Ironworks Prince Rudolph

| Aktiengesellschaft Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | Corporation |

| founding | 1842 |

| resolution | 1978 |

| Reason for dissolution | Merger to form Salzgitter Maschinen und Anlagen AG |

| Seat |

Dülmen Germany |

| Branch | mechanical engineering |

The Aktiengesellschaft Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph (EPR) was a mining industry company founded in 1842 in Dülmen in the Münsterland region and for over a hundred years a well-known manufacturer of special machines for mines and smelting works such as steam-powered conveyors , reels and pumps . Some of their historical machines are preserved as witnesses of the industrial culture in the Ruhr area . As part of Hazemag & EPR GmbH, the company is majority owned by the Chinese Sinoma International Engineering Co., Ltd.

history

Ironworks Union of Prince Rudolph

In 1832, the entrepreneur Friedrich Beisenherz from Bochum received the right to speculate about the mining of lawn iron ore for the Dülmen, Haltern, Olfen and Lembeck area . Around the same time, Duke Alfred von Croÿ of France moved back to his ancestral home, the County of Dülmen. On April 5, 1842, Alfred von Croÿ founded the mining trade union Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph together with Friedrich Beisenherz, the domain councilors Ludwig von Noël and Rudolf Froning from Dülmen, the merchant Wilhelm von Hövel from Dortmund and two other donors from Hövel and Herdecke . The purpose of the company named after Rudolf von Croÿ was to smelt iron from the existing turf ore with the help of charcoal . On June 18, 1842 the foundation stone was laid for the ironworks of the same name in the Dülmener Feldmark, and with it the beginning of industrialization in Dülmen. A year later, in a cartel with the neighboring companies Gutehoffnungshütte (Sterkrade), Friedrich-Wilhelms-Hütte (Troisdorf) and Westfaliahütte (Lünen), shopping areas for charcoal were agreed in order to prevent price increases. In 1844 a machine factory was attached to the hut to manufacture conveying and dewatering machines for the mining industry. After 41 families moved from the Hunsrück in 1849, 275 workers were employed at the ironworks and produced 120 tons of iron worth 90,000 thalers . Almost a fifth (18.5 percent) of the population in Dülmen was dependent on wages from Prince Rudolph's ironworks at the time. In 1851 another machine factory for the manufacture of pumps and hoisting machines was attached. Starting in 1864, the first steam hoisting machines, which were trend-setting for several decades, were built, some of which were in operation until 1954.

Aktiengesellschaft Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph

After the new commercial law of 1869 came into force, the shareholders converted the union into a stock company on July 8, 1870 . At the same time, the charcoal blast furnace for iron smelting was exchanged for a modern coke blast furnace. Economically difficult years followed. With the closure of the blast furnaces in 1875, the EPR changed into a purely iron processing company with an iron foundry for machine casting and mechanical engineering. The pig iron and steel required were then bought in the Ruhr area and melted down in the smelter for further processing in cupola furnaces . In addition to the mining machines, a sample book from 1880 also offered stoves, cookware, garden furniture and railings.

On June 12, 1884, the Imperial Patent Office granted the Eisenhütte Aktiengesellschaft Prince Rudolph the first of a series of patents . In 1886 the EPR shareholders decided to reduce the share capital and convert the 310 ordinary shares into 200 priority shares .

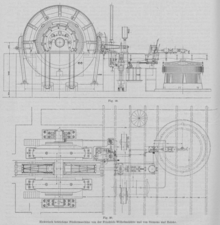

In 1890 EPR built the first compressed air piston reel . Around the same time, the works director of the Gneisenau colliery , Eugen Tomson , developed the concept of a standing composite hoisting machine with valve control, which was suitable for depths of up to 1200 m , in addition to the Tomson-Bock , and received the German Reich Patent No. 87710. From one Subsequently announced competition for the production of these hoisting machines among well-known manufacturers, the EPR emerged as the winner. The first two of these standing hoisting machines, Patent Tomson , came into use from 1896 in the Prussia II and I collieries of the Harpener Bergbau-Aktiengesellschaft . The latter was previously exhibited at the 1902 industrial and commercial exhibition in Düsseldorf and contributed significantly to the economic success of the EPR in the following years.

During the First World War , EPR mainly produced bullet cases for the war economy and only occasionally machines. From 1918, the original production could quickly be resumed. In 1921 the Recklinghausen trade union King Ludwig took over the ironworks Prince Rudolph by purchasing all shares. As a result, the company was focused purely on the production of mining machines by the new owner. For this purpose, the share capital was almost doubled to 4.0 million gold marks by 1922 and the workforce increased to 270, while the Potterie casting and the construction of agricultural machinery were stopped. Under the pressure of the global economic crisis , the trade unions King Ludwig and Ewald merged on June 21, 1935 to form the Aktiengesellschaft Bergbau AG Ewald-König Ludwig , based in Herten . The chairman of the supervisory board of the associated EPR was taken over by mine director Hellmut Reimann, the board of directors was smelting director Hans Quartier. In 1938 EPR took over the winding machine program of the Isselburger Hütte , which from then on only produced engines for the Wehrmacht as part of Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz AG .

From 1937 the ironworks Prinz Rudolph was affiliated to the Reichswerke-Hermann-Göring . The company was classified as essential to the war effort and, in addition to equipment for mining, also produced submarine covers during World War II . From 1943 onwards, 128 Dutch, Belgian and mostly Polish forced laborers were used at the EPR . For this purpose, there was a civil labor camp not far from the hut . The camp and hut were destroyed during the bombing raid on Dülmen on the night of March 21-22, 1945. Almost all documents on the ironworks Prince Rudolph were lost.

The reconstruction of the ironworks Prinz Rudolph began immediately and in June 1945 production was resumed with 70 employees. The molding shop and foundry had been in operation again since the winter of 1946 and the 1,000th large cylinder was cast in a ceremony. In 1947, the EPR built the first electric hoisting machines for the Ewald and Blumenthal collieries and, from 1950, twin steam hoisting machines , which were the most powerful in the world with 9000 HP and 200 t boom pressure. From 1955 the machine park was renewed and in 1957 the ruins of the blast furnace were torn down. In the run-up to the coal crisis , the representatives of the Ruhr coal mining industry met with Federal Minister of Economics Ludwig Erhard on October 1, 1957 , at which the EPR supervisory board chairman Hellmut Reimann was also present. In the same year a new design office was set up at EPR and a large boring mill was built in 1960. Until then, the apparatus construction was further expanded and with the start of the production of units for metallurgical plants and rolling mills, the process engineering division was established. The closure of the foundry followed in 1963. In 1967, the production of patented been lagging mats for the shoring of mines added.

On the basis of the "Law for the Adaptation and Recovery of German Hard Coal Mining and the German Hard Coal Regions" (Coal Act), a number of mining companies together with the Federal Republic of Germany founded Ruhrkohle AG (RAG) as a future total company for Ruhr mining. When the basic contract was signed on July 18, 1969, the Prinz Rudolph ironworks also became part of the state-owned Ruhrkohle AG. In 1971 a new administration building was built at the Dülmen site.

Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph Branch of Salzgitter Maschinen AG

As part of restructuring within the state-owned companies in the coal and steel industry, EPR was taken over by Salzgitter AG in 1972 and in 1974 took over 74% of Salzgitter-Cortix Industrie- und Bergbautechnik Vertriebs GmbH. On October 1, 1975, Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph AG and Salzgitter Maschinen Aktiengesellschaft (SMG) were merged and on October 1, 1977, they were merged with Salzgitter Stahlbau AG (SASTA) to form the new Salzgitter Maschinen und Anlagen AG . A new assembly hall was built around the same time. After the new name was changed to Salzgitter Maschinen AG (SMAG) in the early 1980s, the ironworks operated under the name Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph, a branch of Salzgitter Maschinen AG . From 1980 to 1982 the company built its first large complete mine in Germany in Dülmen.

Hazemag & EPR GmbH

At the end of the 20th century, Hazemag Dr. E. Andreas GmbH & Co, based in Münster, is a manufacturer of crusher systems , impact mills and rotor mills, a world-renowned company for shredding systems for the industrial processing of primary and secondary raw materials . The company founded in 1946 by Ehrhardt Andreas and Richard Rendemann owed its rise to the necessary debris removal during the reconstruction after the war and has belonged to Salzgitter Maschinenbau GmbH since 1988.

In 1989 Preussag took over Salzgitter AG and, after extensive restructuring, separated from it again in 1998. This represented one of the largest mergers of the post-war period and also affected the Prince Rudolph ironworks. In the course of the subsequent reorganization, Hazemag was merged with EPR and relocated to the location of the Prinz Rudolph ironworks in Dülmen, which in turn was taken over by Noell Service- und Maschinentechnik GmbH , which belongs to the group . In 1999, the entire Dülmen location was finally handed over to Schmidt, Kranz & Co. GmbH in Velbert and incorporated into the SG Group as the new Hazemag & EPR GmbH.

In 2006 the company bought the Mineral Processing division from DBT GmbH in Lünen . From 2008 Hazemag & EPR built one of the largest rubble recycling plants in the world for Emirates Recycling LLC in Dubai . In 2013 the Chinese Sinoma International Engineering Co., Ltd acquired 29.55% company shares of Hazemag & EPR and took over a majority stake of 59.09% by 2015.

Companies

The ironworks Prinz Rudolph was a non-listed stock corporation from 1870 to 1978. A brochure from 1890 lists the following products, among others: hoisting machines, conveyor reels, hydraulic motors, dewatering machines, water column machines, air compression machines, equipment for smelters, rolling mills, cranes, roll stands, operating machines: steam pumps, roller pulling machines, blowers, steam elevators, shredding machines, tube preheaters , Boilers, bowls, pans and retorts for the chemical and metallurgical industry, clay and sand castings of larger dimensions, forged pieces in hammer iron, Bessemer and Martin steel, also agricultural machines: plows, beet cutters, pumps, potato digging machines, threshing machines, horse stables and crockery storage facilities as well Piglet troughs.

Some of their machines were among the most modern and largest of their time and were described in technical books. They were among the last and last operated machines of their kind and are preserved as contemporary witnesses of industrial culture in the Ruhr area and are described in historical literature. Occasionally they are under monument protection .

Today Hazemag & EPR GmbH produces and sells primarily components of tunneling equipment , Drilling and crushers and mills brands Turmag, host and Salzgitter . The mining machines are mainly supplied to Eastern Europe, Russia and China. There are also licensees in Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and India.

Historical traces

- Dülmen, Brokweg: Historic workshop from 1842

- Ewald Colliery Shaft 1: Steam hoisting machine No. 922

- Ewald colliery Continuation of shaft 5: Steam hoisting machine and drive wheel from 1929 - from 1985 a memorial in front of the town hall in Erkenschwick

- Zeche Schlägel & Eisen Schacht 5 today Museum machine hall Zeche Scherlebeck : Last and probably oldest tandem steam winder in Westphalia from 1900 (No. 623).

- Zeche Schlägel & Eisen Schacht 3: Steam hoisting machine from 1926, listed as a historical monument.

- Waltrop Colliery Shaft 1: Two Zwillingstandem steam hoisting machines (No. 747 and No. 748) from 1906. Was the oldest steam hoisting machine still in operation when the colliery was closed in 1979.

- Louise pit "Carnall": Steam hoisting machine from 1915. Operational under steam for museum purposes.

- Westerholt Colliery Shaft 2: Electric hoisting machine from 1961, listed as a historical monument.

- Anna mine I main shaft, eastern production: twin steam hoisting machine from 1935

- Colliery Bergmannsglück Shaft 2: twin steam hoisting machine from 1911 with associated traction sheave and depth indicator

- Lohberg colliery : depth indicator from 1928.

- Glückauf Sondershausen Potash Plant Shaft 1: Driving wheel from 1927

- Nachtigall colliery (Witten) : Two-cylinder composite steam engine from 1887 taken over from the Franz Haniel colliery

- Radbod mine shaft 2: twin tandem hoisting machine from 1908

- Recklinghausen II mine shaft 4: Two single-stage twin counterpressure steam conveyors from 1964 No. 10038 and 1967 with the associated traction sheave and depth indicator. The last ones built for German mining.

Trivia

Ten employees of the Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph built themselves a house in 1950 as the Eisenhütte settlement group not far from the company premises at An der Silberwiese. In return for a building cost subsidy from the employer of 2500 DM, each settler had to take in another EPR employee and family as a so-called hirel .

Web links

- HAZEMAG & EPR GmbH website

- Sample book of the ironworks union Prince Rudolph (approx. 1880) University and State Library of Münster

literature

- Wilhelm Kreutzer, From the history of the ironworks Prince Rudolph: From the founding of the ironworks to its destruction in 1945 , in: Dülmener Heimatblätter 1960, issue 4, pp. 59–65.

- Bernhard Schladitz, Die Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph, global partner for coal and energy from 1961 to 1981 , in: Dülmener Heimatblätter 1982, issue 1/2, pp. 13–24.

- Hans Siebenmorgen, Die Aktiengesellschaft Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph , Diss. Cologne, 1927.

Individual evidence

- ^ Günter Brakelmann: On the trail of contemporary church history . LIT Verlag, Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-8258-1526-4 , pp. 183 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Manfred Rasch, Dietmar Bleidick, Wolfhard Weber: History of technology in the Ruhr area . Klartext-Verlag, 2004, p. 567 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Inventory: Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph 1842, 1865, 1911-1979 . Dülmen City Archives, 1982 ( nrw.de ).

- ^ Prince Rudolph ironworks. City of Dülmen, accessed December 9, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Albert Gieseler: Eisenhütte Prinz Rudolph. In: Power and Steam Engines. Retrieved December 10, 2017 .

- ^ LWL Institute for Westphalian Regional History : Westphalian Research, Volume 49 . Aschendorff, Münster 2000, p. 108–112 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Patent research at DepatisNet

- ^ The mining and smelting machines at the Düsseldorf exhibition. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 317, 1902, pp. 376-386.

- ↑ Erik Potthoff, Dietmar Rabich and Wolfgang Werp: 700 years of Dülmen . Ed .: Heimatverein Dülmen e. V. 2011 ( heimatverein-duelmen.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Martin Weinmann: List of companies that profited from forced labor during National Socialism . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 168 ( ns-in-ka.de [PDF]).

- ^ Prince Rudolph ironworks. In: City Archives. City of Dülmen, accessed on December 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Hans Rudolf Schlieker: Diary entries from the end of the war in 1945. In: Dülmener Heimatblätter Heft 1, 2005. Heimatverein Dülmen e. V., accessed December 19, 2017 .

- ^ Werner Abelshauser: Coal and market economy . In: Institute for Contemporary History (Ed.): Quarterly Books for Contemporary History 33/3 . 1985, p. 42 ff . ( ifz-muenchen.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Inventory 131 Ruhrkohle AG, Essen. In: Bergbauarchiv Bochum. Retrieved December 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Federal Minister of Finance: Capital injections into federal investments . In: German Bundestag - 8th electoral period (ed.): Drucksache 8/340133/3 . December 20, 1979, p. 14 ( bundestag.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Rolf Czauderna, Lothar Heubaum: The Anton Raky AG. Retrieved December 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b HAZEMAG & EPR celebrations for 60 years. In: International Mining. May 7, 2008, accessed December 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Bruno Peter Hennek: Noell Chronicle from 1824 to 2006 . ( hennek-homepage.de ).

- ↑ Hazemag & EPR are independent again . In: Stones + Earth . No. 2/00 , 2000 ( steine-und-erden.net ).

- ↑ Katherine Guenioui: Sinoma acquires Hazemag. In: World Cement. September 3, 2015, accessed December 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Chinese join Hazemag. In: Georesourcesnt. September 5, 2013, accessed December 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Hazemag builds rubble recycling plant for Emirates Recycling LLC. In: International Mining. February 18, 2008, accessed December 18, 2017 .

- ^ Wilhelm Müller, Engineer Stach, Bergassessor Baum: Extraction work, dewatering: IV . New edition 2014 edition. Springer-Verlag, 1902, ISBN 3-642-92017-9 , pp. 154 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Fritz Schmidt, Ernst Förster: The shaft hoisting machines . New edition 2013 edition. Springer-Verlag, 1927, ISBN 3-662-34591-9 , p. 83 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d e f 16 Westphalian mining route. In: Route Industrial Culture. Regional Association Ruhr, accessed on December 13, 2017 .

- ↑ a b 60 years of HAZEMAG, 165 years of EPR . In: Stones + Earth . No. 4/08 , 2008, p. 376-386 ( steine-und-erden.net ).

- ↑ a b c d e Wolfgang Schubert: Steam conveyors. In: The history of the minister Achenbach colliery. Retrieved December 9, 2017 .

- ^ Machine hall Scherlebeck - Shaft V / VI , accessed on September 9, 2019.

- ^ Albert Gieseler: Colliery Waltrop. In: Power and Steam Engines. Retrieved December 19, 2017 .

- ^ Albert Gieseler: Skansen Górniczy Królowa Luiza. In: Power and Steam Engines. Retrieved December 19, 2017 .

- ^ City of Gelsenkirchen Building Regulations and Building Management (ed.): Continuation of the list of monuments: Westerholt mine of the Lippe mine . May 24, 2016 ( neue-zeche-westerholt.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Walter Buschmann: Collieries and coking plants in the Rhenish coal field. Aachen district and western Ruhr area. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-7861-1963-5 , p. 167–215 ( rheinische-industriekultur.de ).

- ↑ Day of the open monument to the luck of the miners. In: Program Booklet Day of the Open Monument 2017. August 30, 2017, accessed on December 15, 2017 .

- ^ Walter Buschmann: Lohberg colliery. In: Rhenish industrial culture. Rheinische Industriekultur eV, accessed on December 18, 2017 .

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Schmidt: The history of the trade union "Glück auf" Sondershausen (1893 to 1926) . Ed .: Miners' Association "Glück auf" Sondershausen. 2005, p. 17 ( sondershausen.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Former Radbod colliery. City of Hamm, August 27, 2016, accessed December 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Twin steam conveyor of the former Recklinghausen II colliery. In: Machine Museum Bad Driburg. Retrieved December 10, 2017 .

- ^ Recklinghausen II colliery. In: Route industrial culture. Regional Association Ruhr, accessed on December 13, 2017 .

- ↑ 60 years of the Ironworks Community. In: Streiflichter. May 18, 2011, accessed December 19, 2017 .

Coordinates: 51 ° 49 ′ 33.6 ″ N , 7 ° 16 ′ 9.8 ″ E