Corinthian Covenant

The Corinthian Covenant was a 337 BC. Confederation of states founded in ancient Greece , which included almost all Greek city-states . In it the Macedonian hegemony under Philip II and Alexander the Great over Greece had manifested itself under constitutional law. In 302 BC It was renewed by Demetrios Poliorketes during the Diadoch Wars , but this revival did not last longer than a year. The contemporary name of the covenant was simply "Bund der Hellenen" ( koinon tōn Hellēnōn ), while it is named in modern historical literature for better differentiation after the meeting place of his council on the Isthmus of Corinth .

background

The need of the ancient Greeks, split up into several city-states ( poleis ) and at war with each other, for political unity ( homonoia ) and general peace ( koinē eirēnē ) among themselves had played a prominent role throughout their history, especially in view of the fact that all Greeks since the Persian Wars as Arch enemy considered the Persian Achaemenid Empire . Several attempts at a permanent agreement failed because of the rivalries with each other, with the three most important city-states Athens , Sparta and Thebes in particular fighting each other in several wars because of their competition for supremacy over the Greeks ( hegemony / hēgemonía tēs Hellados ). In the 4th century BC alone They broke the peace of the land that had previously been sworn at least six times. This discord was encouraged by the great Persian kings through financial or military aid, which the Greeks accepted despite their declared hostility. In the 4th century BC, guided by the statesmanlike and military skill of its King Philip II , Macedonia was able to establish itself as a power-political force in the struggle for hegemony, benefiting from the resources of a state and its state organization, as a kingship endowed with absolute powers ( monarchia ).

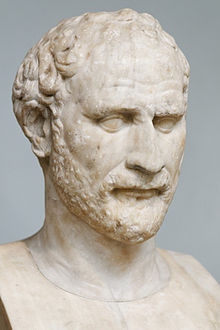

Philip II strove to subjugate the Greeks to his hegemony, as their leader he finally wanted to carry out the campaign against the Persians. He allowed himself the legitimacy of this claim after the end of the third holy war in 346 BC. From the Delphic Amphictyony , in which he had just established Macedonia. Following the laws of the time, those Greek cities that themselves claimed the hegemonic position opposed his plan. With the increasing power of Philip II, this conflict was accompanied by an intensified propagandistic campaign on the part of the Greeks, in which above all personalities such as Demosthenes denied Hellenism to the Macedonians and their king and this people, due to their supposed cultural inferiority and their seemingly archaic state, denied Hellenism Persians viewed more as barbarians to whom any submission was forbidden. On the other hand, a Macedonian hegemony found its supporters among the Greeks, such as Aristotle and Isocrates . Under the dominant influence of Demosthenes, Athens presented itself in 340 BC. At the head of a newly founded Hellenic League, which was supposed to curb the power of Philip. 339 BC Thebes finally joined this union, but the following year the armed forces were defeated in the decisive battle at Chaironeia against Philip, whereupon the union broke up immediately. Apparently it was institutionally not deepened, since Philip concluded a separate peace with each individual member.

founding

After his victory Philip put a Macedonian garrison in the city castle of Thebes, the Kadmeia , and then moved across the Isthmos to the Peloponnese , where he contractually assured the benevolence of the cities there and demonstrated his strength to Sparta . Thereupon he withdrew to the isthmos, where in the summer of 337 BC. Following his call to Chaironeia, the representatives of almost all Greek cities, with the exception of Sparta, arrived on the Isthmus of Corinth to begin the deliberations on the formation of a new Hellenic League in the sanctuary of Poseidon . The choice of the conference location was probably no coincidence, because 481 BC had come here. The Greeks gathered together under Xerxes I to form the first Hellenic League to ward off the Persians . The retribution of the desecration of temples by the Persians at that time as well as the liberation of the Ionian Greek cities in Asia Minor , which they ruled , was now propagated by Philip as the primary motive for the formation of a new Panhellenic league, which he wanted to preside over as a hegemon.

This program, which was directed against the arch enemy of all Greeks, was undoubtedly the reason for the enormous breadth of the group of participants that had never existed in earlier political associations of the Greeks. In fact all cities and city leagues were represented in Corinth, even those of the more peripheral free Aegean islands and the Thracian colonies. Only Sparta stayed away from the League. It was 386 BC. BC concluded the highly controversial royal peace with the Persians , in which the Ionian Greek cities had been ceded to Persia, but which was now actually denounced by the new covenant. From inscriptions and historical traditions can Akarnania , Ainianien , Achaia , Aetolia , Ambracia , Arcadia , Argos , Athamania , Athens , Viotia , Cephallenia which Chalkidiki , the Chersonesos , Corcyra , Corinth , the Cyclades , Dolopien , Doris , Elis , Euboea , Lokris , Magnesia , Malis , Megara , Oitaien , Perrhaibien , Phokis , Phthiotis , Samothrace , Thasos , the Thessalian Islands, Thessaly , the Thracian colonies and Zakynthos are identified as federal members.

Macedonia, like its king himself, was not a full member of the league; Philip II's position as hegemon was regulated between him and the league by an alliance treaty ( symmachia ), legitimized by his election as the military leader of the Greeks ( strategōs autokratōr ) against the Persians .

organization

As in all previous confederations, the principles of general peace ( koinē eirēnē ) formed the basis of the federal treaty in the Corinthian Confederation . This included a general ban on violence between the federal members on land and at sea, the mutual recognition of internal autonomy and the inviolability of constitutional self-determination. Free shipping was guaranteed and a ban on piracy , as well as a property and property guarantee , was established. The office of the hegemon was linked in personal union with the Macedonian kingship, which was to remain hereditary within the royal family. No federal member was allowed to influence the internal constitution of Macedonia and its succession to the throne, just as the hegemon had to respect the internal autonomy of the members. The contracting parties were exempt from paying tributes to the federal government or the hegemon, but were obliged to comply with the federal regulations and their defense against breaches of contract and third parties, as well as to comply with the resolutions ( dogma ) issued by the Federal Council and the instructions of the hegemon. Each federal member had to swear these contractual principles to the gods in a fixed oath.

The oath is almost completely preserved in an inscription on the Acropolis of Athens :

| row | text | Translation after Ernst Badian and Robert K. Sherk |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ․․․․․․․․․․․․ 26 ․․․․․․․․․․․․ Ι․․6 ․․․ | "I swear by Zeus, Ge, Helios, Poseidon, Athena, Ares and all gods and goddesses: |

| 2 | [․․․․․․․․․ 21 ․․․․․․․․․․ Ποσ] ειδῶ ․․5 ․․ | |

| 3 | ․․․․․․․․․․ 22 ․․․․․․․․․․ ς ἐμμεν [ῶ ․․․․] | |

| 4th | ․․․․․․․․․․ 22 ․․․․․․․․․․ νον [τ] ας τ ․․․․ | |

| 5 | [․․․․․․․․ 18 ․․․․․․․․ οὐδ] ὲ ὅπλα ἐ [π] οί [σω ἐ] - | I will adhere to the contract permanently and not violate it [even in details]. [...] I will not take up arms with hostile intentions against those who keep their oath of obligations, either on land or at sea. I will not occupy a city, a fortress, or a port with the intention of waging war. I am not going to arrest any of those who take part in this peace treaty in any way or arrest them by war. Likewise, I will not seek to remove neither the royal rule of Philip and his descendants nor the constitutions that existed in the individual participating states at the time of the oath of conclusion of this peace treaty. Personally, I will not do anything in any way that is contrary to this treaty and will not allow anyone else to do so, as far as it is in my power. |

| 6th | [πὶ πημονῆι ἐπ 'οὐδένα τῶν] ἐμμενόντ [ω] ν ἐν τ- | |

| 7th | [οῖς ὅρκοις οὔτε κατὰ γῆν] οὔτε κατὰ [θ] άλασ- | |

| 8th | [σαν • οὐδὲ πόλιν οὐδὲ φρο] ύριον καταλήψομ- | |

| 9 | [αι οὔτε λιμένα ἐπὶ πολέ] μωι οὐθενὸς τῶν τ- | |

| 10 | [ῆς εἰρήνης κοινωνούντ] ων τέχνηι οὐδεμι- | |

| 11 | [ᾶι οὔτε μηχανῆι • οὐδὲ τ] ὴν βασιλείαν [τ] ὴν Φ- | |

| 12 | [ιλίππου καὶ τῶν ἐκγόν] ων καταλύσω ὀδὲ τὰ- | |

| 13 | [ς πολιτείας τὰς οὔσας] παρ 'ἑκάστοις ὅτε τ- | |

| 14th | [οὺς ὅρκους τοὺς περὶ τ] ῆς εἰρήνης ὤμνυον • | |

| 15th | [οὐδὲ ποιήσω οὐδὲν ἐνα] ντίον ταῖσδε ταῖς | But should anyone do something that violates the contract, I will, in accordance with the terms of the contract, help those who are violated and wage war against those who violate the terms of the contract, in accordance with what the general federal assembly decides and the Hegemon [i.e. the King of Macedon] orders. I will not leave the common cause. " |

| 16 | [σπονδαῖς οὔτ 'ἐγὼ οὔτ' ἄλ] λωι ἐπιτρέψω εἰς | |

| 17th | [δύναμιν, ἀλλ 'ἐάν τις ποε̑ι τι] παράσπονδ [ον] πε- | |

| 18th | [ρὶ τὰς συνθήκας, βοηθήσω] καθότι ἂν παραγ- | |

| 19th | [γέλλωσιν οἱ ἀεὶ δεόμενοι] καὶ πολεμήσω τῶ- | |

| 20th | [ι τὴν κοινὴν εἰρήνην παρ] αβαίνοντι καθότι | |

| 21st | [ἂν ἦι συντεταγμένον ἐμαυ] τῶι καὶ ὁ ἡγε [μὼ] - | |

| 22nd | [ν κελεύηι ․․․․․ 12 ․․․․․ κα] ταλείψω τε ․․ |

To enforce the federal treaty, to defend against third parties and to provide military support to the hegemon in the event of a declaration of war against third parties, the federal government committed itself to providing 20,000 infantrymen and 1,200 cavalrymen. The war against a third party, namely Persia, was decided at the first session of the Bundestag, which included the liberation of the Greek cities in Asia Minor and the retaliation of the desecration of temples in 480 BC. Had its declared goal.

In the Poseidon sanctuary near Corinth , the federal government installed a regular council, the koinon synhēdriōn , which was composed of delegates from the member states whose share of the vote was determined in relation to their military contribution. He was responsible for monitoring compliance with the federal treaty, ascertaining violations and, if necessary, imposing sanctions against contract breakers. In cases of conflict, it acted as an arbitrator or delegated judicial powers to a federal member. Formally, the Synhedrion was the highest constitutional organ of the Corinthian League, which could commission the hegemon with the execution of its resolutions. In fact, however, the hegemon was able to act as ruler over the federal government by virtue of the powers granted to it as a military guarantor of the peace order. The questions to be discussed were defined and presented by him at his discretion. The Synhedrion could either agree to them or not, with the hegemon's military dominance ensuring that decisions were made in its favor. The judgment on the destruction of Thebes in 335 BC serves as an example . BC, the 332 BC Chr. Alexander determined processes against the Persian friends from Chios as well as the sanctions decided against enemies fighting on the Persian side. Outwardly, the hegemon could appear as a tool of the Synhedrion, while this relationship actually behaved in reverse. The military dominance of the hegemon was, with the deliberate omission of a documented freedom of occupation, ensured by the presence of Macedonian garrisons in Thebes, Corinth, Ambrakia and probably also in Chalkis , which, as “shackles for Hellas”, made it virtually impossible to act against his interests. The Corinthian Confederation hardly fulfills the criteria of a federation , i.e. a confederation of states founded on a voluntary basis and under the same conditions of its participants.

The covenant under Philip II

Already at the first session of the Bundestag in the summer of 337 BC In BC Philip II was elected supreme general ( strategōs autokratōr ) and empowered to lead the fight against the Persians. In the same year, an advance command under its generals Parmenion , Attalos , Kalas and Amyntas crossed to Asia Minor, who were able to advance as far as Magnesia on the meander and liberate some Greek cities in an initial offensive . This troop, however, consisted exclusively of Macedonian units and Greek mercenaries, federal troops were not involved in it. A Persian counter-offensive under the Greek mercenary officer Memnon of Rhodes threw the Macedonians back into the Troas , where they barricaded themselves in fortified positions on the local coast, which were to serve as bridgeheads for the main army, which was soon to follow.

Before Philip was able to take up the Persian campaign with the main force, he was in 336 BC. Murdered during the wedding celebrations of his daughter Cleopatra in the theater of Aigai . The creation of the Panhellenic League is generally considered to be his most important statesmanship, which, however, was called into question by his untimely death following the principles of ancient Greek history. Ultimately, only a strong hegemon could guarantee the cohesion of a confederation of states, which now threatened to fail with the succession battles that were to be expected in the Macedonian royal family.

The covenant under Alexander / Antipater

At the news of Philip's death, the supporters of the anti-Macedonian factions in the Greek cities, which traditionally insisted on autonomy, above all in Athens, rose up to defeat the Confederation. They accepted the breach of the recently sworn peace. The old Macedonian enemy Demosthenes established secret contacts with the general Attalus, operating in Asia Minor, who was a personal arch enemy of Alexander and who was now to be called upon to revolt against him. Demosthenes had clearly violated the federal treaty, which clearly forbade outside influence on the Macedonian succession to the throne. Furthermore, the Aitolians decided to return the exiles from Akarnania, who had been driven out by Philip, to their homeland, the Ambrakiats and Thebans intended to drive out the Macedonian garrisons, and in the Peloponnese Argos and Elis decided to restore their independence. Alexander quickly mastered the situation by securing his successor by assassinating Attalus and then moving with the Macedonian army to Boeotia near Thebes. There he was first confirmed in the rights of his father by the Delphic Amphictyony in order to receive a delegation of Athens, to which Demosthenes did not belong, but which declared the loyalty of their city to him. The Greeks were so persistently surprised by his quick action that they had no choice but to take part in the new Bundestag convened in Corinth, where they confirmed the existing treaties, recognized Alexander as the new hegemon and authorized him to lead the Persian campaign.

This did not silence the opposition, which now mainly gathered around Demosthenes and his follower Lykurgus in Athens. In the spring of 335 BC, the cause for a renewed survey. BC Alexander started the Balkan campaign to subdue apostate barbarian tribes. In public speeches in Athens Demosthenes announced the death of Alexander in battle and with it the expiry of the treaties with him. Financed by 300 talents of Persian gold, the Attic enemies of the Macedonians, again breaking the treaty provisions, supported their Theban comrades in their takeover of power in Thebes, who then besieged the Macedonian occupation on the Kadmeia. In August 335 BC However, Alexander appeared with army power after a forced march from Illyria into Boeotia, whereupon the opposition collapsed again when Athens, under the influence of the promakedons around Phocion and Demades, gave up its support for Thebes. The leaders of the Thebans themselves intended to continue the fight despite their political isolation, but were defeated in the Battle of Thebes and their city was occupied by the Macedonians. Alexander entrusted the further fate of this venerable Greek city to the judgment of the representatives of the synhedrion who were present, who ordered the destruction of the city for breaking the koiné eiréne and the enslavement of its inhabitants. Despite its well-known involvement in this survey, Athens escaped a federal execution, in that the city leaders passed it off as a private action by Demosthenes and Phocion and Demades appeared as guarantors for the federal allegiance of their city. Ultimately, Alexander was satisfied with the banishment of some of Demosthenes' supporters and probably with his personal oath of the federal treaty.

After the uprising was suppressed and the federal order restored, Alexander retreated to Macedonia to start the final planning of the Asian campaign . At Amphipolis he called in 334 BC. His main force ( see main article: Army of Alexander the Great ), which now also belonged to a contingent of 7000 infantrymen and 600 cavalrymen of the Hellenic League. If you consider the magnitudes mentioned by Justin, which the federal government had to provide in the event of war, his contribution to the revenge on the Persians so often propagated by the Greeks was downright modest. Alexander had probably not insisted on a higher contribution either, in order not to have to rely on the rather dubious loyalty of the Greeks in an emergency in the battle. Their significance for the struggle, which was mainly waged by the Macedonian troops of Alexander, was of little consequence. In case of doubt, the federal troops carried along could stand hostage for the loyalty of their hometowns and they were sufficient enough to satisfy the claim of a Panhellenic campaign of revenge. According to Arrian , Alexander also knew how to stage this claim in a propagandistic way when he sent armor ( panoplia ) captured from the Persians in 334 as a consecration gift for Athene Parthenus on the Acropolis , in reparation for the 150 years of the Persians previously committed desecration of their temple, which was used as the main motive for the campaign of revenge. He had the armor marked with the following inscription:

"Ἀλέξανδρος Φιλίππου καὶ οἱ Ἕλληνες πλὴν Λακεδαιμονίων ἀπὸ τῶν βαρβάρων τῶν τὴν Ἀσίαν κατοικούντνν.“

The maritime contribution to be made by the Greeks was more important for the Asian company, since Macedonia itself did not have a large fleet. The federal government made a total of 160 ships available for the army to cross the Hellespont and for the subsequent siege of Miletus , in which Athens, still the largest Greek naval power, participated with only 20 ships. After the siege of Miletus, the fleet was disbanded not least for cost reasons, which favored the Persian side in the Aegean Sea. In the spring of 333 BC It was then restored, after which some Aegean islands were liberated.

Since Alexander led the campaign personally, it was necessary to regulate an adequate regency in Macedonia and representation in the hegemony. Both tasks were entrusted to Antipater , who had already been a long-time confidante of Philip II and who had already taken over the affairs of state in Macedonia on several occasions. As military commander-in-chief in Europe ( stratēgōs tēs Eúrōpēs ) an armed force of about 12,000 infantrymen and 1,500 cavalrymen was put at his side, with which he was supposed to maintain the necessary pressure against the federal Greeks. Nevertheless, in the absence of Alexander, a renewed weakening of the hegemonic power was suspected. This time from Sparta, a foreign power which perceived the Bund as an obstacle to its own hegemonic claims in the Peloponnese. Already in the first year of the Persian campaign, Sparta under Agis III. started his military activities against Macedonia, which in the words of Alexander became known as the " mouse war ". For this, Sparta sought the alliance with the Persian great king Dareios III. and the support of his fleet operating in the Aegean Sea, but apart from financial support from the Persians, with which a mercenary army could be recruited, these alliance efforts had no further-reaching consequences. Within the Corinthian Covenant, however, the uprising of Sparta evoked similar reactions as after Philip's death. In Athens, the Macedonian enemies around Demosthenes were able to force the termination of the treaties, the mobilization of the fleet and the start of alliance talks with Persia in the people's assembly ( Ekklesia ). In the Peloponnese, the Spartans succeeded with a proclamation of freedom to persuade the Eleans and most of the Arcadians and Achaeans to change sides, but important cities such as Megalopolis , Argos and Corinth , all of Sparta's old arch enemies, refused and remained loyal to the Confederation. The anti-Macedonian front was shaken by Alexander's victory in the Battle of Issus , as Persia was now no longer a potential ally. As Antipater in autumn 331 or spring 330 BC With an army of 40,000 men, which also included federal troops, moved through Boeotia and over the Isthmos to the Peloponnese, Athens lost its will to fight in the face of this power and, like a few years earlier, left its ally in the lurch. The Spartians were finally defeated in the battle of Megalopolis and their king Agis III. killed.

Antipater had fifty distinguished hostages from defeated Sparta as a guarantee for the future ceasefire, but he delegated the further modalities of negotiating a peace to the Synhedrion in Corinth, as Alexander had already done in the case of Thebes. The council demanded financial compensation from Sparta for the damage done in the war, but in order to negotiate a peace they referred the city directly to Alexander, who was in Asia, in the form of a penitential delegation. This was necessary because the hegemon alone represented the federation externally and could therefore act contractually vis-à-vis a third party, in this case Sparta, while the decision-making authority of the Federal Council was limited to federal members. Nothing is known of sanctions against the apostate members, although Athens' betrayal was revealed through the capture of its embassy in Damascus , which was addressed to the Persian court .

The end of the covenant

In the same year in which Antipater put down the uprising of the Spartans in Europe, Alexander won the decisive victory over the Persian great king Dareios III in Asia in the Battle of Gaugamela (October 1, 331 BC). from that. Then he occupied successively until 330 BC The Persian royal cities Babylon , Susa , Persepolis and Ekbatana . Shortly afterwards the fleeing great king was murdered by his own followers around Bessos . Already in Persepolis, Alexander had set a beacon for the final victory of the Greeks after more than 150 years of fighting the Persian arch enemy by burning down the oldest Persian royal palace, which also marked the end of his vengeance campaign. Shortly afterwards, in Ekbatana, he finally released the federal troops, including the Thessalian regiments, from their military obligation and laden with booty for their homeland. But he himself did not intend to return, because at this point in time he had long been entitled to the successor to Darius III. raised in the rule over Asia ( see main article: Alexander Empire ), which he now wanted to enforce with his Macedonian warriors and Greek mercenaries.

Another long-term absence of the hegemon from Europe and an extension of Antipater's deputy became apparent, but the question of the further regulatory role of the Corinthian League was raised. Alexander did not give the returning federal troops any further instructions to the federal government or to Antipater, and the meeting of the Synhedrion on the occasion of the settlement of the mouse war in 330 BC continued. BC also his last known dar and until the death of Alexander and beyond that he was not called up anymore. There was no shortage of reasons to take action, as around 330 BC. The Aitolians conquered the island city of Oiniadai in breach of the peace and expelled its population, but neither the Synhedrion nor Antipater took steps in this matter. In fact, the Greek cities have not acted as a political union since then. The peace period of six years, which lasted until Alexander's death and was unusually long for Greek standards, was only able to guarantee hegemonic power. Apart from the Aitoler attack on Oiniadai, no other acts of war are known during this period, especially since there has been no power since the elimination of Persia and Sparta that could seriously challenge Macedonia.

The displeasure against Macedonia nevertheless persisted subliminally, if only in the person of Demosthenes, above all because the hegemon in particular had regularly violated the limits of the powers granted to him and thus fed resistance among the Greeks. As, for example, with the one before 331 BC. The Chairon was set up by Macedonia as a tyrant in Pellene , displacing the previously existing democratic order there, with which the hegemon had clearly broken the principle of internal autonomy. The discrepancies between the Allies and the Hegemon became apparent when Alexander 324 BC. Returned from India and Athens granted exile and even honorary citizenship to the fleeing treasurer Harpalos . Antipater immediately intervened and forced Harpalus to arrest; Demosthenes, involved in this affair, was banished from his city, but the leadership of the anti-Macedonian party was taken over by the no less determined Leosthenes . In Susa, Alexander also learned of the conquest of Oiniadai, which he now wanted to take care of personally, but which in turn turned the Aitolians against him.

Alexander led the final break with his in September 324 BC. He brought forth the exile decree issued by the later son-in-law of Aristotle , Nikanor , at the Olympic Games . This decree issued a pardon and the right of return for all those exiled from the Greek cities, the majority of whom were not only mercenaries, but also supporters of Promakedon parties, through which Alexander obviously wanted to gain political influence in the cities. In addition to the renewed violation of internal autonomy, the property and property guarantee stipulated in the federal treaty was de facto negated, since the returnees were to be restituted their previously confiscated property. Antipater was entrusted with overseeing the implementation of the decree, but each city had to regulate the modalities itself; the federal government itself was not even consulted by Alexander on this matter. In Athens, on the other hand, resistance formed around Leosthenes, as the exile decree also included the repatriation of the citizens of the island of Samos . These were 365 BC. Was driven out by the Athenians, who then populated the island with their own settlers ( clergy ). In the winter of 334 to 333 BC They had allowed the Persian fleet to stock up there in violation of the federal treaty. Athens was determined to defend Samos by force of arms, began its armor and made contact with the Aitolians, Lokrians and Phokers. As Curtius Rufus wrote, Athens was at the head of a new alliance directed against Macedonia, to which most of the cities of the Peloponnese and Thessaly later joined. Alexander, for his part, is said to have planned a siege of Athens because of the Sami, although this information is based on a dubious source.

The open battle between the Greeks and Alexander broke out because of his death in 323 BC. BC no longer, but this strengthened the determination of the Greeks additionally. But in the Lamic War that followed (323–322 BC) they were completely defeated by Antipater, who was supported by returning Macedonian veterans under Krateros . With their defeat, the Corinthian League now also came to an end de jure , because the victorious Antipater made no attempt to restore the federal constitution, but instead subjected the Greek cities to direct Macedonian control by installing occupations and the establishment of promakedonian regimes in the form of oligarchies or even tyrants, while at the same time eliminating democratic constitutions. The great enemy of the Macedonian Demosthenes then committed suicide. This Macedonian rule was actually more in keeping with the character of a personal rule by Antipater and his family than when he was in 319 BC. Died, the Macedonian governors in Greece did not remain loyal to his official successor, Polyperchon , but went almost completely over to Cassander , the son of Antipater.

Revival under Demetrios Poliorketes

In the Diadoch Wars that broke out after Alexander's death , the "freedom of the Greeks" was a much-quoted slogan that the warlords adopted in the hope of weakening Antipater and his family. First it was Perdiccas in the First Diadoch War (322-320 BC) to win the Greeks against Antipater, but his occupation troops and vassals held the cities firmly in his hands. The situation was similar in the Second Diadoch War (319–316 BC), when Polyperchon wanted to turn the cities against Kassander with a liberty decree, ultimately again unsuccessfully. Next, in the Third Diadoch War (316-311 BC), the powerful warlord Antigonos Monophthalmos took the lead in the heralds of Greek freedom and again called for a democratic uprising against Cassander. In the following years he sent several contingents of troops from Asia to Greece, which operated quite successfully there and liberated several cities. In the Diadoch peace of 311 BC The freedom of the Greeks was contractually agreed, but not realized. It was only during the fourth Diadoch war (308–301 BC) that Demetrios Poliorketes succeeded in 307 BC. The capture of Athens. There he eliminated the Promakedonian (Cassander-loyal) oligarchy under Demetrios von Phaleron and restored the democratic constitution. In the following years he was able to liberate almost all other Greek cities from the rule of Cassander.

Presumably on the advice of his father, Demetrios invited in 302 BC. The representatives of the Greek cities on the Isthmos of Corinth, probably back in the Poseidon sanctuary, in order to conclude a new covenant with them there. As in 337 BC BC almost all took part again; Exceptions were Sparta and Messenia in the Peloponnese and the Thessaly, who were firmly under Macedonian rule. In a fragmentary inscription from Epidaurus , the provisions of the new federal treaty are recorded, the content of which is based on those of 337 BC. Chr. Can be found. Accordingly, general peace ( koinē eirēnē ) was restored, Antigonos Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes recognized as hegemones and the latter also as military leaders ( strategōs autokratōr ). At the same time a war ( koinōs pōlemos ) against the common enemy Kassander was decided. The Federal Council ( synhedrion ) should meet four times a year for the Olympic , Delphic , Nemean and Istrian Games and be chaired by five chairmen ( prodedroi ), who should be appointed by the council itself in times of peace and by the hegemons in times of war. These guarantee the cities both tribute and garrison freedom. The council was again responsible for the referee function and the hegemon was responsible for the execution of the federal execution, whereby in the relationship between the two organs, as with the Philippine model, the hegemon assumed the role of 'de facto ruler' due to its military power. Moreover, the Greeks only recognized Antigonus and Demetrios as legitimate kings in the succession ( diadochē ) of Alexander and assured them that the hegemony would be hereditary.

Similar to its model, the revived covenant primarily served to legitimize its hegemon to rule over the Greek cities. The Macedonian family of the Antigonids , who had succeeded Alexander, used him primarily as a tool against their archenemy Cassander, who ruled Macedonia. Even though the Antigonids, in contrast to the Antipatrids , granted the Greek cities a much higher degree of internal freedom, they left no doubt that the Greeks had to orientate themselves externally towards their interests. Their covenant did not even last a year, however. As recently as 302 BC Demetrios went on the offensive and marched as far as Thessaly. But before the battle with Kassander broke out, his father called him and his armed forces to Asia to take part in the decisive battle against the Diadoch coalition, which they launched in 301 BC. Lost in the battle of Ipsos . In Greece the union collapsed instantly, in most cities the democrats were overthrown and the new oligarchic rulers switched to the side of Cassander. In Athens, the democrats under Olympiodoros were able to hold on for the time being, but now they refused to allow their former patron Demetrios Poliorketes to move into the city in a course of neutrality. When this 294 BC When he returned to Greece and captured Athens a second time, he did not restore the Corinthian Covenant.

It was only Antigonus III. Doson , the grandson of Demetrios, concluded in 244 BC. BC again a union between the Phokern, Boiotern, Euboiern and Lokrern, was chosen to their hegemon and renewed the dominance of Macedonia in Greece.

literature

The establishment and formation of the Corinthian Covenant (from 337 BC) is addressed in every scientific account of the time of Philip and Alexander, cf. the references in the corresponding articles.

- Hermann Bengtson : The State Treaties of Antiquity, Vol. II. The Treaties of the Greco-Roman World from 700 to 338 BC. Chr. , CH Beck, Munich 1962 ("StV II").

- Hermann Bengtson: The State Treaties of Antiquity, Vol. III. The treaties of the Greco-Roman world from 338 to 200 BC Chr. , Edited by Hatto H. Schmitt , CH Beck, Munich 1969 ("StV III").

- Albert Brian Bosworth: Conquest and Empire. The Reign of Alexander the Great . Cambridge Univ. Pr., Cambridge (1988) 1993, pp. 187ff., ISBN 0-521-40679-X . (On Alexander's relationship to the Bund.)

- Wilhelm Dittenberger : Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum , 3rd edition, 1915-1924 ("Sylloge³").

- Martin Jehne : Koine Eirene. Investigations into the pacification and stabilization efforts in the Greek polis world of the 4th century BC Chr. , Stuttgart 1994.

- Frank-Gernot Schuffert: Studies on war and power building in early Hellenism . Diss. Gießen 2005, p. 179ff., Here online .

- Peter Siewert and Luciana Aigner-Foresti (eds.): Federalism in Greek and Roman Antiquity , Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005.

- Marcus Niebuhr Tod : A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions , Vol. II, 1948 ("Tod II").

Secondary literature:

- William Scott Ferguson : Demetrios Poliorketes and the Hellenic League , In: Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens , Vol. 17 (1948), pp. 112-136.

- Klaus Rosen : The 'divine' Alexander, Athens and Samos , In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte , Vol. 27 (1978), pp. 20-39.

- S. Perlman: Greek Diplomatic Tradition and the Corinthian League of Philip of Macedon , In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte , Vol. 34 (1985), pp. 153-174.

- RH Simpson: Antigonus the One-Eyed and the Greeks , In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte , Vol. 8 (1959), pp. 385-409.

- Ralf Urban : The prohibition of domestic political upheavals by the Korinthischen Bund (338/37) in anti-Macedonian argumentation , In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte , Vol. 30 (1981), pp. 11-21.

Remarks

- ↑ Diodorus 16, 60, 4-5.

- ↑ The foundation date was the 16th Anthesterion (March 9th). Aischines , Gegen Ktesiphon (3), 95-98; Demosthenes , garland speech (18), 237; StV II, 343.

- ↑ Aischines, Against Ctesiphon (3), 141; StV II, 345.

- ↑ On the first federal meeting in Corinth at the beginning of the term of office of Archon Phrynichos (i.e. in the summer of 337 BC) see Diodor 16, 89, 1.

- ↑ Herodotus , Historien 7, 172-174.

- ↑ Diodorus 16:89, 2; Polybios 3, 6, 13; Cicero , De re publica 3:15 ; Arrian , Anabasis 2, 14, 4.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 1, 1, 2; Plutarch, Moralia 240a-b = Instituta Laconica 42; Justin 9, 5, 1-3.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Graecae II² 236b = Sylloge³ 260b = Death II, 177 = StV III, 403 Ib. See also Jehne, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Diodorus 16, 89, 3.

- ↑ Pseudo-Demosthenes 17, 8.

- ↑ Pseudo-Demosthenes 17, 19.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Graecae II² 236a = Sylloge³ 260a = Death II, 177 = StV III, 403 Ia.

- ^ German translation of the Corinthian Confederation's oath formula at AGiW.de according to E. Badian, Robert K. Sherk: Translated Documents of Greece and Rome , Vol. 2, Cambridge 1985, p. 123.

- ^ Justin 9: 5: 5-6.

- ↑ In the case of a dispute between Milos and Kimolos over three smaller islands, the Synhedrion had entrusted the city of Argos with making an arbitration judgment. Inscriptiones Graecae XII³ 1259 = Sylloge³ 261 = Death II, 179.

- ^ Sylloge³ 283 = death II, 192; Arrian, Anabasis 1, 16, 6. The Greek mercenaries fighting for Persia were exempt from the sanctions, which were aimed at the political sympathizers of Persia.

- ↑ Plutarch, Aratos 23, 4; Diodorus 17, 3, 3; Strabon 9, 4; 15. For a possible garrison in Chalcis see Polybios 28, 3, 3.

- ↑ Diodorus 16, 89, 3.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 3, 2; Plutarch, Demosthenes 23, 2, Phocion 16, 8-17, 1 and Alexander 11, 6; Marsyas , FGrHist. 135 F3.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 3, 3-5.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 4, 1-7.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 4, 9.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 1, 7, 3; Demades , The Twelve Years 17.

- ↑ Diodorus 17: 9, 5; Plutarch, Demosthenes 23, 1; Aeschines, Against Ctesiphon (3), 239.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 14, 2-4; Arrian, Anabasis 1, 9, 9; Plutarch, Alexander 34; Justin 11, 4.

- ↑ Diodorus 17:15 , 3; Arrian, Anabasis 1, 10, 6; Plutarch, Demosthenes 23, 6.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 17, 3-4.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 1, 16, 7. See Perseus Project : Flavii Arriani Anabasis Alexandri ed. By. AG Roos, Leipzig 1907. Translation from donations from Hellenistic rulers to Greek cities and sanctuaries , ed. by Klaus Bringmann; Hans von Steuben, Berlin 1995, p. 17. Furthermore, Plutarch, Alexander 16, 17-18.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 1, 18, 4-5 and 5, 19, 3-5.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 17, 5 and 118, 1.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 2, 15, 2; Curtius Rufus 3, 13, 15.

- ↑ The Corinthian Covenant had in 332 BC Through an embassy to Phenicia congratulated Alexander on his victory at Issus. Diodorus 17, 48, 6.

- ^ Diodorus 17, 63, 1; Aeschines, Gegen Ctesiphon (3), 136. Aeschines reproached Demosthenes in particular for failing to support Sparta.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 73, 5; Curtius Rufus 6, 1, 19.

- ↑ Aischines, Against Ctesiphon (3), 133; Diodorus 17, 73, 5-6; Curtius Rufus 6, 1, 20.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 2, 15, 2; Curtius Rufus 3, 13, 15.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 3, 11, 1-15 and 7, 19, 5; Curtius Rufus 4, 12, 1-16, 9; Plutarch, Alexander 33, 8-11. For the inscriptions of veterans from Orchomenos and Thespiai, who had dedicated part of their compensation to Zeus, see Death II, 197.

- ↑ Pseudo-Demosthenes 17, 10; Aeschines, Against Ctesiphon (3), 165.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 108, 4; Plutarch, Alexander 41; Athenaios 586d and 594b.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 108, 7-8; Plutarch, Demosthenes 25 and Moralia 846a.

- ↑ Diodorus 18, 8, 6; Plutarch, Alexander 49.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 5:12 ; Plutarch, Aristotle 11, 9.

- ↑ Diodorus 17, 109, 1 and 18, 8, 2-4; Plutarch, Moralia 221a. For inscriptions relating to the return of the exiles from Mytilene and Delphi for Tegea, see Tod II, 201–202.

- ↑ Diodorus 18, 9, 2-5.

- ^ Curtius Rufus 10, 2, 6; Diodorus 18, 10, 1-2.

- ↑ Athenaios 12, 538a – b = Ephippos , FGrHist. 125 F5.

- ↑ Diodorus 20, 102, 1; Plutarch, Demetrios 25, 3.

- ↑ Inscriptiones graecae IV² 1, 68 = StV III, 446th