Jewish community of Speyer

The Jewish community of Speyer was one of the most important Jewish communities in the empire in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period .

The beginnings in 1084

Towards the end of the 11th century, the first Jewish community emerged on the periphery of the episcopal city . At the work of Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann (also Huozmann) and with the express approval of Heinrich IV. Speyer took in a large number of Jews in 1084 who emigrated or were lured away from Magenza ( Mainz ) and other Rhenish cities.

In the bishop's notes it says: “When I made the village of Speyer a city, I believed that I would increase the reputation of our place a thousand times by including Jews there. I settled the newcomers outside the homes of the other citizens, and so that they would not be so easily alarmed by the insolence of the minor people, I surrounded them with a wall. ”The first settlement took place in the suburb of Altspeyer and was the first documented ghetto In return, the Jews paid £ 3½ in silver and agreed to take part in the defense of the city.

The bishop guaranteed them various rights and privileges that were not customary anywhere in the empire . Accordingly, they could u. a. Trade without restriction, exchange gold and money, acquire property, had their own laws, jurisdiction and administration, did not have to pay tolls or customs duties at the city limits and were allowed to have non-Jews as servants . The reason for the settlement was the important role that Jews played in the lucrative long-distance trade and the desire for a source of finance for the construction of the cathedral . The settlement of Jews was generally viewed as an "economic development measure". The Jews were important pioneers of urbanization in Germany. Riots against the Jews and the hindrance of their trades led to noticeable economic disadvantages and tax losses. Hence it came about that the authorities mostly turned against persecution. By granting privileges and promising special protection, the regents lured Jews into their domain and at the same time tried to protect their extensive tax revenues and protection money ( Judenregal ) from pogrom-related losses.

On the mediation of Bishop Huzmann, Heinrich IV confirmed the privilege of 1084 in 1090 before his third move to Italy and even extended it ("sub tuicionem nostram reciperemus et teneremus"). In doing so, he extended this privilege, initially issued specifically for Jews from Speyer, to all Jews in the empire. This imperial Jewish privilege was one of the first in Germany. The regulations covered various political, legal, economic and religious issues in life. Accordingly, the Jews were allowed to practice free trade, sell their goods to Christians and their property was protected. A new regulation was that stolen property that was acquired by Jews and found on their premises had to be sold back to the original owner at the same price if so desired. This significantly reduced the trading risk, as the popular accusation of stolen goods was countered. In the event of disputes between Jews and Christians, "the law of the person concerned" should apply in the future, i. This means that the Jews were also allowed to prove their rights through oaths or witnesses . Judgments by God may no longer apply. In addition, the Jews were free to turn to the emperor and the royal court in case of difficulties . Disputes between Jews, on the other hand, were allowed to be subject to their own jurisdiction . This was intended to prevent arbitrary convictions by Christian judges. Torture of any kind was strictly forbidden, and the privilege provided for fines to be paid to the emperor in the event of murder or injury.

Baptisms were strictly regulated in privilege . Forced baptisms of Jewish children were completely forbidden. There was a waiting period of three days as a reflection period for voluntary baptisms . Leaving the Jewish religious community was made even more difficult by the fact that the right of inheritance expired in the event of baptism . This baptismal and inheritance regulation was intended to protect the existence of the Jewish community and thus an important source of income. In addition, Jews were allowed to employ Christian maids , wet nurses, and servants in their homes if it was guaranteed that they could keep Christian Sundays and holidays. The Jewish privileges of Henry IV, such as the Worms privilege of the same year, were repeated and modified many times in the following years and shaped the relationship between Jews and Christians over the course of the centuries.

First pogroms in 1096

Six years after issuance of the first privilege certificate for the Jews of the empire occurred in connection with a great plague , which one blamed the Jews, and the First Crusade in Speyer to a first pogrom , which a few days later more riots in Worms and Mainz followed . On his way to the crusade, Count Emicho von Leiningen stopped in Speyer on May 3, 1096 and attacked the synagogue. In a report on the pogroms of 1096 in Speyer and Worms, written around 1097–1140 by the so-called “ Mainz Anonymus ”, it says: “And it happened on the 8th day of the month of Ijar (May 6, 1096), a Sabbath , there the divine judgment began to fall upon us, when the erring and the townspeople had rebelled against the holy men, the pious of the Most High, in Speyer; they advised against them to take them together in the synagogue. They heard this, so they got up early in the morning, even on the Sabbath, prayed quickly, and left the synagogue. And when they (= the enemy) saw that their plan to seize them together was not feasible, they rose up against them and killed eleven souls ... And it happened when Bishop Johann heard this, he came with them great army and stood by the congregation wholeheartedly, he took them into the apartments and saved them from their hands. ”However, the bishop had himself paid for by the Jews for his help.

The bishop had the rebels severely punished and the Jews stayed in the royal and bishop's palace immediately north of the cathedral until the anger of the mob had subsided . This prevented mass murders and expulsions in Speyer , as happened in other cities in the Rhineland ; in the pogroms in Worms and Mainz, also led by Count Emicho, for example 800 and even 1000 Jews were killed. In his chronicle of the persecution of the Jews during the First Crusade in 1096, Solomon bar Simson reports about the pogrom in Speyer around 1140: “In that year the Passover festival fell on Thursday and the new moon of the Ijar on Friday and Sabbath. And on the eighth Ijar, a Sabbath, (May 3rd, 1096) the enemies rose up against the community of Speyer and killed eleven holy souls of them, who had sanctified their Creator on the holy Sabbath, because they were not ready to deal with their stench to let reinforce. There was a respected and pious woman there who slaughtered herself to sanctify the name. She was the first of those who were slaughtered and slaughtered in all parishes, and the rest were saved by the bishop (John I, 1090–1104) without reinforcement, according to everything written above. "

The pogroms in Speyer, Worms and Mainz in 1096 found their way into the Jewish annals as " Gezerot Tatnu " (persecutions of the year 4856) and the victims are still commemorated in the Jewish liturgy today.

Heyday

In the period that followed, Jews were settled not far from the cathedral in the Judengasse / Kleine Pfaffengasse area, although the settlement in Altspeyer continued to exist and where there was a synagogue. At the head of the Jewish community, which was estimated to consist of 300 to 400 people, was the Archisynagogue appointed by the bishop . The center of the settlement was the Judenhof , the cultic center with a synagogue for men and women and the ritual cold bath ( mikveh ). The synagogue and the cathedral were planned and built by the same master builders. The synagogue was inaugurated on September 21, 1104, eight years after the persecution of 1096. Its ruin is still preserved today and represents the oldest, still visible remains of a synagogue house in Central Europe.

The actual Judenbad (first mentioned in 1126) has remained almost unchanged to this day and is one of the oldest preserved facilities of this type. Together with Frisians , the Jews of the 11th and 12th centuries made up the majority of long-distance merchants (negotiatores manentes), both groups being their own Had seats in the merchants' settlement before cathedral immunity . Members of the famous family of rabbis and scholars Kalonymus lived and worked in Speyer (see also The Wise Men of Speyer ). Jekuthiel ben Moses , a liturgical poet, lived in Speyer around 1070. Another Kalonymus from Speyer and a close relative of the highly learned author Eleazar ben Jehuda ben Kalonymus was temporarily responsible for the financial business of Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa and was greatly appreciated by him. In terms of cultural history, Samuel ben Kalonymus he-Chasid and his sons, especially Juda ben Samuel , called Jehuda the Pious, were probably born around 1140 in Speyer, grew up and worked there.

The Jewish community of Speyer was one of the most important in the empire in those years, was an important center for studying the Torah and, despite persecution and expulsion, made a significant contribution to the city's intellectual and cultural life over the centuries. At a rabbinical synod in Troyes , the Jewish communities of Speyer, Mainz and Worms were given the leadership of the Jews in Germany. These communities formed a union called " ShUM ", [ שו"ם ] after the Hebrew initials of Speyer (Schapira, Hebrew : שפירא ), Worms [ורמיזא] and Mainz [מגנצא], which was used by the Jews throughout Germany as an authority in legal matters and religious issues has been recognized. the Shum-cities had their own rite and the decisions of their synagogues, Takkanot Schum , and retained this position until about the middle of the 13th century in. There were several significant Jewish schools and a very popular Talmudic study house. Because of the For the spiritual charisma of the flourishing Jewish communities there, these three cities were celebrated in the Middle Ages as the Rhenish Jerusalem, were of formative importance for Western European Judaism and are therefore considered the birthplace of Ashkenazi culture .

Pogroms and expulsions from 1195

Shortly after the third crusade , persecutions (“ ritual murder ” pogrom) took place again in February 1195 , in which nine Jews were killed. On February 13th, the daughter of the rabbi and judge Isaak ben Ascher Halevi the Younger (* 1130) was murdered on charges of ritual murder and put on display for three days on the market square. Halevi was also killed when he cracked down on the mob that attacked the corpse. The houses of the Jews were burned down and the synagogue in Altspeyer was destroyed.

The riots were repeated in 1282 and 1343. Due to the waves of refugees triggered by the pogroms, King Rudolf I of Habsburg was forced to issue the mandate on fugitive Jews on December 6, 1286 during a stay in Speyer . It says: “Rudolf, by God's grace Roman King, always a member of the empire, offers the wise men, the eunuch, the mayor, the judges, the councilors and all citizens of Mainz, his dear faithful, his grace and all the best. Since the Jews, all as our chamberlains, with all their people and all their possessions, belong to Us in particular - or to those princes to whom these Jews were given as fiefs by Us and the Kingdom - the following is appropriate and correct, indeed completely in accordance with the law: If some of these Jews have fled and ventured across the sea without our or their master's special permission and consent in order to evade their true rule, then we or the masters to whom they belong can with regard to all their possessions, belongings and movable and immovable goods, wherever they can be found, interfere with us lawfully and take them under our power. So that such attempted injustice is directed particularly against these fugitive Jews themselves, We, trusting in the prudence and loyalty of the revered Prince Heinrich Archbishop of Mainz, our beloved secretary, and the noble Lord Eberhard, Count von Katzenelnbogen, give them over all Jews von Speyer, Worms, Oppenheim, Mainz and all Jews of the Wetterau through the present the power of attorney, the possessions, belongings, movable and immovable goods of fugitive Jews, wherever they can find them, without objection from anyone to take under their power and according to theirs To prescribe and dispose of it as they see fit. That is why we ask your loyalty with the utmost emphasis, you would like to endeavor to help and support those named, the archbishop and the count, in the aforementioned so effectively and faithfully that we can then rightly recommend the willingness of your devotion. Given at Speyer on December 6th, in the 14th year of our kingship. "

At the beginning of the 14th century, the power of the emperor and the bishop was weakened and in 1330 the city took over the protection of the Jews in return for payment of 300 pounds sterling, an obligation that it and the bishop failed to fulfill. In the nationwide pogroms at the time of the Black Plague , the Speyer Jewish community was completely wiped out by around 400 members on January 22, 1349. Many burned themselves to death in their homes in the face of the threats; others converted or fled to Heidelberg . Her property and the cemetery were confiscated. In order to legally clarify the breach of the urban order of peace, which was supposed to protect all residents equally, King Charles IV , when he was in Speyer in the spring of 1349, made an opportunistic decision in favor of the city and absolved it of any guilt. The plague epidemic continued into the summer, but nothing is known of its immediate effects on the city. Some Jews were able to flee from the city during this pogrom and return from 1352, were expelled again in 1353, in order to be allowed to return to the city the following year. The move was made to settle the Jews in a permanent residential area in the area of today's Judengasse.

The community never regained the status it had before its destruction in 1349. In the periods between the pogroms and expulsions, the relationship between Jews and the rest of the population remained tense and Jews had to live with many prohibitions and restrictions. For the year 1434 it is documented that the Speyer council renewed the right of residence to the Jews for a further six years, for which 5 to 35 guilders were to be paid per household. But as early as the following year, on May 8, 1435, the Jews were expelled “forever” from the city, presumably under pressure from the citizens. One of the refugees was Moses Mentzlav. His son, Israel Nathan founded a printing company in Soncino .

Modern times

For 1467 it is again documented that the city took Jews living in the city under its protection for a further ten years and that it stood up for them with the bishop because he had special powers to regulate the personal living conditions of the Jews. In 1468, 1469 and 1472, Bishop Matthias von Rammung issued ordinances, according to which the Jews did not have to live scattered in the city, but together, and they were allowed to have a synagogue in Speyer. In addition, they had to clearly distinguish themselves from Christians in terms of their clothing: as decided at the Lateran Council of 1215, men had to wear pointed hats of different colors and a yellow ring on their chests. However, there are Speyer documents from the middle of the 14th century on which Jews are depicted with pointed hats. Jewish women had to have two blue stripes in their veils as identification. They were not allowed to participate in Christian public societies, have no Christian servants, employ midwives, sell medicines or engage in usurious business. During Holy Week and on major public holidays, Jews were not allowed to appear in public and had to keep doors and windows locked. In 1472, many Jews committed suicide to avoid forced baptism . From 1500/1529 no more Jews lived in Speyer.

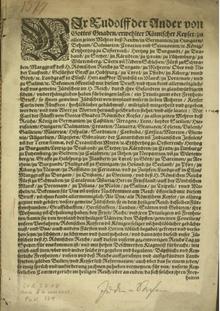

The "Great Speyr Jews' Privilege" from 1544

At the Reichstag in Speyer in 1544, the Jews of the empire complained to Emperor Karl V that they were being mistreated and denied their rights. It was enumerated that they were "tremendously, fravernally and voluntarily abused and complained of their people, love, haab and gods with killing, robbing, driving away, driving away their ugly apartments, blocking and destroying ier shuffling and sinagogues, and complaining of the same to belait and pay off" that they were prevented from earning their livelihood and that they were prevented from appealing to the Imperial Court of Justice or other courts. In addition, the Jews in some cities of the empire were "not horrified, captured and driven out of the country, but also caught, tormented, exterminated and belly and guett" without any legal discomfort. The trigger for the increasing disregard for the rights of the Jews were, among other things. a. the well-known anti-Jewish writings of Luther from 1543.

Emperor Karl felt compelled to renew the protection of the Jews and the confirmation of their privileges. No one should henceforth have the right to close their schools and synagogues, to drive them out of them, or to prevent them from being used. Anyone who violates or robbed Jews of life or property in contravention of the proclaimed imperial peace in the country should be punished by every government. Every Jew should have the right to go about his business in the empire, and every government should grant him escort and no longer burden him with customs or tolls. The Jews were not obliged to wear “Jewish symbols” outside their places of residence and no Jew should be expelled from his place of residence without the express consent of the emperor. Since Jews were taxed more heavily, but they had neither lying goods nor “static handtierung, ampter or handicrafts” and could only pay the taxes from “so sy von ieren parrschafften”, they were allowed to “make pairing” and interest [...] umb soill the higher and about further and more, then the cristen is allowed to invest ”. Without sufficient evidence and witnesses, anyone was forbidden to accuse Jews of using Christian blood or to arrest, torture or execute them because this suspicion had already been rejected by the popes and prohibited by a declaration by Emperor Frederick. Where such accusations were made, they were to be brought before the emperor. Violations of this privilege were to be punished with 50 marks of soldered gold, half of which should go to the imperial treasury and half to the damaged Jews.

In 1548 these privileges were confirmed again by Charles V himself and in 1566 by Emperor Maximilian II.

17th, 18th and 19th centuries

A Jewish community existed again temporarily from 1621 to 1688. During the Thirty Years 'War and especially in the post-war period, the indebted cities and Christian fellow citizens were increasingly forced to make use of the Jews' ability to pay and take out loans. Between 1645 and 1656 there are at least five such loans between citizens. The city began to take out loans from Jews as early as 1629 and as the debt load increased, there were repeated borrowings and the granting of city trade rights, which were briefly restricted several times as a result of complaints from the guilds during the 17th century. Until Speyer was burned to the ground in 1689 in the Palatinate War of Succession , trade and financial transactions between citizens and Jews were completely banned. Even during the subsequent reconstruction, Jews were no longer allowed to settle permanently in Speyer.

With the French Revolution , a Jewish community emerged in Speyer again from the end of the 18th century, which was characterized by its liberal and emancipated attitude and thus repeatedly came into conflict with the orthodox district rabbinate Dürkheim-Frankenthal . In 1830 it had 209 members. Its center was the synagogue built in 1837 on the site of the Jakobskirche on Heydenreichstrasse. When the city took numerous measures to support the needy during the decades of great poverty, the Jews founded their own charity in 1828 . They also ran their own small school. The community nevertheless took part in the general collections in the city and tried to integrate.

In 1863, Carl David was elected as the first Jewish member of the community council. The Nestor of the Speyer Jews, Sigmund Herz, sat on the city council from 1874 until the eve of the First World War .

In 1890 there were 535 Jews in Speyer. This was the highest level that the Jewish community in Speyer ever had. By 1910, their number had fallen to 403. From the early thirties, Jews from Speyer began to migrate to larger cities or to emigrate entirely because of the constantly growing anti-Semitism .

The Jewish community in the 20th century until today

In 1933 the number of Speyer Jews was still 269 and fell to 81 by the November pogroms in 1938 , when the synagogue was burned down. On October 22, 1940, 51 of the 60 remaining were transferred to the internment camp Camp de during the Wagner-Bürckel campaign Gurs (southern France) deported. From there some of them were able to escape to Switzerland, the USA and South Africa with local help; another part was extradited to Germany by the Vichy government and murdered in Auschwitz. Only one Jew survived the Nazi era in hiding in Speyer.

The synagogue was cleared and set on fire by SA and SS men on the night of November 9th, 1938, and the library, valuable clothing, carpets and ritual objects were stolen. The fire brigade only made sure that the flames did not spread to the neighboring buildings. With the synagogue, the community also lost the classroom for the Jewish primary school. The Jewish cemetery was also devastated that night. The next day the ruins were demolished and the costs were offset against the city's debts to the community. As a replacement, the congregation initially received a prayer room in a member's house on Herdstrasse. After the deportation of the Jews, the city stored their furniture there.

In 1951 the city considered creating a parking lot on the synagogue site. In 1955 the city council decided to pay DM 30,000 to the Jewish community to settle the restitution proceedings . In 1959 the company Anker bought it to complete an area for a department store in Maximilianstrasse. In 1961, on the recommendation of the German Association of Cities, the city took part in a development loan from the State of Israel with DM 2,000.

In 1968 a plaque commemorating the fate of the Jewish community was unveiled in the wall in the courtyard of the Jewish bath . In 1979, after 40 years, another memorial plaque was attached to the rear wall of the Kaufhof building (square of the former synagogue) with the text: The synagogue of the Jewish community of Speyer stood here until it was destroyed by the National Socialists on the night of 9-10 November 1938. Directly in front of this place a memorial was erected in 1992 and a little later moved to the small square (parking lot) opposite. An application by the SPD in 2007 to use small, cobblestone-sized memorial stones, so-called stumbling blocks , in the sidewalk in front of the last homes in memory of Speyer Jews , did not find a majority in the city council.

Until the 1990s there was no longer a Jewish community in Speyer. In October 1996 ten Jews from Eastern Europe decided to found another Jewish community in Speyer. As the Jewish Community Speyer eV, the community received the status of a non-profit association. Schmuel Tepman became chairman; after his death, his granddaughter Juliana Korovai took over the chairmanship. Ignatz Bubis , the chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, supported and advised the association until his death in 1999. The recognition as a public corporation sought by the association was rejected by the regional association of Jewish communities in Rhineland-Palatinate and the state of Rhineland-Palatinate . There were several legal proceedings for the recognition of an official community status for the association as well as for the payment of subsidies by the state of Rhineland-Palatinate to him, whereby he was ultimately defeated.

The foundation stone for a new synagogue in Speyer was laid on November 9, 2008. It was built on the site of the former St. Guido church and offers space for around 100 believers. Construction began in 2010. The Beith-Schalom synagogue ( House of Peace ) was inaugurated on November 9, 2011, 73 years after the pogrom night in 1938. It is used by the Jewish community of the Rhine Palatinate , which is moving its headquarters from Neustadt to Speyer Has. Community rabbi was initially Seew-Wolf Rubins. The religious community has made the joint use of the synagogue by the Jewish community of Speyer conditional on it joining the cultural community of the Rhine Palatinate.

Jewish Cemetery

The medieval Jewish cemetery was opposite the Judenturm to the west of the suburb Altspeyer, which was formerly also inhabited by Jews (today between Bahnhofstrasse and Wormser Landstrasse). After the pogroms of 1349 it was plowed up and the city gave part of the area in 1358 to individual Jews on long leases. After the expulsion of 1405 the area fell to a Christian, in 1429 the Jews were able to dispose of it again. After the expulsion in 1435, the city confiscated the site and leased it to Christians. In the 18th century, the Elendherbergsacker was located on it . After Jews settled in Speyer again in the 19th century, a new Jewish cemetery was laid out on St. Klara-Kloster-Weg, which was used until 1888. The former mourning hall and part of the western wall are still preserved next to the house at St.-Klara-Kloster-Weg 10. In 1888, a new Israelite cemetery was set up in the southern area of the new municipal cemetery in Wormser Landstrasse, where Jews were buried until 1940. This cemetery area is used again today by the Jewish community.

See also

literature

- The Jews of Speyer (= contributions to the history of the city of Speyer; 9). 3. Edition. Historical Association of the Palatinate, Speyer District Group, Speyer, 2004.

- Johannes Bruno : Fates of Speyer Jews 1800–1980 (= series of publications of the city of Speyer, volume 12). Speyer 2000, ISSN 0175-7954

- Johannes Bruno, Lenelotte Möller (ed.): The Speyerer Judenhof and the medieval community. Speyer Tourist Office. Speyer 2001

- Johannes Bruno: The Wise Men of Speyer or Jewish Scholars of the Middle Ages (= series of publications of the city of Speyer, Volume 14). Speyer, 2004, ISSN 0175-7954

- Johannes Bruno, Eberhard Dittus: Jewish life in Speyer. Invitation to a tour . Haigerloch 2004.

- Johannes Bruno: The memorial for the Jewish victims of the Nazi persecution 1933–1945 (= series of publications of the city of Speyer, 16). 2008

- Johannes Bruno: Fates of Speyer Jews II 1800–1980. Verlagshaus Speyer, Speyer 2011, ISBN 978-3-939512-31-8

- Ferdinand Schlickel : Topic on Saturday: Synagogue destroyed 60 years ago. - Inferno in the middle of the city - silence in the newspapers, silence in the town hall. In: The Rheinpfalz- Speyerer Rundschau of November 7, 1998

- Edgar E. Stern: The Peppermint Train: Journey to a German-Jewish Childhood . University Press of Florida, 1992, ISBN 0-8130-1109-4 .

Web links

- Jewish community of the Rheinpfalz , official website

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Stefan Leßmann: The emergence of chamber servitude of the Jews. (pdf, 146 kB) In: s-lessmann.de. April 19, 2006, p. , accessed on January 22, 2019 (term paper in the seminar “The Jews in Europe up to the 12th Century”, WS 1997/98).

- ^ Mary Fulbrook: A Concise History of Germany. Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-521-83320-5 , p. 20.

- ^ Alfred Haverkamp: Deutsche Geschichte , Vol. 2. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich, 1993, ISBN 3-7632-2992-2 , p. 338.

- ↑ a b Gabriel Miller: Jurisdiction over Jews. In: Jewish law. Retrieved January 22, 2019 .

- ^ The great Jewish privilege of Emperor Karl V, given in Speyer, April 3, 1544. In: Digital Archive Marburg - DigAM Project: Exhibition: Privileges, Pogroms, Emancipation: German-Jewish History from the Middle Ages to the Present. Transcription by Christian Siekmann, accessed on January 22, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c 1096 May 3, Emicho (Emico), Count of Leiningen (Germany). In: jewishhistory.org.il. Retrieved January 22, 2019 .

- ↑ a b The great Jewish privilege of Emperor Karl V, given at Speyer, April 3, 1544: Regest. In: Digital Archive Marburg - DigAM Project: Exhibition: Privileges, Pogroms, Emancipation: German-Jewish History from the Middle Ages to the Present. Quoted from Uta Löwenstein: Sources on the history of the Jews in the Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg 1267–1600 , Vol. 1. Wiesbaden 1989, pp. 393–394, accessed on January 22, 2019 .

- ^ A b Walter Saller: Jews in the Middle Ages: Baptism or Death. In: Geo Epoche November 20 , 2005, archived from the original on March 29, 2010 ; accessed on January 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Ferdinand Schlickel: Speyer: From the Salians to today. Hermann G. Klein Verlag, Speyer.

- ↑ s. on this: Elmar Worgull : Views of the vita and museum works of the wood sculptor Otto Martin (1872–1950) who worked in Speyer . In: Pfälzer Heimat: Journal of the Palatinate Society for the Promotion of Science in conjunction with the Historical Association of the Palatinate and the Foundation for the Promotion of Palatinate Historical Research . Publishing house of the Palatinate Society for the Advancement of Science, Speyer. Issue 1 (2009), pp. 19-26.

- ^ Alfred Haverkamp: Deutsche Geschichte , Vol. 2. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich, 1993, ISBN 3-7632-2992-2 , p. 339.

- ↑ Speyer: medieval Judenbad, synagogue and Judengasse. In: alemannia-judaica.de . February 21, 2014, accessed January 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Rudolf I von Habsburg: Mandate on fugitive Jews from December 6, 1286. In: Website by Oliver H. Herde. Retrieved January 23, 2019 .

- ↑ 1349 January 22, Speyer (Germany). In: jewishhistory.org.il. Retrieved January 23, 2019 .

- ^ A b Moisi Haug-Moritz: communication space imperial cities. In: historicum.net. May 12, 2006, accessed January 23, 2019 .

- ^ History of the City of Speyer , Vol. 2. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart, 2nd edition, 1983, ISBN 3-17-007522-5 , pp. 21-22, 150.

- ^ Wolfgang Eger: History of the City of Speyer , Vol. 3. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1989, ISBN 3-17-010490-X .

- ↑ Christoph Schennen: "Project takes on the form that was planned from the start": Gunter Demnig presents his project "Stolpersteine" in the Heiliggeistkirche. In: speyer-aktuell.de. October 24, 2016, accessed January 23, 2019 .

- ^ The history of the Jews in Germany: Speyer. haGalil , December 29, 2013, accessed April 8, 2015 .

- ^ Helmut-Weiß: On the way to the "Project Speyer". In: The Rhine Palatinate . November 24, 2000, accessed April 9, 2015 (reproduced on haGalil).

- ↑ Johann L. Juttins: “We are no longer alone!” In: Jüdische Zeitung . March 15, 2010, accessed on January 23, 2019 (reproduced on haGalil).

- ↑ a b Land does not pay any money in the Speyer community: recognition refused. In: Jüdische Allgemeine . January 16, 2013, accessed January 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Rabbinate. Jewish community of the Rhine Palatinate, archived from the original on April 8, 2015 ; accessed on January 23, 2019 .

-

↑ History needs faces: Johannes Bruno portrays Jews from Speyer. In: speyer.de. Archived from the original on December 18, 2011 ; accessed on January 23, 2019 . Fates of Speyer Jews from 1800 to 1980 (Volume 12). In: speyer.de. Retrieved January 23, 2019 .

- ^ The Wise Men of Speyer (Volume 14). In: speyer.de. Retrieved January 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Anja Stahler: 17 Life Against Forgetting. In: Die Rheinpfalz , Speyerer Rundschau, November 7th 2011, page 2 LSPE.