Giovanni Battista Agucchi

Giovanni Battista Agucchi (born November 20, 1570 in Bologna , † January 1, 1632 in Susegana ) was an Italian Roman Catholic bishop.

Agucchi was titular archbishop, papal diplomat and writer on aesthetics . He was the nephew and brother of cardinals. He served as secretary of the State Secretariat , then of the Pope himself. After his death, Agucchi was appointed titular bishop and nuncio of Venice. While in Rome he was an important figure in Roman art circles and promoted Bolognese artists. In particular, he was close to Domenichino . As an art theorist, he was rediscovered in the 20th century, having for the first time expressed many of the views better known from the writings of Gian Pietro Bellori a generation later. He was also an amateur astronomer who corresponded with Galileo Galilei .

biography

Agucchi came from a noble family from Bologna, where he was born. He started his career 1580-82 as assistant to his much older brother Girolamo Agucchi (1555-1605) (cardinal from 1604 to 1605), the governor of Faenza in the Papal States was, and then studied in Bologna and Rome. He was appointed canon of the Cathedral of Piacenza , then from 1591 worked for his uncle Cardinal Filippo Sega , an important diplomat of the Pope. He accompanied Sega when this Apostolic Nuncio was in France , then returned with him to Rome in 1594 and remained in his service until Sega's death in 1596.

Then he followed his brother Girolamo into the service of the Papal Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini , whose secretary was Girolamo. Aldobrandini was the nephew of Pope Clement VIII (1592-1605). Agucchi accompanied Aldobrandini on his embassies to Florence and France to negotiate the Treaty of Lyon (1601) and the marriage of Henry IV of France, then in 1604 to Ravenna, where Aldobrandini had been appointed archbishop. A trip to Ferrara followed in the same year. The death of Pope Leo XI. and his replacement by Pope Paul V in 1605 meant the loss of papal favor for both men. During this time, Agucchi was able to devote himself to his personal interests until 1615, when Aldobrandini returned to his favor and office. He was also a protégé of the art-loving Cardinal Odoardo Farnese , as whose secretary he acted.

Aldobrandini died in 1621 and Agucchi became secretary ( Segretario dei Brevi ) to the new Pope Gregory XV in the same year . , who also came from Bologna. Pope Gregory died in 1623, and in the same year his successor Urban VIII made Agucchi titular bishop of Amasya in partibus infidelis and appointed him apostolic nuncio of the Republic of Venice . Venetian politics at the time were highly polarized between pro- and anti-papal factions, and Agucchi's period largely coincided with the unstable rule of Doge Giovanni I Cornaro (1625-29), whose election Agucchi had sought but whose rule was something like was a disaster. Agucchi left Venice in 1630 to avoid the plague and died the following year after a stay in Oderzo in the Castello San Salvatore in Susegana .

In the art world

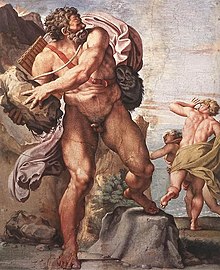

Agucchi was a cultivated intellectual and friend of many artists who played an important role in introducing painters from his hometown of Bologna to the patrons of the Roman Curia . He was “an avid correspondent on his own and for others” and many unpublished letters have survived, as have those cited by Carlo Cesare Malvasia in his works. He often appears in discussions about Roman orders of the time, e.g. B. he proposed Ludovico Carracci for an altarpiece in St. Peter's Basilica , but without success. Annibale Carracci had received his own recommendation to Cardinal Odoardo Farnese from the cardinal's brother, Ranuccio I Farnese , Duke of Parma, but became a friend of Agucchi in Rome and is mentioned in his writings, which also contain important biographical information about the Carracci, cited as a model. Agucchi may have advised Carracci on the complex and learned mythological iconography of his frescoes The Love of the Gods for the Palazzo Farnese , Carracci's first commission in Rome. They are still a milestone for the Roman Baroque. He gave Annibale his last holy communion before his untimely death in 1609 and wrote his epitaph for the Pantheon .

Domenichino joined Carracci in his work on the Palazzo Farnese. Agucchi and his brother made him with Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini and the future Gregory XV. known. Domenichino lived in Agucchi's household from 1603/4 to 1608, and according to Bellori , one of the characters in Domenichino's fresco is Meeting of Saint Nilus with Emperor Otto III . (c. 1609–10; Grottaferrata Abbey , Cappella dei SS Fondatori) a portrait by Agucchi.

Cardinals Odoardo Farnese and Pietro Aldobrandini were political opponents, albeit less after a marriage between the two families in 1600. However, they were the two leading proponents of Bologna painting in Rome, who managed to give the Bolognese "an almost monopoly" for placing large orders for palaces in the 1610s. Cardinal Aldobrandini's personal preference was the late Mannerist style of Giuseppe Cesari (the Cavaliere d'Arpino) and others. His support for the Bolognese must largely be attributed to Agucchi's advocacy. The cardinal commissioned Domenichino 1616-18 with eight frescoes with the story of Apollo for the Villa Aldobrandini outside Rome. They are now in the National Gallery, London . Agucchi's older brother, Cardinal Girolamo, commissioned Domenichino to paint three frescoes depicting the life of Saint Jerome in the portico of Sant'Onofrio in Rome, which are still in place today. This happened in 1604, completed in 1605, at the time Domenichino was living with Agucchi. In the church there is also Domenichino's portrait of Agucchi's uncle, Cardinal Sega, on his monument.

From Annibale Carracci, Cardinal Aldobrandini commissioned a series of decorative frescoes with religious themes in landscapes for his palace in Rome, which today houses the Doria Pamphilj Gallery and is still owned by the family, as well as the Domine, quo vadis? in the National Gallery London, and a Coronation of the Virgin Mary acquired from the Mahon Collection by the Metropolitan Museum of Art . By 1603 he owned six works by Carracci, including two of the above. The Bolognese artist Guercino only spent the years during the papacy of Gregory XV. in Rome, where his style shifted towards classicism. Denis Mahon felt that this change was largely a response to Agucchi's urging, and like most commentators, Mahon felt that the change was, by and large, not an improvement. Eva-Bettina Krems suspects that Agucchi is responsible for the connection between the Lombard sculptor Ippolito Buzzi and Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi , who provided him with a steady stream of works over several years.

Portrait in York

The beautiful and intimate portrait at York Art Gallery had always been attributed to Domenichino until a 1994 article suggested that it was done by Annibale Carracci from around 1603 instead. It was owned by Agucchi until his death. When the York Gallery was closed for reconstruction in 2014-15, it was loaned to the National Gallery in London and exhibited there. Domenichino and Agucchi worked together on the monument to Girolamo Agucchi in the Church of San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna, for which drawings are in the British Royal Collection (Royal Library, MS. 1742).

Fonts

Agucchi's most important published work is a very incomplete but important Trattato della pittura (“Treatise on Painting”), probably written in 1615, the manuscript of which is in the library of the University of Bologna (MS. 245), which is also an unpublished one Latin biography of his brother Vita Hieronymi Agucchi (MS 75). The trattato was published posthumously in Rome in 1646 under the pen name Gratiadio Machati, which Agucchi had used during his lifetime (a convention for a clerical writing on secular affairs). It was included in the preface by GA Mosini, the pseudonym of Giovanni Antonio Massani, to a collection of prints after Annibale Carracci entitled Diverse figure al numero di ottanta ("Eighty different figures"). There is an English translation by Denis Mahon (1947) who did much to spark interest in Agucchi as a previously overlooked theorist

The trattato "is a living document about official Roman art circles in the years 1607-15 and focuses specifically on the glorification of the idea della bellezza , which Agucchi particularly identifies with ancient sculpture". The work shows evidence that it was influenced by conversations with Domenichino, which reflect a split in national and regional painting schools that the latter described in a letter as his own. It is essentially the one used up until the 20th century that distinguishes the Roman, Venetian, Lombard and Tuscan (Florentine and Sienese) schools in Italy. It is believed that the trattato may in fact have been a collaboration, with Agucchi's elaborate prose taking up Domenichino's thoughts, although most of the time it is believed that it is not.

Agucchi drew from Neoplatonist thinking, in which "nature is the imperfect reflection of the divine and the artist must improve it in order to achieve beauty", a view that was already common practice in the previous century. He held up classical sculpture, Raphael and Michelangelo as models who had observed from "nature" but selected and idealized what they represented, and denigrated the Mannerists . Above all, Annibale Caracci had saved art from its artificiality and returned to the representation of improved nature. The realism of Caravaggio and his followers was also lamented.

Apart from the series of lectures for the Accademia di San Luca by Federico Zuccari , its first president, there was a general lack of art theoretical writings during this period. These were published as L'idea de 'Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti (1607) and referred to as "the swan song of the subjective mysticism of Mannerist theory". The lectures themselves were abandoned when the first were received with hostility by the Bolognese and Caravaggists alike. The idea may have provoked Agucchi to start his own work. Despite its delayed and opaque publication, Agucchi's ideas represent the earliest exposition of the "classical idealistic theory" that would prevail in most of the Roman art world in the 17th century.

The younger antiquarian, Francesco Angeloni , was a close friend who had also worked for the Aldobrandini, in his case Pope Clement VIII, and who owned at least one copy of the York portrait. Angeloni raised his nephew Gian Pietro Bellori (1613–1696) and introduced him to Agucchi and the Bolognese artists in Rome. Bellori was to take up many of Agucchi's ideas in his own very influential writings on art.

Silvia Ginzburg has pointed out that an earlier work by Agucchi, Descrizione della Venere dormiente di Annibale Carrazzi (“Description of the Sleeping Venus by Annibale Carracci”), which was written around 1603 but was not published until 1678, shows a completely different approach to painting by recognizing the speed of Carracci's style and his ability to paint without drawing, both qualities that the trattato does not approve of. She suspects that the reaction to the style of Caravaggio explains the change, which can also be referred to in a letter from Agucchi from 1603.

Agucchi was also interested in astronomy and mathematics and was a member of the Accademia dei Gelati of Bologna. He led a long correspondence with Galileo Galilei in 1611-13 , including passing on data from his own astronomical observations, and in 1611 lectured on Jupiter's moons . Galileo made the first recorded observations of it in 1609.

literature

- Gabriele Finaldi , Michael Kitson: Discovering the Italian Baroque: the Denis Mahon Collection ' . National Gallery Publications, London / Yale 1997.

- JM Fletcher: Francesco Angeloni and Annibale Carracci's 'Silenus Gathering Grapes' . In: The Burlington Magazine . tape 116 , no. 860 , November 1974, p. 664-666 , JSTOR : 877872 .

- Sylvia Ginzburg: The Portrait of Agucchi at York Reconsidered . In: The Burlington Magazine . tape 136 , no. 1090 , January 1994, p. 4-14 , JSTOR : 885693 .

- Eva-Bettina Krems, Eva-Bettina: The 'magnifica modestia' of Ludovisi on Monte Pincio in Rome. From Hermathena to Bernini's marble bust of Gregory XV . In: Marburg Yearbook for Art History . tape 29 , 2002, pp. 105-163 .

- Rudolf Wittkower : Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750 . 3. Edition. Penguin / Yale History of Art, 1973.

- Peter Boutourline Young: Agucchi, Giovanni Battista . In: Grove Art Online . Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press ( oxfordartonline.com ).

- Roberto Zapperi: AGUCCHI, Giovanni Battista. In: Alberto M. Ghisalberti (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 1: Aaron – Albertucci. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1960.

- Agucchi, Giovanni Battista . In: Lilian H. Zirpolo (Ed.): Historical Dictionary of Baroque Art and Architecture . ( google.com ).

- Denis Mahon : Studies in Seicento Art and Theory . London 1947.

- Norman Land: The Anecdotes of GB Agucchi and the Limitations of Language . No. 22.1 . Word & Image, 2006, p. 77-82 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Zapperi

- ↑ a b c d e f Young

- ↑ Ginzburg, 5; Young; Zapperi

- ↑ Ginzburg, 6, 8, N. 30

- ↑ Young; Zapperi; Wittkower, 38-39

- ↑ Wittkower, 57, 63 (63–68 on the scheme)

- ^ Ginzburg, 8 N. 29

- ↑ Young; Finaldi and Kitson, 60

- ↑ Young; Photo of the fresco - the monk on the right side of the cross appears to be most similar to the portrait of Domenichino in York, made about five years later

- ^ Finaldi and Kitson, 38

- ↑ Wittkower, 38–39, 80 Apollon frescoes; 39 cited

- ^ Finaldi and Kitson, 60

- ↑ Finaldi and Kitson, 15-16, 21 N.37, summary of Seicento studies

- ↑ Krems

- ↑ Ginsburg, continuous, p. 10 on the transition to his niece as heir

- ↑ portrait of Monsignor Agucchi, 1603-4, Annibale Carracci . Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- ^ Translation and edited by Denis Mahon in his Studies in Seicento Art and Theory (London, 1947); on Mahon, see Finaldi and Kitson, 15-16, and [1] . Here is a long excerpt with an introduction pages. 24-30

- ↑ Zirpolo, 47-48; Finaldi and Kitson, 15-16

- ↑ Zirpolo, 47

- ↑ Zirpolo, 47-48; Young

- ^ Wittkower, 39 (quoted, "swan song" quotation from R. Lee), 266

- ↑ Fletcher, 666 and Note 19; also Ginzburg, 10–11, aggravating aspects

- ↑ Young; Zirpolo, 48

- ↑ Ginzburg, 8-10

- ↑ Young; Zirpolo, 47

- ↑ Galilei, Galileo: Sidereus Nuncius . Ed .: Translated and prefaced by Albert Van Helden. University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London 1989, ISBN 978-0-226-27903-9 , pp. 14-16 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Agucchi, Giovanni Battista |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Agocchi, Giovanni Battista; Agucchia, Giovanni Battista; Dalle Agocchie, Giovanni Battista |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian bishop, diplomat and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 20, 1570 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bologna |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 1, 1632 |

| Place of death | Susegana |