letter

The letter (from the 12th century originally as a sentbrief in today's meaning, from Latin brevis libellus or in the 6th century from late Latin breve , "short letter, certificate", to brevis "short") is a message recorded on paper which is usually delivered by a messenger and contains a personal message intended for the recipient. A letter is folded ( folded letter ), is also a (pharmaceutical) name for a bag or pharmacist letter, or is sent in an envelope (envelope letter ). It can also refer to a letter.

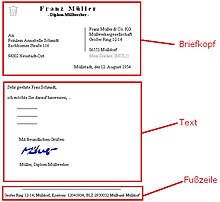

The letter usually consists of the place and date of writing, the salutation , the text and the closing formula . The envelope usually contains information about the sender, the recipient's address and, in the case of dispatch, a franking .

The letter is a cultural product that has to overcome illiteracy and that takes the development of the written language as its basis. Its use as a communicative medium requires writing and reading skills (for example as writing in a visual-graphic perception in the sense of writing , reading or the use of writing materials and writing media).

history

The beginnings of writing such a message go back to the Babylonians , who carved messages on clay tablets . In ancient Egypt, on the other hand, papyri were used as carriers for letters. In ancient Greece and Rome , wooden panels coated with wax were used for this purpose . The purpose of a letter has hardly changed since the first authors of such communications: it is still a means of public expression (e.g. letters to the editor in a newspaper ), a literary form (cf. Goethe's epistolary novel " The Sorrows of Young Werther ") , the Pauline letters of the New Testament of the Bible ) as well as an instrument for the distribution of official (e.g. culture ministerial letters) and transmission of personal messages (e.g. love letters ). In the early modern period, the letter also developed into a collector's item; one of the largest collections in Germany that has survived since then is that of Christoph Jacob Trew .

In the humanities, letters are examined according to historical, literary and cultural studies aspects. A pioneer of German letter research was the librarian and cultural scientist Georg Steinhausen , whose history of the German letter appeared in two volumes from 1889–1891.

History of the letter and the post in 18th century France

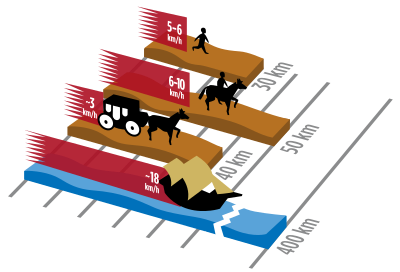

The mail transport system in the 18th century could generally fall back on different modes of transport. These served a postal data exchange with different transport speeds.

Correspondence requires, on the one hand, the appropriate writing material and writing material and, on the other hand, the transport of the written texts etc. from one place to the next. The postage letters (i.e. the recipient paid the transportation fee) was the rule. Postage means unpaid fee. As early as the 16th century, mailings in France were marked en diligence (translated "with haste", also "with care"). It is from this note that French stagecoaches were given their designation diligences . At the end of the 18th century, the steel nib was developed, which was embedded in a holder, the penholder. Previously, the quills were common and gradually replaced.

Until the development of chlorine bleach ( Eau de Javel 1789 by Claude-Louis Berthollet ) the only available fiber raw materials for paper production were the light rags made of linen , hemp or, very rarely, cotton . In connection with spinning and rope mill waste, so-called rag paper was produced with it.

In the 18th century, the main means of travel and transport available were walking, independent riding, traveling in a carriage ( stagecoach ) or across waterways. In 1671, the Pajot and Rouille families founded the first post office, premier center Postal de Paris, in the center of Paris ( Paris City Post Office ) at rue des Bourdonnais № 34 across from № 9 and 11 Rue des Déchargeurs . They were Ferme générale des Postes under Louis XIV.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the letter post appeared, which was financed by contributions from the surintendant général des postes . A price was charged for the letter, which was paid for by the recipient. The letters traveled from one post office to the next, interrupted by the relay stations where the horses were changed. The mail transports were accompanied by a postillon. He was responsible for the guidance to the next station and then brought the horses back to the original relay station alone. The average distance between the relay stations was 7 miles or 28 km, hence the famous seven mile boots in the fairy tale of Charles Perrault Le Petit Poucet .

Mail and travel routes through France

In the 18th century, the average distance between two relay stations was 16 kilometers. A letter sent from Paris took 2 days and 8 hours to Lyon and a little more than 4 days to Marseille. At that time there were around 1,400 post offices. In 1760, Claude Humbert Piarron de Chamousset (1717–1773) founded a post office in Paris. With 200 mail carriers, facteurs - they drew attention to themselves with rattles - he took care of the mail delivery and ensured distribution within three days.

The "newspaper" letter

In the 16th century, a letter form that approximated the newspaper (and shows parallels to the social network on the Internet ) became common in Europe : “In order to get his messages to larger circles, the letter writer soon no longer addressed his letter to just one person The newspaper writer Ludwig Salomon noted in 1906 that these letters consisted of two parts: the “intimate” part, which was in its own envelope within the larger envelope, and a loose one Semi-public part placed in the envelope, which the addressee should pass on to acquaintances and like-minded people if he thought it was interesting. Through this targeted distribution of news in a manageable circle, decentralized discussion circles and growing social networks emerged among the correspondents of the time. The semi-public parts of the letter were called Avise, Beylage, Pagelle, Zeddel, Nova and finally just newspaper . "The form in which the writers of these 'newspapers' reported their news was almost always purely relational" - that is, one of the context, nothing hard researched, more of a compilation of news and opinions.

The letter as a historical source

From the historical point of view , only a private letter is a “letter”. If the author or the recipient is an official or an institution, then the document belongs to the documents or files. An " open letter " that is actually addressed to the general public is one of the literary works. Because of the many mixed forms (e.g. business letters that also contain private matters), this terminology is not always mandatory, even among historians.

Letters used to be very expensive and were more likely to be sent by officials or wealthy merchants; From the 18th century onward, correspondence expanded to include other upper class circles. This century is also called the century of letters. Only occasionally, on important matters, did ordinary people write letters. There was also the profession of letter writer. Often phrases were used, which meant that a lot of individuality was lost.

History has also used traditional correspondence since the 19th century. In the 20th century, the interest in everyday history and the history of the "little people" increased, so that the post of these people came more into the spotlight. Examples of this are soldiers' letters from the world wars to their homeland, which are of interest not (only) because of individual fates, but because statements about the life and mentality of larger groups of people are based on them.

The letterhead

As letterhead is called the pre-printed on the first page of a letter usually above elements. While she was always limited on private stationery on few data and little decorative motifs show (possibly for example, in embossing inserted Arms), the elaborate letterheads of companies certainly of historical interest. The simple beginnings go back to the beginning of the 19th century. With the increase in the movement of goods and the depersonalization of commercial activities, a representative external form of correspondence became more and more important. Technically, this need was met by the high-speed press patented in 1813 and an upswing in lithography from 1820 onwards. Popular motifs in the second half of the 19th century were, in addition to ornamental and allegorical jewelery, above all factory views and decoratively arranged reproductions of award medals.

Postal matters

Until the 19th century, folded sheets of paper were the common shape of a letter, while a special envelope was the exception. The shape of a folded sheet of foliage became the normal size of the letter, about 9 × 17 cm, the average weight was about 1 lot or ½ an ounce = about 15 g. All letters had to be sealed (repealed in 1849). The Post was not liable for the loss of a letter. The seal served to protect the confidentiality of the letters. The fee was negotiated individually from post office to post office; there were rarely fixed tariffs.

In the Kingdom of Westphalia , all shipments were to be calculated in francs and cents. From November 1, 1810, payments were made based on distance and weight. The simple letter was allowed to weigh 8 g, items over 60 g should be transported with the driving mail.

In the Duchy of Braunschweig in 1814 the simple letter weight was 1 lot, the price rose with each lot and the distance. In 1834 simple letters were only allowed to weigh ¾ lot, the price rose from 1 lot per ½ lot by the postage fee. Letters over 4 lots should be carried with the Fahrpost. From 1855, the simple letter was not allowed to weigh a whole lot, the distance no longer played a role. Since 1863 1 lot had to be paid for 1 groschen. In 1865 there were only two weight levels, up to 1 postlot = 1 groschen, up to 15 = 2 groschen.

In Prussia, the postal tax regulation of 1825 regulated postage based on distance and weight. The simple letter was allowed to weigh ¾ plumb. Letters over 2 lots belonged to the driving mail. In 1860, the mail weight in domestic and club traffic was limited to 15 g (250 g). From 1861 the postage was up to 1 lot and double postage up to 15 lots.

From 1830 onwards, commercially produced envelopes came onto the market; from 1840 onwards they were produced by machines. In 1849 letters no longer needed to be sealed. Postage stamps were then introduced in 1850, and envelopes with printed stamps were added in 1851.

In the northern German postal district, up to 1 lot = 1 Sgr. up to 15 lot = 2 Sgr. With the Reichspost 1875 up to 15 g = 10 Pfg. And over 15 g = 20 Pfg. The simple letter weight increased in 1900 to 20 g. At the same time, cardboard boxes and rolls were allowed.

Newly introduced:

- 1897 official card letters as an official form.

- 1908 window envelopes.

- 1922 Official file letters up to 500 g.

- In 1923 the maximum weight for letters increased from 250 g to 500 g.

After the Second World War, the maximum weight was increased from 500 g to 1 kg in 1947. From 1948 to 1956, almost all items in the western zones or the Federal Republic had to be franked with the Notopfer Berlin tax stamp in addition to postage. On March 1, 1963, standard letters were offered at a special rate. In 1993 4 basic products (standard, compact, large and maxi letters) were introduced. In 1995 the Bundespost was privatized.

Nowadays letters are mostly sent via postal services such as B. transmitted by Deutsche Post , its content is protected by an envelope and the letter secret . They should, but do not have to be, locked. Letters are mostly from the sender in advance paid ( cleared ). This is done by attaching postage indicia in the form of postage stamps , franking marks or imprints by the postal service provider. In addition, a postal address of the recipient must be written on the envelope, possibly also the address of the sender . This enables letters to be returned smoothly in the event that the recipient refuses to accept delivery or cannot be identified. Special forms of delivery are the German delivery certificate , the Austrian return receipt and the internationally usable registered mail .

With the increased use of electronic mail and E-Postbrief, the importance of traditional letters has been declining for years. While Deutsche Post carried 16 billion letters in 2008, it was only 12.7 billion in 2017, 92% of which were business letters.

Norms

The letterhead as well as the design of business letters is in Germany by the German Institute for Standardization with the standard DIN 5008 regulated.

In cases in which the recipient's address has changed and a forwarding order has been issued, letters with an outdated delivery address can also be redirected or forwarded to the recipient.

If the shipment is lost, no liability is assumed in the case of a normal letter, see also Post's obligation to pay compensation .

Electronic mail

Since the 1990s , traditional mail has been increasingly supplemented by e-mail , which has some significant advantages (speed, price), especially in business mail. For the transmission of important texts (e.g. love letters , contracts , diplomatic notes ) the letter form is still common. Since the advent of e-mail, conventional mail has also been jokingly called “ snail mail ” or “ bag mail ”.

A special form of the letter is the advertising letter or the advertising mailing , also called mailing .

E-mail letter

The e-mail letter of Deutsche Post is a hybrid mail service with a connected website for the exchange of electronic messages over the Internet. It is in competition with the legally regulated De-Mail procedure.

Non-private letters and documents

Open letters are those that are published - for example in the mass media - and have a double addressee: the explicitly named recipient and the public. Other special forms are the letter to the editor and the profile . Letters are also used to describe instructive or commanding messages to groups of people, for example letters to Christian communities in the New Testament of the Bible , e. B. Paul’s letters and the letter to the Hebrews , Luther’s “ Letter from Interpreting” or the pastoral letter in the Roman Catholic Church .

Letters in the broader sense are master craftsmen's letters that can be viewed as certificates , as well as letters of honor (as official recognition for a voluntary activity or as an award ). Also make mortgage bonds represent a certificate in certificated form issued by appropriately trusted institutions. The expression "letter and seal " indicates the meaning of letter as a certificate .

See also

- Greeting (correspondence)

- Letter poem

- Epistle novel

- Ban letter

- waybill

- Charter

- Mortgage note

- Family letters from Fu Lei

literature

Collections of letters

- Walter Benjamin (ed.): German people . Lucerne 1936; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992. ISBN 3-518-37470-2

- Rüdiger Görner (Ed.): More soon. The book of letters. German-language letters from four centuries. University Press, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-940432-25-4 .

- Jens Haustein (Ed.): Letters to the father. Testimonies from three centuries . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1987. ISBN 3-458-32745-2 .

- Walter Heynen (Ed.): The book of German letters . Insel, Wiesbaden 1957.

- Katharina Maier (Ed.): Great Letters of Friendship - “Our souls are on your toes; A thousand very, very best you! ” Marix, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-86539-256-5 .

- Jürgen Moeller (Ed.): "I hope heaven will keep Germany". The 19th century in letters . Beck, Munich 1990. ISBN 3-406-34754-1

- Jürgen Moeller (ed.): Historical moments. The 20th Century in Letters . Beck, Munich 1999. ISBN 3-406-42119-9

- Claudia Schmölders (Ed.): Letters from famous women. From Lieselotte from the Palatinate to Rosa Luxemburg . 2nd edition, Insel, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1994. ISBN 3-458-33205-7

- Georg Steinhausen (Hrsg.): German private letters of the Middle Ages . 2 vols. Weidmann, Berlin 1899, 1907.

- Hermann Uhde-Bernays : Artist letters about art. From Adolph von Menzel to the modern age . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

Secondary literature

- Bibliography on letter research from the Institute for Text Criticism

- Rainer Baasner (Ed.): Letter culture in the 19th century . Niemeyer, Tübingen 1999. ISBN 3-484-10791-X

- Klaus Beyrer and Hans-Christian Täubrich (eds.): The letter. A cultural history of written communication . For the exhibition in the Museums for Post and Communication in Frankfurt am Main (1996–1997) and Nuremberg (1997). Edition Braus, Heidelberg 1996. ISBN 3-89466-169-0

- Anne Bohnenkamp and Waltraud Wiethölter: The Letter - Event & Object . Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2008, with numerous illustrations. Catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the Free Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurt Goethe Museum from September 11 to November 16, 2008 (Organizer: the same in connection with the German Literature Archive Marbach). ISBN 978-3-86600-031-5

- Rolf-Bernhard Essig, Gudrun Schury: picture letters. Illustrated greetings from three centuries . Knesebeck, Munich 2003. ISBN 3-89660-158-X

- Gerald Lamprecht: Field Post and War Experience. Letters as a historical-biographical source . Contemporary history studies in Graz. Vol. 1. Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck et al. 2001. ISBN 3-7065-1549-0

- Reinhard MG Nickisch : Letter . Metzler, Stuttgart 1991. ISBN 978-3-476-10260-7

- Henner Reitmeier: From the post to the post , in: Die Brücke , No. 161, 3/2012, pp. 5-7

- Anita Runge, Lieselotte Steinbrügge (ed.): The woman in dialogue. Studies on the theory and history of the letter . Results of women's research. Vol. 21. Metzler, Stuttgart 1991. ISBN 3-476-00759-6

- Fritz Schlawe: The letter collections of the 19th century. Bibliography of letter editions and complete register of letter writers and letter recipients 1815–1915 . 2 half volumes. Metzler, Stuttgart 1969.

- Ulrich Schmitz, Eva Lia Wyss: Letter communication in the 20th century . Osnabrück contributions to language theory. Vol. 64. Obst, Duisburg 2002. ISBN 3-924110-64-6

- Georg Steinhausen: History of the German letter. On the cultural history of the German people . 2 vol. Gaertner, Berlin 1889-1891, Weidmann, Dublin / Zurich 1968 (repr.).

- Christine Wand-Wittkowski: Letters in the Middle Ages. The German-language letter as secular and religious literature . Publishing house for science and art, Herne 2002. ISBN 3-924670-36-6

- Julia Stadter: The letter in the mirror of the arts. Letter motifs and stage letters in painting, literature and music theater . Studiopunkt-Verlag, Sinzig 2015. ISBN 978-3-89564-164-0

- Arnd Beise, Jochen Strobel (in collaboration with Ute Pott) (Ed.): Last letters. New perspectives on the end of communication . Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2015, ISBN 978-3-86110-576-3

Web links

Prices for postage letters / postcards in Germany on the Deutsche Post website

Individual references, comments

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Jürgen Martin: The 'Ulmer Wundarznei'. Introduction - Text - Glossary on a monument to German specialist prose from the 15th century. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1991 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 52), ISBN 3-88479-801-4 (also medical dissertation Würzburg 1990), p. 121 ( brievelin ).

- ↑ a b letter. In: Wolfram Grallert: Lexicon of Philately. 2nd edition, p. 66, Phil * Creativ GmbH, Schwalmtal 2007

- ^ Karl-Ernst Sommerfeldt , Günter Starke, Dieter Nerius (eds.): Introduction to the grammar and orthography of contemporary German. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig 1981, p. 23 f.

- ^ [2] Voltaire : Travels in the 18th century. In: correspondance-voltaire.de. Voltaire Foundation, accessed on July 27, 2012 (PDF; 716 kB, German).

- ↑ Histoire de la poste des origines à nos jours. (PDF; 162.72 kB)

- ^ Salomon refers here to R. Graßhoff: Die Briefliche Zeitung des XVI. Century, Leipzig 1877, p. 51 ff

- ^ Ludwig Solomon: History of the German newspaper system. First volume. P. 3 f., Oldenburg, Leipzig 1906

-

↑ Lit .: Angelika Marsch: Article letter heads , in: Christa Pieske: ABC des Luxuspapiers, production, distribution and use 1860-1930. Museum for German Folklore, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-88609-123-6 , p. 100.

Collection: Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv Foundation , Dortmund (500,000 copies) - ↑ The burden and pleasure of traveling. Or about the inconvenience of getting around by land 1750–1815 Part 1: The travelers and their equipage (2010) (PDF; 3.4 MB); Part 2: About travel itself, locomotion and obstacles (2010) (PDF; 2.6 MB)

- ↑ Competition on the German postal market. Reply of the Federal Government, Bundestag printed paper 19/4122. In: dip21.bundestag.de. German Bundestag , August 31, 2018, accessed on September 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Also available online , accessed on October 12, 2012