History of the Post

The history of the post deals with one aspect of the history of communication and describes the development of a correspondence that is accessible to the general public.

A prerequisite for a reliable exchange of messages was the invention of writing and a portable writing medium . Even in pre-antiquity and antiquity there were the first approaches to an orderly news system, mainly for state-political or military purposes .

Modern postal history begins in the early modern period with the introduction of the relay system with riders and horses changing for faster communication and opening up to the general public.

This article provides an overview of the origins of written communications and the postal system from the early modern period.

Written communication in ancient times

The beginnings in Egypt and Babylonia

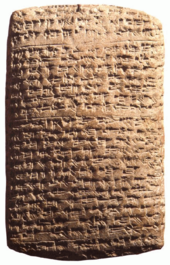

The first approaches to a regulated exchange of messages were in ancient Egypt , Babylonia and Mari (Mari letters).

The ancient Egyptians used the Nile as a main artery to carry written messages through ship travelers. The Egyptian kings also maintained contact with far-flung provinces with numerous foot messengers. These had to be able to cover long distances in the shortest possible time. In contrast, an orderly postal system in the modern sense did not yet exist in ancient Egypt.

It was not until the New Kingdom that there were official mail carriers, both footmen and riding mail carriers. Likewise, from Hittite , Ugarite and Egyptian sources, especially the Amarna letters, a lively exchange of news with the neighboring empires and the vassal states is known. According to documents from the craftsmen's settlement of Deir el-Medina , the intra-Egyptian communication was in the hands of the police.

The use of carrier pigeons for the delivery of letters, which is often claimed in postal history literature, is, however, historically controversial. Four pigeons were sent as messengers at the coronation of a pharaoh or at the Minfest , but this could not yet be described as regulated pigeon mail . The actual pigeon mail was probably not introduced into Egypt until the Roman or early Islamic period.

The Hibe papyrus , which dates from around 255 BC, provides a great deal of information about the carriage of letters in late Ptolemaic Egypt under Greek rulers . Is to be set. This document was a kind of control book of a mail carrier, in which every delivery of letters was confirmed by the recipient . The papyrus gives details about the mail delivery at that time, the addressees and the recipients. The papyrus begins with the following words:

- “On the 16th, NN gave Alexandros six items, namely: a parcel of letters to King Ptolemy, a parcel of letters to Finance Minister Apollomios and two letters attached to the parcel, a parcel of letters to Antiochus of Crete, a parcel of letters to Mendoros, to Chelos a package of letters united with the others. Alexandros handed the things over to Nicodemus on the 17th ... «

In the 1st century BC Diodorus Siculus wrote : “As soon as (the king) got up at daybreak, he first had to receive the letters coming in from all sides himself, so that he could arrange and handle everything all the more wisely after he had seen everything that had happened in the kingdom was, had fully experienced ".

Persia

In the Persian Empire , Cyrus the Great (550-529 BC) set up his own system of communication, in which mainly mounted messengers were employed. Cyrus had his own relay stations set up at regular intervals on the most important traffic routes. They were about a horse's day's journey away and served as intermediate stops for the messengers.

Herodotus (approx. 484-424 BC) reported in his Histories (VIII, 98) of the Persian Angareion, mounted messengers who carried letters in wind and weather between fixed stations, which were usually set up a day's journey from one another delivered the message to the next messenger. Xenophon also reports on this facility . Diodorus described a similar institution under Antigonus in what is now Palestine.

There were also Persian call posts after Diodorus. Over a distance of up to 30 day trips, residents were posted at intervals with strong voices shouting the news from place to place. The Persian communication system with relay stations was soon imitated by other high cultures .

Greece and Roman Empire

In Greece , in the numerous, z. Partly divided city-states do not initially have their own postal system. There were only a few foot messengers used to deliver news. These hemerodromes, called “day runners” (that's the literal translation), turned out to be faster than the messengers on horseback because of the geographic nature of Greece .

The most famous of these messengers is undoubtedly Pheidippides , who, according to tradition, Herodotus in 490 BC. BC ran in two days from Athens to Sparta (approx. 240 km) to ask for help there for the upcoming battle of Marathon . However, Pheidippides only delivered an oral message. In contrast, there was evidence of a distinct postal system among the Ptolemaic rulers of Greek origin in Egypt.

The foundations for a separate state post in the Roman Empire were laid by Gaius Iulius Caesar . The Roman Emperor Augustus later expanded it considerably. The "Post" was then called cursus publicus and was directly subordinate to the emperor. The cursus publicus was not approved for private broadcasts. As far as possible, mail was carried by ship . On land the horse was used. Separate post and rest stations, called Mansio , were set up for changing horses at intervals of around 7 to 14 km . With the fall of the Western Roman Empire , the cursus publicus also disappeared . In the Eastern Roman Empire it lasted until around 520.

For private letters you had to choose other ways: you gave them to traveling friends. However, this sometimes involved a long wait; for example, Augustine once did not receive a letter for nine years. If the distances were not that great, a Roman sent a specially kept slave who walked up to 75 km a day.

Empire of China

In Imperial China letters were already in a very distant past, pre-Christian times by state bestallte couriers transported, which, depending on the distance to be traveled route, on foot or on horseback , the delivery of first names. The foundation stone for this was laid during the Zhou dynasty (1122-256 BC). At that time, 80 messengers and 8 main couriers were subordinate to the management, for whom catering quarters were set up at intervals of about 5 km and overnight quarters at longer intervals. This system was decisively expanded during the time of the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BC) and especially during the Han Dynasty. The relay stations provided the couriers with board and lodging at state expense and looked after or replaced the horses. The heads of these stations received full tax exemption from the state in return for their efforts. In the Ming Dynasty , the postal service was under the Ministry of War .

At the time of the Middle Ages

Development in Europe

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire , there was only a reduced transmission of communications in Europe. Supraregional institutions were the Catholic Church with the missionary monks such as Bonifatius and the great Carolingian empire, which was networked with the help of messengers. However , there was no evidence to support the claim that Charlemagne (768–814) had horse relays.

In the High Middle Ages , communication in Europe was dominated by three institutions: the Catholic Church, the rulers in the various countries and European long-distance trade.

The central control of the Church in Rome (or 1309-1378 in Avignon ) and the frequent elections of the Pope forced constant correspondence with the dioceses. This also included the involvement of the monasteries, which had their own messenger services. The German-Roman rulers and kings in France and England also needed centralized communication in their countries. As a rule, however, they only use footmen, who sometimes also use rental horses from hostels on travel routes or river boats.

In the late Middle Ages, long-distance trade developed in European cities such as Antwerp, Augsburg, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Leipzig, the Hanseatic cities such as Hamburg, Bremen or Lübeck, the Teutonic Order , London, Marseille, Novgorod and the Republic of Venice , combined with a lively correspondence transnational merchant mail. In the 15th century, large banking and trading houses emerged in Italy, the Holy Roman Empire and the Netherlands. The centers were Florence, Milan, Rome, Venice, Augsburg, Brussels and Antwerp. These houses were networked with one another.

There was hardly any private correspondence in the Middle Ages. Parchment was expensive. Only the introduction of cheap paper in the 15th century led to a growing correspondence. Market ships on rivers also transported documents. Butchers took over the exchange of letters in many regions of Germany . Universities also ran messenger services, for example in Paris. The urban messengers in the Holy Roman Empire also became important. For a fee, they carried private letters and merchant mail. These services were networked with one another and dominated most of the private and commercial correspondence during the 16th century. Their decline came after the Thirty Years' War.

Development outside of Europe

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Arabs managed to build a world empire that stretched from Persia to Spain . The already existing communications links were greatly expanded during this time - this resulted in a well-organized communications system that even used the pigeon post . The couriers were given a special label so that they could be recognized from afar: they were hung a plaque that served as an identity document around their necks using a yellow sash.

The Inca also managed to set up a well-organized messenger system during their heyday between the 13th and 16th centuries. For the messengers, the Chasqui , hostels ( tambos ) were set up at regular intervals of 3 to 5 km along the main roads of the empire . There were always two messengers waiting in front of the house. If they spied another messenger in the distance, they rushed to meet him and took away the messages that were to be delivered. In the case of particularly important or urgent messages, the approaching messengers also made themselves noticeable through a snail's trumpet. Since the Inca culture is considered an advanced culture without writing and it has not yet been clarified whether they also used their knot script for other information than storing numbers, it remains uncertain whether the messengers did not pass most of the messages orally.

A messenger system also existed during the heyday of the Maya culture. But little is known about it.

Development from the early modern period in Europe

Since the 13th century, hostels on tourist routes in Spain, Italy and Germany have offered rental horses. The first state relay for the transmission of messages by changing riders and horses came into being in the Duchy of Milan before 1400. In the second half of the 15th century, King Ludwig XI. from France some post chains with changing horses. The first postal connection organized centrally in terms of time and space was the so-called Dutch postal rate . It was set up in 1490 by Janetto von Taxis with the help of his brother Franz and his nephew Johann Baptista between the court of Maximilian I in Innsbruck and that of his underage son Philipp in the Burgundian Netherlands . When Philip became King of Castile after Isabella's death in November 1504, Franz von Taxis extended the postal lines to Castile . 1516 he was awarded by the Spanish King and later Emperor Charles V the privilege of a main post master of the Netherlands . The postal rates were extended to Rome, Naples, Verona and other cities as required.

It is remarkable that the tight organization of the postal system, which stipulated a rational change of rider and horse at the post office , enabled an average of 166 kilometers of mail to be handled every day. This transport speed of 6.6 km per hour including stops could only be achieved by changing horses numerous times. For comparison: In the military-sporting distance ride between Berlin and Vienna in 1892 , the winners managed 7.8 km per hour without changing horses, but their horses died a few hours after the competition.

At the beginning the post office was closed to private correspondence. Only letters and small items from the dynastic area were allowed to be transported. After 1520, the carriage of private mail on the Dutch postal route became so extensive that it was initially tacitly tolerated and finally approved. In addition to letters and similar items, the Post also carried people who traveled with an escort from post station to post station and changed riding horses.

In 1596 Leonhard I von Taxis was appointed general postmaster in the Holy Roman Empire . The postal system itself has been an imperial shelf since 1597 . In 1624 Lamoral von Taxis was raised to the rank of imperial count and given the fiefdom of the general postmaster. In the Austrian hereditary lands, the post loan was transferred to the house of the couple in 1624 .

The increasing mail traffic led to attempts at administrative improvements and simplifications early on. They mainly applied to the elimination of postal inadequacies in delivery , the reduction of high loss rates of the items, the desire for greater security for the letters and goods entrusted to the post office and the hiring of reliable messengers who should receive adequate wages .

1622 connected Hamburg and Lübeck, 1624 Nuremberg and Leipzig a regular postal service. In the middle of the 17th century , a Brandenburg-Prussian state post was created to compete with the Imperial Imperial Post , which was operated by the Thurn und Taxis . Likewise, the use of stagecoaches began after the end of the Thirty Years War , initially for passenger transport. Along the postal routes , inns were built at the post stations that cooperated with the postal companies. The names that still exist today, such as Gasthaus zur Post, are a reminder of this.

Around 1800 all central European cities were connected to each other by regular mail connections. From the Age of Enlightenment, around the middle of the 18th century, there is evidence of an increase in travel activity.

"Swiss Post creates the material basis for this new dimension of travel."

Development of postage

Receiver pays fee

After a postage dispute there was an agreement for the first time in May 1534 between the postmaster general Johann Baptista von Taxis in the Netherlands, Mapheo von Taxis in Spain and Simon von Taxis in Milan. The postmaster Johann Anton von Taxis from Augsburg acted as referee. After that, the Great Council of Mechelen decided the dispute.

At the beginning of the regular postal service there was no uniform tariff for private customers. The amount of the transport fee was calculated according to the weight of the mail and the length of the route. The payment of the transport fees , i.e. the sum that is now referred to with the word postage , was not paid by the sender , but the recipient paid the fees to the postillon . The postal operator did not ask for payment for the delivery until after he had made it.

Possibly also the thought played a role that the sender, in uncertainty about the fate of the consignment handed over to the post office, would not have wanted to pay in advance. Certainly the point of view that the postal operator, knowing that the transport fee is only paid when the consignment is delivered, is justified in doing everything to ensure that his messengers work as reliably and as well as possible and that they work as reliably and as quickly as possible set goals achieved.

On June 8, 1621 , Malherbes wrote to his friend Claude Fabri , Councilor of Parliament of Provence :

- "Do not hesitate, if you like, to write to me and collect the delivery fee from me, so that the postmen will be more willing to do it quickly."

Paying for the mail by the recipient made it possible, even at a time when postage stamps did not yet exist, to simply drop letters into one of the collection boxes from which the post office administrator collected them , so that the often arduous delivery to the post office could be avoided.

Sender pays fee

In the Holy Roman Empire

An early proof of prepaid postage is the hourly pass from 1506 on the postal route from Mechelen to Innsbruck. After this hour pass one of the assumed Postreiter when passing ride to Speyer a package for Welser . He received several guilders for onward transportation from Söflingen near Ulm to Augsburg.

France

A French receipt for a mail item, for which the fee was paid by the sender against a receipt from the acceptance post office, dates from July 18, 1653, when Jean-Jacques Renouard de Villayer received "royal permission" from Louis XIV , letters from a Paris district to wear after the other.

This royal privilege had not only been made out for Monsieur de Villayer, but it still bore the name of Count de Nogent , who never took part in this postal service - except perhaps for profit. He would thus be an early forerunner of those "relationship exploiters" who achieve advantageous contracts for their clients.

Monsieur de Villayer had his new post office posted in Paris by posting a wall .

- First and foremost, he pointed out that the messengers would work much faster since they did not have to wait for the recipient to pay for the shipment they had handed over.

- The second clue was that it was only right and okay for someone who sends a letter to someone who might not want it to pay for delivery.

- The third argument was: "Through my post many people can write to people they do not want to expect from special politeness to pay the postage, and besides, they can also her lawyer or authorized agent or supplier give notice without them to incur costs. "

"On ... days of the year one thousand six hundred and fifty postage paid ..."

was the text of the receipt that the Villayers company, after inserting the date and amount, issued to the sender as the remaining receipt. This postage receipt, which is not a postage stamp in our sense only because of its format, the handwritten information and the lack of gumming, was attached to the letter to be transported before it was thrown into one of the Villayer post boxes in such a way that “the postman at the Delivery can see them clearly and detach them easily from the letter ”.

Monsieur de Villayer also allowed a blank postage slip to be attached to the postage slip that was filled out for transport purposes so that the recipient could reply if he was willing, without incurring any expense. In doing so, he created the archetype of the reply postage voucher , which is still in use today.

The basic idea of the postage stamp was born.

The postage receipts delivered by the postman to the administration of the Villayer company were probably only used for billing purposes. They were later destroyed in order to rule out any possible misuse through repeated use. Uncompleted postal receipts are unlikely to have been hoarded in large quantities. And Villayer's post was short-lived, because in 1662, after the business was closed, a lady of Spanish origin - Doña Molina y Espinos - was demanding a new royal privilege. Not a single “Billet de porte payé” has survived, any more than any of the other additional receipts that the inventive Monsieur de Villayer had distributed in the Palace of Justice in Paris. They were forms with frequently recurring texts and a blank space for handwritten additions by entering the date and name. The wording was roughly like that of the preprinted "internal letters" of our day:

"Mr. ... if you do not pay us the amount from ... within three days ..."

Only one text of such a passepartout was published in 1838 by the deputy director of the Paris postal administration, MA Piron, in his book Du Service des Postes et de la taxation des lettres. (German. The postal service and the franking of letters by means of a stamp ) published.

Postal history of individual countries

Germany

see main article German Postal History

Austria

- Habsburg Post (1490–1556)

- Habsburg Post (1557–1597)

- Austrian postal history until 1806

- Austrian Post and Telegraph Administration

- Austrian Post AG

- Postal history and postage stamps of Austria

Switzerland

Other European countries

- Danzig

- Denmark

- Finland

- France

- Great Britain

- Ikaria

- Iceland

- Italy

- Liechtenstein

- Norway

- Russia

- Sweden

- Spain

- Hungary

Non-European countries

International organizations

literature

- Wolfgang Behringer : Under the sign of Mercury, imperial post and communication revolution in the early modern period. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35187-9 .

- Martin Gur: The postal system in Galicia from 1772-1820. Dissertation at the University of Vienna , Vienna 2011. With a general historical overview of the postal system in Section II. The postal system, p. 150ff. ( Full text as PDF. )

- Hermann Glaser, Thomas Werner: The Post in its time. A cultural history of human communication, v. Decker Verlag, Heidelberg 1990

- Martin Dallmeier: Sources on the history of the European postal system 1501–1806. 2 volumes, Lassleben, Kallmünz 1977

- Handwortbuch des Postwesens, published by the Federal Ministry for the Post and Telecommunications , 2nd completely revised edition, Frankfurt 1953, p. 298ff.

- Gerd van den Heuvel: Leibniz on the Net. The early modern post as a communication medium of the learned republic around 1700. With ill. Series: Reading room, 32nd Ed. Georg Ruppelt . CW Niemeyer, Hameln 2009, ISBN 3827188326

- Ludwig Kalmus: World History of the Post. Amon Franz Göth, Vienna 1937

- Carl Möller: History of the State Postal Service, 1897 ( full text on lexikus.de. )

- Post log book , Verlag R. v. Decker, Berlin 1875

Individual evidence

- ^ Wolfgang Helck : Keyword postal system. In: Lexicon of Egyptology. Volume IV, 1982, columns 1080-1081

- ^ Lothar Störck: Keyword dove. In: Lexicon of Egyptology. Volume VI, columns 240-241

- ↑ Ed. Müller I., 80

- ↑ Ernst Kießkalt: The origin of the post. Bamberg 1930

- ↑ See Petra Krempien: History of travel and tourism. An overview from the beginning to the present. FBV-Medien-Verl.-GmbH, Limburgerhof 2000, 94-97 and Klaus Beyrer: Des Reiseeschreibens, Kutsche ': Enlightenment awareness in postal travel of the 18th century. In: Wolfgang Griep, Hans-Wolf Jäger (Hrsg.): Travel in the 18th century. Winter, Heidelberg 1986, 50-90.

- ^ Klaus Beyrer: Des Reiseeschreibens, Kutsche ': Enlightenment consciousness in postal travel in the 18th century. In: Wolfgang Griep, Hans-Wolf Jäger (Hrsg.): Travel in the 18th century. Winter, Heidelberg 1986, 50.

- ^ Fritz Ohmann: The beginnings of the postal service and the taxis. Leipzig 1909, pp. 326-329

- ↑ You Service des Postes et de la taxation des lettres

- ↑ Cover: Ordinari-Postzeitung 1679, title vignette; 1. 7-fold royal Great Britain and Chur-Princely Braunschweig-Lüneburg state calendar for the 1743rd year: Directory of postal connections from and to Hanover . Lauenburg 1742; - 2nd notification. Relation oder Zeitung, No. 2, 1609; 3. Chur- and Fürstl. Braunschweig Lüneburgische Post Carte (1770), draftsman Friedrich Wilhelm Ohsen; - 4. Prussian passport f. Leibniz, July 21, 1704; - 5. Leibniz, construction drawing for wagon wheels , detail; - dsb., detailed drawing of a wagon, detail; - dsb., further construction drawing f. Wagon wheels; - dsb., sketch of a wagon wheel with an eccentric hub; - dsb., draft for a "Rollwagen", drawing 1686