Eva Faschaunerin

Eva Kary , née Eva Faschauner (born December 21, 1737 in Malta , Carinthia ; † November 9, 1773 in Gmünd , Carinthia), known as Eva Faschaunerin , was an Austrian farmer and convicted murderer.

The mountain farmer's daughter was accused of having poisoned her recently married husband Jakob Kary with arsenic in the food, which led to the death of the latter. In a three-year inquisition process, they incriminated evidence . After the horror , she confessed to the murder , and later provided further information about her approach under torture . She was sentenced to death by beheading and executed at the Galgenbichl execution site in Gmünd . It was the last execution in Gmünd. Her story then repeatedly inspired people to deal with it artistically or literarily. The result was a novel, plays, (musical) performances and a film on the subject.

Life

Eva Faschauner was born in 1737 as the youngest daughter of the mountain farmer couple Christian Faschauner and Maria Huber at the highest farm on Maltaberg, called Faschauner- or Schauner-Hube. Eva Faschauner had an older sister Maria. She later married Johann Mitterberger from Krainberg to the southeast. Two brothers died at an early age. Maria Huber died in 1749 and Christian Faschauner married Katharina Gigler for the second time between 1749 and 1752. From this second marriage came two half-sisters of Eva Faschauner. On February 7, 1770, she married Jakob Kary, who was born on July 6, 1741, known as Hörlbauer, from Untermalta. He died on March 11, 1770 under strange circumstances. Eva Kary was arrested on April 2, 1770 and sentenced to death by beheading on February 16, 1773 for poisoning. She made a petition for clemency, but it was rejected. Eva Kary died on November 9th, 1773 at Galgenbichl near Gmünd.

Criminal case

There was no male successor at the Faschauner farm, so Christian Faschauner promised his daughter that she could take over the farm with a husband. Eva Faschauner had already turned down several courtiers and wanted to remain single. At the beginning of 1770, two of Jakob Kary's suitors came to the Faschauner farm again. This time the advertisement was not rejected and the very next day Eva Faschauner and her father arrived at Jakob Kary's to take a look at the farm. The court was considered heavily in debt. Therefore the farmer was dependent on a wealthy bride. When Eva Faschauner got to know Jakob Kary's condition, she is said to have been shocked. Even so, she insisted on the marriage and asked her father to pay the debts of her future husband and the cost of the wedding.

Christian Faschauner agreed to the marriage. During the wedding preparations, however, Jakob Kary seriously offended his peasant pride. He himself appeared at the Faschauner farm in his wagon to bring the chest with his bride's belongings, the so-called bridal box, to his court. According to tradition, Jakob Kary should have asked his neighbors to do so. Christian Faschauner was no longer available for the bride and groom and was difficult to reconcile. The wedding ceremony took place in the parish church of Malta by the local pastor Andreas Prugger. The descriptions of Eva Kary's state of mind after the wedding are different. On the one hand, she is said to have been very serious and to have visited her father several times. On the other hand, she is said to have sometimes cried dejectedly in a corner of the room, or sat there in thought and made no progress with work. On March 9, 1770, a Friday, the traditional Lent was filled noodles for lunch . The leftovers from lunch were prepared by Eva Kary as an afternoon snack for her husband. He didn't finish everything and Eva Kary offered the rest to her husband's stepmother. She didn't eat any of it herself. Later, her husband and stepmother suffered from malaise and vomiting. Jakob Kary's condition in particular deteriorated. He passed away the following Sunday while the stepmother was recovering. The pastor noted in the death register:

“Obiit Sacramentaliter confessus non tamen Ss. Viatico propter continuum vomitum, nec S. Unctiore munitus propter non agnitum mortius periculum Jacobus Kayre rusticus at the Hörlhube in Unterdorf aetatis suce 35 annorum. "

"Jakob Kayre Bauer at the Hörlhube in Unterdorf at the young age of 35 died with the sacrament of confession, but without holy communion because of uninterrupted vomiting and [there was] no last holy rites because of failure to recognize the danger of death."

Jakob Kary was buried in the local cemetery. As a result of observations on the sick person and the corpse, rumors arose that he did not die of natural causes. The dead man's lips and face had turned a bluish tint, which was interpreted as poisoning. People said of the widow that she was not touched by her husband's death. The Count Lodronsche Herrschaft in Gmünd summoned Eva Kary and asked her about the circumstances of her husband's death. It was explained to her that public opinion assumed death by poisoning and it was also mentioned that the possession of " Hittrach " (arsenic) was strictly forbidden and would be severely punished. Eva Kary defended herself by stating that there was no arsenic in her house and that she was not familiar with it. The district court clerk of Gmünd, a kind of police officer at the time, finally made a written complaint to the district court on March 31, 1770 . As a result, the court clerk and two servants were sent to the Hörl farmer in Malta on April 1, 1770 to keep an eye on the residents. A court commission followed on April 2, 1770 , consisting of the lordly caretaker and district judge Franz Anton Straßer, the sworn surgeon Anton Karl von Willburg , the Bader Anton Hinteregger, the saddler Leopold Rudiferia as assessor and the scribe Johann Wilhelm. Simon Koch, known as Thomanriepl, as the village judge of Malta and the parish priest Bernhard Langsam supplemented the commission as locals.

The commission stayed at the Kramerwirt in Malta to interrogate the residents. So that they could not agree to meet each other, they were monitored by the court clerk. At the same time , with the permission of the local pastor, the body of Jakob Kary was exhumed and autopsied in the tower room of the Kronegghof by the doctor from Willburg. He found that the internal organs were healthy except for inflammations in the gastrointestinal tract and a liquid discharge there. The discharge poured on embers gave a garlic odor. Everything pointed to poisoning, either from a corrosive liquid or from arsenic. The residents of the house testified that arsenic was present at the Hörlbauern. In the so-called tile room there was a small box, called "Almerkastl", with two compartments. In the upper one was a lump of arsenic in a linen pouch, a little of which was used for cattle diseases or for calving . There was no time left to question Eva Kary that day, so she should be taken to Gmünd for interrogation. She is said to have reacted with dismay. When she saw her father leaving the inn, she is said to have thrown herself screaming at his feet and asked him not to leave her for heaven's sake. For the duration of the trial, your father was given responsibility for managing the Hörl-Hof. Eva Kary defended herself extremely skillfully and confessed nothing. She spent the years 1770 and 1771 in custody in the dungeon of the Gmünd Regional Court, popularly known as "Keichn" or "Kotter".

Eva Kary was charged with the following evidence:

- The farmer asked his wife twice to eat the snack. However, she declined with the explanation that she was not good.

- The farmer didn't finish the snack completely, whereupon Eva Kary offered the rest to the stepmother. She didn't want to eat it at first, but was asked again by the farmer's wife.

- When they gave testimony, the stepmother and the maid assured that they were not present while the snack was being prepared. Nevertheless, Eva Kary stated that both of them would have been present during the preparation and would have seen if she had added something to the snack. Even during the confrontation, she tried to convince the two of them to change what she said.

- Eva Kary stated during interrogation that the poison was in the lower compartment of the box, while everyone else stated that it was in the upper compartment.

- Eva Kary is said not to have made any particular effort or showed any pity during the farmer's illness. Her indifferent behavior on the weekend when the farmer died was particularly noticeable. She went to evening prayer on Saturday and Sunday morning to Sunday mass and didn't come back until around noon.

- It was evident that a piece of the poison had been cut off.

A confession from Eva Kary was required to be convicted. Therefore, the case was withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the regional court of Gmünd by the regional governor of Carinthia on June 20, 1772 and transferred to the ban judge Benedict Alphons von Emperger , who began his investigations on July 30, 1772 in Gmünd. Eva Kary was interrogated by him on August 10 and 11, 1772 and stated that there must have been a forbidden thing in the snack, but she did not know how it got there. On August 31, 1772, the ban judge then applied to the provincial governor to either release the delinquent or to approve the embarrassing questioning , i.e. the torture. This approval was granted on September 11, 1772 with the condition that a confession should first be obtained by demonstrating the executioner and showing the instruments of torture (fright). On October 27, 1772, Eva Kary was brought into the torture chamber and introduced to her the executioner in his bright red cloak with gold braid and red pointed cap with two slits for eyes, who looked terrible to her. She asked for the executioner and the local assessors to be removed, as she wanted to confess. She confessed that it was through her that the poison got into the lard in which the pasta was toasted. She was interrogated again in the afternoon, but was silent about how the poison was added. Therefore, on December 1, 1772, another application was made to the provincial government for permission to torture, which was granted on January 15, 1773. On February 4, 1773 this was finally carried out and Eva Kary created a "quarter bunch or 6 cord". Under the torture, she finally confessed that she had chopped off a pea-sized piece of the poison, ground it on the stove with a stone, and then sprinkled it in the lard. She did this to get away from her husband. Her husband's stepmother didn't want to kill her, she thought the little poison wouldn't harm her.

The final interrogation on February 6, 1773 did not reveal much that was new. Eva Kary also remarked that the talk of stepmother and housekeeper had also hurt her and contributed to the crime. The statements were confirmed by those named on February 8, 1773. On February 15, 1773 a report was made to the governorate and asked for the judgment, which was passed on February 16, 1773. It was announced to Eva Kary on March 20, 1773 at 9 a.m. According to the applicable court order, she was sentenced to death:

"[..] by the prince. Freymann executed at the usual place of execution through the hardship of life to death, the right hand cut off, head and hand put on the wheel, and the body buried in loco suplicii [at the place of execution], and this for their well-deserved punishment, others but for an example. "

At 8 a.m. on March 21, she applied for clemency to the Empress , whereupon the execution of the death penalty had to be suspended. Your request was rejected by the higher court in Vienna . On November 9th, 1773 she was executed by executioner Martin Jakob at the Gmündner execution site, called Galgenbichl, about two kilometers northeast of the city. Her body was buried at the place of execution, her severed head and right hand were displayed there in warning.

Legal history

The court proceedings followed the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana , the Theresian Neck Court Code , which came into force in 1769 and still provided for torture as part of the court proceedings. This changed little with regard to the court rules in Carinthia, as the ban judge's office had existed there since 1494. A kind of traveling court was designated as a ban judge's office, which had to be called by the many regional courts to carry out blood judicial proceedings, unless the relevant regional court was exempt from this. A distinction was made between privileged and non-privileged regional courts. Privileged regional courts were allowed to judge by their own ban judges in blood jurisdiction. The regional courts under the influence of Counts Lodron , Rauchenkatsch , Gmünd and Sommeregg were all non-privileged regional courts. The spell judge consisted of a spell funnel, a prosecutor, one or more defenders ( procurators or Malefizredner called), a clerk and a executioner (free man). In addition, there were assessors who were appointed by the rulers. The ban judge was appointed by the prince and was subordinate to the governorate and thus the inner Austrian government in Graz. The seat of the ban judge and Freimann was in Carinthia Sankt Veit an der Glan . In 1774 the seat of the ban judge was moved to Klagenfurt , the Freimann stayed in Sankt Veit.

In contrast to the district judges, mostly only semi-skilled civil servants, the ban judges were almost exclusively doctors of law , which ensured compliance with certain minimum standards of the administration of justice . Nevertheless, the ban judge had no great powers of his own; in case of doubt, the consent of the sovereign and thus the governor had to be obtained, which is also evident from the course of the process. In addition, there was a criminal council introduced around 1735, to which four lawyers belonged. The judge's report was presented to this criminal inspector. The governor presided and was not bound by the majority opinion of the council. This council also decided on the conduct of the torture. All those involved in the ban judge commission had to swear to the governor that they carried out their work in accordance with the applicable legal norms , that they would only act on the governor's orders and that they abstained from "all rumor and other carelessness as well as excessive drinking" during the ruling . Violations were severely punished.

From the process of the Faschauerin it can be seen that in an inquisition trial the confession of the accused was of great importance. Torture was also used to obtain a confession. It was believed that an innocent man could endure the torture without confessing. Torture was abolished in Austria by a decree of Maria Theresa in 1776. In Josephine penal code of 1787 she was no longer included.

The execution of Eva Kary was the last at Gmündner Galgenbichl. Before the construction of the Tauern Autobahn , the place of execution was elevated on a curve in Katschberg Strasse , which, as the “Untere Strasse”, has played an important role in the trade in goods across the Alps for centuries . During the construction of the Tauern Autobahn, the Lieser was relocated and the road straightened, making the place of execution disappeared. Today a wayside shrine erected in 1984 commemorates this.

Reviews

In Pöllatal and Rotgülden within 20 km around Malta arsenic degradation and its treatment took place. The possession of arsenic was strictly forbidden, but some farmers in the Gmünd rule had it secretly in their homes. Due to its difficult traceability, murders and attempted murder using arsenic were not uncommon. Only with the Marsh test could arsenic be reliably detected from 1836 onwards. In advance, one usually judged the smell of substances that were dropped on hot charcoal, with arsenic compounds smelling like garlic.

The trial cost the enormous amount of 361 guilders 47 kreuzers . For comparison: a good beef cost about 12 guilders in 1748. The costs had to be borne by the property of the Hörl-Hof, the rest from the Faschauner property.

This criminal case led to the formation of legends. It was said that when Eva Kary was born, the Abschinder , a taboo profession at the time, was professionally present at the Faschaunerhof. He is said to have prophesied the newborn in the horoscope that it was intended for the executioner. Another, often heard legend says that after Eva Kary's death sentence, no farmer lived on the Faschaunerhof. Eva Kary's father Christian Faschauner died in 1777 about three years after his daughter. Eva Kary's half-sister Anna Faschauner married Andreas Berger in 1777, who is referred to in the marriage book as "rusticum [farmer] an der Faschaunerhuben". Their daughter Maria Berger married Josef Pacher in 1802, whose son Thomas Pacher took over the farm from his father in 1824 at the latest. Therefore, at least 50 years after Eva Kary's death, relatives and descendants were still resident at the Faschaunerhof.

Artistic and literary representations, tourism

The story of Eva Kary inspired time and again to deal with the case literarily or artistically. The writer Maria Steurer, born in Eisentratten near Gmünd in 1892, published the novel Eva Faschaunerin in 1950 , which is based on the court files of the case. In 2014 there was a charity event in Gmünd in favor of the Gmünd City Museum with the title Eva Faschaunerin - a musical story with choir and orchestra . In 2016, a theater production called The Process of Eva Faschauner took on the subject. In April 2017, the film The Gift of Freedom by filmmaker Herbert Hohensasser premiered in Gmünd with amateur actors from the region. The direction was initially held by Adi Peichl , who later handed it over to Herbert Hohensasser for health reasons.

The story of Eva Faschauner is also important for tourism. The city of Gmünd named the Museum Eva Faschauner-Heimatmuseum, which was set up from 2006 to 2013, and provided information there, among other things, about the court proceedings.

literature

- Richard Wanner: An Inquisition Trial in Gmünd 1770–1773 . In: Carinthia I . 148th year, 1958, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 672–677 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]). - The author concentrates on the course of the process and relates the conduct of the process at the time to the history of the law.

- Josef Schmid: From popular life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 365–500 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]). - From the minutes of the Rauchenkatsch, Gmünd and Sommeregg regional courts, the author gives an insight into the coexistence in the Lieser and Maltatal valleys of the past, the story of Eva Kary is illuminated from a folklore perspective, with drawings by Paul Kriwetz.

- Maria Steurer: The fate of Eva Faschaunerin . Novel. 2nd Edition. Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 2015, ISBN 978-3-475-54504-7 .

- Georg Lux, Helmuth Weichselbraun: Forgotten & suppressed. Dark places in the Alps-Adriatic region. Styria Verlag, Vienna / Graz / Klagenfurt 2019, ISBN 978-3-222-13636-8 , pp. 20-29 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ births V . Parish Malta, S. 138r , 1st entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

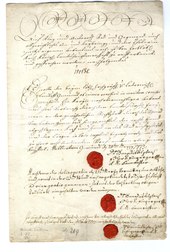

- ^ A b Kärntner Landesarchiv, Lodron, ark 75 fol. 209 ( online )

- ↑ a b Death Book II . Parish Malta, S. 19v , 3rd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Rudolf Waizer: The last justification at Gmünd in 1773 . In: Carinthia . 62nd year, 1872, ZDB -ID 505876-4 , p. 124–127 and 141–146 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Birth Book IV . Parish Malta, S. 85r , 2nd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ birth book . Parish Malta, S. 215r , 3rd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Sterbbuch I . Parish Malta, S. 166v , 6th entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Sterbbuch I . Parish Malta, S. 200v , 4th entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ births V . Parish Malta, S. 63r , 2nd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ births V . Parish Malta, S. 250v , 3rd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ births V . Parish Malta, S. 319r , 3rd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ marriage register B . Parish Malta, S. 8v , 3rd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ births V . Parish Malta, S. 165v , 1st entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Death Book II . Parish Malta, S. 72r , 9th entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Josef Schmid: From people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 475–483 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 476 ( onb.ac.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d e f Richard Wanner: An Inquisition Trial in Gmünd 1770–1773 . In: Carinthia I . 148th year, 1958, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 672–677 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 448 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 472 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Quoted from Rudolf Waizer: The last justification at Gmünd in 1773 . In: Carinthia . 62nd year, 1872, ZDB -ID 505876-4 , p. 143 ( onb.ac.at [accessed April 6, 2020]).

- ↑ a b Martin Wutte : The Carinthian Bannrichteramt . In: Carinthia I . Volume 102, 1912, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 115–136 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Martin Wutte : The Carinthian Bannrichteramt . In: Carinthia I . Volume 102, 1912, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 123 ( onb.ac.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 444–449, 470–473 ( onb.ac.at [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Jan Zopfs: The princes abolish torture. To eradicate torture in Prussia, Austria and Bavaria ( 1740-1806) . In: Karsten Altenhain, Nicola Willenberg (ed.): The history of torture since its abolition . V&R unipress, Göttingen 2011, p. 25 ( google.at [accessed on January 14, 2020]).

- ^ Karl Lax: Excerpt from the history of Gmünd in Carinthia . 2nd, revised edition. Self-published, Gmünd in Carinthia 1950, DNB 574573291 , p. 33 .

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 492 ( onb.ac.at [accessed December 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Armin Hildebrandt: The electoral Bavarian administered Mautoberamt Tarvis: A contribution to the customs, trade and transport history of Carinthia in the 17th century . In: Carinthia I . 160th year, 1970, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 448 ( onb.ac.at [accessed December 16, 2019]).

- ^ Karl Lax: From the chronicle of Gmünd in Carinthia . Ed .: Ilse Maria Tschepper-Lax. 4th edition. Self-published, Gmünd in Kärnten 1987, p. 79 .

- ^ Alfred Pichler: Mining in West Carinthia . Natural Science Association for Carinthia, Klagenfurt 2009, ISBN 978-3-85328-051-5 , p. 97 .

- ↑ Ulrike Mengeú: Gmünd: Surprising discoveries in Upper Carinthia's oldest city . Gmünd City Association, Gmünd in Carinthia 2017, ISBN 978-3-200-05274-1 , p. 148-151 .

- ↑ Theodor Weyl : Analytical auxiliary book for the physiological-chemical exercises of the mediciners and pharmacists in tabular form . Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 1882, ISBN 978-3-662-39491-5 , p. 2 ( google.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Josef Schmid: From the people's life in the Lieser and Maltatal . In: Carinthia I . 154th year, 1964, ISSN 0008-6606 , p. 407 ( onb.ac.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Ulrike Mengeú: Gmünd: Surprising discoveries in Upper Carinthia's oldest city . Gmünd City Association, Gmünd in Carinthia 2017, ISBN 978-3-200-05274-1 , p. 145 .

- ↑ Rudolf Waizer: The last Justifizierung to Gmund in 1773 . In: Carinthia . 62nd year, 1872, ZDB -ID 505876-4 , p. 146 ( onb.ac.at [accessed August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ Frido Kordon: Legends and their places in the Lieser and Maltatale of Carinthia . In: Journal of the German and Austrian Alpine Club . tape 68 , 1937, ZDB -ID 201034-3 , p. 82 ( onb.ac.at [accessed on August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ Death Book II . Parish Malta, S. 86r , 5th entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ marriage register B . Parish Malta, S. 20r , 2nd entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ marriage register C . Parish Malta, S. 102 ( matricula-online.eu [accessed August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ marriage register C . Parish Malta, S. 163 , 1st entry ( matricula-online.eu [accessed on August 4, 2019]).

- ↑ Steurer, Maria, AEIOU. In: Austria Forum, the knowledge network. March 25, 2016, accessed May 1, 2019 .

- ^ "Eva Faschaunerin" benefit event . In: Stadtnachrichten Gmünd . No. 2 / July. City of Gmünd, Gmünd in Kärnten 2014, p. 16 ( stadtgmuend.at [PDF; accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Anna Salzmann: The process of Eva Faschauner . In: My week . June 15, 2016, ZDB -ID 2675776-X ( meinbezirk.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Verena Niedermüller: "Toxic" film premiere in Gmünd . In: My week . April 4, 2017, ZDB -ID 2675719-9 ( meinbezirk.at [accessed on May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Ulrike Wiebrecht: The gloomy story of Eva Faschaunerin . In: Berliner Zeitung . September 9, 2000, ISSN 0947-174X ( berliner-zeitung.de [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Guided tours through the artist town of Gmünd . In: Stadtnachrichten Gmünd . No. 3 / December. City of Gmünd, Gmünd in Kärnten 2012, p. 13 ( stadtgmuend.at [PDF; accessed on May 1, 2019]).

Remarks

- ↑ The exact date is unknown, as the relevant marriage book of the parish of Malta cannot be found.

- ↑ In the past, the two districts of Malta were called Malta Unterdorf or Lower Malta and Malta Upper Village or Upper Malta.

- ↑ During the lacing according to the neck court order of Empress Maria Theresa (1769), the delinquent was placed on a stool (or leaning against a ladder) and his hands (and feet) were gagged with thin ropes. These ropes were pulled together with rollers by two torturers, causing significant pain. During the ladder torture, the body was also extremely elongated. The severity of the torture was measured by the number of lacings.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Faschaunerin, Eva |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Kary, Eva; Faschauner, Eva (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian farmer and convicted murderer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 21, 1737 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Malta , Carinthia |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 9, 1773 |

| Place of death | Gmünd , Carinthia |