwarts. Since the history of Hogwarts goes back to the Middle Ages, he was inspired by the largest English cathedrals of the time, but also by the College Christ Church. The architecture should be realistic, but “ pushed as much as we can, expanded as illogically huge as we can possibly make it ” (German: “exaggerated, as well as we could, oversized into the illogical, as far as we were somehow feasible "), Says Craig. For reasons of cost, a real filming location was originally intended to be found for Diagon Alley, but none of them met the high requirements: The first glimpse into the world of wizards should visually overwhelm Harry and the audience. Ultimately, Craig built a cobblestone street at Leavesden Film Studios, which he lined with buildings in Tudor style , Georgian architecture and Queen Anne style - a mix of styles that was nowhere to be found in a real street.

Special effects

To bring magic, fantasy creatures, flight scenes and the like onto the screen, Chris Columbus planned a combination of special effects and computer-generated images . The animatronic process should be used for various of the fantastic figures and creatures, such as the three-headed dog . British effect artists Nick Dudman and John Coppinger contributed dolls, film prostheses and make-up effects for unreal living beings , supported by the Creature Shop run by US doll maker Jim Henson . Because the director and the producers attached great importance to optically coming as close as possible to the specifications of the book, characters often had to be designed in more than one version or changed afterwards. According to Coppinger, a particular challenge was to design mythical creatures that not only appear in the Harry Potter novels - for example unicorns - in such a way that they did not convince with a “new” or “exotic” appearance, but with the greatest possible realism . Some scenes were realized with the help of model buildings, for example when owls fly over the roofs of houses or some of the exterior views of Hogwarts.

post processing

Visual effects

The special effects were rounded off by a variety of computer-generated visual effects during post-production . For example, a four meter tall troll and a baby dragon were created as computer animations . The moving stairs at Hogwarts were partly built in the studio and later digitally post-processed. Radcliffe, whose eyes are blue and not green like Harry Potter's, had to wear colored contact lenses when shooting. Since these turned out to be very annoying, his eye color was subsequently standardized on the computer. In the film, Harry can ultimately be seen with blue eyes. The blue screen technique plays a significant role in the Philosopher's Stone . In total, the film has around 500 to 600 such effects, which were contributed by various specialist companies: Industrial Light & Magic modeled the face of Lord Voldemort, for which no separate actor was hired; Instead, Quirrell actor Ian Hart was the godfather for the CGI model of the face. Rhythm & Hues animated the baby dragon, Sony Pictures Imageworks produced the effects-heavy Quidditch scenes, which are considered to be the most complex animation work in the film. In total, the film's end credits list nine film trick companies, coordinated by Robert Legato . Half of the budget is said to have been spent on the tricks .

Final cut

The Australian film editor Richard Francis-Bruce was responsible for the editing . Director Columbus knew that the film would be very long without major omissions. Nevertheless, he wanted to avoid them if possible so as not to disappoint the fans. His argument was a comparison with the fourth book in the series, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire , published in July 2000 : “ Kids are reading a 700-page book. They can sit through a 2½ hour movie. ”(German:“ Children read a 700 page book. Then they can sit still during a two and a half hour film. ”) Nevertheless, some scenes were removed in the final cut, including the appearances of Poltergeist Peeves and the last hurdle on the way to the stone Wise, a Potions teacher Snape's poison puzzle that Hermione solves. The theatrical version lasts 152 minutes, the long version 159 minutes.

Film music

One of Hollywood's most famous film composers, John Williams , with whom Columbus had already worked on the films Kevin - Alone at Home and Side by Side , was hired for the music . In preparation, Williams read the novel. He had not done so in other cases before, in order to be impartial like the majority of the cinema audience. He composed the individual pieces of music in Tanglewood and in his apartment in Los Angeles. He was inspired by classical composers. The references to Tchaikovsky , for example from the ballets The Nutcracker or Swan Lake, are clear . At the same time, Williams' first priority was to compose music for children, that is, for an audience with less developed listening habits.

A theme that he had designed for the owl Hedwig, he developed into a musical leitmotif for the film, because “ everyone seemed to like it ” (German: “ everyone seemed to like it ”). It was used in the first trailer for the film and was shown on July 31, 2001 at a concert during the Tanglewood Summer Festival. In both cases the reactions were exceptionally positive.

The recordings for the film were made in the London studios Air Lyndhurst and Abbey Road . Williams could not use the London Symphony Orchestra as planned and resorted to other London musicians, including the choir of London Voices .

German dubbed version

The German dubbing was done by FFS Film- & Fernseh-Synchron München and Berlin . The dialogue book was written by Frank Schaff , who also directed the dubbing and also spoke two roles.

Film analysis

Comparison with the novel

Differences in plot

The film adaptation stays very close to JK Rowling's book. A comparison of the individual film scenes with the corresponding passages of the novel shows that the plot of the novel was transferred almost one-to-one into the film; significant changes, omissions or additions are rare.

Various supporting characters do not appear in the film, including the teacher of the history of magic Professor Binns, the poltergeist Peeves , a friend of Dudley Dursley named Piers Polkiss and Mrs. Figg , a neighbor of the Dursleys (Mrs. Figg did, however, in the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix made their first appearance in the film series, as their literary significance could not be foreseen at the beginning of the shooting of the first film. Their backstory from the books is therefore not taken into account.) It begins with the scene in which Harry is with his foster parents is given, thus skipping almost the entire first chapter of the novel. The attempts of the Dursleys to flee from the masses of incoming letters were cut. Other scenes have been left out entirely, including Harry's first encounter with Draco Malfoy in Diagon Alley - in the film they meet for the first time at Hogwarts - and the first duel between the two adversaries, the Song of the Talking Hat, the Quidditch game against Hufflepuff, and Snape's riddle and Quirrel's now incapacitated troll on the way to the Philosopher's Stone. Also, Harry does not find out in the end why Professor Snape hates him and that Dumbledore gave him the Invisibility Cloak.

Other scenes have been fundamentally changed. For example, Harry, Hermione and Neville and Malfoy have to do criminal duty in the accounts because they are caught by caretaker Filch and Professor McGonagall sneaking through Hogwarts at night. In the film version, it is Harry, Hermione and Ron who have to serve the sentence with Malfoy because Malfoy reveals that they snuck up to Hagrid's hut that night. In addition, the friends in the book help Hagrid to get the dragon Norbert to Ron's brother by taking him to the astronomy tower at night where he is picked up (they are caught by Filch). Instead, Hagrid mentions in the film that the dragon was sent to Romania by Dumbledore. In the book, Harry is given an album of photos of his parents by Hagrid in his hospital bed after his confrontation with Voldemort. The film moves this scene to the end of the story, to say goodbye to the train station. The photo album can also form the bridge to the second film , where Harry takes a close look at it in his room.

Finally, a number of smaller details were modified: the snake in the zoo is a boa constrictor from Brazil in the book , a python from Myanmar in the film . While Dudley and Petunia Dursley are described as blonde in the book, they are brunette in the movie. The hair color of the centaur Firenze has also been changed from light blonde to dark. The film moves the Quidditch pitch from a classic stadium to an open space surrounded by towers.

Effects of differences

On the content level, the individual deviations from the template trigger different reinterpretations. Two essential points can be identified as the shortening and simplification of the story on the one hand, and on the other hand the weaker weighting of the dark parts of the plot and thus a shift in the overall impression towards the friendly and harmless.

The first point primarily takes account of the need to change media by ensuring that it is gathered together and saves time. Cutbacks were made when the script was being written. For example, Kloves suggested Rowling to change how the dragon disappears. The author said she had difficulty writing the book version of this scene herself, so this change was the easiest for her to accept. On the other hand, the appearances of Peeves and Snape's Riddle were only removed in the cut , because otherwise the film would have been too long. The concise presentation of the film leaves little room to prepare developments for the later parts of the Harry Potter series. For example, due to the postponement of the first meeting of Harry and Malfoy, little is learned about Ron's house rat, which becomes more important as it progresses.

The second point, the more carefree mood, is achieved partly through further omissions, partly by giving the negative action phases a smaller share of the overall work. The film does not show various scenes in which Harry and his friends behave aggressively and break rules: In the book, Harry is determined to fight a magical duel with Draco Malfoy, which reveals the hostility he feels for his opponent; To get to the duel, the friends sneak through Hogwarts at night, disregarding express prohibitions and warnings. During the second Quidditch game, which does not appear in the film, there is a fight between Ron and Malfoy, which is also joined by Neville, Crabbe and Goyle. The rescue operation for the dragon Norbert, which takes up an entire chapter in the book, shows that the friends are ready to accept rule breaking and dangers out of solidarity with Hagrid. With the omission of these plot elements, the combative and idiosyncratic sides of the character are suppressed, and the film Harry seems more well-behaved and less emotional than his comparatively cheeky and daring novel counterpart. In addition, for example, the action phase, in which Harry's increasing threat from Voldemort is conveyed, takes up proportionately less space in the overall work, namely around 9 percent of the film minutes compared to around 15 percent of the book pages. In return, the action-packed and positive parts of the plot are quantitatively upgraded.

Film-specific design tools

music

For the background music for the film, composer John Williams created various catchy themes , which he mainly uses as leitmotifs . Your late-romantic embossed and her großorchestraler structure in line with earlier works of the musician and in particular his work on the films Hook and Star Wars: Episode I comparable.

The main theme of the film is dedicated to the world of wizards, symbolized by the owl Hedwig. However, it is not to be equated with the Hedwig’s Theme suite , at the beginning of which it can be heard and with which it is occasionally confused. The waltz- based theme is introduced right at the beginning of the prologue and appears again and again in the course of the plot as a hallmark of the magical, often played by a celesta , whenever the magical and the strange have to be emphasized. In this function it dominates the scenes up to the arrival at Hogwarts, but is also used in later scenes, for example when looking at the moving stairs or during the Quidditch game. A second theme, a march , stands for Hogwarts Castle. It is similar to the world of magic theme heavily in the progression and can be seen as its continued development. Both end in a minor third that conveys a mysterious mood. It makes its most prominent appearance when you first see the castle. The action element flying is highlighted with its own theme: After a driving first part with brass , bass and carillon , the strings play a calm, rising note run. This topic is primarily associated with Quidditch, but it can also be heard quite prominently during the introduction of the students to the flying broom.

Williams wrote two character themes for the main character Harry Potter and for his nemesis Lord Voldemort. The powerful theme for Harry unfolds optimistically and culminates in heroic fanfares . It illustrates Harry himself, his growing friendship with Ron and Hermione, and the connection he feels with his late parents. The theme for Voldemort is a somber variation on the Wizarding World theme. With the help of a tritone it gives the black magician a particularly threatening effect. In addition, it is divided into two parts - the first from three, the second from four notes - which are used individually as counterpoint when something mysterious happens.

The leitmotifs, which initially underline elements of the plot or indicate people, acquire additional meaning by subtly commenting on the event. This becomes clear in the use of the Voldemort motif, which sounds, for example, while Harry's other enemy, Draco Malfoy, is judged by the Sorting Hat. It also appears in the zoo scene, in which Harry discovers that he can communicate with snakes, and musically indicates Harry's connection to Voldemort. When the film's decisive moment in the struggle between good and evil comes, the argument between Harry and Voldemort, the two leitmotifs are combined and juxtaposed in such a way that the musical level reflects the drama of the struggle.

There are also passages in the film music that do not serve as a leitmotif. This includes sound carpets that reproduce the mood of the respective scene on the sound level and thus reinforce it, such as cheerful flute playing in Diagon Alley or oppressive tension music in the Forbidden Forest. Elsewhere, the background music helps to emphasize content, for example by adding accents to important points or suddenly breaking off background music before decisive words are said.

Camera and editing

Camera work and editing are only used cautiously as design elements. The film is characterized by wide camera angles and top views, which allow a view of many details, as well as a few cuts.

Often, high perspective angles are used to convey meaning to a person. In conversations, the more dominant is always shown from below, and the person opposite is shown from above using the shot-reverse shot method. An example of this are Harry's encounters with the strict and terrifying teacher Snape. In the case of Hagrid, the change of perspective also illustrates the enormous size of the giant.

The film gets by with relatively few cuts. Cuts are sometimes bypassed by tracking shots. To control the tension, the cutting speed is hardly increased - as is usual. Even in the most action-packed part of the film, during the Quidditch game, the average length of a shot of around 2.3 seconds is far above what is common in action scenes in feature films. This is compensated for on the sound level: In addition to driving suspense music, the game is accompanied by various sound effects that acoustically reproduce the movements through the air with whistling or hissing sounds. The focus on a young target audience can be assumed as the motive for the low frequency of cuts, because too fast cutting sequences are not suitable for children.

In a few places the use of the camera goes beyond what was already laid out in the book. An example of this can be a scene after Harry received his father's advice from Dumbledore not to indulge too much in the dream of seeing his dead parents again: Harry walks into a snow-covered courtyard of Hogwarts with his owl Hedwig in his arms and looks after her to see how she takes off in a slow flight. The camera follows the bird until it disappears into the white of the clouds. When it reappears, the lush green of the landscape indicates that spring has come. By accompanying the symbolic flight of the owl, the camera can not only convey a time lapse purely visually. Kloves added the scene to the script to move the viewer. At the same time, the images of poetic cinematic strength create a moment of calm in which Dumbledore's words can linger before the action continues.

publication

The first film posters were put up in the run-up to Christmas 2000. The first English language trailer was released on March 1, 2001 via satellite television . The next day it was seen for the first time in cinemas before the film spot . At the same time, an internet-based guerrilla marketing campaign was started with the trailer.

The world premiere of the film took place on November 4, 2001 in a cinema redesigned as Hogwarts in Leicester Square , London, in front of invited guests. The film opened in regular cinemas in Great Britain and the USA on November 16, and six days later - with a midnight premiere - also in Germany.

In the US, the film was published under the different title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone , under which the novel was published there. The publisher Scholastic had changed the title of the book to avoid associations with philosophy through the word " Philosopher " (German: "Philosopher"). Instead, “ Sorcerer ” (German: “Magician”) should clearly refer to the subject of magic . The decision was criticized because the " Philosopher's Stone " (German: " Philosopher's Stone ") the reference to alchemy was lost (see requirements and Editions of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone ).

In total, the film was translated into 43 languages and played on more than 10,000 movie screens.

For the home cinema market, Warner Bros. released the film on May 11, 2002 in DVD region 2 (including Western and Central Europe) and on May 28, 2002 in region 1 (USA and Canada), initially on DVD and VHS . The film was later distributed on HD DVD and Blu-ray Disc . The film was shown for the first time on free TV in the USA on May 9, 2004 on ABC , in Switzerland on September 3, 2005 on SF 1 and in Germany on October 2, 2005 on RTL .

aftermath

Age ratings controversy

In Germany and Austria, the film was released from the age of six . In the UK and the US, it was rated PG , which recommends that children watch the film with their parents. Denmark and Sweden, for example, set higher age limits, where going to the cinema was only permitted from the age of eleven.

In Germany, the release sparked a public controversy in which politicians, church representatives, parents and members of the press spoke up. As the most contentious aspect of the debate, the Voluntary Self-Control of the Film Industry (FSK), which is responsible for the age ratings in Germany, identified the question, "To what extent the content of magic or black magic can frighten and disorient children from the age of 6." Member of the Bundestag Benno Zierer ( CSU ) warned of the effects of the film on small children: “So much occultism is dangerous for six-year-olds . They are not religiously stable and believe everything they see. ”He suggested“ not showing the film in Germany until we know what effects it is having in other countries ”and called on the Minister of State for Culture to intervene. The MP Ingrid Fischbach ( CDU ) tried to get a decision through the Children's Commission of the German Bundestag . However, neither committee saw any need for action. According to representatives of the Protestant and Catholic Churches in Germany, the film was also suitable for children. They ruled out an occult threat. Parents who wrote to the FSK showed mixed reactions. While some reported the greatest concern for children under the age of twelve, others announced that they would also watch the film with their four-year-old child. Because of the high pace and some creepy scenes, various newspaper reviewers recommended that children only be allowed to go to the cinema from the age of eight or nine. The film service considers the film to be suitable for children aged ten and over.

Even after the novels were published, a dispute broke out , especially in the USA, about the danger to children from the Harry Potter stories. Representatives of Christian churches had warned against a “temptation to the occult” and the “glorification of Satanism” and had achieved that the novels were indexed and removed from various libraries. Similar controversies have raged in many places, such as Australia, Great Britain, Italy and Austria.

Financial success

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

* Box office income including Ireland and Malta |

The cost of producing the film is estimated at $ 125 million, other sources put it at $ 130 million or $ 140 million. Another $ 40 to 50 million is said to have been spent promoting the film.

The theatrical release of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone was extremely successful. The film set several box office records worldwide. On the first weekend, box office profits of 90.3 million US dollars in the USA and Canada, and 16.3 million £ in Great Britain were just as unmatched as the number of visitors of over 2,590,000 in Germany, more than 220,000 in Austria and around 136,000 in the German-speaking Switzerland. The start record in Germany has not yet been broken (as of January 2014). For more than 10 million cinema tickets sold in Germany in 100 days, the film was also honored with the Bogey in Titanium , and for over 12 million viewers it was awarded the three-star golden screen .

In total, more than 58.5 million people saw the film in the US, over 17.5 million in Great Britain, over 12.5 million in Germany and around 1 million each in Austria and Switzerland. It grossed over $ 317 million in the US and Canada, over £ 66 million in the UK and over $ 974 million worldwide. The largest market after North America was Japan with the equivalent of around 153 million US dollars.

This made it the world's most successful cinema production of 2001. It was the most watched film of the decade in German cinemas and moved to fourth place among the most watched films of all time , which it has held since then (as of January 2013).

It ranks 47th (as of August 8, 2020) in the list of the most successful films of all time .

The revenues from the DVD distribution and the sale of the television rights are estimated at 600 million US dollars each. The sale of merchandising licenses brought about 150 million US dollars from Coca-Cola , a further 50 million US dollars from the toy manufacturer Mattel . The many other licensees include Lego and Hasbro ; In total, license sales exceed $ 300 million.

Reviews

The film was received differently by international critics. While the British press praised him primarily, the voices in the US and Germany were more subdued. The range of the individual ratings extends from “ a classic ” (German: “a classic”), according to Roger Ebert for the Chicago Sun-Times , who ran the film in a series with The Wizard of Oz , Charlie and the Chocolate Factory , Star Wars and ET - The extraterrestrial saw, right up to the judgment of Elvis Mitchell , who wrote for the New York Times that the film was “ dreary ” (German: “monotonous”) and marked by a “ lack of imagination ” (German: “Lack of Imagination "). The Rotten Tomatoes website , which compiles an index from collected English-language reviews, calculated an 80 percent positive rating. On the Metacritic website , which works according to a similar principle , the film achieved 64 out of 100 possible points. In both cases, the audience rating was slightly higher. The user ratings in the Internet Movie Database and the Online Movie Database are largely similar : Here the film achieved an average of 7.5 and 7.2 out of 10 possible points, respectively. (As of August 2016)

Harry Potter as a literary film adaptation

The critics unanimously emphasized the proximity to Rowling's novel. Thanks to its “letter fidelity”, Columbus managed to “flawlessly adapt literature”, which “brought film and book perfectly together”. The high degree of fidelity to the original was rated very differently: In the Daily Telegraph and the New York Post the implementation was described as a success, and a critic from Empire said, “ fans probably couldn't hope for a better adaptation ” (German: “ Fans probably can't hope for a better adaptation ”).

In contrast to this, it was for Konrad Heidkamp from the time the “decisive mistake” of the film that it hardly deviated from its original. With no room for one's own creative development, “a copy of the novel was created.” The daily newspaper also regretted that the film, despite its excess length, “only tells bullet points about what happens [in the novel].” Harald Martenstein wrote for the Tagesspiegel :

“As paradoxical as it sounds - it is precisely because of its efforts to be as close as possible to the book that the film moves away from its role model. What falls by the wayside are the retarding moments, the subtle alternation of pace and standstill in Rawlings [ sic ] prose. The narrative thread gets lost in this grandiose number revue at some point, and anyone who does not know the book will find it difficult to understand the story. The film is always full throttle so that it can manage its workload. "

And in the Berliner Zeitung, Anke Westphal added:

“In fact, the 'Potter' director Chris Columbus slavishly adhered to the external guidelines of the author Joanne K. Rowling. [...] Columbus conscientiously illustrated the book, which leads to a running time of two and a half hours, which is not insignificant even for adults. But it remains with the diligent surface work, with checking off the book chapters. 'Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone' did not become a film about the idea of the 'Potter' novels. "

On the other hand, Hanns-Georg Rodek admitted in his criticism for the world that a coherent work had been created:

“Columbus' fidelity to the letter - undoubtedly fueled by Rowling's omnipresent interference in every phase of production - goes so far as to take on the book's weaknesses. Actually, this first volume has no real narrative flow, the Hogwarts seasons and adventures are simply strung together - and Columbus does not manage this lack of rhythm either. But, and that is more important than the rhythm between scenes, Columbus finds a balance in the scenes, a harmony of mood, tricks and characterization of the characters. "

Subsequently, however, Rodek complained that the film could not stand for itself without the book and that “it is almost a matter of course that the reading was done before going to the cinema.” On the other hand, Westphal found it legitimate that the film was “completely in the service of one childlike viewer ”, which the visit to the cinema serves to“ compare [the] reading experience ”. In summary, Der Spiegel stated that the film "stumbles [...] again and again over the claim to satisfy the novel more than itself."

Several times it was regretted that only little of the atmosphere and emotional world of the novel got into its film version. For example, the USA Today review points out that Rowling's way of expressing emotions was the charm of the book, and then goes on, “ But not enough of that emotional range ends up on the screen. ”(German:“ But little of this range of feelings arrives on the screen. ”) Spiegel Online again sees a reason in the fact that the film reproduces too many details of the book:“ There is no time in the film for a character to develop. "

Acting performance

The main actor Daniel Radcliffe could only convince a few critics. While the Daily Telegraph described the portrayal of the title character as “ wonderful ”, it was often criticized as “flat” or “smooth”, while New York Magazine even certified Radcliffe a “ dull, pinched presence ” (German : "Expressionless, inadequate presence"). Many reviews identified him as a weak point in the ensemble; Katrin Hoffmann wrote for the epd film :

“Daniel Radcliffe as Harry is also the weakest link in the otherwise high-profile cast list. He plays a rather reserved, hesitant Harry, whom you immediately believe that he was always abused in the first eleven years of his life, but who cannot express the courage and shrewdness that characterize Harry in the book above all. "

Meanwhile, Heidkamp's review of the times saw an advantage in Radcliffe's cautious style of play:

"Admittedly, Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter remains [...] pale, but what you register slightly disappointed at first, becomes a condition of the film in retrospect. How unbearable he would 'play' with just a hint of cheek or complacency. [...] If Harry were sure of his (film) historical significance, he would be puke. "

Time magazine called the three young stars Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson “ competent but charisma-free ” (German: “competent, but free of charisma”). For example, Variety , which Watson found “ adorably effusive ” (German: “admirably effusive”), or New York Magazine , which Grint, in contrast to Radcliffe, considered “ marvelously expressive ” (German: “fabulously expressive”), judged differently . According to the New York Post , Grint even stole the show from lead actor Radcliffe. Meanwhile, for the New York Times Tom Felton was Harry's opponent Draco Malfoy as the film's “ show stopper ”.

The acting performance of the adult ensemble was almost without exception praised. Robbie Coltrane's portrayal of the giant Hagrid was often highlighted, in which world author Rodek "was not surprised if Rowling would at some point admit that she had modeled the character of the actor." For others, Alan Rickman was particularly noteworthy as Professor Snape; For example, CNN wrote : “ Coltrane stands out […], but Rickman steals the show. "(German:" Coltrane stands out, but Rickman puts everyone in the shade. ")

Production design and effects

The interplay between production design and effects received a lot of press recognition. The Berliner Zeitung wrote : "The scenes are magnificent, the film structures and costumes wonderful, the tricks charming - especially details like the 'talking hat' [...] are lovingly executed." Some reviews cited the action-packed Quidditch game as an example “Impressive” computer work. In contrast, for Variety it was the only scene with exaggerated CGI effects, “ as the camera moves are far too precise and measured and the backgrounds look too clean. ”(German:“ because the camera moves much too precisely and evenly and the backgrounds look too clean. ”) For the New York Times , the effects were“ mortifyingly ordinary ”(German:“ embarrassingly ordinary ”).

music

Clear rejection expressed the critic for the film music of John Williams from The loud Slant " mind-numbing, non-stop " (German: "todlangweilige, never-ending") soundtrack was for the Hollywood Reporter no more than " a great clanging, banging music box did simply will not shut up "(German:" a large, jingling, booming music box that just will not be silent "). USA Today wrote: “ [The] overly insistent score lacks subtlety and bludgeons us with crescendos. ”(German:“ [The] overly persistent music lacks sensitivity, and it bludgeons us with crescendos . ”) Variety summarized:“ Half as much music would have been more than enough, at half the volume. ”(German:“ Half as much music would have been more than enough at half volume. ”)

Awards

| Award | Category and award winner |

|---|---|

| Artios 2002 | Best Casting for Feature Film, Comedy for Jane Jenkins and Janet Hirshenson |

| BMI Award 2002 | BMI Film Music Award for John Williams |

| Critics Choice Award 2002 | Best Family Film (Live Action) |

| CDG Award 2002 | Excellence in Fantasy Costume Design for Judianna Makovsky |

| Empire Awards 2006 | Outstanding Contribution to British Cinema (for Harry Potter films 1–4) |

| Evening Standard British Film Award 2002 | Technical Achievement Award for Stuart Craig |

| Sierra Award 2002 | Best family film |

| Saturn Award 2002 | Best Costumes for Judianna Makovsky |

| Satellite Award 2002 | Outstanding New Talent Special Achievement Award for Rupert Grint |

| Young Artist Award 2002 | Best Performance in a Feature Film - Leading Young Actress for Emma Watson ; shared with Scarlett Johansson |

| Most Promising Young Newcomer for Rupert Grint |

Film awards

The film has been nominated for a large number of major film awards and has received several awards.

At the Academy Awards 2002 , the film was proposed in three categories: Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan stood for the best production design , Judianna Makovsky for the best costume design and old master John Williams for the best film music . When the prizes were awarded, the nominees received nothing in all three categories. It was also not awarded at the Grammy Awards 2003 , where Williams' film music was proposed as the best soundtrack and Hedwig's theme as the best instrumental piece.

The film received seven nominations for the British Academy Film Award 2001: for best British film , Robbie Coltrane for best supporting actor , for best visual effects , best costumes , best mask , best production design and best sound . In addition, the film adaptation of the novel was nominated the following year for the British Academy Children's Awards , a prize awarded by BAFTA to offers for children, in the category of best feature film. Again, Harry Potter could not convert any of the nominations into an award.

The Broadcast Film Critics Association honored Harry Potter with the 2001 Critics' Choice Movie Award for Best Family Film ; in the same category he was honored by the Las Vegas Film Critics Society and the Phoenix Film Critics Society . As a complete work, he was also nominated for an Amanda , a Hugo Award , a Satellite Award and a Teen Choice Award without receiving an award. After two unsuccessful nominations for the Empire Awards 2002 - for best film and for the trio Radcliffe / Grint / Watson as best newcomer - the then four-part Harry Potter film series was honored with the special Outstanding Contribution to British Cinema Award in 2006.

Out of a total of nine nominations at the Saturn Awards 2001, the film was only able to win the Best Costumes category . Costume designer Judianna Makovsky also received an award from the Costume Designers Guild . The production design was honored with an Evening Standard British Film Award , the film music with a BMI Award . The Casting Society of America presented an Artios Award for actor selection . The film was nominated for Satellite Awards in a total of five categories , but only Rupert Grint took home an award: Best New Talent. He also received a Young Artist Award in the Most Promising Young Newcomer category ; his colleague Emma Watson shared the award in the category Best Performance in a Feature Film - Leading Young Actress with Scarlett Johansson ; three further nominations did not result in an award. Daniel Radcliffe was nominated for best newcomer at the MTV Movie Awards 2002 , but could not prevail against Orlando Bloom .

Movie ratings

The German Film and Media Assessment (FBW) awarded the film the rating “valuable”.

Fan tourism at the locations

Even before the film was released, fans had begun to visit the locations specifically; after the theatrical release the phenomenon intensified. While the residents of Picket Post Close in Martins Heron reacted calmly and no tourists were allowed into Australia House for safety reasons, other places advertised their role in the film. The London Zoo drew attention to its function as a film set with a notice board and added Harry Potter items to the range of its souvenir shop. Signs were installed at King's Cross station prohibiting, for example, magic or the parking of brooms. A sign with the inscription “ Platform 9 ¾ ” (German: “Gleis 9 ¾”) was later supplemented by the installation of a trolley that apparently got stuck in the wall. A banner with the words “ Harry Potter Film shot here ” (German: “ Harry Potter Film shot here ”) in front of the main entrance to Alnwick Castle had to be removed again under pressure from Warner Bros. The UK Tourism Authority published a travel guide specifically for the filming locations shortly after the cinema release , established travel guides followed suit, and various organizers put together travel offers specifically for Harry Potter fans.

Harry Potter film series

The film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone set the starting point for an eight-part film series. After the first, the following six Harry Potter novels were also filmed; the final volume, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows , was split into two full-length films, the second of which was released in July 2011. With total box office earnings of around 7.7 billion US dollars worldwide, the Harry Potter films are considered the most successful film series ever (as of April 2012).

As the first film in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone created the basis for the other films in many ways, starting with the staff: the majority of the key characters on the film staff continued their work on the series. David Heyman was the producer of all subsequent films, the third and from the fifth he shared this task with others. Chris Columbus also directed the second film and was involved in the third as a producer. Steven Kloves wrote the scripts for all Harry Potter films with the exception of the fifth. John Williams composed the score up to and including the third part of the series. Production designer Stuart Craig and decorator Stephenie McMillan worked on all eight films. Likewise, the actors were almost without exception to be seen again in the later films. Only the role of headmaster Dumbledore was re-cast after the death of Richard Harris, from the third film Michael Gambon took over the part. All other leading and supporting roles were embodied in all eight films by the same actors. The filming of the first volume must therefore also be seen as the start of some acting careers. The young actors in particular were not previously known to a larger audience.

The Philosopher's Stone also strongly influenced its successors in several aspects of its cinematic implementation . For example, apart from the design of the book cover, the film adaptation was the first comprehensive official visualization of the Harry Potter material . For example, the appearance of school uniforms, fantastic creatures or the architecture of Hogwarts was determined for the first time. The successors followed many of these design decisions. Costumes were added and modified rather than fundamentally redesigned. Filming locations such as Alnwick Castle, the Bodleian Library and Gloucester Cathedral were used again in the later parts, the Dursleys' house was recreated in the studio. In the course of the series, however, details of the costumes, the set design and the appearance of mythical creatures were modified and refined - thanks in part to advances in the field of visual effects. In a similar way, the music of the later Harry Potter films builds on the work of John Williams, whose Hedwig theme became a theme tune for the film series. The high degree of continuity contrasts with the fact that the film series was made by four different directors, each of whom gave his Harry Potter films their own character. While the first two films that were made under Columbus' direction are still very similar to one another, the staging of the third part by director Alfonso Cuarón is perceived as a fundamental innovation.

literature

- Joanne K. Rowling : Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . Carlsen, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-551-55167-7 .

- Jeff Jensen, Daniel Fierman: Harry Potter Comes Alive . In: Entertainment Weekly . No. 614 , September 14, 2001 ( ew.com [accessed June 7, 2011]).

- Gareth McLean: In Harry Potter land . In: The Guardian . October 19, 2001, p. 2 ( guardian.co.uk [accessed June 7, 2011]).

- Jess Cagle: Cinema: The First Look At Harry . In: Time . Vol. 158, No. 20 , November 5, 2001 ( [3] ; [4] [accessed June 9, 2011]).

- Jörg C. Tile: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone; Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets . In: Andreas Friedrich (Hrsg.): Film genres: Fantasy and fairy tale film . Reclam, 2005, ISBN 3-15-018403-7 ( excerpt [accessed June 6, 2011]).

- Ricarda Strobel : Harry Potter on the screen: The film Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . In: Christine Garbe, Maik Philipp (ed.): Harry Potter - a literary and media event in the focus of interdisciplinary research . tape 1 of literature - media - reception . LIT Verlag, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-7242-4 , p. 113-127 .

- Sabine-Michaela Duttler: The cinematic implementation of the Harry Potter novels . Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8300-3314-1 .

- Andreas Thomas Necknig: How Harry Potter, Peter Pan and The Neverending Story were conjured up on the canvas. Literary and didactic aspects of film adaptations of fantastic children's and youth literature . Lang, 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55486-9 , pp. 59 .

Web links

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in the online movie database

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in the lexicon of international films

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in All Movie Guide (English)

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone atRotten Tomatoes(English)

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone at Metacritic (English)

- Comparison of the cuts in the theatrical version - US TV Extended Cut of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone at Schnittberichte.com

Remarks

- ↑ Based on the 1998 annual mean value of the British pound in US dollars: £ 0.6038 ≙ $ 1. See the external value of the pound sterling .

- ↑ The film was shot between tracks 4 and 5 because the local conditions there correspond more to Rowling's descriptions than between tracks 9 and 10. The reason for this is that Rowling, as she testified in a 2001 BBC interview, the King's Cross and Euston confused. See: What Harry does next. In: Online edition of the Daily Mail . December 24, 2001, accessed on July 29, 2011 (English): “I wrote platform 9 3/4 - or I came up with the idea-when I was living in Manchester and I wrongly visualized the platforms - I was actually thinking of Euston. "

- ↑ A detailed comparison of the seven-minute difference is provided by Schnittberichte.com under Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. Retrieved July 29, 2011 .

- ↑ Only data from some important markets are given here as examples. A more comprehensive list of visitor numbers in Europe is available from the European Audiovisual Observatory under Film Information: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . The box office results from other countries are at Box Office Mojo under Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. Box Office by Country available.

- ↑ a b Only a selection of important film awards is shown here. The Internet Movie Database has a more extensive list under Awards for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Certificate of Release for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . Voluntary self-regulation of the film industry, October 2001 (PDF; test number: 88 989 K).

- ↑ Age rating for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . Youth Media Commission .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Jeff Jensen, Daniel Fierman: Harry Potter Comes Alive . In: Entertainment Weekly . No. 614 , September 14, 2001.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Gareth McLean: In Harry Potter land . In: The Guardian . October 19, 2001, p. 2 .

- ↑ Jonathan Ross : Friday Night with Jonathan Ross, July 6, 2007, BBC One . Interview with JK Rowling. ( Transcription. In: Accio Quote. Accessed 7 June 2011 . )

- ^ A b Colleen A. Sexton: JK Rowling Biography . Twenty-First Century Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8225-7949-6 .

- ↑ a b Urs Jenny: Crash course for sorcerer's apprentices . In: Der Spiegel . No. 47 , 2001, p. 198 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Jess Cagle: Cinema: The First Look At Harry . In: Time . Vol. 158, No. 20 , November 5, 2001 ( [1] ; [2] ).

- ↑ Susanne Vieser: Profit with Potter . In: Focus Money . No. 42 , October 12, 2000 ( focus.de [accessed July 2, 2010]).

- ↑ Sheryle Bagwell: WiGBPd About Harry . In: Australian Financial Review . July 19, 2000 ( accio-quote.org [accessed June 7, 2011]).

- ↑ a b Peter Hossli: The billions hang on Potter's wand. June 7, 2007, accessed June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. In: online edition of the Guardian . November 16, 2001, accessed June 7, 2011 .

- ^ A b Brian Linder: Davis Confirms Potter Role. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . January 8, 2001, archived from the original on April 26, 2009 ; accessed on June 14, 2011 .

- ^ Paul F. Duke, Dana Harris: Spielberg opts out of 'Potter'. In: online edition of Variety . February 22, 2000, accessed June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ Guylaine Cadorette: Quote of the Day: Spielberg on not making Harry Potter. In: Hollywood.com . September 5, 2001, accessed on June 7, 2011 (English): “[…] for me, that was shooting ducks in a barrel. It's just a slam dunk. It's just like withdrawing a billion dollars and putting it into your personal bank accounts. There's no challenge. "

- ↑ Christoph Dallach: I feel like a Spice Girl . In: KulturSpiegel . No. 4/2000 , March 27, 2000, pp. 6 ( spiegel.de [accessed on July 7, 2011] Interview with JK Rowling).

- ↑ Laura Miller: Fans hate director picked for Harry Potter film. In: Salon.com . March 30, 2000, accessed June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Greg Dean Schmitz: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001). (No longer available online.) In: Yahoo .com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Chris Columbus to Direct Harry Potter. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . March 28, 2000, archived from the original on January 13, 2008 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Screenwriter Kloves Talks Harry Potter. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . February 6, 2001, archived from the original on October 19, 2007 ; accessed on February 22, 2016 (English): “It's really faithful. […] There's stuff of my own, there's dialogue of my own obviously, but it's sort of extrapolating from what Jo [Rowling] writes. "

- ↑ Michael Sragow: A wizard of Hollywood. (No longer available online.) In: Salon.com . February 24, 2000, archived from the original on August 6, 2011 ; accessed on February 22, 2016 (English): “Adapting the first book in the series is tough because the plot doesn't lend itself to adaptation as well as the next two books; Volumes 2 and 3 lay out more naturally as movies, since the plots are more compact and have more narrative drive. "

- ↑ Susie Figgis. Internet Movie Database , accessed June 10, 2015 .

- ^ A b Brian Linder: Chris Columbus Talks Potter. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . March 30, 2000, archived from the original on December 6, 2008 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Harry Potter Casting Frenzy. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . June 14, 2000, archived from the original on April 25, 2009 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Trouble Brewing with Potter Casting? In: IGN.com . July 11, 2000, accessed June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Artios Award Winners. Casting Society of America , accessed June 28, 2011 .

- ^ A b Paul Sussman: British child actor 'a splendid Harry Potter'. (No longer available online.) In: CNN. August 23, 2000, archived from the original on March 8, 2012 ; accessed on February 22, 2016 (English).

- ↑ Larry Carroll: 'Narnia' Star William Moseley Reflects On Nearly Becoming Harry Potter. In: MTV . February 5, 2008, accessed February 22, 2016 .

- ^ Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson bring Harry, Ron and Hermione to Life for Warner Bros. Pictures' "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone". (No longer available online.) In: Warner Bros. Web site August 21, 2000, archived from the original April 4, 2007 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d Martyn Palmer: When Danny met Harry . In: The Times . November 3, 2001 ( history.250x.com [accessed May 9, 2006]). When Danny met Harry ( Memento from May 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Barry Koltnow: One enchanted night at the theater, Radcliffe wurde Harry Potter. (No longer available online.) In: Online edition of the East Valley Tribune . June 6, 2007, archived from the original on October 11, 2007 ; accessed on June 7, 2011 .

- ↑ Missy Schwartz: Season of the Witch. (No longer available online.) In: Entertainment Weekly . December 14, 2001, archived from the original on December 20, 2001 ; accessed on February 22, 2016 (English, interview with Emma Watson).

- ↑ a b Jörg C. tile: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone; Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets . In: Andreas Friedrich (Hrsg.): Film genres: Fantasy and fairy tale film . Reclam , 2005.

- ↑ a b Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 114 .

- ↑ The cast and crew for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001). Internet Movie Database , accessed June 2, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c Filming Locations - Muggle Names. Retrieved June 8, 2011 .

- ↑ Connie Ann Kirk: JK Rowling: a biography . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 978-0-313-32205-1 , pp. 96 .

- ↑ a b c Magic Kingdom . In: People . Vol. 57, No. 1 , January 14, 2002, p. 132 ( people.com [accessed June 5, 2011]).

- ^ Brian Linder: Hogwarts Oxford Location Pics & Rowling Speaks. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . October 3, 2000, archived from the original on April 25, 2009 ; accessed on June 8, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Potter Set News & Pics. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . November 15, 2000, archived from the original on August 31, 2011 ; accessed on June 8, 2011 .

- ^ A b Brian Linder: Potter Pics: Hagrid, Hogsmeade Station, and the Hogwarts Express. In: IGN.com . October 2, 2000, accessed June 8, 2011 .

- ↑ Brian Linder: Potter Pics: Part Two ¿The Hogwarts Set at Durham Cathedral. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . October 3, 2000, archived from the original on October 19, 2007 ; accessed on June 8, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Why does the Harry Potter movie have a different title in England? In: Yahoo .com. January 23, 2002, accessed June 24, 2011 .

- ^ A b Philip Nel: You Say “Jelly,” I Say “Yell-O”? Harry Potter and the Transfiguration of Language . In: Lana A. Whited (Ed.): The ivory tower and Harry Potter: perspectives on a literary phenomenon . University of Missouri Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8262-1549-1 , pp. 261 ff .

- ↑ Christ Church College, St Aldate's, Oxford, Oxfordshire, England, UK. In: Find Hogwarts. Retrieved June 8, 2011 .

- ^ A b Brian Linder: Potter Creature Feature. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . January 11, 2001, archived from the original on April 26, 2009 ; accessed on June 15, 2011 .

- ^ Paul Wilson: Visual Effects / Miniature Photography . In: Barbara Baker (Ed.): Let the credits roll: interviews with film crew . McFarland, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7864-1679-0 , pp. 116 .

- ↑ Petra Ahne: The eyes too blue, the hair too straight . In: Berliner Zeitung . November 23, 2001 ( berliner-zeitung.de ).

- ↑ Ian Hart. Internet Movie Database , accessed June 10, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hanns-Georg Rodek: The magic of the familiar . In: The world . November 21, 2001 ( welt.de [accessed June 24, 2011]).

- ↑ a b c d Todd McCarthy: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone . In: Variety . November 11, 2001 ( variety.com [accessed June 24, 2011]). Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone ( Memento July 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f Kimberley Dadds, Miriam Zendle: Harry Potter: Books vs films. In: Digital Spy . June 9, 2007, accessed June 14, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c Richard Dyer: The wizard of film scoring tackles 'harry potter' . In: The Boston Globe . May 18, 2001, p. D.14 ( online [accessed June 29, 2011]). The wizard of film scoring tackles 'harry potter' ( Memento from June 10, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e Jonas Uchtmann: Short reviews - Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. In: FilmmusikWelt. May 31, 2004, accessed June 14, 2011 .

- ↑ a b John Takis: CD Review: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. (No longer available online.) In: Film Score Monthly . March 4, 2002, archived from the original on October 23, 2006 ; accessed on June 14, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Filmtracks: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (John Williams). In: Filmtracks.com . August 14, 2001, accessed June 29, 2011 .

- ↑ a b William New Year's Eve: Harry Potter Collector's Handbook . F + W Media, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-0897-3 , pp. 175 .

- ↑ Harry Potter And The Sorcerer's Stone Soundtrack CD. In: CD Universe. Retrieved June 30, 2011 .

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. In: synchronkartei.de. German synchronous index , accessed on July 7, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 116 ff .

- ↑ a b c Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 120 .

- ^ Paul VM Flesher: Being True to the Text: From Genesis to Harry Potter . In: Journal of Religion and Film . Vol. 12, No. 2 , October 2008, p. H. 2 ( unomaha.edu [accessed July 7, 2011]). Being True to the Text: From Genesis to Harry Potter ( Memento of September 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ cf. also see the section on end cut

- ↑ Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 123 f .

- ↑ Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 122 f .

- ^ "Hook meets Indiana Jones" - John Williams: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001). (No longer available online.) In: Filmmusik 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011 ; Retrieved June 30, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 125 f .

- ↑ Andreas Thomas Necknig: How Harry Potter, Peter Pan and The Neverending Story were conjured up on the canvas . 2007, p. 59 .

- ↑ a b Reinhard Bradatsch: Film review Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. (No longer available online.) In: allesfilm.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011 ; Retrieved July 7, 2011 .

- ↑ Sabine-Michaela Duttler: The cinematic implementation of the Harry Potter novels . 2007. According to Mittelbayerische.de ( Memento from August 5, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Stefanie Hundeshagen, Maik Philipp: Dirty Harry? The film characters Harry, Dobby and Hagrid in the light of an audience survey . In: Christine Garbe, Maik Philipp (ed.): Harry Potter - a literary and media event in the focus of interdisciplinary research . tape 1 . From literature - media - reception. LIT Verlag, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-7242-4 , p. 131 f., 137 .

- ↑ Andreas Thomas Necknig: How Harry Potter, Peter Pan and The Neverending Story were conjured up on the canvas . 2007, p. 58 f .

- ↑ a b c d e Anke Westphal: The brightly cleaned evil . In: Berliner Zeitung . November 21, 2001, p. 13, 15 ( berliner-zeitung.de ).

- ↑ a b Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 126 .

- ↑ Andreas Thomas Necknig: How Harry Potter, Peter Pan and The Neverending Story were conjured up on the canvas . 2007, p. 62 .

- ↑ Brian Linder: Potter Poster Pic. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . December 13, 2000, archived from the original on October 11, 2008 ; Retrieved June 24, 2011 .

- ^ Brian Linder: Potter Preview Premieres Tomorrow. (No longer available online.) In: IGN.com . February 28, 2001, archived from the original on October 19, 2007 ; accessed on June 24, 2011 .

- ↑ Potter casts spell at world première. In: Internet pages of the BBC . November 5, 2001, accessed June 24, 2011 .

- ↑ Ricarda Strobel: Harry Potter on the canvas . 2006, p. 113 .

- ↑ Most successful films: "Herr" and "Harry" in the Hall of Fame. In: Spiegel Online . March 5, 2002, accessed June 3, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. In: The Numbers. Retrieved June 28, 2011 .

- ↑ DVD & Video: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. In: moviefans.de. Retrieved June 28, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in the online movie database

- ↑ Details about the film. August 30, 2007, accessed September 13, 2012 .

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone on the British Board of Film Classification

- ↑ a b c Mood Barometer Children's Film: FSK approvals for the youngest moviegoers. Voluntary self-regulation of the film industry , accessed on June 3, 2011 .

- ↑ a b The Religious Seduction of Young Potter Fans. In: Spiegel Online . November 20, 2001, accessed June 3, 2011 .

- ↑ Harry Potter film: Churches give the all-clear. In: ORF.at . November 21, 2001, accessed June 4, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c Harald Martenstein : Harry Potter: The full droning . In: Der Tagesspiegel . November 20, 2001 ( tagesspiegel.de [accessed June 24, 2011]).

- ↑ a b c Konrad Heidkamp : Magical decals . In: The time . No. 48 , 2001 ( zeit.de [accessed June 24, 2011]).

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone . In: film service . No. 24 , 2001 ( bs-net.de [accessed July 7, 2011]).