Nanking massacre

The Nanking massacres ( Chinese 南京 大 屠殺 / 南京 大 屠杀 , Pinyin Nánjīng dàtúshā ; Japanese 南京 大 虐殺 Nankin daigyakusatsu ) were war crimes committed by the Japanese occupiers in the Chinese capital Nanking (or Nanjing ) during the Second Sino-Japanese War . According to the protocols of the Tokyo trials , over 200,000 civilians and prisoners of war were murdered and around 20,000 women and girls raped , according to other estimates .

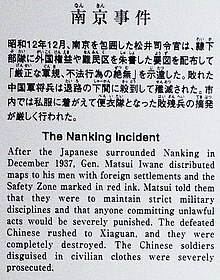

The massacres began on December 13, 1937 after the city was occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army and lasted six to seven weeks.

background

Japan intensified its colonialist aspirations in the 1930s . The Mukden incident provoked by the Kwantung Army in 1931 served as a pretext for the occupation of Manchuria . Because of the Chinese civil war , there was little resistance, and Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo to administer the occupied territories .

China resisted Japan with a trade boycott and refused to unload Japanese ships. As a result, Japanese exports fell to a sixth, which fueled sentiment in Japan. In particular, one incident in which five Japanese monks were beaten up in Shanghai in 1932 (one monk later succumbed to his injuries) was picked up by the Japanese media to stir up anger among the Japanese people. On January 29, 1932, Japanese marines and sailors attacked the Chinese parts of the city. Japan captured the city in the First Battle for Shanghai . Estimates speak of around 18,000 Chinese people killed and 240,000 homeless . China was then forced to lift the trade boycott; a demilitarized zone was established around Shanghai. In May 1933 an armistice was signed.

On July 7, 1937, there was an incident at the Marco Polo Bridge , in which Japanese and Chinese soldiers engaged in firefights. The Second Sino-Japanese War began . The Japanese army expected a quick victory as China was still at war, but the second battle for Shanghai lasted unexpectedly long and resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. Around 200,000 Japanese soldiers fought a far higher number of Chinese soldiers in a bitter house-to-house war . Japan was only able to win the battle in mid-November, when the Japanese 10th Army landed in Hangzhou Bay and the Chinese troops were threatened with encirclement .

In his directive of August 5, 1937, Emperor Hirohito explicitly issued the order not to adhere to the Hague Agreement when treating Chinese prisoners of war . The Japanese Empire, which had never signed the Geneva Convention , took almost no prisoners in China. Chinese soldiers who tried to surrender were usually shot or killed after capture. At the end of the war, the Japanese army had only 56 Chinese prisoners of war under its control.

Road to Nanking and occupation of the city

On the way to Nanking, Japanese troops massacred Chinese prisoners of war. According to Japanese reporters, because of the rapid advance for Japanese soldiers, there were no restrictions on the part of their officers, which also resulted in numerous rapes and looting.

When the Japanese army approached Nanking, most of the foreigners fled the city along with numerous residents. Foreigners who stayed in the city set up the “International Committee for the Nanking Security Zone”, the aim of which was to create a security zone for civilians. The committee consisted largely of business people and missionaries; Its chairman was the German businessman John Rabe , since the Nazi regime had signed bilateral agreements with Japan such as the Anti-Comintern Pact .

On December 1, 1937, Mayor Ma Chaochun ordered civilians to go to the security zone. He fled the city on December 7th and the international committee took de facto control of the civilian population.

Japanese troops reached Nanking around December 8, 1937 and enclosed the city. They dropped leaflets urging the defenders to surrender the city. When there was no reaction, the battle for Nanking broke out . The Japanese bombed Nanking several times and thus wore down the morale of the Chinese troops . At 5 p.m. on December 12, 1937, the Chinese city commander ordered the retreat, which had not been planned and was extremely disorderly: the soldiers stripped of their weapons and uniforms and in some cases attacked civilians in order to obtain civilian clothing. Panic also gripped parts of the population who fled with the soldiers to the Yangtze . However, there were hardly any ferries or boats available for transport. In the panic attempts to board the remaining means of transport, many people drowned in the cold river.

On December 13, 1937, Japanese troops occupied Nanking.

Operations

The exact events and the number of victims are still controversial today. In addition to massive looting and pillaging the reports speak of arbitrary mass executions . After the end of the war, Chen Guanyu, head of a judicial commission of inquiry at Nanking Court, summarized survivors' testimonies collected by the Red Cross and other charities.

“According to their statements, the marauding Japanese soldiers cut off women's breasts, nailed children to walls or roasted them over an open fire. They forced fathers to rape their own daughters [,] and castrated Chinese men. They skinned prisoners alive and hung Chinese by their tongues. "

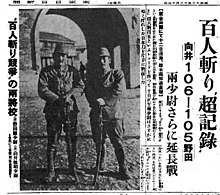

The competition between two Japanese officers, which of them would be the first to kill 100 people with the sword ( Hyakunin-giri Kyōsō ) , gained particular fame . The Tokyo newspaper Tōkyō Nichi Nichi Shimbun reported on the competition like a sporting event, with daily updates on who was in the lead. On a home leave in Japan, Noda said at a performance in front of a class at a primary school that he had hardly killed any men in combat, but almost exclusively killed prisoners of war. A student later (1971) remembered his words.

“I only killed four or five fighting with the sword…. When we had taken a position, we told them: Come on, come on, come here. The Chinese soldiers were stupid enough to get out of their positions one by one. We let them line up and struck them down one after the other. "

After the Japanese defeat, both officers were sentenced to death as war criminals and executed . Some historians believe that the officers killed fewer than a hundred people each and that the numbers they cited were exaggerations. Bob Wakabayashi, professor at York University in Toronto, interprets the event as a journalistic staging; the way the press has dealt with the issue has been the subject of much debate in Japan since 1967.

There was also mass rape of women and children. Many of these rapes took place in a systematized process, with soldiers going from house to house looking for women and girls. Often the women were killed immediately afterwards, which was often associated with great atrocities. The rapes were often carried out in groups and some women were abducted.

A Japanese war veteran testified:

"It was customary to put a bottle in the vagina of a young woman after she was raped by the group and then kill the woman by breaking the bottle inside her."

Eyewitness report Xia Ruirong:

“One day they dragged a very pretty woman in there, about 20 years old. Twelve soldiers took her to an empty room in the basement, harassed her with suggestive remarks, tore her clothes off and raped her. From five in the morning to six in the evening. "

The type of killings in the city and its surroundings varied. Civilians (including children and toddlers) and prisoners of war were bayonet stabbed, shot, beheaded , drowned and buried alive by the thousands . The Japanese naval veteran Mitani Sho later reported that the army had a trumpet signal, which meant that the Chinese were fleeing and they were to be killed.

Units of soldiers marched through the city and its surroundings, executing Chinese prisoners of war and indiscriminately killing men and boys suspected of having fought for the Chinese army. Children, old people and whole families were murdered for the smallest of reasons.

Documented mass executions took place at the same time. 10,000 civilians and prisoners of war were taken out of the city under the pretext of transfer to a camp and were killed with machine guns near the Jiangdong Gate . Several months later, burial groups buried over ten thousand bodies in two large trenches. 1,300 prisoners of war and civilians were rounded up at the Taiping Gate, where they were blown up with landmines , and the survivors were then doused with kerosene and set on fire or killed with bayonets. In and around the city, groups of hundreds of Chinese prisoners of war, often mixed with civilians, were killed with machine guns and explosives, and smaller groups were killed with bayonets and swords and some were buried alive.

The commander of the sixteenth division Nakajima Kesago wrote in his diary on December 13:

“We see prisoners everywhere, so many that there is no way to deal with them. The general guideline is 'do not take prisoners'. That meant that we had to take care of them with all the trimmings. They came in hordes, in units of thousands or five thousand, we couldn't even disarm them ... I later heard that the Sasaki unit (the Thirteenth Brigade) alone eliminated about 1500; a company commander guarding the Taiping Gate 'looked after' another 1,300. Another 7,000 to 8,000 collected at Xianho Gate surrender. We need a really big ditch to handle those 7000 to 8000, but we can't find one; so someone suggested the following plan: 'Divide them into groups of 100 to 200 and we will lure them to a suitable place to finish them off'. "

Former Japanese soldier Tadokoro Kozo later wrote in his book:

“At that time, the company I belonged to was stationed in Xiaguan. We used barbed wire to tie the captured Chinese into bundles of ten [,] and tied them to racks. Then we poured gasoline on them and burned them alive ... I felt like we were killing pigs. "

Kawano Hiroki was a Japanese military photographer at the time:

“I've seen all kinds of horrific scenes… headless corpses of children lying on the floor. They forced prisoners to dig a hole and kneel in front of it before they were beheaded. Some soldiers were so skillful that they took over this business in a way of severing the head completely, but leaving it hanging from a thin piece of skin on the torso so that the weight pulled the body down into the ditch. "

General Matsui Iwane , commander in chief of the Japanese troops, was unable to take part in the conquest of the city due to his illness with tuberculosis . After realizing the atrocities that had taken place in the city, he condemned the events, stating, among other things: "My men have done something that is absolutely wrong and extremely unfortunate." He was killed during the Tokyo trials for the in Nanjing indicted and found guilty of war crimes and hanged on December 23, 1948 .

reaction

News barely leaked out of Nanking due to censorship and the lack of independent reporters. But especially the International Committee for the Security of Nanking tried to inform the western world of the events. After the German businessman John Rabe was withdrawn from Siemens in Nanking in February 1938 and returned to Germany, he gave several lectures about the massacre and contacted Chancellor Adolf Hitler . He was then briefly arrested by the Gestapo . In April 2009 the film John Rabe , which deals with this topic , was shown in German-speaking countries .

In addition to the Panay incident , reports of the Japanese atrocities caused a shift in relations between Japan and the United States . This led to the US imposing a trade embargo on Japan and later intervening in the war with a volunteer squadron, the Flying Tigers . The trade embargo in particular is now seen as the reason for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor .

Today's rating

The extent of the massacre is still controversial today. In the Japanese war crimes trials , there was talk of "more than 200,000 victims". This number of victims was justified in the verdict on the basis of statements by survivors and taking into account Nanjing's population statistics. Gen.-Lt. Tani Hisao ( 谷寿夫 ; 1882–1948) was indicted in March 1947 as the main person responsible for the massacre before the Chinese Nanjing Military Tribunal for the Trial of War Criminals (not to be confused with the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which met in Tokyo ) and after a month Sentenced to death trial.

Observations by Japanese soldiers, reports by reporters and Chinese and Western residents of Nanking during the massacre (all of which were only able to provide rough estimates), and records of funerals (in which there are no differences between Chinese and Japanese, soldiers and civilians) are the basis for the significantly different number of victims differentiated) and different views on which area and which period should be assigned to the event. At the same time, massacres were carried out in Zhenjiang, 84 kilometers away, and in Hsuchow, a hundred kilometers away , the victims of which were included in the Chinese calculations. The Chinese government estimates over 300,000 fatalities; In his report on the massacre of Adolf Hitler, John Rabe wrote that, according to Chinese reports, 100,000 Chinese civilians had been murdered, but the Europeans remaining in Nanking only assumed 50,000 to 60,000 fatalities. In nationalist circles in Japan, the number of victims is estimated to be much lower. A joint research group of high-ranking historians set up by both countries has not yet been able to reach an agreement on this question, although the Japanese side ultimately avoided going into this point of discussion.

During a visit to the Nanjing Memorial Hall on May 4, 2004, the then general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party , President Hu Jintao , expressed the view that the massacre, which should never be forgotten, was aimed at the patriotic education of the youth.

The question of why the massacre went unnoticed for many years in the historical process is answered differently:

- The American writer Iris Chang argues that after the successful communist revolution in China in 1949 , both China - the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China in Taiwan - tried to win Japan over for reasons of political recognition and economic relations. Because they didn't want to snub Tokyo, they dropped the subject of Nanking for a long time. Nor did the United States press Japan to come to terms with the Nanking atrocities. Washington needed Tokyo as an ally against the Soviet Union and against Red China.

- The Chinese scholar Tang Meiru gives a different explanation. It was not until China regained strength in the 1970s and 1980s that China's self-confidence was raised to such an extent that it could now face past humiliations and deal with the role of victim.

In the Chinese public, the massacre determines the attitude towards Japan to a considerable extent. A study published in August 2005, carried out with the collaboration of the University of Tokyo, found that most Chinese people first mentioned the Nanking massacre in connection with Japan. In the same month, the evaluation of the events in Nanking in Japanese textbooks gave rise to protests in China: On April 9, 2005, riots broke out against Japanese institutions because the Japanese government had approved textbooks that described the massacre as an "incident".

The Japanese public has had a heated debate since the 1970s. Initially, revisionists from the nationalist camp denied the massacre, calling the reports about it Chinese propaganda . However, they lost their credibility after it was discovered that one of their leading representatives, the historian Tanaka Shōmei , had massively falsified and altered information. Records from the Japanese army and eyewitness reports from Japanese soldiers also proved beyond doubt that monstrous atrocities had taken place in Nanking. These reports are now considered accurate in Japan.

gallery

The massacre in literature

Honda Katsuichi published his first book on the subject of the Nanking massacre in 1972 (title: 中国 の 旅 Chūgoku no tabi , "China trip"). The high-circulation newspaper Asahi Shimbun had printed excerpts from the book a year earlier. The section on the massacre sparked a great deal of public attention at the time. Numerous books on the subject have appeared in Japan since the 1970s, with very different tendencies. For a long time the western world showed little interest. This changed in 1997 with the publication of the book The Rape of Nanking - The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II (German: The rape of Nanking. ) By the Chinese-born American Iris Chang . The book also tells the story of John Rabe ; Chang compares him to Oskar Schindler .

See also

- War crimes committed by the Japanese armed forces in World War II

- List of Japanese massacres in China

- Khabarovsk war crimes trials

- Manila massacre , about 100,000 victims

literature

Japan

- Katsuichi Honda: The Nanjing Massacre. A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame. ME Sharpe, Armonk NY 1998, ISBN 0-7656-0335-7 .

- Tadao Takemoto, Yasuo Ohara: The Alleged "Nanking Massacre" - Japan's rebuttal to China's forged claims. Meiseisha, Tokyo 2000, ISBN 4-944219-05-9 .

west

- Iris Chang : The Nanking Rape. The massacre in the Chinese capital on the eve of World War II. Pendo, Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-85842-345-9 .

- Erwin Wickert (Ed.): John Rabe. The good German from Nanking . Rabe's diaries. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-421-05098-8 .

- Mo Hayder : Tokyo. Goldmann, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-442-31018-0 . (Roman, German)

- Mo Hayder: Tokyo. Bantam, London / New York 2004, ISBN 0-593-04970-5 . (English original)

- Ha Jin : Nanking Requiem. Ullstein, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-550-08890-2 .

- Ishida Yuji: The Nanking Massacre and the Japanese Public. In: Christoph Cornelißen , Lutz Klinkhammer , Wolfgang Schwentker (eds.): Cultures of memory. Germany, Italy and Japan since 1945. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-596-15219-4 , pp. 233–242.

- Gerhard Krebs: Nanking 1937/38. Or: dealing with massacres. In: News of the Society for Nature and Ethnology of East Asia. Hamburg 167-170.2000-2001, ISSN 0016-9080 , pp. 299-346.

- Uwe Makino: Nanking massacre 1937/38. Japanese war crimes between denial and oversubscription. With an introduction by Gebhard Hielscher. Norderstedt 2007, ISBN 978-3-8370-0469-4 .

- Daqing Yang: The Challenges of the Nanjing Massacre. Reflections on Historical Inquiry. In: Joshua A. Fogel (Ed.): The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography. University of California Press, Berkeley 2000, ISBN 0-520-22006-4 , pp. 133-179.

- Wieland Wagner: Collective bloodlust. 70 years of Nanjing. In: Der Spiegel. 50/2007, ISSN 0038-7452 , p. 124ff.

- Huang Huiying: John Rabe - A Biography. Foreign Language Literature Publishing House, Beijing 2014, ISBN 978-7-119-08737-5 .

Movies

- 1995: Black Sun: The Nanking Massacre in the Internet Movie Database (English) - Director: Tun Fei Mou

- 2007: Nanking - Directed by Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman

- 2009: John Rabe - Director: Oscar winner Florian Gallenberger

- 2009: City of Life and Death - Directed by Lu Chuan

- 2009: The Children of the Silk Road - Director: Roger Spottiswoode

- 2011: The Flowers of War - Directed by Yimou Zhang

Web links

- Japanese Imperialism and the Massacre in Nanjing - by Gao Xingzu, Wu Shimin, Hu Yungong, & Cha Ruizhen (English)

- Etude sur le négationnisme japonais et les massacres de Nankin (French)

- The Nanking Atrocities - Comprehensive reports of massacres in Nanking (English)

- Memorial Hall of the Victims in the Nanjing Massacre (1937–1938) (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Levene, Mark and Roberts, Penny: The Massacre in History . 1999, p. 223, 224 .

- ^ Totten, Samuel: Dictionary of Genocide . 2008, p. 298, 299 .

- ↑ Berthold Seewald: Nanking 1937: They forced fathers to rape their daughters . December 13, 2017 ( welt.de [accessed June 20, 2019]).

- ^ Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East: IMTFE Judgment . Paragraph 2, p. 1012.

- ↑ Fujiwara Akira: Nitchū Sensō ni Okeru Horyo Gyakusatsu. Kikan Sensō Sekinin Kenkyū 9, 1995, p. 22.

- ^ Herbert Bix: Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Duckworth, London 2001, ISBN 0-7156-3077-6 .

- ^ Joseph Cummins: The World's Bloodiest History. Fairwinds Press, Beverly 2009, ISBN 978-1-59233-402-5 , p. 149.

- ↑ Katsuichi Honda, Frank Gibney: The Nanjing massacre: a Japanese journalist confronts Japan's national shame. ME Sharpe, Armonk 1999, ISBN 0-7656-0334-9 , pp. 39-41.

- ^ “ Only from August 15 to October 15, 1937, Japanese aircraft attacked Nanjing over 65 times, among which over 90 aircraft were employed at one time. ”(Memorial Hall of the Victims in the Nanjing Massacre)

- ^ A b Joseph Chapel: Denial of the Holocaust and the Rape of Nanking. 2004.

- ↑ a b c Nora Sausmikat: The Third World in World War II. Our victims don't count - Japan's war of annihilation against China. Research international (ed.). Association A, Hamburg 2005, pp. 225-231.

- ^ Tōkyō Nichi Nichi, December 13, 1937.

- ^ A b Trial of the Nanking Atrocitie. In: nankingatrocities.net. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015 ; accessed on April 4, 2018 .

- ↑ compare Uwe Makino: Nanking Massaker 1937/38. Japanese war crimes between denial and oversubscription. BoD Norderstedt, 2007, p. 105ff.

- ^ Bob Tadashi: The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt Amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971-75. In: Journal of Japanese Studies. Vol. 26, No. 2, The Society for Japanese Studies, 2000, p. 307.

- ↑ Widespread Incidents of Rape In: Japanese Imperialism and the Massacre in Nanjing. Chapter X.

- ↑ A Debt of Blood: An Eyewitness Account of the Barbarous Acts of the Japanese Invaders in Nanjing. In: Dagong Daily, Wuhan edition. February 7, 1938.

- ^ Military Commission of the Kuomintang, Political Department: A True Record of the Atrocities Committed by the Invading Japanese Army. July 1938.

- ↑ What happened at Ginling College, where around 20,000 women and children had fled, was documented in particular. The Japanese abducted over a hundred women, but brought them back after days of raping. Some of these women died as a result of their abuse (see: Erwin Wickert (ed.): John Rabe. Der gute Deutsche von Nanking. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-421-05098-8 , p. 147– 149).

- ^ A b John E. Woods: The Good man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe. Random House, New York 1998, ISBN 0-375-40211-X , p. 281.

- ↑ a b c d Celia Yang: The Memorial Hall for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre: Rhetoric in the Face of Tragedy. ( Memento from June 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 318 kB) 2006.

- ↑ a b Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura: Japan's Last Vets of Nanking Massacre open up. On: google.com/hostednews/afp May 15, 2010.

- ^ Documents on the Rape of Nanking, 254.

- ↑ On February 5, 2009, the Japanese Supreme Court sentenced Higashinakano Shudo and Tendensha Publishing House to pay 4 million yen in damages to Shuqin Xia, who said she was the "7-8 year old girl" in Magee's film. Contrary to what he said in his book, Higashinakano was unable to prove that Shuqin Xia and the girl were different people and that she was therefore not an eyewitness to the nanking massacre, Chinese hail Nanjing massacre witness' libel suite victory in People's Daily Online, Author on Nanjing loses libel appeal in The Japan Times Online

- ↑ Celia Yang: The Memorial Hall for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre: Rhetoric in the Face of Tragedy. ( Memento of June 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 318 kB) 2006. The author refers to: James Yin: The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs. Innovative Publishing Group, Chicago 1996, ISBN 0-9632231-5-1 , p. 103.

- ↑ Nanjing remembers massacre victims. on: news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ a b Akira Fujiwara: The Nanking Atrocity: An Interpretive Overview. on: japanfocus.org October 23, 2007.

- ↑ quoted from Iris Chang, see literature, p. 52.

- ^ Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East: IMTFE Judgment . Paragraph 2, p. 1015.

- ↑ Chapter China. In: Philip Piccigallo: The Japanese on Trial. Austin 1979, ISBN 0-292-78033-8 .

- ↑ Joshua A. Fogel (Ed.): The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography. University of California Press 2000, p. 49.

- ↑ China Weekly Review , October 22, 1938, ZDB -ID 433449-8

- ↑ quoted from Iris Chang, see literature, p. 253, footnote 100; although she mentions restrictively that Rabe did not make a systematic census.

- ↑ The Japanese side avoided getting deeper into the debate over the number of victims in the incident, which is the biggest point of contention over the incident between scholars from the two countries. ( Memento from June 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Daily Yomiuri Online. February 2, 2010.

- ^ "This is a good place to carry out patriotic education. We must never forget the patriotic education of the young and this tragic history must also never be forgotten ”. Memorial plaque, The Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders.

- ↑ Iris Chang, see Literature, p. 11.

- ↑ Quoted from: Joshua A. Fogel (Ed.): The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography. University of California Press, 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Edward J. Drea: Review of Katsuichi, Honda, The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame . H-Japan, H-Net Reviews, November 1999 ( online )

- ↑ The Rape of Nanking. Pendo, 1999, ISBN 3-85842-345-9 .