Dark European bee

| Dark European bee | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dark European bee |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Apis mellifera mellifera | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The dark European bee ( Apis mellifera mellifera ) is a naturally occurring subspecies of the western honey bee ( Apis mellifera ). It is the only honeybee originally native to the north of the Alps and the archetype of all honeybees.

Original geographic distribution

Studies from 2013 show that the primordial honey bee ( Apis ) lived in Europe 25 million years ago. During the different phases of the Ice Age , colonies of this European primordial honeybee migrated back and forth between northern and southern Europe. During the last ice age, which ended around 11,700 years ago, the Alpine countries Switzerland and Austria were completely covered with ice. The primordial bee withdrew to southern Europe again. Around the Mediterranean Sea, where the sea level was up to 90 meters lower due to the Ice Age and where new land was created in the meantime, she found dense coastal forests and other climatically favored areas.

Development of the M group

The different zones on the Iberian Peninsula, southern France, Italy and the Balkans offered ideal conditions for the formation of isolated populations from which two groups of western honeybees ( Apis mellifera ) could develop: in Italy and in the Balkans the C group , including the Carnica and Ligustica bee. In southern France it was the M group of dark bees from northern and western Europe and North Africa.

Two subspecies developed from the M group on the European continent:

- Dark European bee ( Apis mellifera mellifera ) north of the Alps, Northern and Eastern Europe

- Iberian bee ( Apis mellifera iberica ) in Spain and Portugal

as well as in North Africa:

- Saharan bee (Apis mellifera sahariensis)

- Tell bee (Apis mellifera intermissa)

- Reef bee (Apis mellifera major)

Spread on the north side of the Alps

From the end of the Ice Age 11,700 years ago, the climate on the European continent warmed up again. The subspecies of the Iberian bee had established itself on the Iberian Peninsula (which, like the dark bee, belongs to the M group), in Italy the Ligustica bee and in the Balkans as far as Vienna the Carnica bee (both from the C group) . The newly created subspecies of the dark bee had to overcome the 1200 kilometer long and 250 kilometer wide Alpine arc in order to reach its future territory on the north side of the Alps. 9000 years ago, the dark bee spread from the French Mediterranean coast in a pincer movement around the eastern flank or the western flank of the Alps to Germany - and from there in a north-south movement into the Alpine valleys of Austria and Switzerland. The dark bee followed a "pioneer plant", the hazel . This has a speed of spread of 1.5 kilometers per year. With the “hazelnut line”, which is constantly shifting northwards, the dark bee made the 2600 kilometer route from the 42nd parallel (near Perpignan) around the Alpine arc to the 60th parallel (near Stockholm) in 1700 years.

Spread overseas

European emigrants took the dark bee with them to all temperate zones on the other continents. Around 1850 the dark bee reached its greatest distribution worldwide.

description

The dark bee differs morphologically clearly from the Carnica and Ligustica , the two most frequently kept honey bees worldwide. The description of the bee researcher Friedrich Ruttner based on exhibits and data from the period from the 19th century to the present day helps to determine this:

coloring

The dark bee differs from the other subspecies of the western honeybee by its black chitin armor and the dark brown hair on the chest (thorax). The local populations of the dark bee in Switzerland and Austria, the Apis mellifera mellifera Nigra , have black hair and pigmented wings. This gives these bees a velvety black appearance, which gave them their name (Nigra = Latin for black). Yellow colored symbols do not appear in the dark bee, small leather-brown corners on the second back plate ( tergite ) of the abdomen ( abdomen ) are possible.

Body shape and hair

Of all the subspecies of the western honey bee , the dark bee has the longest and widest body. Conversely, it has the shortest proboscis (labium) in relation to its body length . The trunk length of the dark bee is decreasing from south to north at 6.45 mm (southern France) over 6.19 mm (Alps) to 5.90 mm (Norway). The comparatively thick, black abdomen with a blunt end is striking. The dark bee wears narrow, thin felt bandages between the back plates of the abdomen. On the fifth back plate of the abdomen it has the longest overthair (0.40 to 0.50 mm) of all subspecies of the western honey bee.

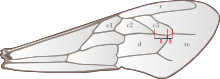

Wing veining

The dark bee has the lowest cubital index of any subspecies of the western honey bee. For the definition of the cubital index , the forewings of the workers are measured, which have fine veins with a clear division into individual cells. The veins of the third cubital cell (C3) are important for differentiation. In the dark bee this C3 cell is wide and stocky, in the Carnica it is much longer and slimmer. The returning nerve (nervus recurrens) of the C3 cell is divided into two parts. The ratio of the two lengths A and B to each other is called the wing index or cubital index. With the dark bee this ratio is always less than 2.0 (on average 1.7), with the Ligustica and Carnica it is greater than 2.0. This means that part length B can be accommodated more than twice in part length A. Further distinguishing features in the wing veins of the dark bee are a dumbbell index below 9.32 and a discoid shift in the negative range.

properties

The characteristics of a bee colony depend less on the subspecies than on the local climate and range of costumes, as well as on the decades of selection and the mode of operation of the beekeepers. Differences supposedly dependent on the subspecies do not stand up to scientific tests.

Between the 46th degree of latitude (in the Swiss Alpine valleys) and the 60th degree of latitude (near Stockholm), the climate shaped by the Atlantic is often harsh, with a changeable spring and more and more rainy summer months. The Dark bee responds and adapts colony development, breeding activity and food consumption to the local climate and foraging on. Friedrich Ruttner summarizes the properties of the Mellifera: "The dark bee shows extreme caution as a survival strategy in a harsh environment."

Gross activity

The breeding activity of the Mellifera does not begin «explosively» in spring, but is dosed and adapted to the local climate and the range of costumes. The Mellifera also "steers" towards the peak of their breeding activity in doses: at the solstice , the brood nest of the dark bee is still compact, which ensures the survival of the colony and leads to long-lived bees. Other subspecies immediately convert the honey into brood, which can then starve to death due to a lack of food.

From the British Isles to the Urals, and from the Alps to Scandinavia, the dark bee has the same genetic characteristics. But because the local climate and the range of costumes differ across Europe, local ecotypes were formed . In south-west France, for example, in the Les Landes department, the heather, the most important herbaceous plant, does not bloom until July to the end of August. The local ecotype there therefore begins its breeding activity at the end of April at the earliest. In the region around Paris, on the other hand, the first fruit trees bloom as early as March, and the costume ends at the beginning of July with the sweet chestnut. With this typical Central European early forage, the local ecotype begins its breeding activity as early as February.

Brood nest

The compact brood nest of the Mellifera is surrounded by a wide wreath of pollen and above it a heavy wreath of honey . In contrast to the other subspecies, the dark bees even store the pollen under the brood nest. Such a proximity of brood and supplies is typical for the "Hüngler type" among honey bees, that is, for colonies that limit their breeding activity when there is a lack of food so that they do not have to go hungry.

Honey performance

Comparative studies from the 1960s show that with normal mass forage, the average honey production of Mellifera colonies was 20 percent lower than that of Carnica colonies. In critical foraging conditions, however, the average honey production of the Mellifera was greater than that of the Carnica. The reason for this discrepancy is that the Carnica queens came from breeding stocks with drone-safe mating sites as early as the 1960s, but the Mellifera has only been bred under controlled conditions since the 1990s. In critical foraging conditions, however, the dark bee is superior to other subspecies because it can react to the changeable Atlantic climate on the north side of the Alps. With this property, the dark bee brings the same honey yield as other subspecies over the long term and across all colonies of different apiaries in a region.

Pollen collecting instinct

A high-performance Mellifera colony collects up to 30 kg of pollen annually in the main costume. The protein-rich pollen is stored in a wide pollen wreath as food for the larvae directly around the compact brood nest and preserved with nectar and enzymes. The dark bee has a large supply of pollen even in persistent bad weather conditions. With the dark bee's strong pollen foraging instinct, the beekeeper can remove up to 30 percent of the pollen during the main foraging. Dried bee pollen or frozen fresh pollen are offered as dietary supplements with therapeutic effects.

A side effect of the strong pollen collecting drive is the pollen-rich, very aromatic honey of the dark bee with a particularly balanced taste.

Propolis collecting instinct

The dark bee collects a lot of propolis and cemented even the smallest cracks inside the hive. Up to 250 grams of propolis per colony and year are not uncommon, which is up to three times more than the other subspecies. The beekeeper harvests the propolis with a special, fine-meshed plastic grid, the interfering spaces of which the honeybees diligently cement. The raw material obtained in this way is dissolved in 70 to 75 percent alcohol and filtered. Propolis tinctures or oils are used because of their antibiotic, antiviral and antifungal effects against infections and diseases in the mouth and airways. Propolis is a medicinal product that requires authorization and cannot be sold without authorization.

Tendency to swarm

Depending on the local climate and the range of costumes, the dosed breeding activity is associated with a low swarming instinct of the Mellifera people, who concentrate their resources on the survival of the existing people. This has the advantage for the beekeeper that the honey harvest of the dark bee is larger in weather-critical years than with other subspecies.

Winter hardiness

During wintering, the Mellifera colony is numerically strong, but the winter cluster formed by the bee colony is smaller than that of other subspecies. The dark bees sit extremely close to one another so that they can keep the warmth in the winter cluster. They usually keep an extended breeding break. This protects the winter bees, which is why the Mellifera people also start the spring with a large amount of winter. The bee researchers Gottfried Götze and Enoch Zander overwintered their Mellifera colonies “without any sugar feeding, only on the late forest honey, without any adverse consequences”. Forest honey from the sugary excretions ( melezitosis ) of plant lice on conifers crystallizes in the honeycomb cells and can then no longer be used by most honeybees subspecies. With these subspecies, a strong population loss occurs as soon as the melezitose content in the honey of a hibernating colony exceeds 10 percent.

displacement

From the second half of the 19th century, the dark honey bee was partially crossed by the importation of southern and eastern breeds. In some places, the increased stinging appetite among the hybrids led to a complete redirection (here: conversion of the bee species) of entire areas, mostly to the introduced Carinthian bee (Carnica) . This led to their displacement in many regions of their original range.

Geographical distribution today

In most European countries, if the dark bee could survive at all, there are only small Mellifera populations left. These include Great Britain, France, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland. Only on the edges of Europe, in Ireland and Russia, do large Mellifera populations ensure the existence of the native honeybees north of the Alps.

In Switzerland today there are around 15,000 pure-bred colonies of the dark bee, which corresponds to ten percent of the total number of colonies in Switzerland.

In Austria today there are around 1000 pure-bred colonies of the dark bee, which corresponds to one percent of the total number of colonies in Austria.

In Germany, after the last Mellifera population disappeared in 1975 in the small town of Suhl on the southern slope of the Thuringian Forest, the dark bee is considered to be extinct. For several years, however, several organizations have been working independently of one another to relocate the Mellifera in Germany.

Protection and Conservation Organizations

The International Association for the Protection of the Dark European Bee ( SICAMM ) is an association of all Mellifera breeding associations in Europe.

In Switzerland, the dark bee is sponsored by the mellifera.ch association.

In Austria, the dark bee is sponsored by the Association of Breeders of Dark Bees in Austria (AMZ).

In Germany there are several initiatives that are committed to protecting dark bees. See also under web links. In 2004, the German Society for the Preservation of Old and Endangered Domestic Animal Breeds (GEH) declared the dark bee “Endangered Livestock Breed of the Year”.

Protected areas

With effect from January 1, 2014, the Scottish Inner Hebridean Islands of Colonsay in connection with Oronsay were established as a reserve for the European dark bee; about 50 peoples live there. The keeping of other honey bee breeds is prohibited by law in order to protect the purebred. In addition, neither bee diseases such as nosemosis or foulbrood nor the varroa mite occur there. In Germany, there are currently the "Karwendel" locations in the Riss Valley and Nordstrandischmoor . In Austria , the "Schüttachgraben S6" and "Schwabalm S2" stations are operated in the Salzburg region. The dark bee could keep well in the Swiss foothills and Alps. There are currently 27 locations.

See also

literature

- Leon Bornus et al. a .: Encyklopedia Pszczelarza . Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Lesne, 1989, ISBN 83-09-01291-8

- Kai Engfer: The Dark Bee . Self-published, 2013 (e-book)

- Peter Mossbeckhofer: Autochthonous bee breeds in Austria at the Biodiversity in Austria symposium, June 28, 2007, 25–27

- Friedrich Ruttner: Natural history of honey bees . Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-440-09125-2

- Friedrich Ruttner, Eric Milner, John E. Dews: The Dark European Honey Bee . British Isles Bee Breeders Association, ISBN 0-905369-08-4

Web links

Germany

- Association for the Preservation of the Dark Bee eV (GEDB)

- State Association of Dark Bees Saxony eV

- Northern bee

- Breeding Association of Dark Bees Germany eV

Austria

Switzerland

International

- Societas Internationalis pro Conservatione Apis Mellifera Mellifera (SICAMM)

- Belgium: Organization de l'association Mellifica (Mellifica)

- Great Britain: Bringing Back Black Bees (B4 Project)

- Ireland: The Native Irish Honey Bee Society (NIHBS)

- Norway: Norsk Brunbielag (NBBL)

- Russia: Russian Association for Conservation Apis mellifera mellifera (RACAMM)

- Sweden: Föreningen och projects NordBi (NordBi)

- Czech Republic: Vcelatmava, Spolek chovatelů včely tmavé

Individual evidence

- ↑ Friedrich Ruttner: Natural history of honey bees. Franckh Kosmos Publishing House. 1992, p. 39

- ↑ Ulrich Kotthoff, Torsten Wappler, Michael S. Engel: Greater past disparity and diversity hints at ancient migrations of European honey bee lineages into Africa and Asia. In: Journal of Biogeography. June 20, 2013. Wiley Online Library. From OnlineLibrary.Wiley.com, accessed September 5, 2019, doi: 10.1111 / jbi.12151 .

- ↑ Friedrich Ruttner: Natural history of honey bees. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 978-3-440-09125-8 , p. 48.

- ↑ Jürg Vollmer: Description of the dark bee: color, body shape and wings. In: mellifera.ch, September 12, 2016

- ↑ Friedrich Ruttner: Natural history of honey bees. Franckh Kosmos Publishing House. 1992. pp. 62-63

- ↑ Overview of European bee breeds. In: Deutsches Bienenjournal 2/2006, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Friedrich Ruttner: Natural history of honey bees. Franckh Kosmos Publishing House. 1992, p. 55

- ↑ Jürg Vollmer: The dark bee is robust, economical and has a strong flying ability. In: mellifera.ch, September 26, 2016

- ↑ Martina Siller: Inventory of the dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) in Austria. Institute for Animal Science (NUWI), BOKU University for Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna 2010.

- ^ Reto Soland: History of the Swiss Mellifera Breeding. In: mellifera.ch magazine. August 2012, p. 14 (PDF; 4.31 MB).

- ↑ Jürg Vollmer: The dark bee diligently collects honey, pollen and propolis. In: mellifera.ch. October 10, 2016.

- ↑ How is bee pollen harvested. Swiss Pollen Beekeeping Association , accessed on October 9, 2016

- ↑ Brother Adam: Breeding the honey bee. Beekeeping Technology Verlag, Oppenau 1978, p. 54

- ↑ Josef Gstrein: The dark Tyrolean bee, a breed with special characteristics. Agricultural State College LLA Imst 2005.

- ↑ Gottfried Goetze: Beekeeping Züchterpraxis. Landbuch-Verlag, Hanover 1949.

- ↑ Jürg Vollmer: SICAMM conference 2016: International cooperation for the dark bee. In: mellifera.ch, October 24, 2016

- ↑ Societas Internationalis pro Conservatione Apis mellifera mellifera (SICAMM)

- ↑ The Endangered Livestock Breeds of 2004: The Leutstetten Horse and the Dark Bees ( Memento from August 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ilona Amos: Colonsay and Oronsay to become honeybee havens , in: The Scotsman. Scotland on Sunday , September 8, 2013, accessed September 8, 2014.

- ↑ Eric McArthur: Independent beekeepers , in: Deutsches Bienen-Journal 9/2014, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Balser Fried: Bee races and protected areas in Switzerland. ( Memento of the original from September 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Swiss bee newspaper. No. 10, 2014. pp. 12-17.