Sadisdorf copper mine

| Sadisdorf copper mine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

| Mining technology | Ridge construction, ridge construction, bench construction | ||

| Rare minerals | Bismuth , bismuthinite , emplektite , sphalerite , galena | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | Josef Richard Sobitschka Edler von Wiesenhag, Sachsenz Bergwerks GmbH, VVB Buntmetall Freiberg | ||

| Start of operation | Periodic deposit from 1473 | ||

| End of operation | 1953 | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Tungsten, molybdenum, bismuth, tin, copper | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 50 ° 49 '37.6 " N , 13 ° 38' 47.2" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Sadisdorf | ||

| local community | Dippoldiswalde | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Saxon Switzerland-Eastern Ore Mountains | ||

| country | Free State of Saxony | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

The Sadisdorf copper mine is a mining area in the area of the towns of Sadisdorf , Hennersdorf and Niederpöbel in the Eastern Ore Mountains ( Saxony ). With several interruptions, tin, silver and copper were mined around Sadisdorf from 1473 to 1953. In the last operating periods, tungsten and molybdenum ores were also extracted. Successful exploration work on lithium was carried out in 2017/2018.

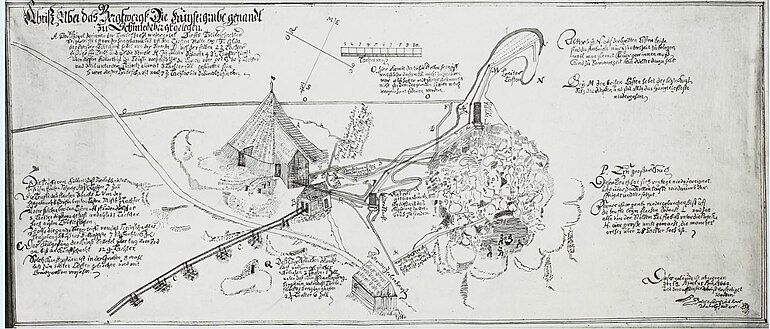

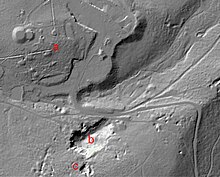

The actual “copper mine ” refers to the mine buildings and surface facilities in the area of the “Kupfergrübner Pinge” and the “Kupfergrübener Schacht”. Neighboring mining operations are the “Zinnklüfte” sub-area, the Perlschacht near Niederpöbel and the “Eule” mining area.

geology

Deposit structure

The Sadisdorf deposit is a combination of an impregnation ( Greisen ) and a gangue deposit with a complex structure.

The bedrock of the Sadisdorf ore deposit consists of biotite and muscovite gneiss with activated amphibolites . The Teplice rhyolite and foothills of the Sayda-Berggießhübler rhyolite dikes are embedded in it . There are also explosion breccias that penetrated the metamorphic rocks before the granite intrusions . These intrusions consist of the Sadisdorf granite , a three-phase intruded granite body, which is small or open in the area of the Sadisdorf pinge. The three-phase phase was initiated with a magma ascent from which a syenogranite (also known as “outer granite”) was formed. The second granite intrusion took place in the contact area between gneiss and syenogranite in the form of a 100 m thick monzogranite. The most recent intrusion event consists of albite granite (also known as "inner granite") that has aged in the upper area and represents the lying part of the deposit.

Furthermore, there is a pegmatite formation in the border area between the syeno and albite granite and the exclusive breccia, which is also known as “Stockscheider” or “quartz bell”. In addition, there are tubular, sulphide-mineralized intrusion breccias.

Mineralogy and Mineralization Types

The mineralogical-structural relationships of the ore bodies are as complicated as the geological-tectonic conditions. The old Sadisdorf external granite (considered here as an independent mineralization type) is a fine-grained rock, darkly colored by mica , made of quartz , topaz , fluorite and mica consists. The ore in the old ruins is mainly cassiterite , accompanied by a little wolframite as well as pyrite , chalcopyrite and solid bismuth. The medium-grained greisen of the inner granite also consists of quartz, topaz and mica with a little fluorite. It is mineralized with cassiterite, wolframite, dignified bismuth, hematite and pyrite, chalcopyrite, stannite (stannin), sphalerite , galena , bismuthinite and emplektite. The inner age including its pegmatitic edge facies ("quartz bell", "Stockscheider") has the highest scandium , niobium and tantalum content of all the Erzgebirge deposits. This part of the deposit consists of large crystalline quartz, a little mica and topaz as well as plenty of wolframite, which is partially converted into scheelite . Also worth mentioning is a quartz vein with an intense molybdenite mineralization.

The vein mineralization that is typical of the Erzgebirge ore deposits and is linked to tectonic fissures and fissures is the result of deposits of the tin-tungsten and quartz-polymetallic association. The tin veins are closely related to granite. The younger hydrothermal veins with sulphides, uraninite , fluorite, barite and, more rarely, BiCoNi Ag formations are distributed over the entire deposit. In the area of Niederpöbel further away from the granite, these hydrothermal tunnels predominate. The sulphide mineralization of the older, supercritical quartz-cassiterite veins has an indicator for tin, while this is absent in the younger hydrothermal veins of the quartz-polymetallic association.

The area around the vein mineralization also shows aging. Furthermore, ore veins have formed parallel to the rhyolite veins, which are to be regarded as transition types of the mineralization sequences described above. The mineralization of the intrusion breccias contains an enrichment of copper sulfides, so that in addition to tin and silver, copper was also extracted as a by-product, which led to the name "copper mine".

Tin, which has been the main extraction component for centuries, occurs mainly in the form of cassiterite and is found in the following types of aging and mineralization:

- Corridors and ruins in the endo- / exocontact area

- Floors in the endo / exo contact area

- mineralized domes and "seams" (storage corridors) in the endocontact area

- Breccias in the endo- / exocontact area

- in stratiform metasomatites in the exocontact area

Lithium that can be extracted in the future is bound to mica minerals (including zinnwaldite ). In the area of the aged syenogranite ("outer age"), a mostly vertical orientation of the mineralization parallel to fracture structures is assumed. The aged albite granite ("inner old men") is accompanied by a dome-shaped old age zone that contains higher proportions of lithium-containing mica. In principle, a zoning of mineralizations can be established for the Sadisdorf deposit , which can be differentiated in terms of tin, lithium and tungsten content but also on the basis of the general degree of fractionation of the respective petrographic units.

Furthermore, the mineralization contains the elements molybdenum, bismuth, tantalum, gold, scandium and zinc, albeit in a lower content.

history

Late Middle Ages to 1769

The beginnings of mining in the viewing area can be dated to the period between 1270 and 1280. There is no written evidence for this, but as a result of intensive mining archaeological investigations, this period can be assumed to be certain. The dating is based on a large number of dendrochronological analyzes on recovered pit timber, the number of which ensures sufficient statistical certainty. The reason for the investigations was the planned (and now largely implemented) construction of the Niederpöbel flood protection system. From a geological and geological point of view, their construction site is located on the southern edge of the Sadisdorf ore deposit. At some distance from the granitic intrusive bodies, the mineralization consists mainly of sulphidic veins with old man-like lateral impregnation of the host rock. In the embankment axis of the building, mining relics such as pingen , dumps , Meilerplatz etc. were known on both valley flanks . Thus, in execution of the Saxon Monument Protection Act, preparatory excavations as well as the archaeological support of custody and security work were initiated by the Saxon State Office for Archeology and carried out from 2010 to 2013. As a result of this work, a complex system of underground facilities such as tunnels, blind and day shafts, dies and side driveways over a length of 130 m could be verified and documented. In addition to the numerous wood finds mentioned above, toughness , clothing and ceramic fragments were also recovered. Whether the investigated area is the origin of the Sadisdorf mining industry must initially remain speculative. In any case, it seems plausible that the early miners opened up the deposit by means of horizontal excavations from the valley slopes rather than digging shafts in a laborious manner (these were later necessary for weather management). In addition, it was possible to trace and mine dikes into the interior of the deposit on the valley flanks. The simultaneous drainage of pit water down the valley was a welcome side effect. Whether it was prospecting or productive mining, or a combination of both, is still being debated.

On July 28, 1473 Melchior von Carlowitz was enfeoffed with all mines and soaps with the Naundorf manor. Iron, tin and copper were extracted. The mining in the copper mine "uff'n Green Forest" is on record from the year 1473rd After his death, his brother Friedrich von Carlowitz took over the manor. He is mentioned in an enfeoffment from September 18, 1476. In 1483, Hans Kölbel von Geising was named as the owner of the manor. In 1484 he was awarded the Sadisdorf mine by the Freiberg miner. His son and successor, Bartel Kölbel, received extensive mining privileges for 15 years from Duke Georg on February 11, 1502 . Under his son, Georg Kölbel, there was a constant dispute with the Glashütte mining authority over the mining rights in the manor. With the contract of September 8, 1557, which represents a vassal mining office order, Kölbel received all rights of the lower mountain shelf from Elector August . Copper ores were excluded because of their silver content. The most important pit was God's help pit . Step by step, the other mountain buildings Neue Gabe Gottes Fundgrube , Resurrection Christ Treasury , Beschert Glück Fundgrube , Bless Gottes Fundgrube and St. Georgen Fundgrube with Tiefen Erbstolln were consolidated.

In the pit buildings tin and copper ores were Weitungsbau by fire set won.

In 1607 Wilhelm von Schönberg , married to Anna Kölbel, took over the Naundorf manor with all mining rights. After his death, his widow had to sell the copper mine with all its accessories, smelters, tools, stamp mills and tin tithes due to inheritance disputes.

On January 22, 1622, a feudal letter for Heinrich von Bernstein , who was married to Anna Kölbel, was issued for the manor Naundorf with all rights . In 1626, a settlement was made with the former buyers to reverse the sale. In 1628 Günther von Bünau bought the manor and all rights from the Lauenstein line.

As a result of the expansion, constantly growing cavities were created in the body of the deposit. If these cavities reach a critical size, the surrounding rock can no longer absorb the loads that occur and the cavities break . In 1628, such a widening breach is said to have caused 31 deaths among the retired miners . As a result, there was massive water inflow and the pit sank .

In 1633 the Georgen or Mittelstollen were excavated to dissolve water . This is worth mentioning because during the Thirty Years War mining activities in the Ore Mountains generally declined. According to Balthasar Rösler , the St. Georgen Stolln had a depth of 25 laughs and the pits had reached a depth of 100 laughs.

Despite negative experiences, firing and expansion construction continued to be used for ore extraction , and further mine excavations occurred.

In 1636 the Pit Help of God dug its own shaft. So far she had promoted God's blessings through the pit . A horse peg was erected for extraction from a depth of 157 m . In addition, a 260 m long field rod was erected to lift the water up to the St. Georgen Stolln , which was driven by the water of the Saubach. Furthermore, there were two stamp mills for ore processing in the Saubach Valley .

Tin and copper ores were mined. Since the tithing was compulsory for the copper ores , the effort of mining and processing was avoided and these ores were left in the mine. This was noticed during an official inspection of the mines in 1647, and orders were given to mine and titrate these ores. So were z. B. 1651 applied 387.5 pounds (181 kg) copper and 15 solder (220 grams) silver.

In 1660 Günther von Bünau bought the Segen Gottes Treasure trove belonging to the Dresden merchant Georg Niere and united it with his mine for the blessing and help of God's copper mine . After the death of Bünau there was a lawsuit between Georg Niere and the heirs, in the course of which the mines were abandoned.

Mining was resumed in August 1670. A general inspection on August 14, 1677 certifies that the mining union was poorly managed. The reason for the general inspection was probably the death of two miners from steam when starting a fire. Obviously nothing was changed, because on May 2, 1679 there were two more deaths when the fire was started.

In the year 1684 there was a break in the daylight in the area of the former Pit Help of God . On April 23, 1686, the largest fracture occurred in the copper mine. The break occurred in the presence of a general inspection and continued to a depth of approx. 100 m and led to the formation of the Kupfergrübner Pinge. After finding rich tin ore in the area of the former Resurrection of Christ pit , a third Poch wash was built in the Pöbeltal. Despite good Erzanbrüche continued Zubuße demanded. Many trades gave up their kuxe . In 1694 Rudolf von Bünau took over the canceled Kuxe. In the same year, rich copper ores were broken into and a copper smelter was built, which was put into operation with two furnaces in 1696.

On September 1st, 1709 the filling point of the artificial and driving shaft broke. Thereupon a new, 40 Lachter deep shaft was sunk. At the urging of the Bünau brothers, the Freiberg miner Goldberg drove into the mine at the end of 1713. He recommended, despite good ore inroads, to stop overexploitation on the upper levels and excavate underground mines. In 1714 the depth of a new shaft was started and this was equipped with a horse peg. In the same year there was another daybreak . The St. Georg Stolln was also buried with broken masses. The installed artifacts were too weak to lift the water onto the upper adit.

By 1718 the largest excavation depth at that time was 200 m, which is why measures for pit drainage were necessary again. After 1726, the excavation of the Tiefen Kupfergrübner Stolln began at the confluence of the Sandbach and Saubach rivers . After the opening of bankruptcy proceedings over the assets of Rudolph von Bünau, the royal raft master Samuel Klemm acquired the manor for 22,100 thalers in a foreclosure sale in 1729 . Under Klemm the pit flourished again. The workforce was 71 men and there were 11 rap washes in operation. The highest copper output 1730 6342 kg and the highest tin 1732 8551 kg. Obviously, the complex ores were difficult to melt. Tin dishes, copper dishes (5-10 percent arsenic) and bell dishes (60 percent copper and 40 percent tin) were delivered to Dresden for processing. In 1739, the tunneling of the deep tunnel at 110 meters had to be abandoned after a rhyolite tunnel had been approached because of its extreme hardness. After Samuel Klemm's death in 1748, his son Johann Samuel Klemm succeeded him. After the collapse of the new main shaft, including drifting pegs and artifacts, Klemm gave up the pit in 1769. His recess debt was 12,800 thalers. He died that same year.

1769 to 1893

The Annisius family had owned the manor since 1769. In 1819, Christoph Anton Ferdinand von Carlowitz was named as a further owner. He is a direct descendant of Melchior von Carlowitz. In 1820, Christoph Anton Ferdinand von Carlowitz and his two nephews Albert von Carlowitz and Ernst Maximilian von Carlowitz appear as co-owners. In 1831 he transferred his share to the two brothers. From 1842 Albert was the sole owner.

In 1832 a union was founded. This began to overpower the Tiefen Stolln as Kupfergrübner Erbstolln . At 80 meters from the mouth hole , a NE-SW traversing corridor , the Lazy Morning Walk , was run over. The tunnel was opened further in the corridor. In 1838, at 460 meters from the mouth hole, people crossed the Unexpected Glück Morgengang . The drive was stopped for the time being and the mining of tin ore in the corridor started. In 1845 a Poch wash was built below Niederpöbel. In the meantime, driving in the tunnel on the Lazy Morning Walk had been resumed. At 540 meters you left the lazy morning corridor and crossed the path in the direction of Pinge. In 1846 the place stood at 582 meters. After 650 meters, the old drift shaft was cut through in 1851. The tunnel entered the mine building 42 meters below the St. Georg tunnel . The dismantling on the Unexpected Glück Morgengang had to be abandoned in 1851 after the passage had become cloudy .

In the meantime there were again differences with the Altenberger Bergamt. The Naundorf manor was only allowed to build on tin, but not on copper. After an objection from Carlowitz, who referred to the contract of 1557, he was granted mining rights for copper and other metals on August 30, 1843, limited to 20 years. In 1846 he sold the manor for 75,000 thalers to the economist Wilhelm Eduard Otto. On May 22, 1851, the "Law on Shelf Mining in the Kingdom of Saxony", which led to the abolition of the vassal mining offices, was passed. This law came into force on January 5, 1852. Otto gave up his rights on December 12, 1851.

Numerous routes were driven on the Kupfergrübner-Erbstolln-sole until 1853 and the ores mined. Here there were again the problems of separating the copper and tin ores that occur together. The parallel dike found in 1853 , a morning dike, led to a rich mineralization of tin with sulphidic ores. The ores could not be separated in the processing and the smelters did not accept the concentrate. Attempts to recycle an encountered molybdenum mineralization also failed. The plan was made to open up the deposit at depth, but was financially unable to do so.

One way out was to consolidate mining in the area. For this purpose, the Pöbler Mining Association was founded on March 22nd, 1854 . The mines of St. Michaelis including Himmelsfürst Fundgrube , Milde Hand Gottes Erbstolln , Kupfergrube Fundgrube , Owl Fundgrube including Hope to God Erbstolln , Zinnfang Erbstolln and Eichhorn Erbstolln were involved . At the time of the founding, however, Owl Fundgrube and Hope for God Erbstolln and Zinnfang Erbstolln were already set. Of the 128 Kuxes, only 64 Kuxes could be sold. After the foundation, the Eichhorn Erbstolln was discontinued. The St. Michaelis mine and the Himmelsfürst treasure trove were kept within deadlines.

In 1855 the red corridor , a morning corridor , was examined in the copper mine. This strokes southeast of the Pinge parallel to the Lazy Gang . In 1856, work at Kupfergrube Fundgrube and Milde Hand Gottes Erbstolln was stopped. A new central shaft was to be sunk to investigate the deposit.

On December 17, 1856, the depth of the shaft began. The shaft was named Perlschacht after the Altenberg miner Julius Friedrich Perl . Due to the high penalties, Kuxe continued to be canceled. In order to improve the financing of the project, the copper mine should be muted as a stock corporation. The Pöbler Mining Association leased them to an English entrepreneur who wanted to mine molybdenum and tungsten ores. However, this disappeared after a short time. After a chemical factory in Prague had expressed interest in the molybdenum ores, on December 28, 1859, the mine received an advance of 300 thalers from the "Fund for Extraordinary Needs in Mining" for fixture work for molybdenum extraction. The field of the Perlschacht was entered as a silver hope treasure trove and combined with the copper mine to form the silver hope and copper mine treasure trove . After the molybdenum ores had been mined, the mining association experienced a crisis in 1863. There was no pit board for the penniless club.

In 1867, the state took over 104 of the 128 kuxes into the Altenberger Bergbegnadigungsfonds. The pit was now carried on as a communication pit. The operation only took place in the Perlschacht area. Between 1868 and 1889 an additional fee of 175,150 marks was paid. 77 tons of ore were brought out for a profit of 38,540 marks. There was no mining in the copper mine. In 1889, however, 4.2 tons of molybdenum ores were accounted for, which were probably mined in the course of the closure of the mine. In May 1889 all work was stopped. On June 1, 1889, the shareholders' meeting decided to liquidate the company. The Niederpöbler mill owner FCE Krumpolt acquired all rights at a public auction. On April 1, 1893, the silver hope and copper mine were abandoned.

1903 to 1923

In April 1903 unsuspected Prague producer and imperial councilor Josef Richard Sobitschka Edler von Wiesenhag the area of the copper mine. The excavation of the Tiefen Stolln (Kupfergrübner Stolln) reached the mine area after 650 meters. In 1905 the St. Georgen Stolln was opened up as a second escape route. Until 1909, 155,457 marks had to be paid in penalties . The value of the ores sold during the same period was 141,204 marks. Tungsten and molybdenum were extracted, mainly from backfill ore in the mine. The workforce was 43 employees. In 1909 a processing facility was set up at the mine. Due to the good economic situation of the mine, after the debt was repaid between 1910 and 1913, a yield of 31,500 marks could be paid. In 1910 a smelter was built in Schmiedeberg to smelt the tungsten concentrate . In the pit, the Hungarian dogs were replaced by track-mounted dogs. In 1912 a processing plant was installed in the disused hut, but it was shut down again in 1913. Only the electromagnetic ore separation remained. With the beginning of the First World War , the workforce sank to 18 employees and the excavation of the mine fell to 50 percent of the pre-war value. The quadrupling of the tungsten price in 1915 benefited the mine, although the tungsten output fell from 13.7 t in 1914 to 5.3 t in 1915. From 1917, pneumatic hammer drills from Flottmann-Werke were used in the mine . From 1918, Berlin-based Kriegsmetall AG leased the mine. The number of employees rose to 54 and the mine was exploited for rapid ore extraction. The proceeds tripled in 1918. On April 30, 1919 the lease was canceled. With the end of the First World War, the prices for tungsten and molybdenum fell below the pre-war level. At the same time, the prices for equipment and machines rose sharply. The economic existence of the mine was no longer given. The owner withdrew from business life and moved to Vienna. In 1922 the operation was stopped and after the deadline on December 31, 1923 the mine fell into the open.

1935 to 1954

Since October 1935, the owner of the copper mine has been Miss M. Müller and comrades based in Aussig , operations began on February 15, 1936. In January 1937, the state of Saxony took over the mine. From August 1, 1937, the mine was taken over by the state-owned Sachsz Bergwerksgesellschaft mbH . The deposit was geologically examined, the stock situation was re-assessed up to the 115 m level and the mine buildings were prepared for extraction and extraction.

In 1937 the first 1,915 tons of ore were mined with 32 employees.

The digging of shaft 1 began as early as 1938. In September 1941, the preparatory work for the depth of shaft 2 began. In February 1942, the headframe was erected. In 1943 the construction of a processing plant began.

After the takeover of the Sachsenz Bergwerksgesellschaft mbH by the Sachsenz Bergwerks AG on April 1, 1944, the Sadisdorf operation belonged to the Altenberg operations department of the Sachsenz Bergwerks AG.

After the end of the Second World War , operations were stopped except for maintenance work.

On June 4, 1946, Order No. 23 was issued to the Deputy Chief of the SMA , Major General Dubrowski, to rebuild the mine and to resume production at the Sadisdorf copper mine. On August 1, 1946, the mine was formally subordinated to the newly established Industrial Administration 6. On July 1, 1948, the mine was subordinated to the VVB Buntmetall, which was founded on that day, as VEB Kupfergrube Sadisdorf . From 1949 the mining operation ran under the name VEB Zinnerz Sadisdorf.

In the operating period from 1947 to 1953, the geological and economic assessment of the old body was continued and the mining between the 30 m and 0 m levels began. At the same time, the construction of our own processing plant began.

After the events of June 17, 1953 , investments in heavy industry were restricted. As a result, all work in the deposit was stopped. Work has now been concentrated on the Altenberg deposit.

From the mid-1980s, the GDR's state geological service carried out a new exploration in the area of the 0 m and 30 m levels. The deposit was planned to replace the Altenberg deposit expiring in 2020. The mining should take place in the same way as Altenberg in Schubort operation and the ores should be transported over an approx. 11 km long cross passage to Altenberg and processed in the processing facility there. However, this work was stopped with the political upheaval in 1990.

The following table provides an overview of the quantities of tin ore and tin (if known) discharged.

| Operating period | Application in concentrate (t) | Mass of ore (t) |

|---|---|---|

| 1666-1769 | 75,388 (Greisen, copper ore) | |

| 1905-1921 | 39.7 molybdenum, 281.5 tungsten, 81.4 tin | |

| 1937-1941 | 27,929 (tin-tungsten ore) | |

| 1947-1953 | 12,653 tin | 47,548 (raw ore, dry) |

Present and perspective

In the course of rising raw material prices, the deposit became interesting again. On November 26, 2007, Tinco Exploration Inc., based in Vancouver, received a prospecting permit. In September 2008 she submitted an operational plan to the Saxon Mining Authority for the rehabilitation of the Kupfergrübner tunnel . In June 2011, the company returned the license.

In February 2013, the Saxon Mining Authority granted the mining law permit to Sachsenzinn GmbH Chemnitz to explore for tin, tungsten, copper, molybdenum, bismuth, tantalum, zinc, indium, gallium, germanium, gold, silver, cesium, rhenium, lithium and vanadium. This is a wholly owned subsidiary of Tin International Pty Ltd, based in Brisbane, which in turn is 60.33 percent owned by Deutsche Rohstoff AG .

In 2014, tin ore resources of 3.36 million tons with a tin content of 0.44 percent and a content of 15,000 tons of tin were identified according to the JORC standard. So far, resources of 12.2 million t with a tin content of 0.23 percent and a content of 28,000 t tin have been identified. In this case, the prime costs for extraction are € 38,000 / t tin. In the event of a possible dismantling, this will be done in the open pit.

On December 1, 2015, Sachsenzinn GmbH was converted into Tin International AG, based in Leipzig. Parent company Tin International Pty Ltd distributed its shares as dividend to shareholders and was liquidated in 2016. Deutsche Rohstoff AG took over 61.55 percent of the shares in Tin International. In 2015 the Kupfergrübner Stolln was cleared and made accessible. In May 2017 Tin International AG founded a joint venture with Lithium Australia based in Perth. The company has a processing process ("Si Leach") with which it is possible to remove lithium from the Sadisdorf ore or mineralization parageneses. In December 2017, 25 million tons of lithium raw material with a content of 47,000 tons of lithium were declared according to JORC. These results formed the basis for targeted drilling in the reservoir body at the end of 2017 / beginning of 2018, which confirmed the results of drilling and investigations from past decades. A resumption of mining activities on this basis in the short to medium term remains to be seen.

In June 2018, Tin International AG sold all licenses at the Sadisdorf and Hegelshöhe deposits to Lithium Australia and received a sale price of € 500,000 and five percent of the shares in Lithium Australia worth € 1,500,000. Lithium Australia transferred all rights to its wholly owned subsidiary, Trilithium Erzgebirge GmbH, which was founded on April 22, 2017 and is based in Munich.

Timetable

| Period | event |

| 1412 | First mention of the forge in Naundorf |

| around 1500 | First mention of numerous pits such as Help of God, Blessing of God, Resurrection of Christ, Beschert Glück Sankt Georgen, mining in the pumpkin / Löwenberger pits, owl, three brothers, Himmleiches Heer Erbstolln, Wenzelstolln, Wolfgang Christi, Drei Georgen, Steinhains Zeche, Dorothea and others |

| 1541-1666 | Mining in the pits Owl, Silver Cross, Holy Trinity, St. Christophs Zug, Hieronymus, St. Georgius, House of Saxony Erbstolln |

| 1544-1602 | Dismantling in the Windleithe treasure trove |

| 1561 | First mention of Hope to God Stolln |

| 1577 | Enfeoffment of the copper mine Milde hand Gottes |

| 1584 | Exposure of the Creuz treasure trove near Sadisdorf |

| 1587 | extensive dismantling in the owl treasure trove , excavation of the deep tunnel on the Pöbelbach |

| 1592 | Abandonment of the owl treasure trove |

| around 1600 | Tin mining in the pits Oberer St. Johannes, Mild Hand Gottes, Holy Trinity and others, first mention of the tin pits at Hohen Hau |

| 1608 | First mention of the mine Beschert Glück and the Erbstollns near Sadisdorf |

| 1615-1627 | First mention of the old Erzengler train on the Niederen Brandberg |

| 1618 | First mention of Zinnkluft mining near Niederpöbel |

| 1624-1641 | The Zinnkluft pits Help God, Engel, St. Barbara, Alte Zeche, Königin, Finken Flog and others in operation |

| 1638 | Sinking a mining shaft with God's help and several water loosening tunnels such as St. Georgen-Tolln . Greatest Output of the Pit Help of God |

| 1660 | Union of the pits God's blessings and God's help ; Mining standstill at a depth of 200 m |

| 1661 | Development of the tin mine brings luck , St. John and the Ascension of Christ |

| 1673 | Association of the pits brings luck , St. John and the Ascension of Christ |

| 1684 | Breaking day of 40 m on the pit God's help |

| 1686 | Break of 100 m on the Sadisdorf copper mine |

| 1696 | Construction of the Niederpöbel copper smelter |

| 1714 | Another break of day at the Sadisdorf copper mine |

| 1716 | First mention of the Oberer Löwe mine on Kirbsberg |

| 1728 | Ascension of the water loosening tunnel Prophet Samuel |

| 1730 | Up until then the most extensive copper mining in Sadisdorf, first mention of the Silberschurf treasure trove on Kirbsberg |

| 1738-1769 | Copper mining in the pits of God's gift, mean lion and God's new blessing |

| 1757-1803 | Drilling of the deep tunnel near Sadisdorf |

| 1767 | First mention of copper and lead mining in the area of the pits Unexpected luck and wise woman |

| 1772 | Closure of the pits at Niederen Brandberg and Hohen Hau |

| 1794-1805 | Active mining in the White Frau Erbstollen pits , unexpected luck and the discovery of the new luck morning walk |

| 1799 | Closure of the Windleithe treasure trove near Naundorf |

| 1805-1808 | Drilling of the Zinnfang Erbstollen near Niederpöbel |

| 1812 | The pits Güte Gottes , Neubeschert Glück and Erbstollen Hennersdorf west of the Zinnklifts in operation |

| 1833 | Dismantling on the owl treasure trove including silver hope and lion courage inheritance |

| 1841 | Extraction of fluorspar, barite and brown iron in the Eichhorn tunnel |

| 1835-1846 | Drilling of the Tiefen Pöbler main tunnel with two light holes |

| 1850-1851 | Opening of the deep silver hope tunnel |

| 1853 | Closing the Hope to God Stollen |

| 1854 | Cessation of mining at the Sadisdorf copper mine , the tin catching pits and in the Eichhorn tunnel |

| 1856 | Sinking of the Perl shaft and three associated gezeug lines |

| 1889 | Cessation of mining at the owl treasure trove |

| 1903-1954 | Resumption of mining in the Sadisdorf copper mine for bismuth, molybdenum and tungsten |

| 1945-1953 | Uranium mining in the area of the Perl shaft and around Niederpöbel by SDAG WISMUT |

| 1980s and 90s | Exploration work by the state geological service of the GDR |

| 2007-2013 | Revaluation of the deposit for lithium and metal raw materials, issue of exploration licenses by the Saxon Mining Authority |

| 2017/2018 | Exploration for lithium and metal raw materials |

Photos from the 1920s / 30s

Chew the "Pingenstollens" in Saubachtal 1929

Special features and things to know

- In 1879 the Swedish chemist Lars Frederik Nilson discovered the element scandium (Sc) in the mineral Kolbeckite , which came from the copper mine.

- The name "Kupfergrube Sadisdorf" is incorrect and misleading in two respects: Firstly, copper was never the main extraction component over the entire extraction period (see also the chapter on mineralogy and ore paragenesis ) and secondly, the mining facilities were not in the area of the Sadisdorf location, but on the Sadisdorf hallway. The only direct reference to mining in the village of Sadisdorf is the so-called "miners' settlement" on the eastern edge of the village, which was probably built in the 1930s / 40s in connection with the resumption of mining in National Socialist Germany .

- The ore extracted from the various pits was crushed in stamping works in the Saubach and Pöbeltal valleys and then further processed. The waste products of the stamp mills contained a high proportion of iron hydroxide (an accompanying component of ore paragenesis) and were discharged into the streams, the water of which then turned reddish. Since these streams of the Rote Weißeritz are tributary , their water also turned reddish. The river was then given the name "Rote Weißeritz", which is still in use today.

- Due to the remote location of the mine, mostly surrounded by forest, the pits were largely spared from dismantling as part of the Soviet reparation claims after the defeat of Germany in World War II .

literature

The following works and publications are cited in abbreviated form in the individual references:

| abbreviation | Full title |

|---|---|

| Meissner 1747 | Christoph Meißner: Cumbersome news from the Churfl. Saxon. Written Zien-Berg-Stadt Altenberg, located in Meissen on the Bohemian border, together with the associated diplomatic bus, and an appendix from the neighboring towns and Berg-Oertern , Dresden and Leipzig 1747 |

| Müller 1867 | Müller, CH: Geognostic conditions and history of mining in the area of Schmiedeberg, Niederpöbel, Naundorf and Sadisdorf in the Altenberger Bergamtsrevier , Freiberg 1867. |

| different authors | Yearbook for mining and metallurgy in the Kingdom of Saxony. 1873 to 1917 |

| different authors | Yearbook for mining and metallurgy in Saxony 1918 to 1934 |

| Wagenbreth, Wächtler 1990 | Wagenbreth, O .; Wächtler, E. (Ed.): Mining in the Erzgebirge - technical monuments and history , German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1990. |

| Baumann, Kuschka, Seifert 2001 | Baumann, L., Kuschka, E., Seifert, T .: Deposits of the Ore Mountains , Springer Spectrum 2001. |

| LfUGL 2008 | Revaluation of spar and ore deposits in the Free State of Saxony - profile catalog , Saxon State Ministry for Economics and Labor, Saxon State Office for Environment, Geology and Agriculture, Dresden, Freiberg 2008. |

| Thalheim 2009 | Thalheim, K., tin deposits of the Osterzgebirge, Zinnwald - Altenberg - Sadisdorf , in: EDGG - excursion guide of the German Society for Geosciences , Dresden 2009. |

| Schilka 2011 | Schilka, W .: The Sadisdorf copper mine . In: Erzgebirgische Heimatblätter , issue 3 2011, Kulturbund e. V., State Association of Saxony. |

| OBA 2013 | Mining in Saxony - Report by the Saxon Mining Office and the State Office for Environment, Agriculture and Geology (Raw Material Geology Department) for 2013. |

| Schröder 2014 | Schröder, F .: Medieval prospecting mining in the Pöbeltal near Schmiedeberg? In: Smolnik, R. (Ed.): ArchaeoMontan 2014, results and perspectives , proceedings for the international conference Dippoldiswalde 23-25. October 2014 (work and research reports on the preservation of monuments in Saxony, supplement 29) |

| SZ 12-2017 | Herz: Q .: Over 100,000 tons of lithium in Sadisdorf? , Saxon Newspaper , ed. 7th December 2017. |

| SZ 06-2018 | Herz, F .: Australians get big in Sadisdorf , Sächsische Zeitung, ed. June 11, 2018. |

| Ehser, Gruber 2018 | Ehser, A., Gruber, A .: From the "copper mine " to lithium-tin deposits , in: EDGG excursion guide and publications of the German Society for Geosciences: From tin to lithium - historical and new mining in the Eastern Ore Mountains , 44th meeting of the Working group mining consequences of the German Geological Society - Geological Association on 21./22. September 2018 in Dippoldiswalde, DGGV Heft 260, Berlin 2018. |

Remarks

Web links

- iDA environmental portal Saxony

- Saxon State Office for Environment, Geology and Agriculture

- State enterprise geobase information and surveying Saxony

- Saxon State and University Library, German Photo Library

- State Natural History Collections Dresden, Museum of Mineralogy and Geology

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c [Ehser, Gruber 2018, p. 89.]

- ↑ a b c [Baumann, Kuschka, Seifert 2001, pp. 137–139.]

- ↑ a b [Thalheim 2009, pp. 128–132.]

- ↑ a b c [Schilka 2011, pp. 17-18.]

- ↑ [LfUGL 2008]

- ↑ [Schröder 2014, pp. 215–223]

- ↑ a b c [Meißner 1747, pp. 449–455]

- ↑ Yearbook for the mining and metallurgical industry in the Kingdom of Saxony, year 1913, Freiberg 1913 pp. 22-24.

- ↑ [Schilka 2011, pp. 15-17.]

- ↑ a b [Wagenbreth, Wächtler 1990, pp. 185–187.]

- ↑ [OBA 2013, p. 11.]

- ↑ [SZ 12-2017]

- ↑ [SZ 06-2018]