Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof

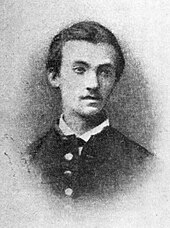

Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof [zaˈmɛnhɔf] (born as Eliezer Levi Samenhof ; German also Ludwig Lazarus Samenhof and Ludwig L. Zamenhof , Polish Ludwik Łazarz Zamenhof , Esperanto: Ludoviko Lazaro Zamenhof ; * December 3 July / December 15, 1859 greg. In Białystok ; † April 14, 1917 in Warsaw ) was a Polish ophthalmologist .

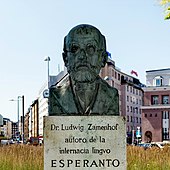

In 1887 he founded the planned language Esperanto under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto (German: Doktor Hoffender ) . His birthday is celebrated today by Esperanto speakers as Zamenhof Day.

Life

Zamenhof was born on Dec. 15, 1859 (after today, the Gregorian calendar ), the son of a Jewish family in what was then the Russian Empire belonging Polish born Białystok. Poles , Belarusians , some Germans and Jews who mostly spoke Yiddish lived in Białystok .

His father Markus (Yiddish Mordechaj ) was, like his grandfather, influenced by the Jewish Enlightenment movement Haskala and was specifically looking for a connection to European culture and the country in which he lived. Markus Zamenhof was an atheist and saw himself as a Russian. This differentiated him from his religious and Yiddish-speaking wife Rozalja. He worked as a language teacher for French and German , wrote teaching materials and temporarily ran a language school. Markus Zamenhof was a school inspector and censored publications for the Russian authorities. Eventually he received the title of Councilor of State .

The young Lejzer (later he added a non-Jewish-sounding first name to the practice of some Eastern Jews : Ludwik ) first attended the primary school in Białystok and, after his parents moved in 1874, the grammar school in Warsaw . He studied medicine , first in Moscow and later because of the growing anti-Semitism in Russia at the University of Warsaw , where he also received his doctorate . Later he specialized a. a. in Vienna on ophthalmology .

In 1887 he married Klara Silbernik (1863-1924), a factory owner's daughter whom he had met in Zionist circles during his student days. With her he had the three children Adam (1888-1940), Sofia (1889-1942) - the later wife of the Esperantist Wilhelm Molly - and Lidia (1904-1942). Lidia in particular soon became enthusiastic about Esperanto and taught and spread the language on her travels through Europe and America. All three children were murdered in the Holocaust . The engineer Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof (1925–2019) was his grandson.

For a long time Zamenhof had problems building an economic existence until he managed to earn a satisfactory income at the turn of the century. He was a practicing ophthalmologist until shortly before his death in 1917. Zamenhof himself suffered from heart and respiratory diseases. He was buried in the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery .

Zionism

Like his father, the young Zamenhof initially tended to assimilation, that is, to become a Jew in one of the European nations. He later wrote that he wanted to become a Russian writer as a child. But the pogroms of 1882 brought the young student to the early Zionist movement. So he founded a Zionist group in Warsaw and also worked out a Yiddish grammar.

Around 1885, however, he found that the goal of Zionism - a Jewish homeland in Palestine - was not realistic: the Hebrew language was dead, national sentiment among the Jews was misjudged by Zionism, and in general Palestine was too small for all Judaism. It could take in two million Jews at most, and the rest of the masses stayed outside.

Instead, he saw the future of the Jews more secure in a world in which linguistic, cultural and religious barriers were bridged or completely dismantled. That led him back to the internationalist ideas.

When a Jewish Esperanto association was to be founded in 1914, Zamenhof replied negatively: Every nationalism brings bad things, so it would serve its unhappy people best if it strived for absolute justice among the people.

Esperanto

Zamenhof was already interested in foreign languages as a child . The father's preferred language was Russian , his mother's Yiddish , and he must have learned Polish on the street . He got to know German and French at an early age, then Greek , Latin and English at school . He must also have a good command of Hebrew , from which he later translated the Old Testament into Esperanto.

From an early age he dreamed of a new, easy-to-learn language that could provide a neutral instrument for divided humanity. His first attempt was the Lingwe Uniwersale, now only fragmentary , in which he and his friends sang a song on his 18th birthday in 1878. From the further development process fragments from the status 1881/82 have been preserved, which were also published later.

Around 1885 Zamenhof had finished his final draft, which he published in various languages in 1887, first in Russian on July 26th. The German title was: "International Language", and that was the name of the language. Since Zamenhof feared for his reputation as a doctor, he gave the forty-page brochure under the code name Dr. Esperanto out. ( Esperanto literally means one who hopes ). However, this pseudonym soon established itself as a synonym for the language itself.

As a result, Zamenhof managed - in contrast to other authors of a new language - to publish a magazine ( La Esperantisto ) and annual address books. Since the Volapük of the German clergyman Johann Martin Schleyer was at its height of success at about the same time, Esperanto did not have it easy, and the rapid decline of Volapük, which had fallen victim to disputes among its followers, made it even more difficult. At that time, the idea arose that a planned language would automatically break down into dialects .

Around 1900 Esperanto gained a foothold in Western Europe after the Russian Empire and Sweden . By the First World War , local groups and regional associations were founded by Esperantists on all inhabited continents. This freed Zamenhof from personal responsibility for his language, which had finally become independent of him.

"Human doctrine"

Zamenhof was also fascinated by another idea, namely to promote not only a neutral language, but also a neutral worldview . He first published his ideas as Hillelism (1906), named after a pre-Christian Jewish scholar named Hillel , later under the Esperanto name Homaranismo . Translated this means something like "doctrine of humanity".

The doctrine of humanity was a commitment to international understanding and religious tolerance based on common principles. So people should believe in a higher being together and otherwise keep their religious customs. And in countries with different languages, all of these should be equally official languages , with Esperanto acting as a bridging language .

However, the complicated details of the multicultural society - which is exactly what Zamenhof's doctrine of humanity is about - remained unsolved. Even among Esperanto speakers, the teaching, which most people perceive as general humanism and to which they have nothing to object to, does not play an essential role.

Last years of life and afterlife

Zamenhof experienced the outbreak of war in Cologne in 1914 , on the way from Warsaw to Paris for the 10th Esperanto World Congress. After a difficult detour via Scandinavia , he didn't get home until weeks later. In the last years of his life, which were affected by a heart disease, Zamenhof intensified his work on the Esperanto translation of the Bible and wrote a memorandum to the diplomats who should think about the rights of minorities during the peace negotiations. During the war, when Warsaw had already been occupied by Germany , Esperanto fans such as the Swiss Edmond Privat visited him . When Zamenhof died at the age of 57 on April 14, 1917, a large crowd accompanied the funeral procession to the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street . There were not only Esperanto speakers, but also many of Zamenhof's poor Jewish patients.

He was remembered as a modest, somewhat shy man, very idealistic and pleasant to deal with. Only later did research show that Zamenhof was also sober and deliberate and cleverly avoided being instrumentalized by parts of the supporters against others. His statements on language are still one of the foundations of the Esperanto Academy today .

Streets, squares and other objects named after Zamenhof or Esperanto

In Bad Kissingen , the Esperanto Square next to the guest house at Bismarckstraße 22, where Zamenhof first stayed for a cure in 1911 , has been remembering him since 1991 . In Berlin-Neukölln, where the Esperantist Wilhelm Wittbrodt worked , Esperantoplatz is also dedicated to Zamenhof, on the 75th anniversary of his death in 1992 the Zamenhof oak was planted on the square in front of which Neukölln's Mayor Bodo Manegold unveiled a commemorative plaque in 1999 . The Zamenhofpark in Berlin-Lichtenberg was inaugurated in July 2009 on the occasion of the Esperanto World Congress in Białystok in the year of Zamenhof's 150th birthday. In 2017, a square in Herzberg am Harz was named after the Esperanto inventor on the 100th anniversary of his death.

There is also Zamenhofstrasse in Warsaw in his honor . In the German-speaking world, streets in Dresden , Linz , Mannheim , Rüsselsheim am Main , Schwelm , Stuttgart and Wuppertal bear his name .

The asteroid (1462) Zamenhof , discovered in 1938, was named after him. Two years earlier, his life's work had already been the inspiration for the naming of the asteroid (1421) Esperanto .

Zamenhof in literature

The GDR writer Hermann Kant (1926–2016) deals in the novel “The Stay” (1977) with different views of Zamenhof and his Esperanto. In a conversation in the destroyed Warsaw ghetto, a Polish officer asks the arrested German skeptically: “What do you mean: If you had been able to Esperanto, and the people in Milastrasse and Zamenhofstrasse would also have been able to Esperanto, what do you think they would have understood each other can that one will not sink Zamenhofstrasse ...? "

The Munich writer Dagmar Leupold (born 1955) has the mute historian Johannes explain in her novel "Green Angel, Blue Land" (2007): "I should write a biography of Zamenhof ... - There is no German-language available account of his life and work." Zamenhof is portrayed in a pictorial and emotional way, "who would not have acted out of academic ambition or scientific pragmatism, but out of sheer despair, out of productive despair always infused with hope," with the aim: "Abolish the differences that provide the pretexts for all systems of oppression "

The writer Johano Strasser (born 1939), whose first novel “The Sound of Fanfare” (1987) has to do with his family history, Esperanto and Zamenhof, tells of his in his autobiography “When we were still gods in May” (2007) Esperanto parents and Ludwig Zamenhof as the “house saint” of his childhood and youth, whose thinking he met again in the PEN Club and fascinated him: “the old dream of the one humanity, of the dignity that all people, regardless of race and culture, to come ... ".

The writer Richard Schulz (1906–1997) tells the life of Zamenshof in “The miraculous life of poor Doctor Lazarus” (1982).

Zamenhof family

The brothers and children of Zamenhof also learned Esperanto. After his death, his son Adam was invited to Esperanto congresses as a guest of honor. The daughter Lidia was active in spreading Esperanto and the Baha'i faith and was also pacifist. Many of Zamenhof's descendants and relatives did not survive the Second World War and especially the Holocaust : Adam Zamenhof was murdered as early as 1940; Lidia and the third child Zofia allegedly died in Treblinka in 1942.

After the war, Adam's wife Wanda Zamenhof continued the spiritual legacy. After her death in 1954, her son Louis Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof (the grandson of the language founder; died in 2019) was the surviving “representative” of the Zamenhof family. By profession an engineer , he lived in since 1959 France . He was a frequent guest at congresses, but played no official role in the language community.

Works (selection)

- International language . Preface and full textbook. Warsaw 1887 (as "Doktoro Esperanto"; first edition; online ).

- Hamleto . Warsaw 1894 (as translator; 5th edition. Paris 1929).

- Esenco kaj estonteco de la ideo de lingvo internacia . Yekaterinburg 1994 (first edition: 1900).

- Fundamenta krestomatio de la lingvo Esperanto . 18th edition. Rotterdam 1992 (first edition: 1903, as editor).

- Fundamento de Esperanto . 11th edition. Pisa 2007 (first edition: 1905).

- Proverbaro Esperanta . 3. Edition. La Laguna 1974 (first edition: 1910).

- La Sankta Biblio Malnova kaj Nova Testamentoj tradukitaj el la originalaj lingvoj . Londono: Brita kaj Alilanda Biblia Societo Edinburgo kaj: Nacia Biblia Societo de Skotland 1978, ISBN 978-0-564-00138-5 .

- Lingvaj respondoj . 6th edition. Vienna 1995 (first edition: Paris 1927).

- Biblio . Dobřichovice CZ 2006 (as a translator; translation from the Old Testament 1907–1914).

- Aleksandr Korzhenkov (Ed.): Mi estas homo . Kaliningrad 2006.

- Brief communication on the international language Esperanto . Edition Iltis, Schliengen 2001, ISBN 3-932807-17-0 (reprint of the Nuremberg edition 1896 - with an afterword by Reinhard Haupenthal ).

- Johannes Dietterle (Ed.): Originala Verkaro . Hirt & Son, Leipzig 1929.

literature

- Markus Krajewski: Globalization projects: language, services, knowledge . In: Niels Werber u. a. (Ed.): First World War. Cultural studies manual . Stuttgart / Weimar 2014, pp. 51–84.

- Marjorie Boulton : Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto . London 1960 (English).

- René Centassi, Henri Masson: L'homme qui a défié Babel . Ramsay, 1995.

- Ziko van Dijk: Esperanto. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 2: Co-Ha. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02502-9 , pp. 262-265.

- Ziko van Dijk: World language from Warsaw. LL Zamenhof, Esperanto and Eastern Europe . In: Eastern Europe . Number 4, 2007, p. 143-156 .

- Ludovikito [Ito Kanzi]: Senlegenda biografio de LL Zamenhof . Tokyo 1982.

- Andreas Künzli: LL Zamenhof (1859–1917) Esperanto, Hillelism (Homaranism) and the “Jewish question” in Eastern and Western Europe . Wiesbaden 2010.

- Naftali Zvi Maimon: La kaŝita vivo de Zamenhof. Originalaj studoj . Tokyo 1978.

- Ulrich Matthias: ZAMENHOF, Ludwig Lazarus. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 20, Bautz, Nordhausen 2002, ISBN 3-88309-091-3 , Sp. 1590-1592.

- Edmond Privat : Life of Zamenhof . Inventor of Esperanto 1859-1917. Ed .: Ulrich Lins . 6th edition. UEA, Rotterdam 2007, ISBN 978-92-9017-097-6 (Original title: Vivo de Zamenhof . Translated by Ralph Elliott).

- Roman Dobrzyński : The Zamenhofstrasse. Written after discussions with Dr. LC Zaleski-Zamenhof. agenda, Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-89688-485-5 (Original title: LA ZAMENHOF-STRATO . Translated by Michael J. Scherm).

Web links

- Literature by and about Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature on Ludwig L. Zamenhof in the ONB's collection for planned languages

- Bibliography of publications by and about Ludwig Zamenhof on Litdok East Central Europe / Herder Institute (Marburg)

Individual evidence

- ^ Edmond private: Vivo de Zamenhof. 6th edition, ed. by Ulrich Lins, UEA, Rotterdam 2007, pp. 19-25; Ziko Marcus Sikosek: Esperanto sen mitoj. 2nd Edition. Antwerp 2003, pp. 298-302.

- ^ Edmond private: Vivo de Zamenhof. 6th edition. edited by Ulrich Lins, UEA: Rotterdam 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Klara Zamenhof died. In: Prager Tagblatt , XLIX. Volume, No. 291/1924, December 13, 1924, p. 5, bottom left. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ Wendy Heller: Lidia. The Life of Lidia Zamenhof, daughter of Esperanto . Oxford: George Ronald Oksfordo, 1985.

- ↑ Chuck Mays: Obituary: Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof on esperantic.org of November 26, 2019.

- ^ Leon Zamenhof: El la Biografio de D-ro L.-L. Zamenhof. In: Esperanto. June 20, 1912, pp. 168-170.

- ^ Jean Luc Tortel: Zamenhof kaj medicino. In: Sennacieca Revuo. 133 (2005), supplement to the Sennaciulo. No. 9, 2005 (1203), pp. 9-21.

- ↑ Marcus Sikosek: The neutral language. A political history of the Esperanto World Federation. Bydgoszcz 2006, pp. 35/36.

- ^ Naftali Zvi Maimon: La kaŝita vivo de Zamenhof. Originalaj studoj. Tokyo 1978, pp. 106/107.

- ^ After: Edmond Privat: Vivo de Zamenhof. 6th edition. edited by Ulrich Lins, UEA, Rotterdam 2007, pp. 133/134.

- ↑ Ziko Marcus Sikosek: Esperanto sen mitoj. 2nd Edition. Antwerp 2003, pp. 296/297.

- ↑ Gaston Waringhien: Lingvo kaj vivo. Rotterdam 1989 (1959).

- ↑ July 14th according to the Russian calendar. This date is widely believed to be the date of approval from the censors to distribute the printed book. Possibly. 21 would be more correct, cf. Albault ( Memento from May 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Wojciech Usakiewicz: Esperantist world views . Berlin 1995, pp. 3-8.

- ↑ Marcus Sikosek: The neutral language. A political history of the Esperanto World Federation. Bydgoszcz 2006, pp. 37/38; Ziko van Dijk: World language from Warsaw. L. L. Zamenhof, Esperanto and Eastern Europe. In: Eastern Europe. 2007/04, pp. 143–156, here 150–152.

- ^ Edmond private: Vivo de Zamenhof. 6th edition. edited by Ulrich Lins, UEA: Rotterdam 2007, p. 132.

- ↑ LL Zamenhof: La Sankta Biblio: Malnova kaj Nova Testamentoj tradukitaj el la originalaj lingvoj. Brita kaj Alilanda Biblio Societo, Londono; Nacia Biblia Societo de Skotlando, Edinburgo kaj Glagovo 1926/1988, ISBN 0-564-00138-4 .

- ^ Ludoviko Lazaro Zamenhof: Post la Granda Milito. In: The British Esperantist. Volume 10, March 1915, pp. 51-55.

- ↑ About Gaston Waringhien: Leteroj de Zamenhof. 2 volumes, Paris 1948.

- ^ Fritz Wollenberg: The Esperantoplatz in Neukölln. Redesign - meetings - exhibitions - summer festivals! In: Esperanto. Language and culture in Berlin and Brandenburg. 111 years, Jubilea LIbro 1903-2014. Mondial, New York / Berlin 2017, pp. 439–444.

- ^ Fritz Wollenberg: Berlin has a Zamenhof Park (2009). In: Esperanto. Language and culture in Berlin and Brandenburg. 111 years, Jubilea LIbro 1903-2014. Mondial, New York / Berlin 2017, pp. 444–450.

- ↑ Herzberg names Platz after the Esperanto inventor on April 8, 2017 on ndr.de

- ↑ Hermann Kant: The stay. Novel. Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1986, pp. 367-368.

- ↑ Dagmar Leupold: Green Angel, Blue Land. Novel. CH Beck, Munich 2007, pp. 16-20.

- ↑ Johano Strasser: When we were still gods in May - memories. Pendo Verlag, Munich and Zurich 2007, pp. 34 and 279.

- ↑ Richard Schulz: The wondrous life of poor Doctor Lazarus. Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation Stuttgart e. V., Stuttgart 1982.

- ↑ Kürschner's German Literature Calendar 1984. Werner Schuder (Ed.), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, p. 1112.

- ↑ Zofia Banet-Fornalowa: La familio Zamenhof: Originala biografia studo. Cooperativo de Literatura Foiro, La Chaux-de-Fonds 2001.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zamenhof, Ludwik Lejzer |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Samenhof, Ludwik Lejzer; Samenhof, Ludwig Lazarus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian ophthalmologist and philologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 15, 1859 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Białystok |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 14, 1917 |

| Place of death | Warsaw |